This is the third in a series of four posts, spotlighting the mini-exhibitions of students from USEM 1570: Researching History. This is the abridged version of the students’ projects, featured at their outreach program, Tales from Under Grounds.

“Save the Date,” Fall 2014. (Photograph by Caroline Newcomb)

***

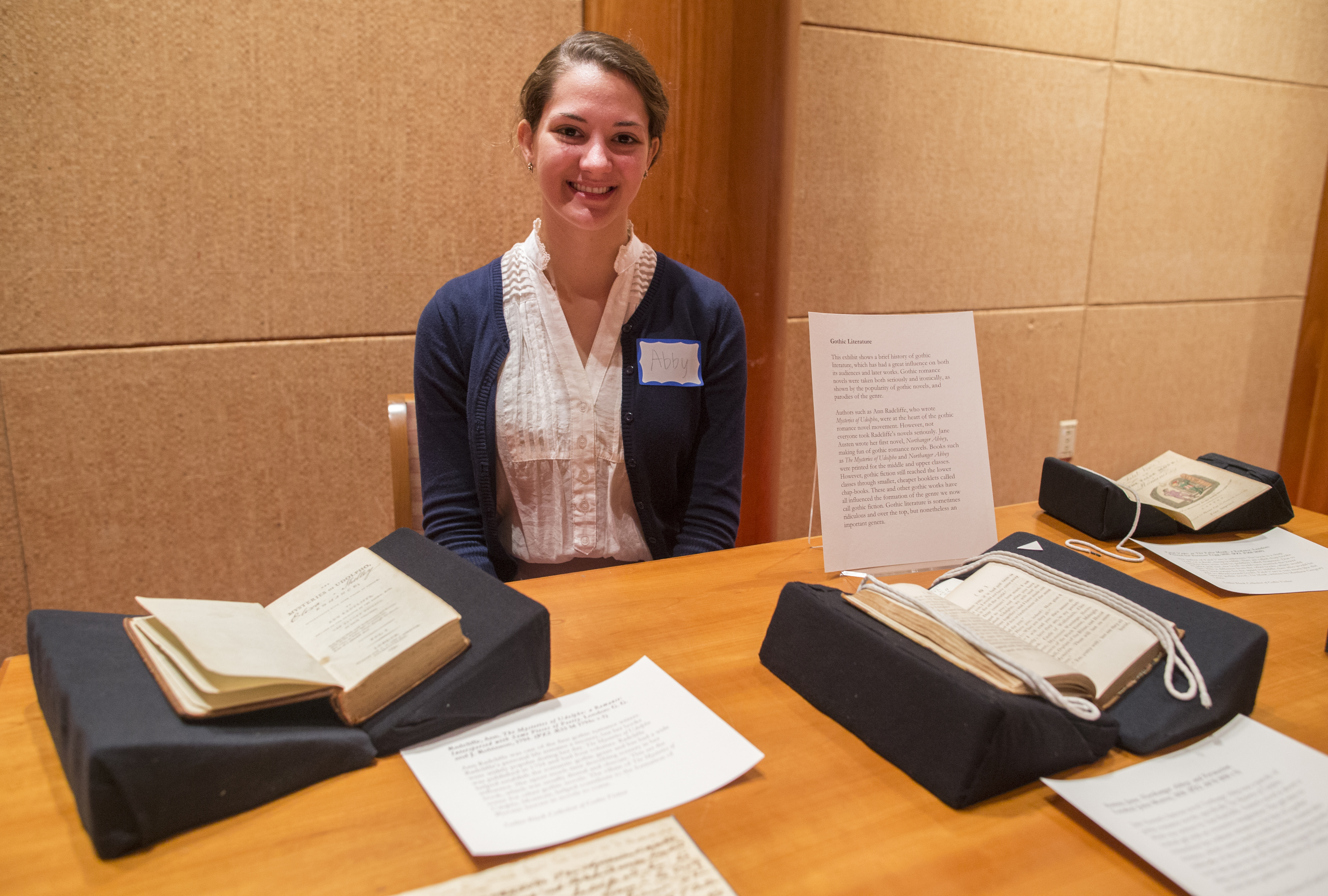

Abby Ceriani, First-Year Student

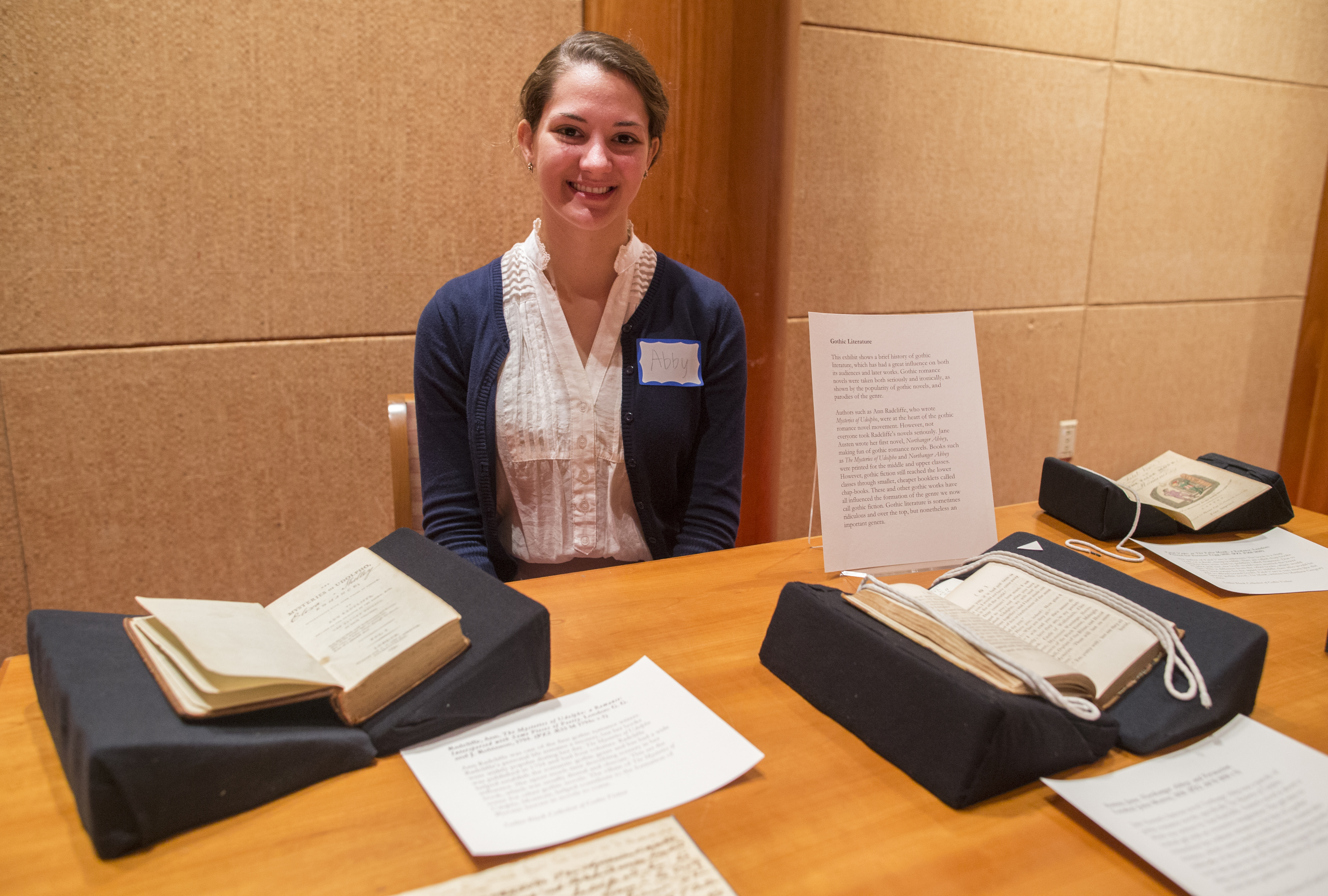

Photograph of Abby Ceriani by Sanjay Suchak, November 19, 2013.

