This week we are pleased to share a guest post from Nichole LeFebvre. Nichole is a Poe/Faulkner Fellow at the University of Virginia, where she teaches creative writing. Her poems can be found in Prairie Schooner and Barrelhouse and recent prose in Lit Hub, Paper Darts, and Vol. 1 Brooklyn. She is the Nonfiction Editor of Meridian: A Semi-Annual and is at work on a memoir.

Researchers may have met Nichole at Special Collections, where she used to work as a graduate student assistant in the Reference department. Now, she’s using that experience to incorporate original materials into her creative writing instruction.

Working at Special Collections, I’d often find myself in awe. Researchers would carry diaries and ledgers to the reference desk, pointing out their surprising finds. Reading Faulkner’s grocery list, I’d wonder about his carbo-loading: “breadsticks, bread, breakfast bread.” I’d show students how to aim a black light at a seemingly blank book. One afternoon, a librarian grinned and said, “Have you seen the bone fragment from the Revolutionary War?”

When I had the chance to design a themed writing workshop, I knew exactly where to go: down the spiral staircase, under the skylights. How many stories hid, waiting latent, below our feet?

Fourth-year Halley Townsend recalls the first time she held an artifact: “There’s something immutable in the feeling of touching history that can be gleaned nowhere else.” And that’s exactly right: in fiction, we focus on creating sensory-rich scenes for the reader. Students in my class, “Unearthing Fiction,” were able to feel that texture first-hand, noticing minor details otherwise forgotten with time.

“Being an engineer, I preferred to look at objects that were manmade and complex,” says Daryn Govender, hailing all the way from New Zealand. For his stories, he studied a field compass from World War II as well as a New Tyme Edison light bulb, patented in 1881. Because these objects are catalogued without specific historical context—letters or diary entries from their owners—Govender felt “allowed to write more freely, unconstrained by a pre-existent scenario or background story.”

Of our first visit to Special Collections, second-year Caroline Bohra writes, “My mind started to race thinking of all the people who could have come in contact with these objects. I could not help but wonder what made these specific objects so special that they had been chosen to be saved and preserved? And what modern artifacts would be deemed important enough to be studied years from now?”

