For the last two weeks, I have been, well, geeking out as cicadas have begun appearing in my heavily wooded neighborhood in Charlottesville. I’ve seen two waves of the little beasties emerge from beneath the shrubs outside my cottage, and each time, have immediately documented my sightings online. Social-networking and online-news sources this spring alerted me to two websites that are calling on “Citizen Scientists” to document the emergence, one hosted by Radio Lab and the other by National Geographic.

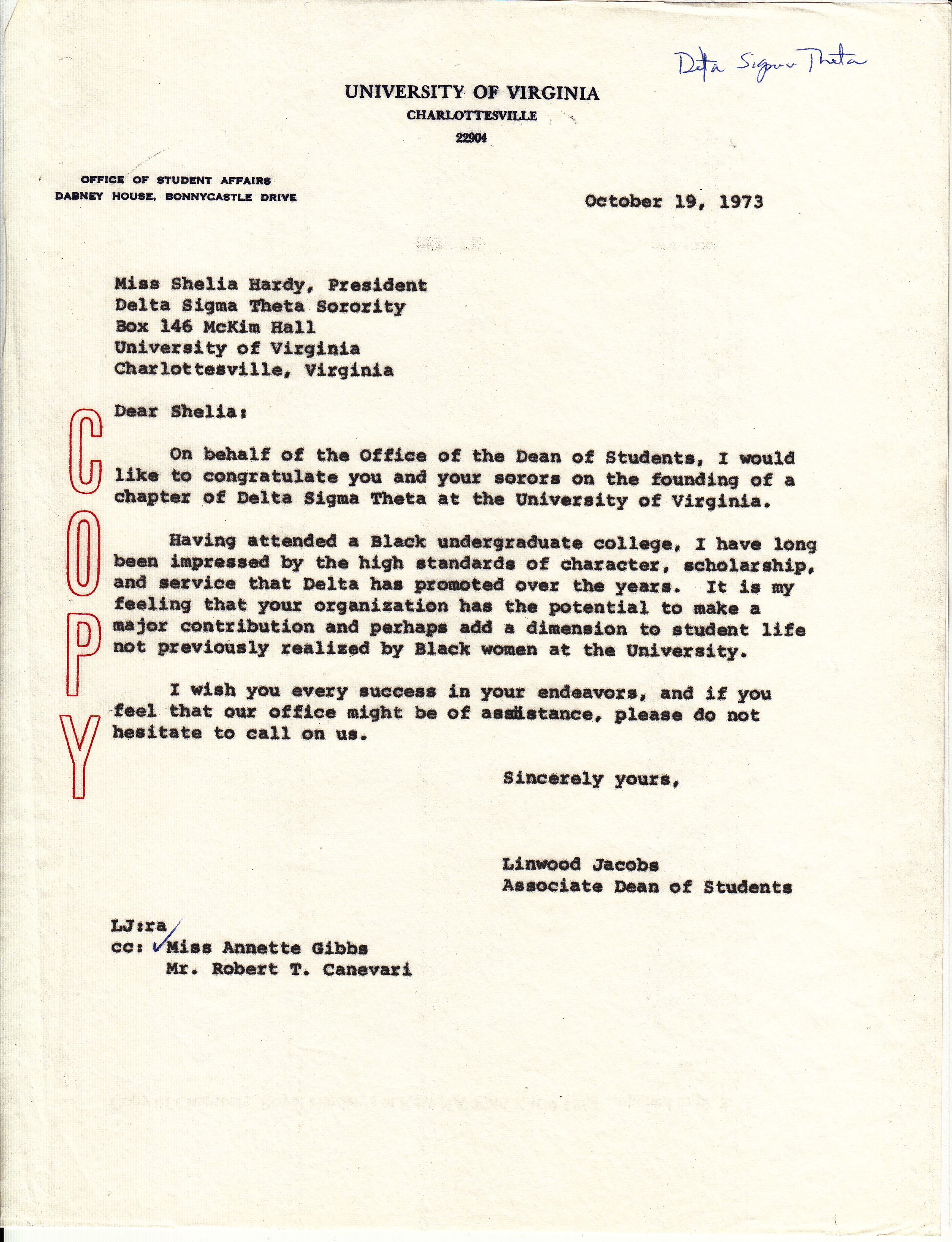

One of the first cicadas to emerge in my neighborhood in Charlottesville, May 15, 2013. It rests on the branch of an Abelia shrub, under which may be seen numerous circular holes from which this and other cicadas emerged. (Photo by Molly Schwartzburg)

Why the big deal? Brood II cicadas (Magicicada septendecim) spend seventeen years living underground before emerging to sing loudly, lay eggs, and then die within about a month. Because of this unusually lengthy life cycle, Brood II cicadas are relatively mysterious to scientists, and a lot of basic questions about their activities remain unanswered. So scientists have been taking advantage of crowdsourcing opportunities to gather information; emergences are spotty (some people will see no cicadas in their yards) and range across hundreds of miles. Projects like the ones I’m participating in will perhaps provide enough data to keep the lab rats busy for, oh, maybe another seventeen years.

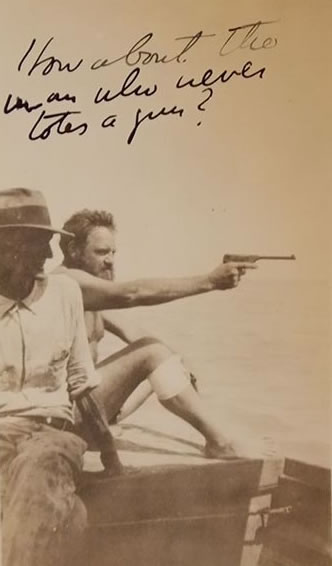

I wondered how earlier Virginians experienced cicada emergences, and was thrilled to discover that Special Collections holds a remarkable 200-year-old personal account of a fellow magicicada enthusiast, who wrote his own history of “locusts,” as they were commonly termed in that period. “J. S.” (who felt uncomfortable giving his/her full name to “such a rough draft”) tracked what are now known as Brood II and Brood X, which also emerges every 17 years, and will emerge next in 2021. J. S. explains how careful observation led him to determine that the cicadas feed off the roots of trees while underground (correct!). He also describes with great detail the workings of the female’s “perforator” (now called the “ovipositor”), the mechanism with which she lays her eggs.