Gothic Literature

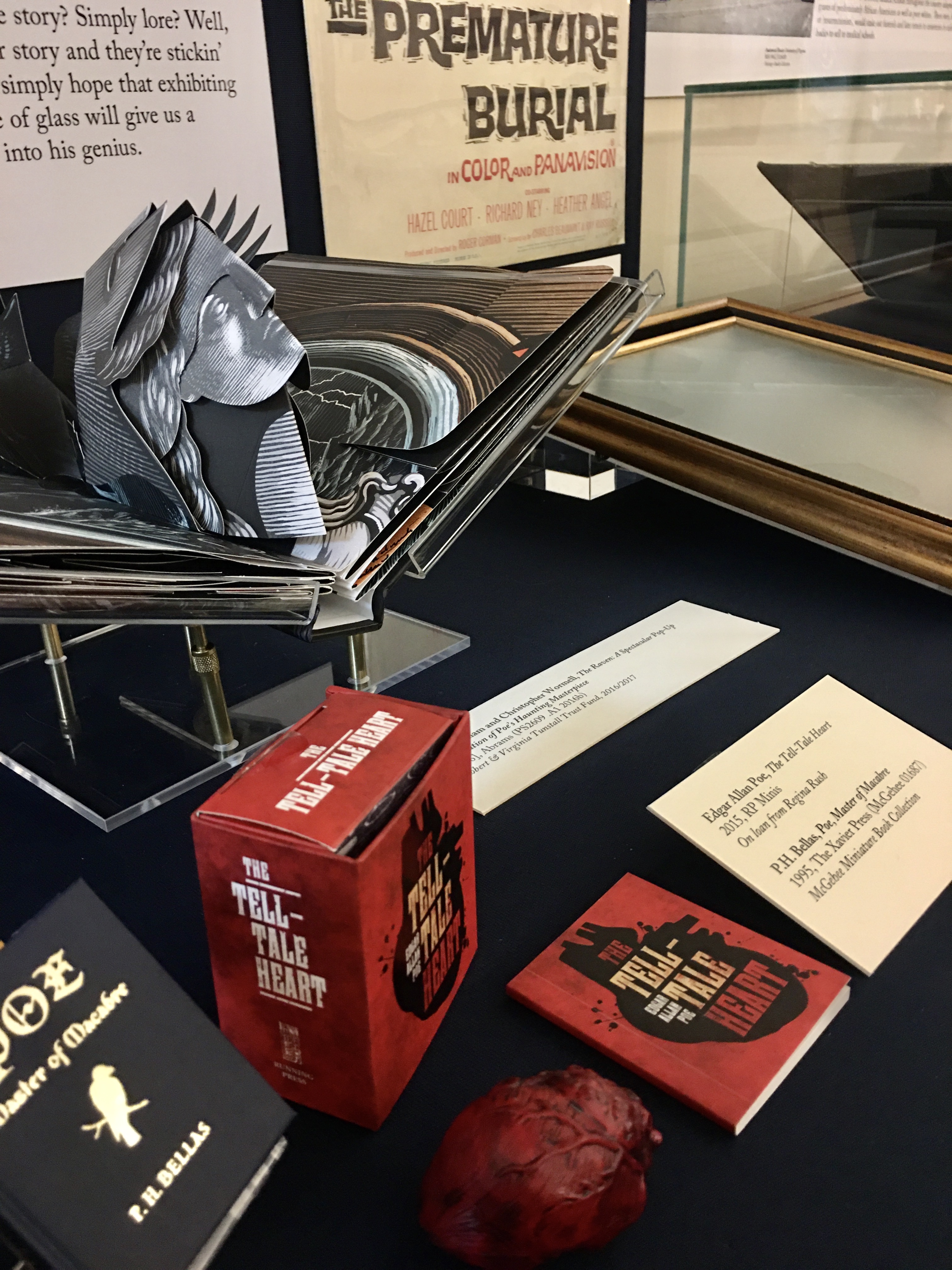

This exhibit shows a brief history of Gothic literature, which has had a great influence on both its readership and later literary works. Gothic novels were taken both seriously and ironically as shown by the popularity of the genre and its parodies.

Authors, such as Ann Radcliffe who wrote The Mysteries of Udolpho, were at the heart of the Gothic novel movement. However, not everyone took Radcliffe’s novels seriously. Jane Austen wrote Northanger Abbey, making fun of Gothic romance novels.

To appeal to a broad audience, Gothic fiction was produced in multiple volumes as well as in smaller, cheaper booklets called chap-books. These books, with their elements of romanticism, horror, and mystery have thrilled and entertained audiences over the centuries.