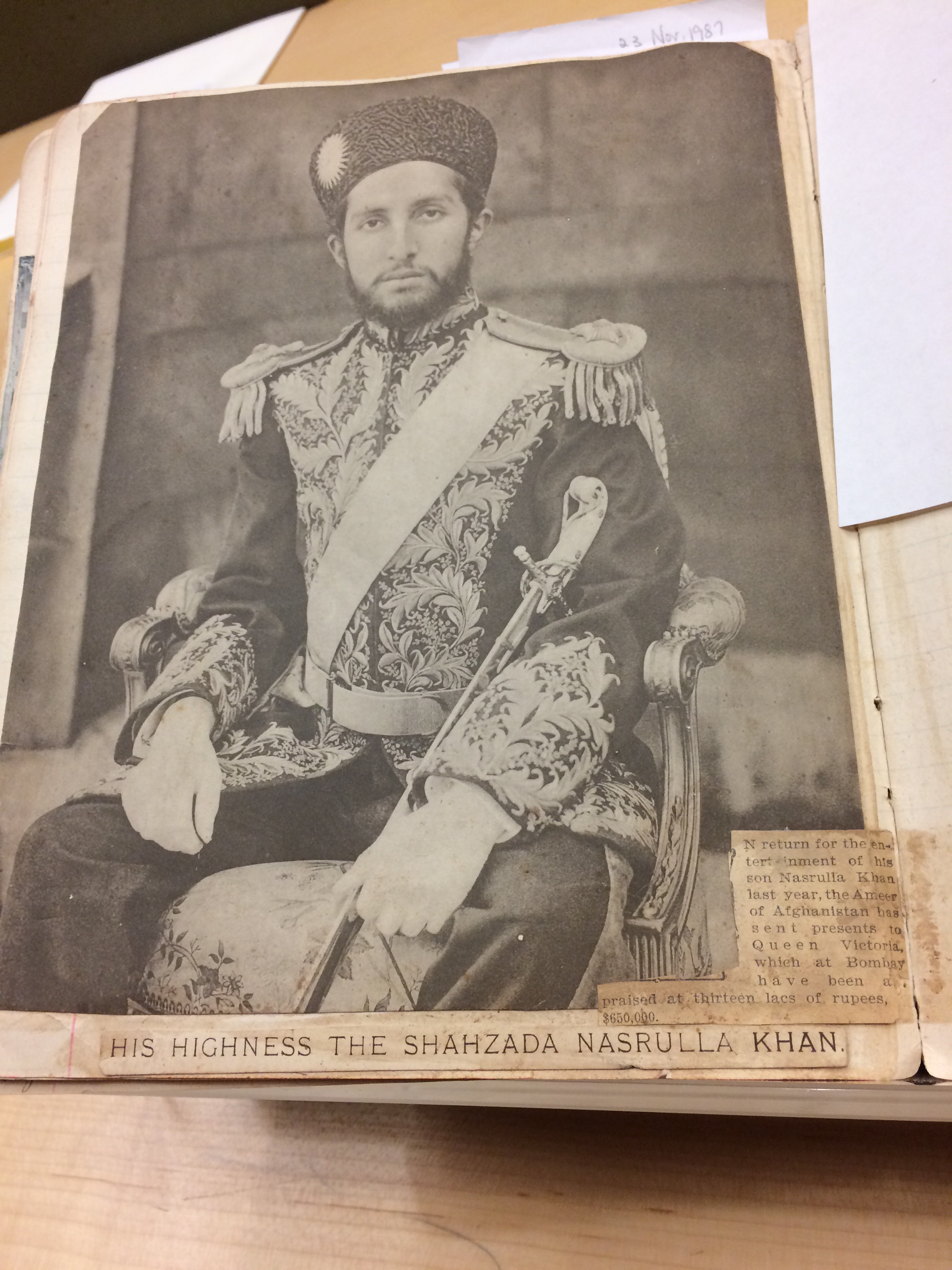

The travel scrapbook of Nina Withers Halsey, 1895, inspired Alexander O’Connor to write about a self-taught American teenager who meets and impresses the Shahzada Nasrulla Khan with her knowledge of tenuous British-Afghan relations (MSS 10719-b). Photograph by Alexander O’Connor.

How archives shape history was on our mind, all semester. Fiction is likewise political: whose stories are told, and therefore remembered? Third-year Hunter Wilson wondered how to write “historical women, on the one hand acknowledging that women often lacked basic rights, while on the other, respecting the character.” She decided to set her first story in 17th Century Scotland, inspired by the ballad of the Outlandish Knight. The twist? It’s the princess who uncovers the dreamy knight’s murder plot. “I wanted Isabel to act accurately in her historical context, but also give voice to the likely frustrations that came with her place in history.”

Fourth-year Matin Sharifzadeh enjoyed the depth of creative control he had over his work. “When we would go down into the library, the artifacts weren’t there for us to write about. They were there for us to create a world.” And like history itself, those worlds weren’t always pretty: the rope used in the hanging of a Charlottesville mayor inspired Sharifzadeh to write “a psychological thriller involving a mentally ill serial killer in the late 19th Century.”

Students faced, first-hand, the challenges of writing historical fiction. First-year Julia Medina found an embroidered handkerchief “depicting a group of children and a school teacher from the early 20th century.” This morphed into her story of an exploitative school for gifted children. But she couldn’t have her characters talking in today’s slang. To research the nuances of 1940s speech, Medina found “a collection of letters than an ordinary military man wrote to his wife.” These “seemingly mundane letters” allowed her to imagine “what he felt, how he talked, and where he’d been.”