J. S.’s 4-page long description of emergences in 1766, 1783, 1800, and 1809 is reproduced here in full, each page first in transcription (with paragraph breaks added and some spelling and punctuation modified for ease of reading), followed by an image of the page. Enjoy!

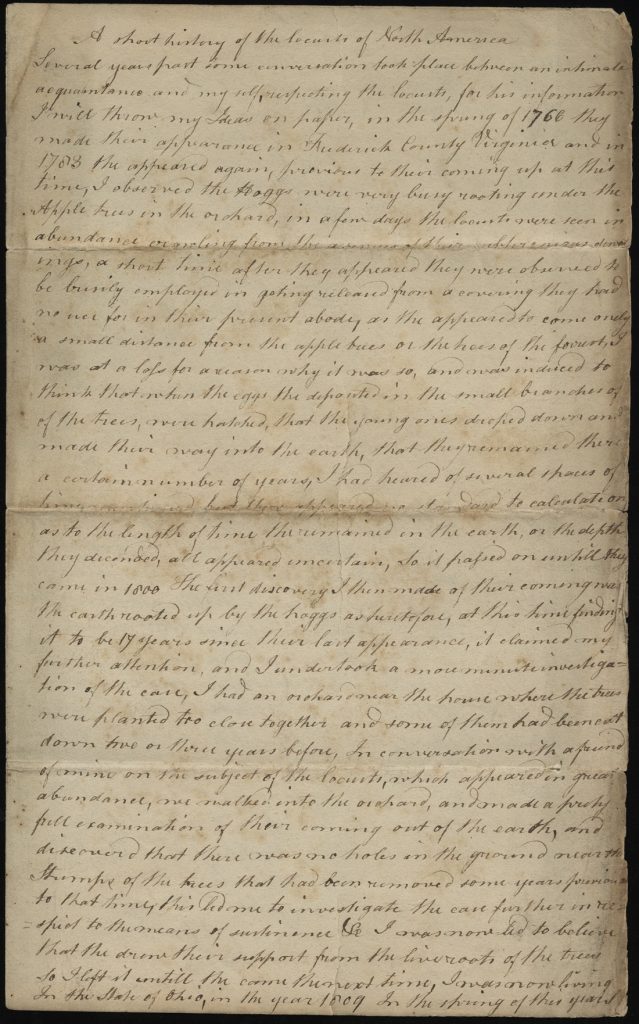

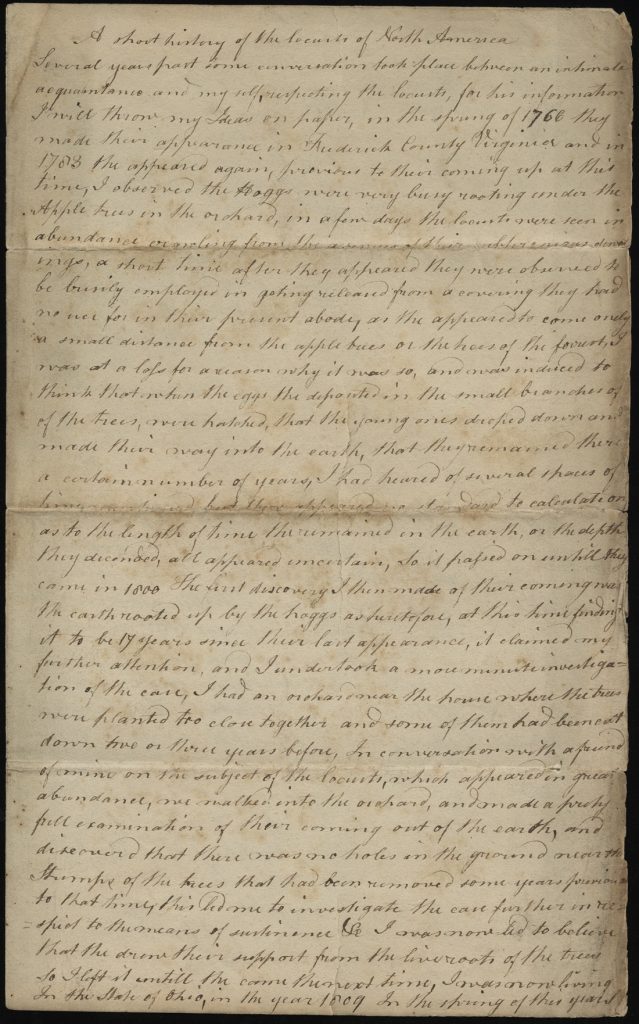

A short history of the locusts of North America

Several years past some conversation took place between an intimate acquaintance and my self, respecting the locusts. For his information I will throw my Ideas on paper. In the spring of 1766 they made their appearance in Frederick County Virginia and in 1783 the appeared again. Previous to their coming up at this time, I observed the Hoggs were very busy rooting under the Apple trees in the orchard. In a few days the locusts were seen in abundance crawling from the avenues of their subterenious dwellings. A short time after they appeared they were observed to be busily employed in geting released from a covering they had no use for in their present abode. As they appeared to come onely a small distance from the apple trees or the trees of the forrest, I was at a loss for a reason why it was so, and was induced to think that when the eggs they deposited in the small branches of of the trees, were hatched, that the young ones droped down and made their way into the earth, that they remained there a certain number of years. I had heared of several spaces of time mentioned, but there appeared no standard to calculation as to the length of time they remained in the earth, or the depth they decended. All appeared uncertain.

So it passed on untill they came in 1800. The first discovery I then made of their coming was the earth rooted up by the hoggs as heretofore. At this time finding it to be 17 years since their last appearance, it claimed my further attention, and I undertook a more minute investigation of the case. I had an orchard near the house where the trees were planted too close together and some of them had been cut down two or three years before. In conversation with a friend of mine on the subject of the locusts, which appeared in great abundance, we walked into the orchard, and made a prety full examination of their coming out of the earth, and discovered that there was no holes in the ground near the stumps of the trees that had been removed some years previous to that time. This led me to investigate the case further in respect to the means of sustenance & I was now led to believe that they drew their support from the live roots of the trees So I left it until they came the next time.