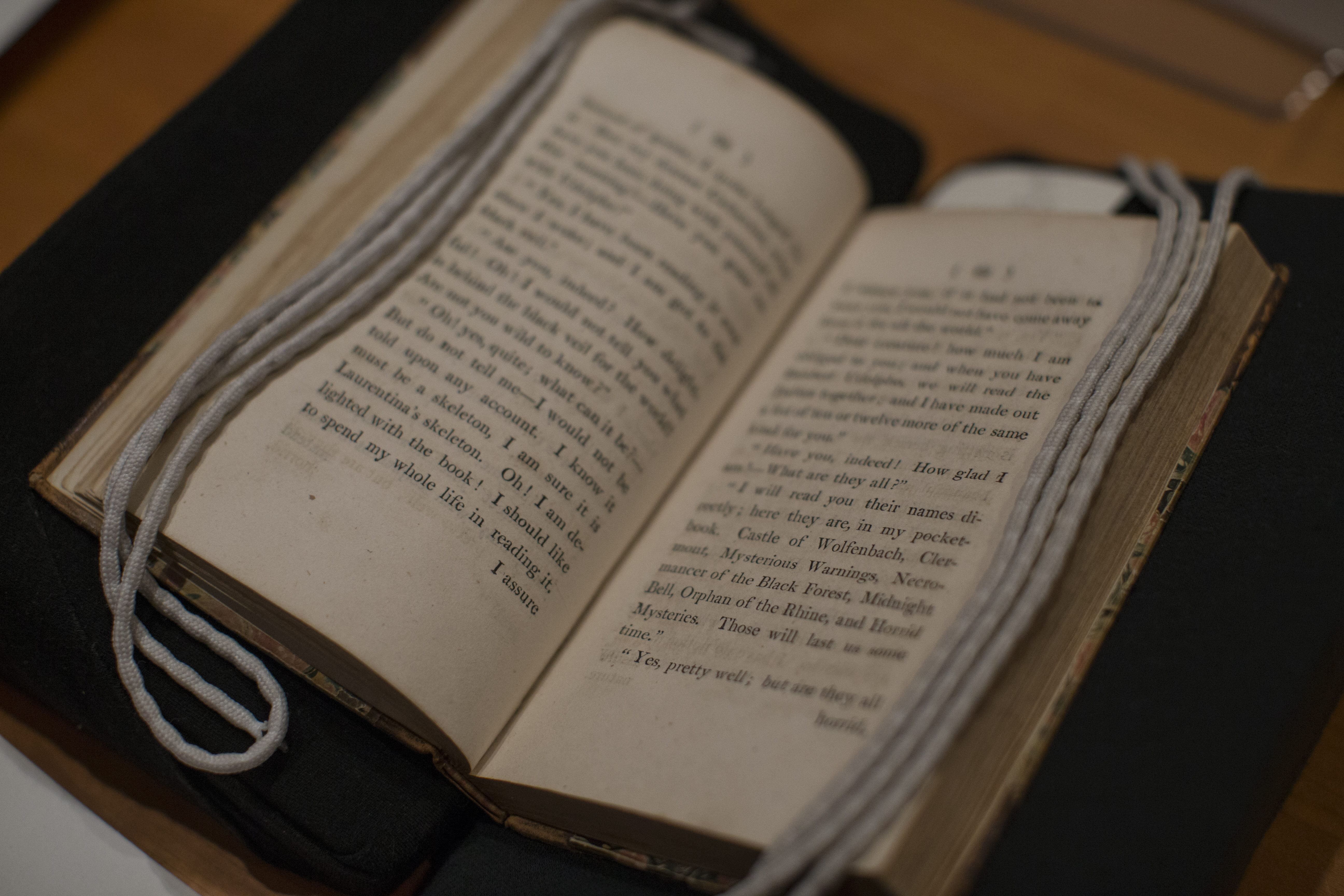

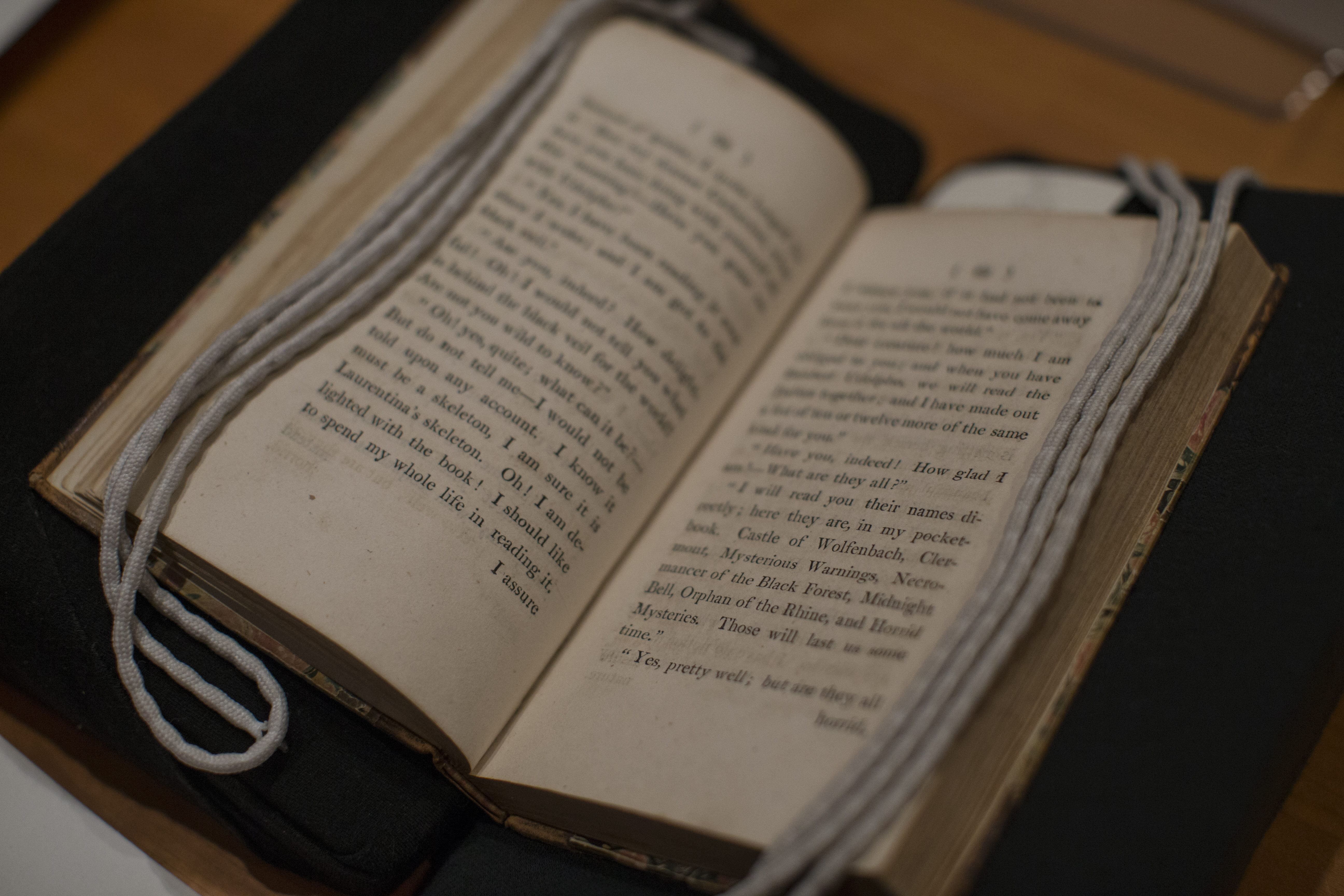

Austen, Jane. Northanger Abbey: and Persuasion. London: John Murray, 1818. Jane Austen’s famous novel Northanger Abbey was a parody of Gothic romance novels, specifically, Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho. Austen’s novel is about a girl with an overactive imagination. She tries to imagine her ordinary situation as that of a Gothic romance, which causes her much trouble. Austen also makes use of the iconic Gothic scenery by having much of the book take place in an old Abbey. On page 69 of Northanger Abbey, Austen refers to The Mysteries of Udolpho and lists several other Gothic novels. (PZ2 .A8 N 1818 v.1. Sadlier-Black Collection of Gothic Fiction. Photograph by Sanjay Suchak)