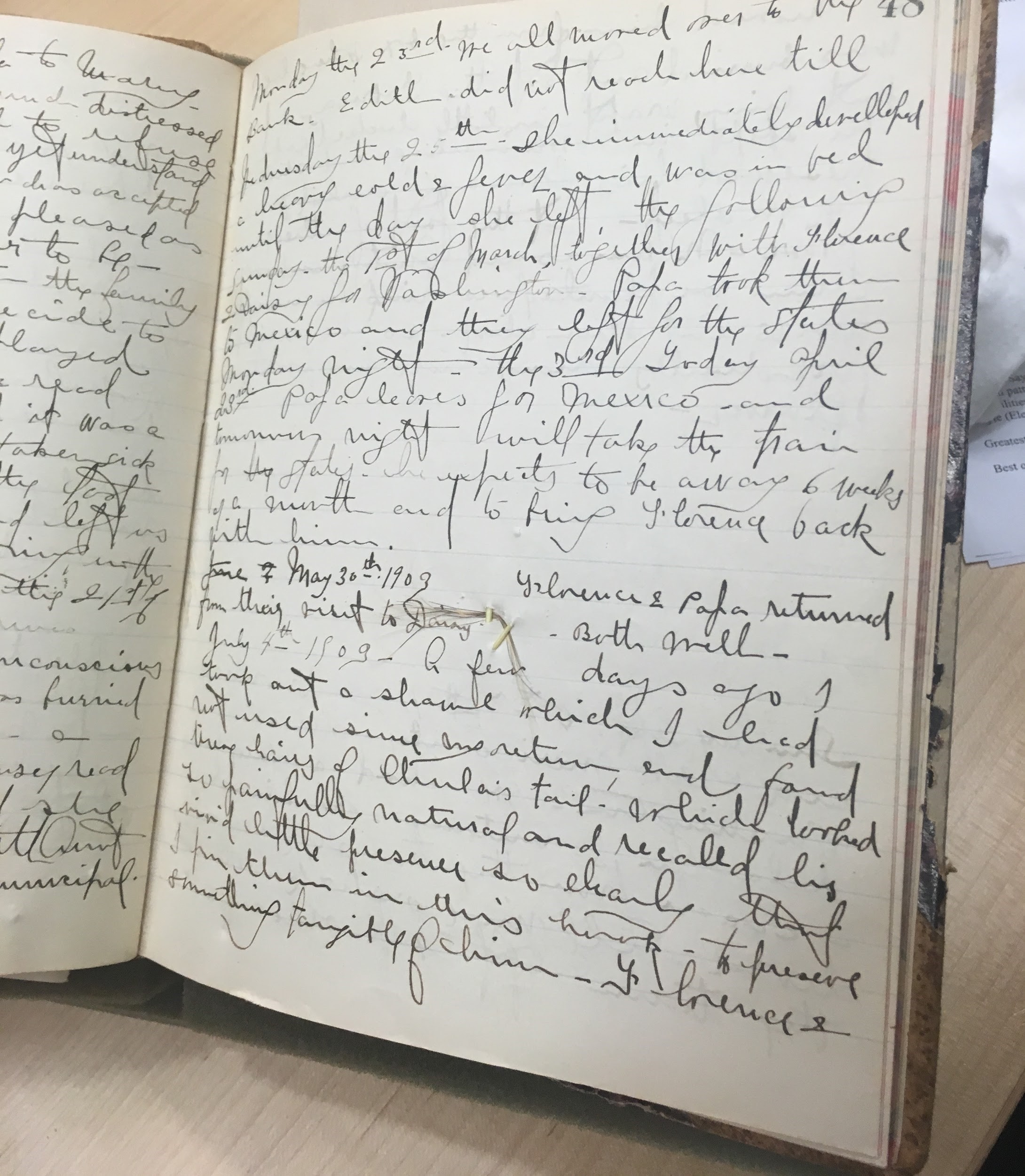

Some details will remain buried with time, unless you, dear reader, can read this handwriting. Elizabeth Oakes-Smith’s diary, 1861 (MSS 38-707-a). Photograph by Veronica Sirotic.

The question of historical accuracy recurred throughout the semester. How do we earn a reader’s trust when we aren’t historians, we’re writers?

The answer? More reading, more research, and a deep personal connection to the material. Second-year Veronica Sirotic pored over radical feminist and music magazines from the 60s, 70s, and 80s, inspired by not only the articles, but the advertisements, as well. A few students returned to the feminist periodical The Monthly Extract including first-year Megan Lee, who tried to get into the mindset of both a feminist and her “tolerant husband,” digging up manuscript boxes of period photographs to build images of these characters, in her head.

Students realized when they were most curious, most personally engaged, their own fiction was at its strongest. Caroline Bohra found a children’s book from 1927 and was “struck by a sort of nostalgic happiness,” changing her initial character’s personality as she researched real-life author Christopher Morley, who “believed in the magic of childhood and instilled that in his children, specifically Louise Morley Cochrane, who went on to produce a children’s television series, following in her father’s footsteps, as well as work directly for Eleanor Roosevelt.”

Finding patterns across time was another an important way in. First-year Alexander O’Connor was struck by former Secretary of State John Hay’s life story. “Two out of the three Presidents he worked for, Abraham Lincoln and William McKinley, were assassinated while he worked for them, and the third, Theodore Roosevelt, experienced an assassination attempt but lived. Coincidence? I think not!”

The class also sought guidance from UVa’s own Jane Alison, Professor and Director of Creative Writing. Students read Alison’s Ovid translations and a section of her novel The Love-Artist, curious how she was able to write from the point of view of the ancient poet. Alison explained her range of primary and secondary sources, as well as her trip to Rome, to see and imagine how the ruins once looked. She placed herself inside the poet’s shoes, inside his head, tried to imagine how he saw and described the world around him.