I was now living In the State of Ohio in the year 1809. In the spring of this year I

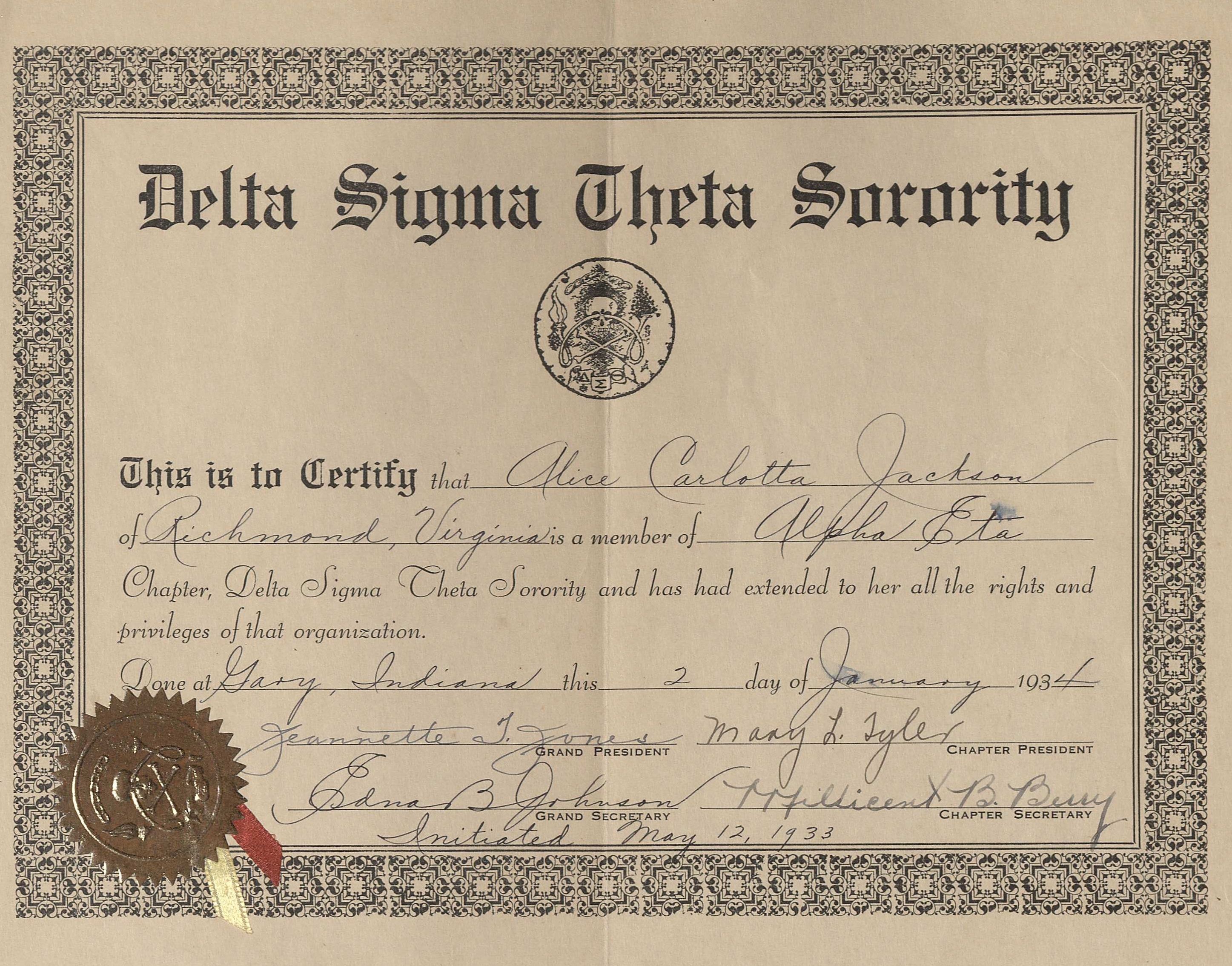

First page of A Short History of the Locusts of North America (MSS 9727). (Digitized by Molly Schwartzburg)

I was fencing a garden. I observed in diging the post holes at one corner of the garden, we found many locusts near the Surface, but in the other part we did not discover any. Here the former observation took place. There was the green roots of a shade tree that we had removed, and the locusts were not found further than the roots had spread. This was several years before the time that I expected they would again shew themselves, according to my former calculations, yet I judged we should have another locust year before the time in course. I now made enquiry of some of the former setler that had lived near me, when the locusts had made their appearance last, but none of them appared clear as to the time. And recuring back to the time that I discovered that they did not come up round the dead appletree Stumps, it struck me that it was similar to our not finding any locusts in the holes we dug for the post holes of our garden fence.

This spring the locust came in great abundance. A further examination took place. I took a walk in order to satisfy my curiosity, and after advancing some distance and passing several stumps of trees that had been cut not more than two or three years, and could not find one hole where the locusts had come up, and proceeding on a little further, I discovered one hole, and then another, and casting my eye a little further on, I observed several holes the locusts had made nearly in a straight line. In order to gratify my curiosity a little more, I got a spade and dug till I found the root of an elm tree that was now exactly under the row of holes, the locusts had made, and searching further about the roots of the elm, I discovered there was small open spaces round the roots, where I thought it was at least probable, the locusts had lain and sucked the sap out of the roots. Here they could not have decended more than four or five feet , as the leavel of the creek was not more than that distance.