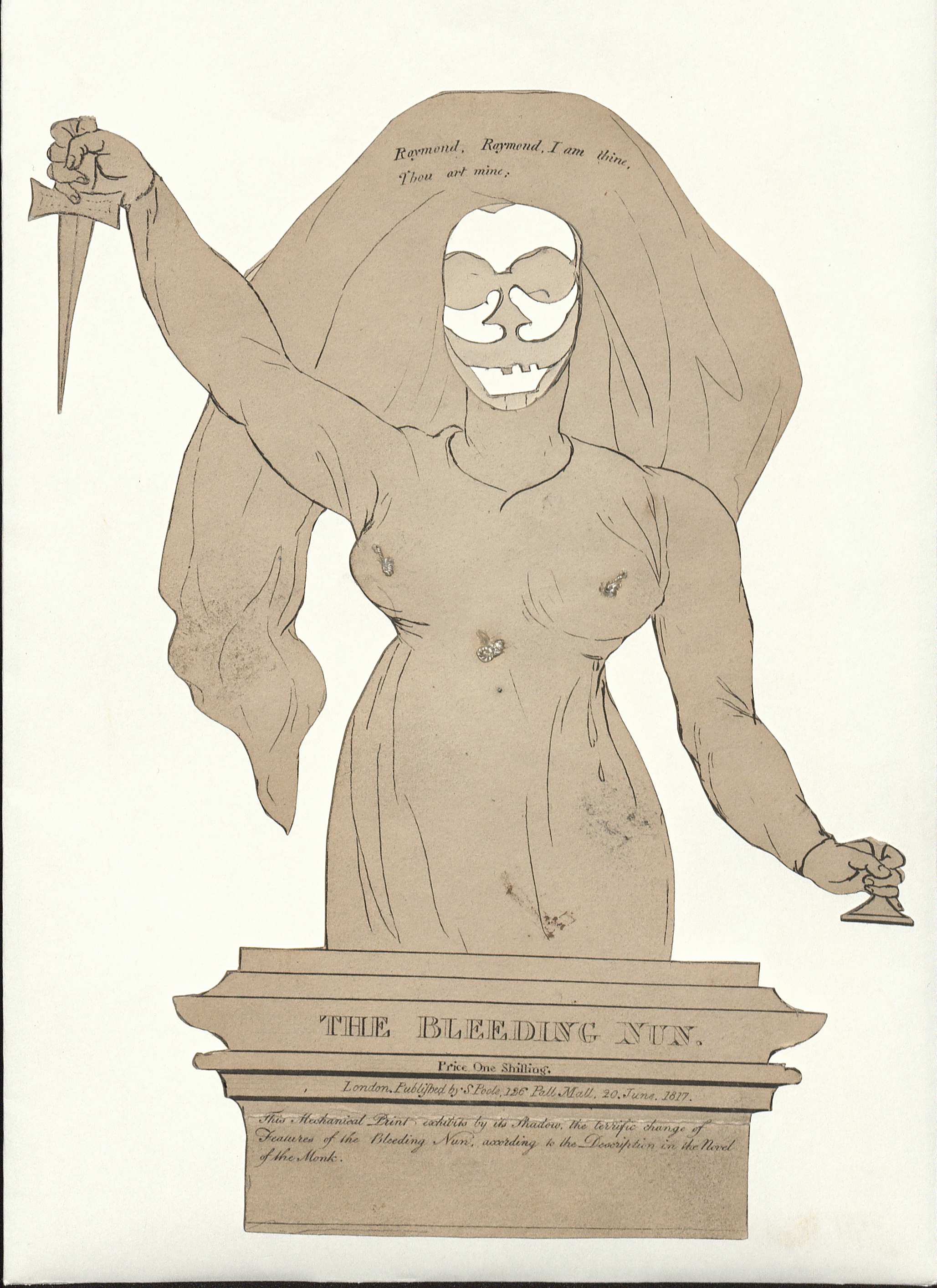

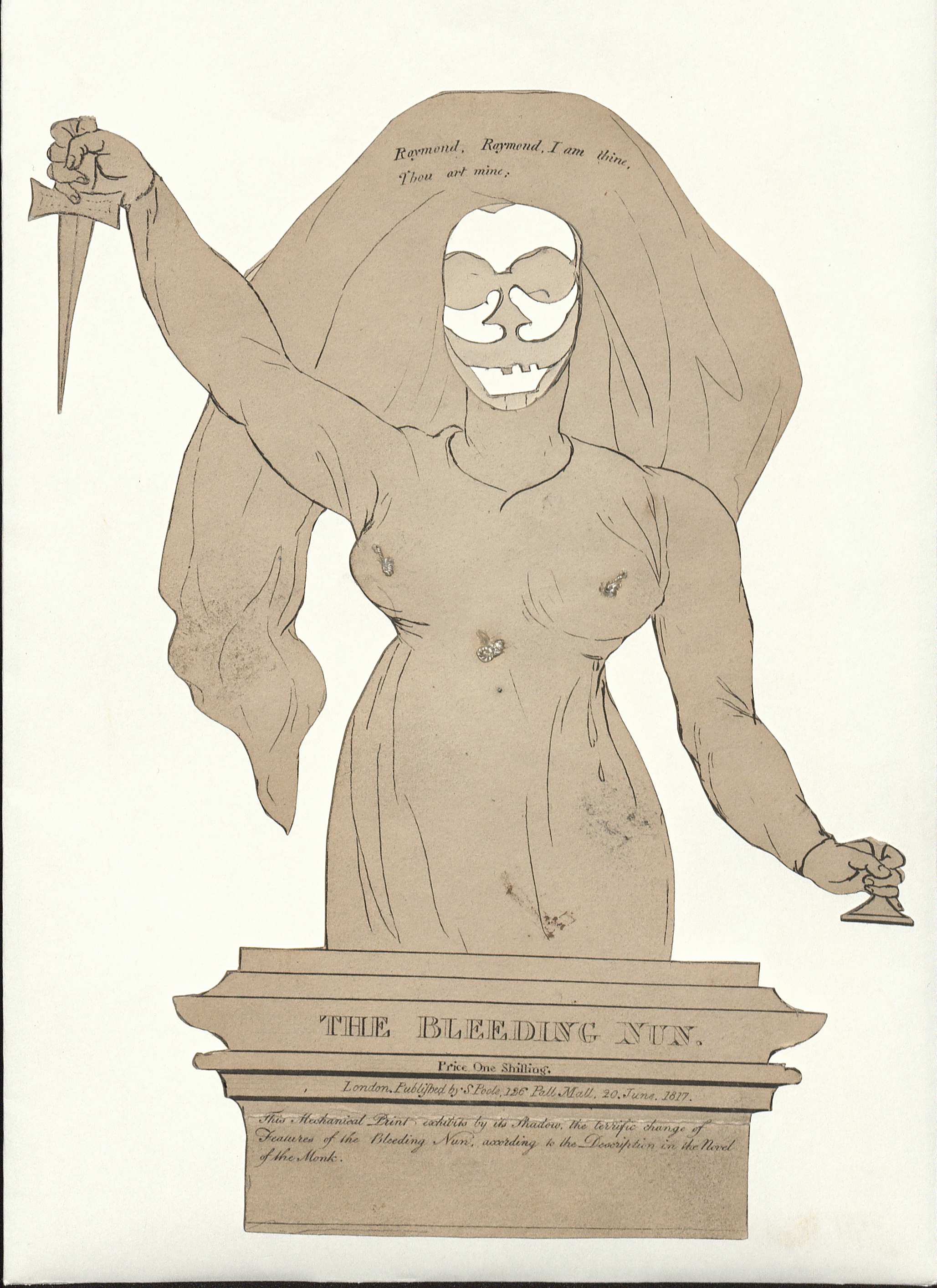

The Bleeding Nun, a Mechanical Print from The Monk. London: S. Poole, 1817. The writing on the bottom of “The Bleeding Nun” says “This mechanical print exhibits by its shadow, the terrific change of features of the bleeding nun, according to the description in the novel of The Monk.” The Monk, written by Matthew Gregory Lewis, is an iconic Gothic novel. The mechanical print shows the nun with normal features and can be changed to show the nun with a skull’s face. (Broadside 1817 .B54. Sadlier-Black Collection of Gothic Fiction. Image by Petrina Jackson)

***

Becca Pryor, First-Year Student

Becca Pryor talks to a guest about her exhibition, November 19, 2013. (Photograph by Sanjay Suchak.)

Meeting Marjorie

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings was born on August 8, 1896 in Washington DC. At 14, Rawlings’ short stories were published in the Washington Post. During her studies at the University of Wisconsin, she wrote for the Wisconsin Literary Magazine. While living in Louisville, KY and Rochester, NY, Rawlings wrote for local journals as well. After feeling restless living in cities, Rawlings and her husband moved to the rural coast of Florida. It was here where Rawlings’ writing career really took off. She drew inspiration from the people, nature, and interactions between the two to shape her novels, such as The Yearling, and short stories.

Rawlings exposed a side of American culture that had not been shared. She lived in the scrub with a family in order to experience their lifestyle and learn how to appreciate their high spirits amidst low circumstances. By fully immersing herself in the culture of Florida, she was able to write from a genuine and sincere perspective.