Alison urged the students to recognize the overlap between historical fiction and memoir, a comment that struck Veronica Sirotic as especially true: “We have the power to shape history to our liking.” Alexander O’Connor, agreed, noting that even “memoir is a retelling of history through the author’s lens.”

“‘Unearthing’ means to dig up, to discover, to recover in an active sense,” writes Halley Townsend. “Throughout the semester, that definition has aligned more and more with my creative writing; I feel like I’m discovering or rediscovering something that was already there in my mind.”

All semester long these students uncovered and re-imagined artifacts into fiction, resulting in eighteen riveting short stories. Whether setting their work in the distant past, or today’s world, they used history to deepen the story’s emotional content and lasting impact—looking forward, while looking back.

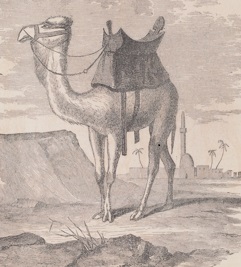

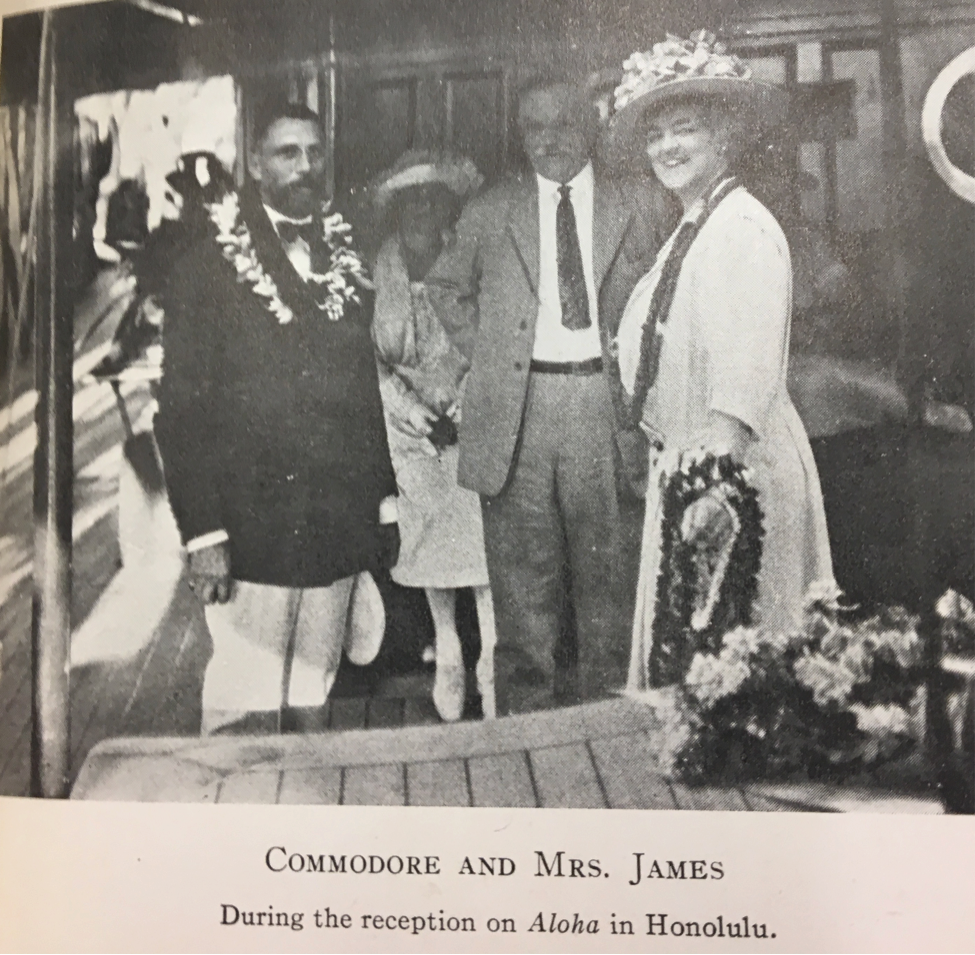

“I took this image from a couple’s autobiography about their circumnavigation in the early 1920s,” writes student Halley Townsend. “Based on this picture, I wanted to imagine their relationship. What kind of relationship survives on a small boat during stressful circumstances?”

(G440 .V8 1923).

Thank you, Nichole, for sharing your students’

marvelous insights with us.