The knowledge I thought I had gained of their history led me to pry minutely into the manner of their increas. I found that they hatched in a short time after the eggs were deposited in the small branches of the trees, and that they were

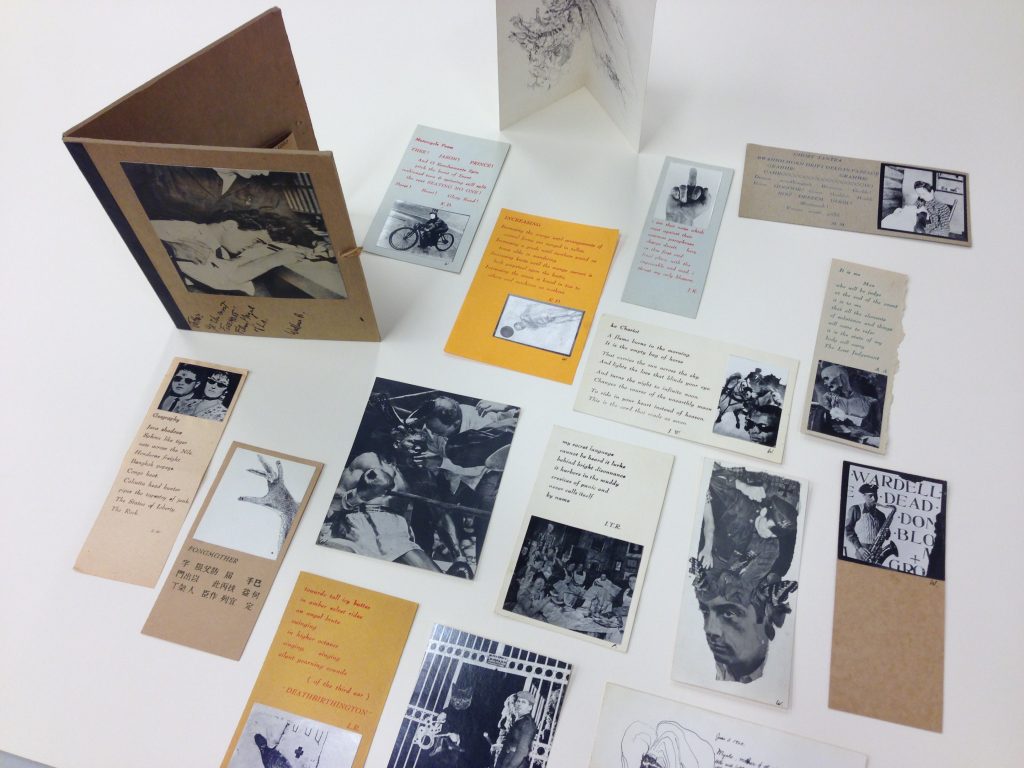

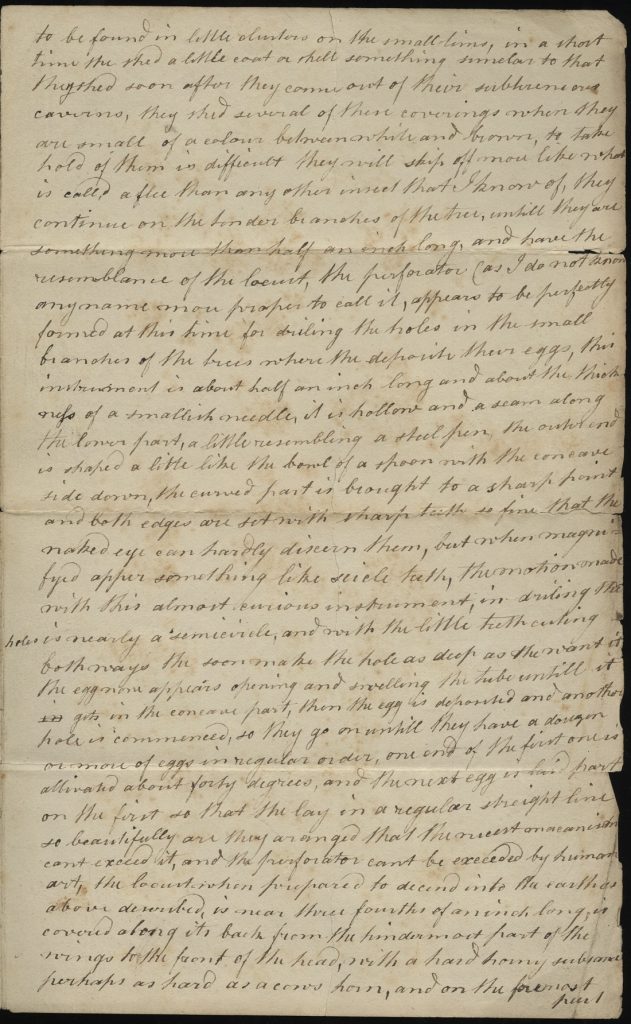

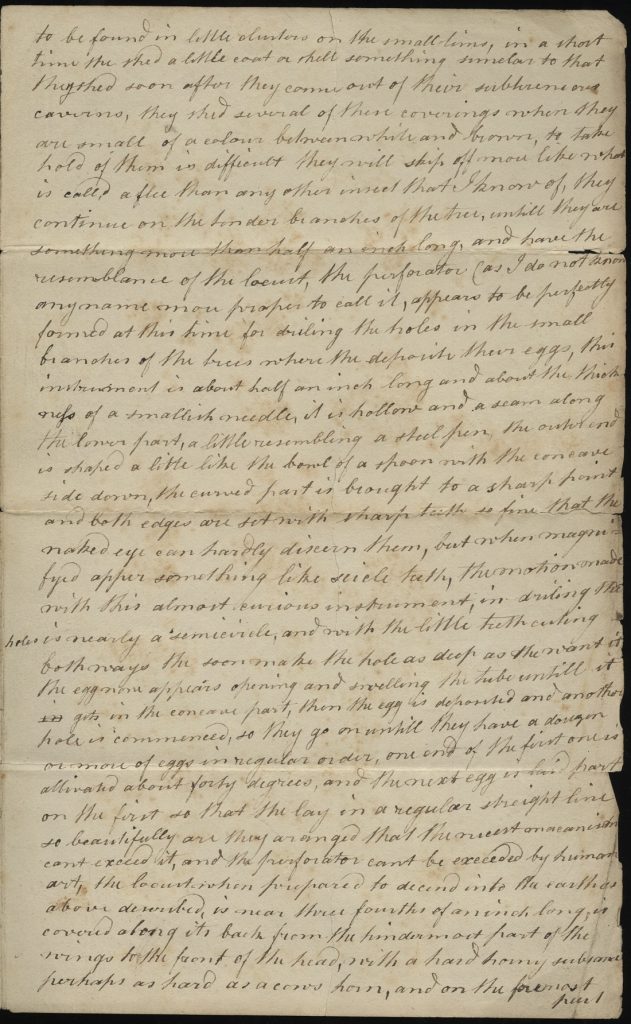

Page two.

to be found in little clusters on the small lims. In a short time they shed a little coat or shell something similar to that they shed soon after they came out of their [subterenious caverns?.] They shed several of these coverings when they are small of a colour between white and brown. To take hold of them is difficult. They will slip off more like what is calld a flee than any other insect that I know of. They continue on the tender branches of the tree, untill they are something more than half an inch long, and have the resemblance of the locust.