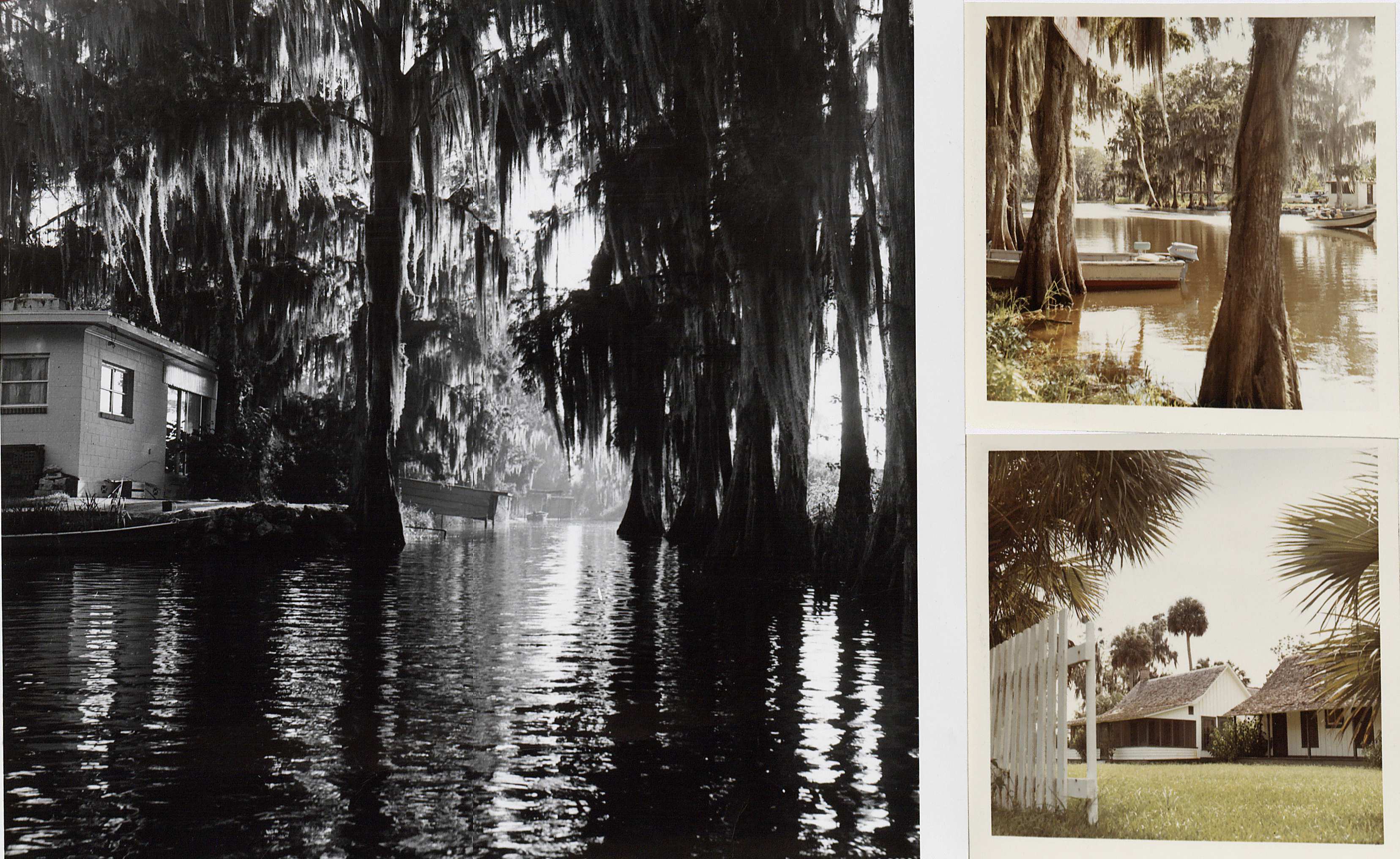

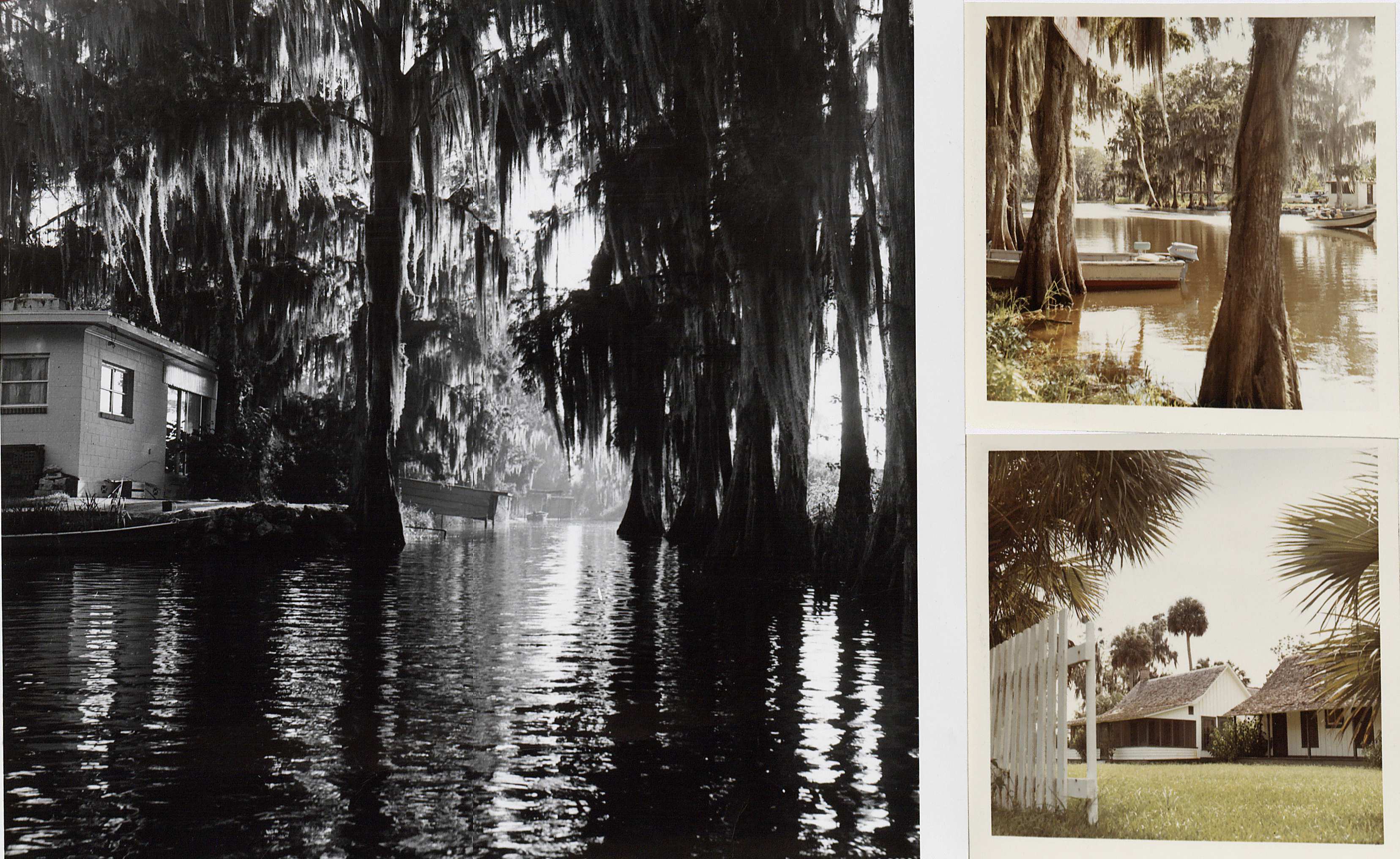

Photographs of Rawlings’ Cross Creek, Florida Home. These photos were developed on October 23, 1968, which is 15 years after Rawling’s death. Rawlings and her husband bought a seventy-two-acre farm in Cross Creek because of the great beauty she associated with the area. Cross Creek inspired Rawlings to write many short stories, which were published in