The perforator (as I do not know any name more proper to call it) appears to be perfectly formed at this time for driling the holes in the small branches of the trees where She deposits their eggs. This instrument is about half an inch long and about the thickness of a smallish needle. It is hollow and a seam along the lower part, a little resembling a steel pen, the outer end is shaped a little like the bowl of a spoon with the concave side down, the curved part is brought to a sharp point and both edges are set with sharp teeth so fine that the naked eye can hardly discern them, but when magnifyed appear something like [sickle?] teeth. The motion made with this almost curious instrument in driling the holes is nearly a semicircle and with the little teeth cuting both ways they soon make the hole as deep as the want it.

The egg now appears opening and swelling the tube untill it gets in the concave part, then the egg is deposited and another hole is commenced. So they go on untill they have a douzen or more of eggs in regular order. One end of the first one is [elevated?] about forty degrees, and the next egg is laid part on the first so that they lay in a regular streight line. So beautifully are they aranged that the nicest [illegible?] cant exceed it, and the perforator cant be exceeded by human art. The locust when prepared to decend into the earth as above described, is near three fourths of an inch long, is covered along its back from the hindermost part of the wings to the front of the head, with a hard horny substance perhaps as hard as a cows horn,

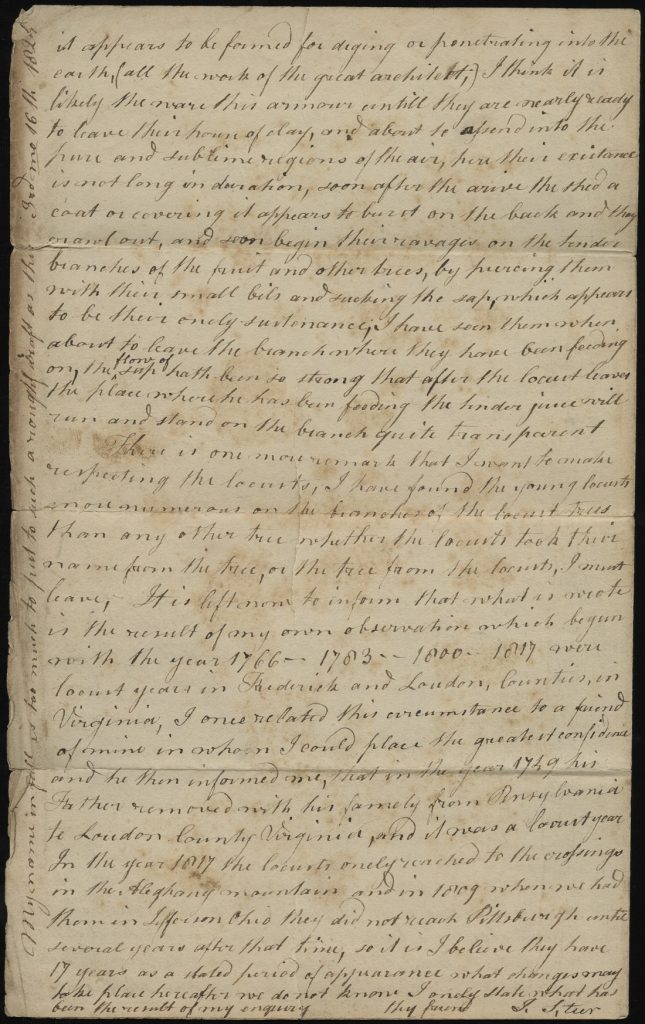

Page 3.

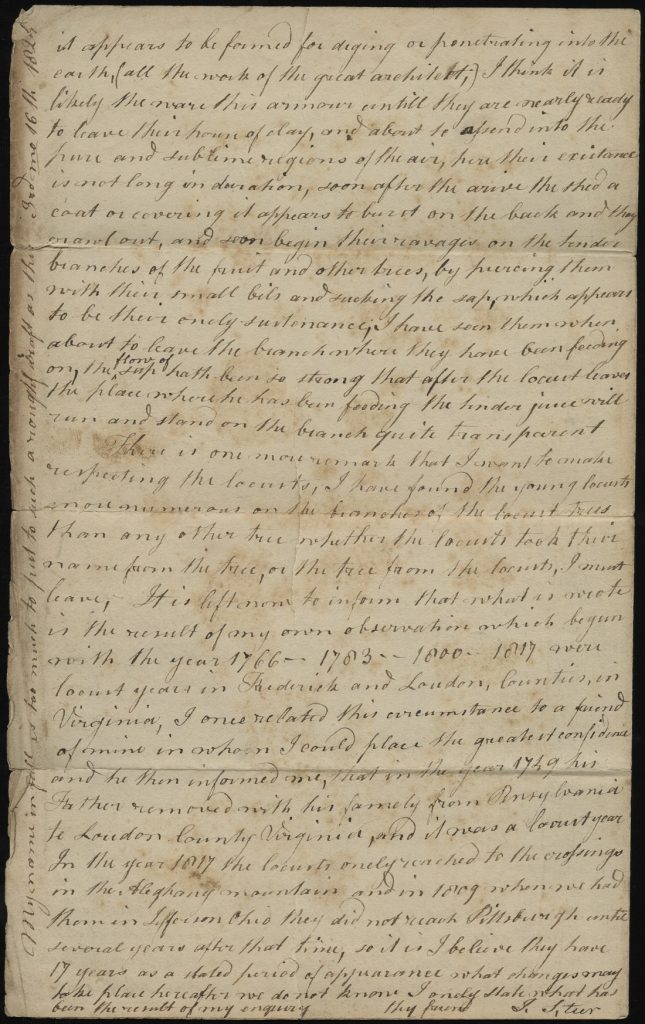

and on the foremost part it appears to be formed for diging or penetrating into the earth, (all the work of the great architect) . I think it is likely they ware this armour untill they are nearly ready to leave their house of clay, and about to ascend into the pure and sublime regions of the air. Here their existence is not long in duration. Soon after they arise they shed a coat or covering. It appears to burst on the back and they crawl out, and soon begin their ravages on the tender branches of the fruit and other trees, by piercing them with their small bits and sucking the sap, which appears to be their onely sustenance. I have seen them when about to leave the branch where they have been feeding on, the flow of sap hath been so strong that after the locust leaves the place where he has been feeding the tender juice will run and stand on the branch quite transparent.

There is one more remark that I want to make respecting the locusts. I have found the young locusts more numerous on the branches of the locust trees than any other tree. Whether the locusts took their name from this tree, or the tree from the locusts, I must leave.

It is left now to inform that what is wrote is the result of my own observation which begun with the year 1766—1783—1800—1817 were locust years in Frederick and Loudon, Counties, in Virginia. I once related this circumstance to a friend of mine in whom I could place the greatest confidence and he then informed me, that in the year 1749 his Father removed with his famely from Pensylvania to Loudon County Virginia, and it was a locust year. In the year 1817 the locusts onely reached to the crossings in the Aleghany mountain and in 1809 when we had them in Jefferson Ohio they did not reach Pittsburgh until several years after that time, so it is I believe they have 17 years as a stated period of appearance. What changes may take place hereafter we do not know. I onely state what has been the result of my my enquiry

Thy friend

J. S

My name in full is too much to put to such a rough draft as this 3rd mo 16th 1824

Page 4.

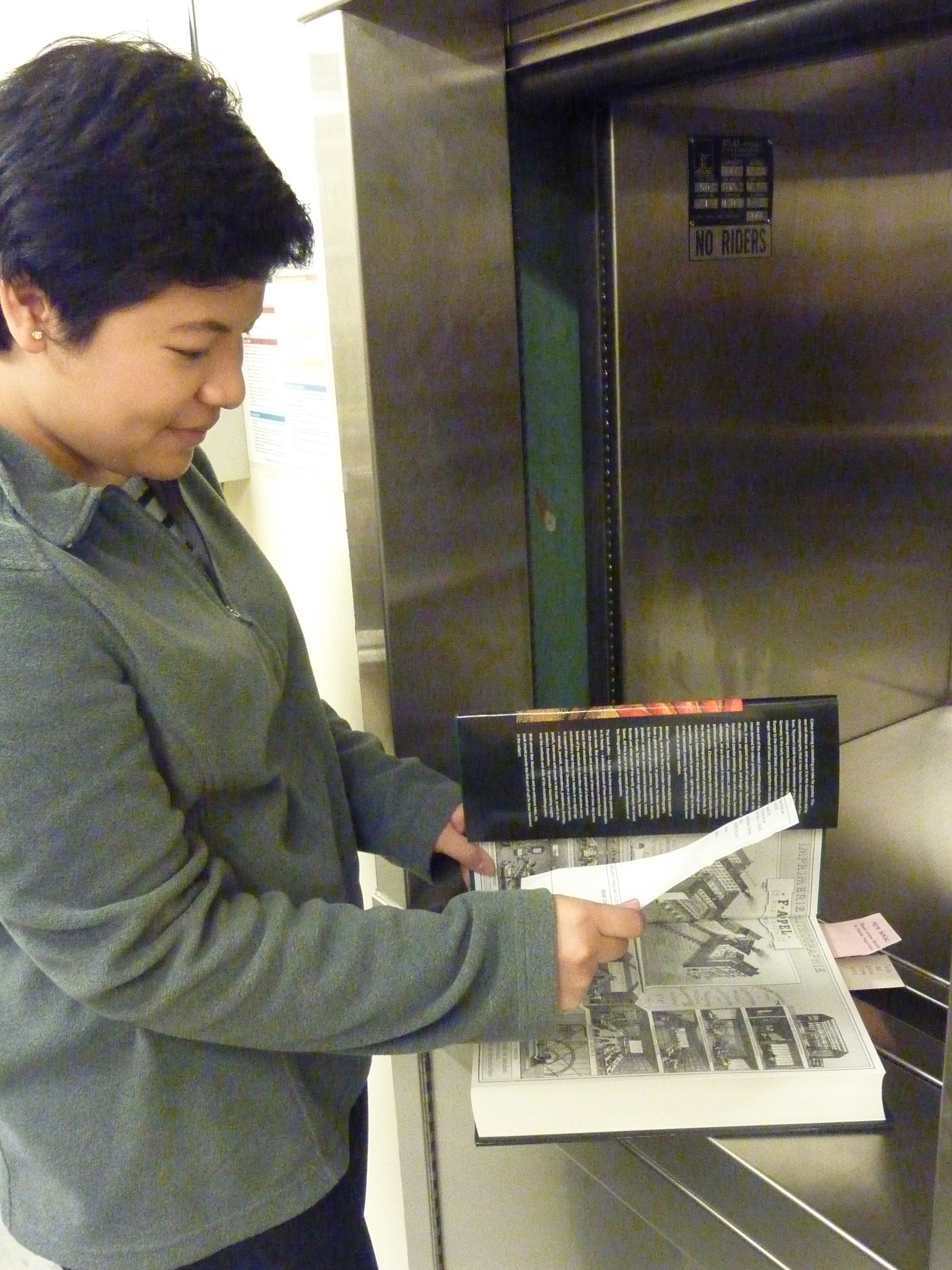

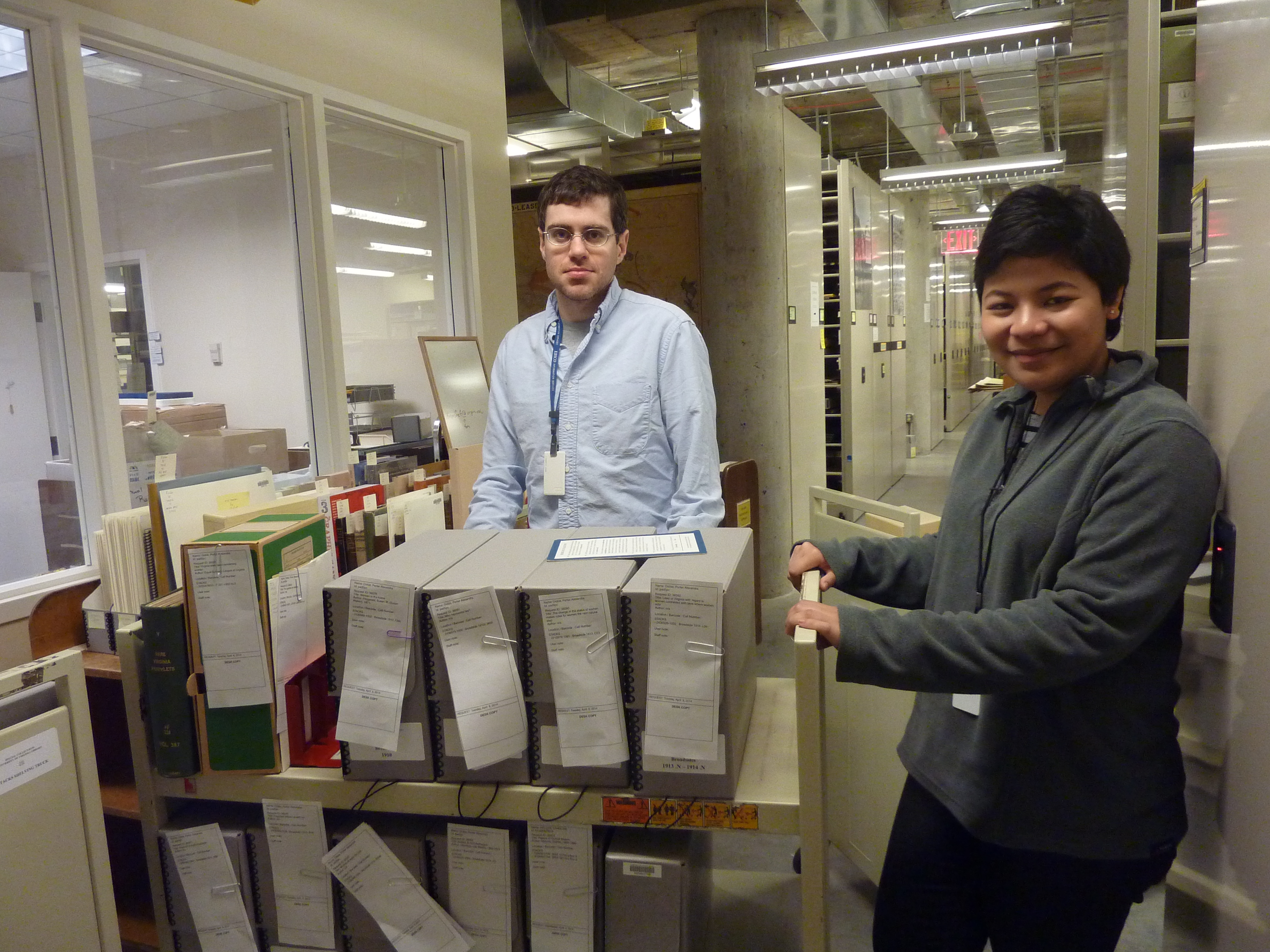

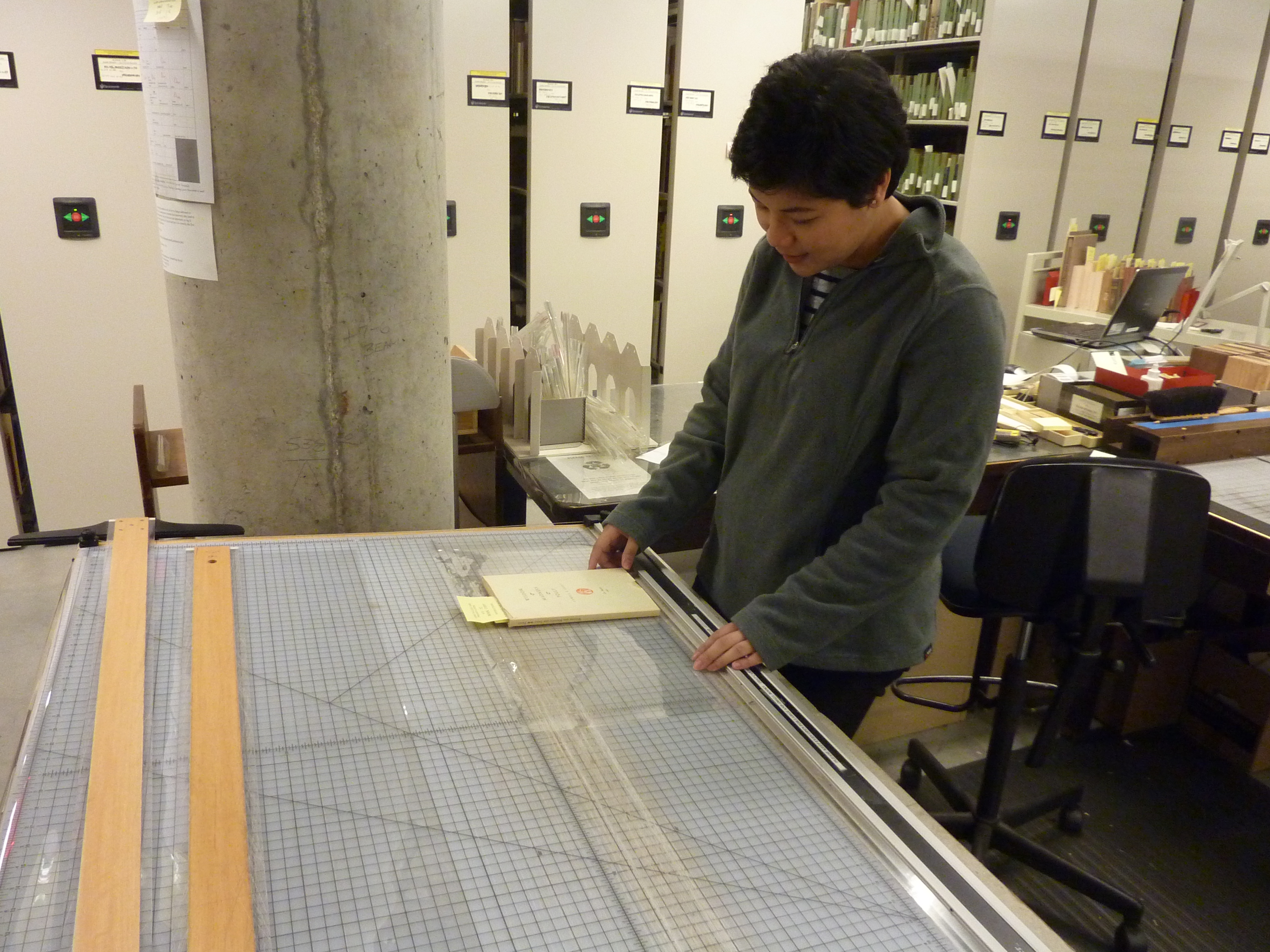

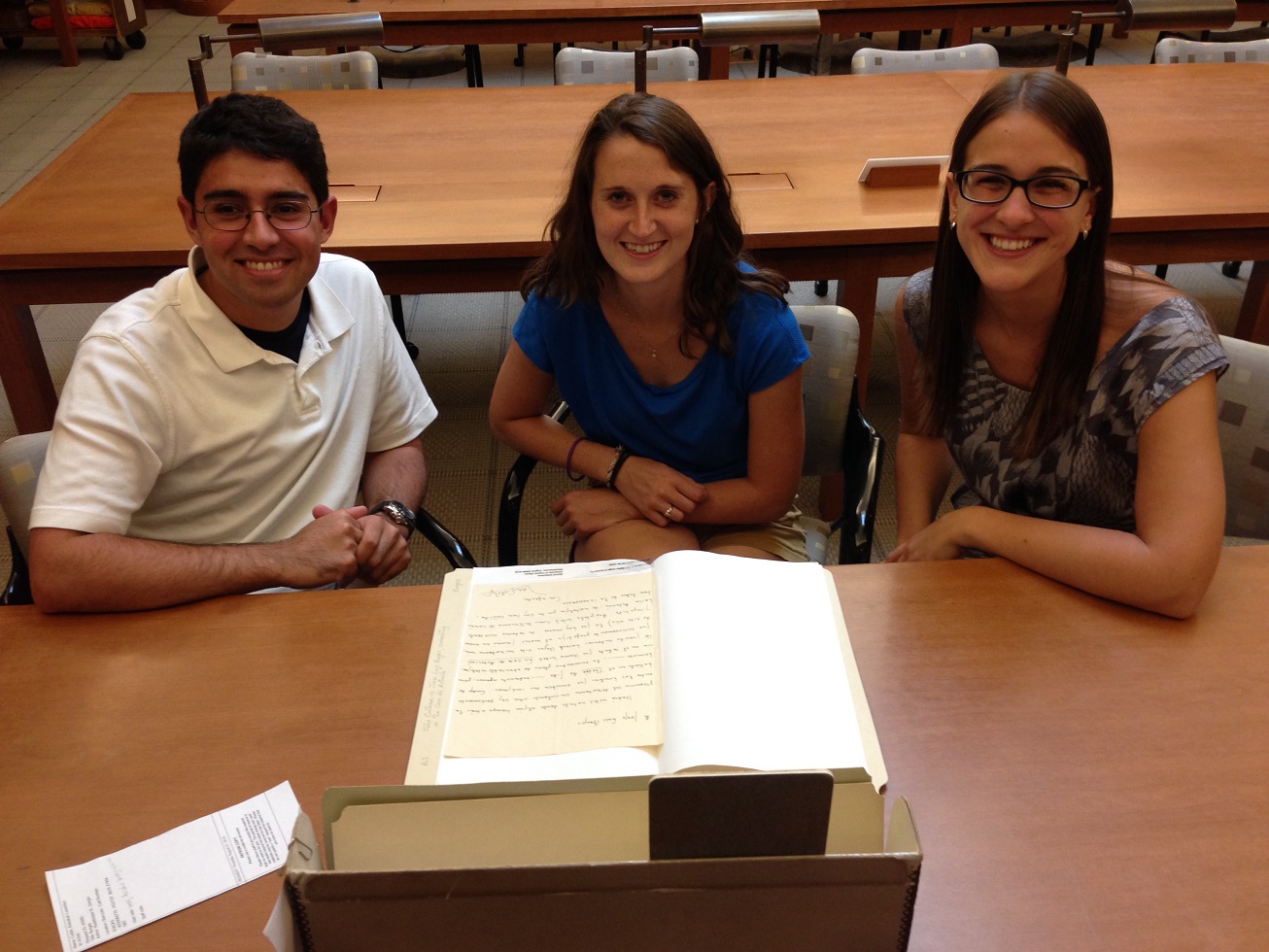

A few days before the semester begins, our reading room generally gets pretty quiet, since summer visitors have headed home and our own faculty are busily preparing for the semester. So I was delighted to find this trio poring over materials together at the front table this afternoon, looking extremely excited and even a bit giddy. Some quick investigating revealed that they are (left to right) Tommy Antorino, Rebekah Coble, and Maggie Czerwien. They are brand new Ph.D. students in the Spanish Department. They met at their department orientation on Monday and learned about Special Collections at a Graduate Student Resources panel yesterday. Finding themselves with a bit of free time on their hands this afternoon, they headed down Under Grounds, and after learning the ropes from our reading room staff, found themselves in front of a Jorge Luis Borges manuscript. Hence, the giddiness.

A few days before the semester begins, our reading room generally gets pretty quiet, since summer visitors have headed home and our own faculty are busily preparing for the semester. So I was delighted to find this trio poring over materials together at the front table this afternoon, looking extremely excited and even a bit giddy. Some quick investigating revealed that they are (left to right) Tommy Antorino, Rebekah Coble, and Maggie Czerwien. They are brand new Ph.D. students in the Spanish Department. They met at their department orientation on Monday and learned about Special Collections at a Graduate Student Resources panel yesterday. Finding themselves with a bit of free time on their hands this afternoon, they headed down Under Grounds, and after learning the ropes from our reading room staff, found themselves in front of a Jorge Luis Borges manuscript. Hence, the giddiness.