Scribner’s Magazine. After some time at Cross Creek, Rawlings moved in with a family who resided in the scrubs of the inland of Florida, so that she could experience firsthand life in rural Florida. Here, the honesty of the people in the scrub amidst their challenging circumstances impressed Rawlings. (MSS 6785-d. Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature. Image by Petrina Jackson)

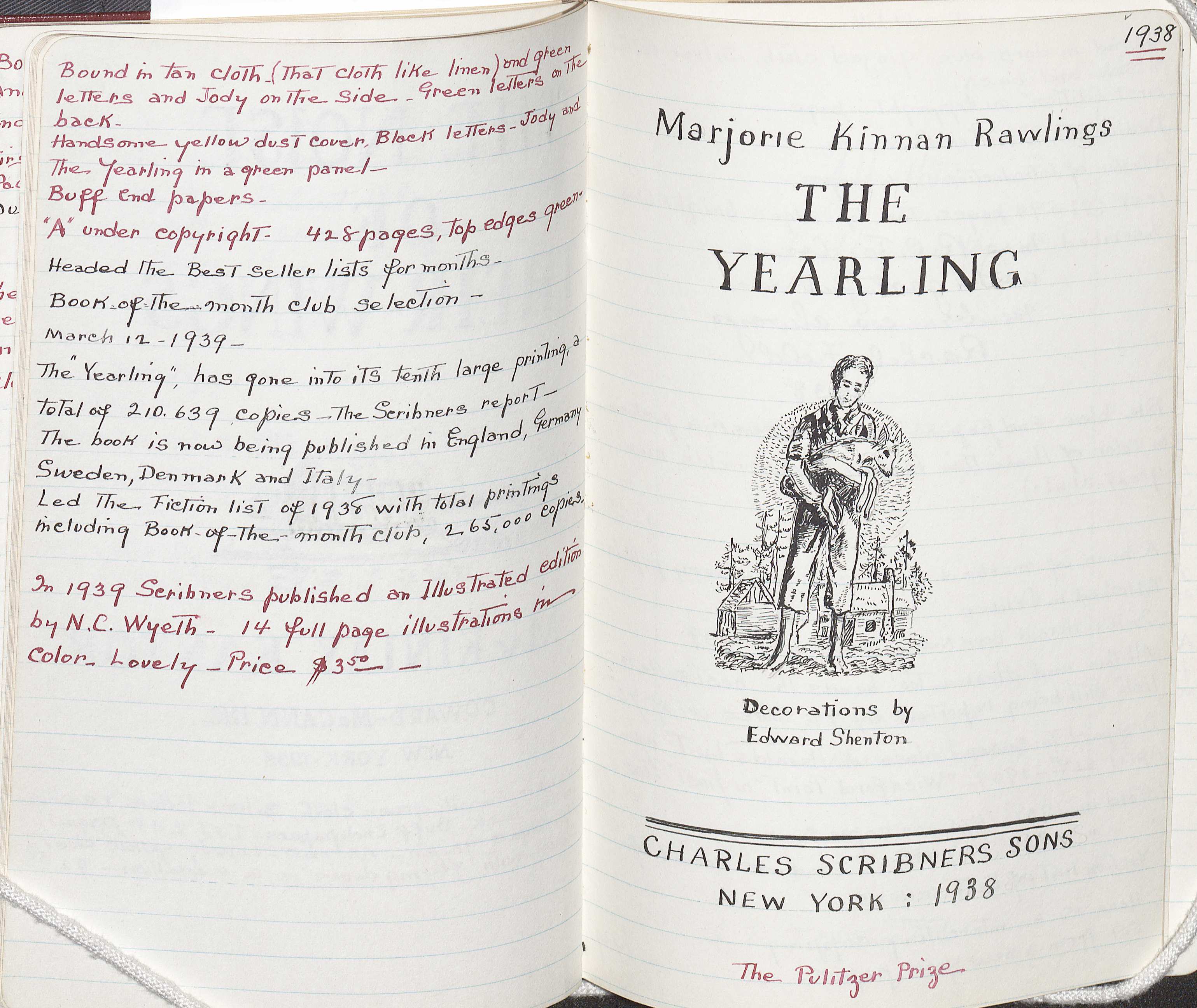

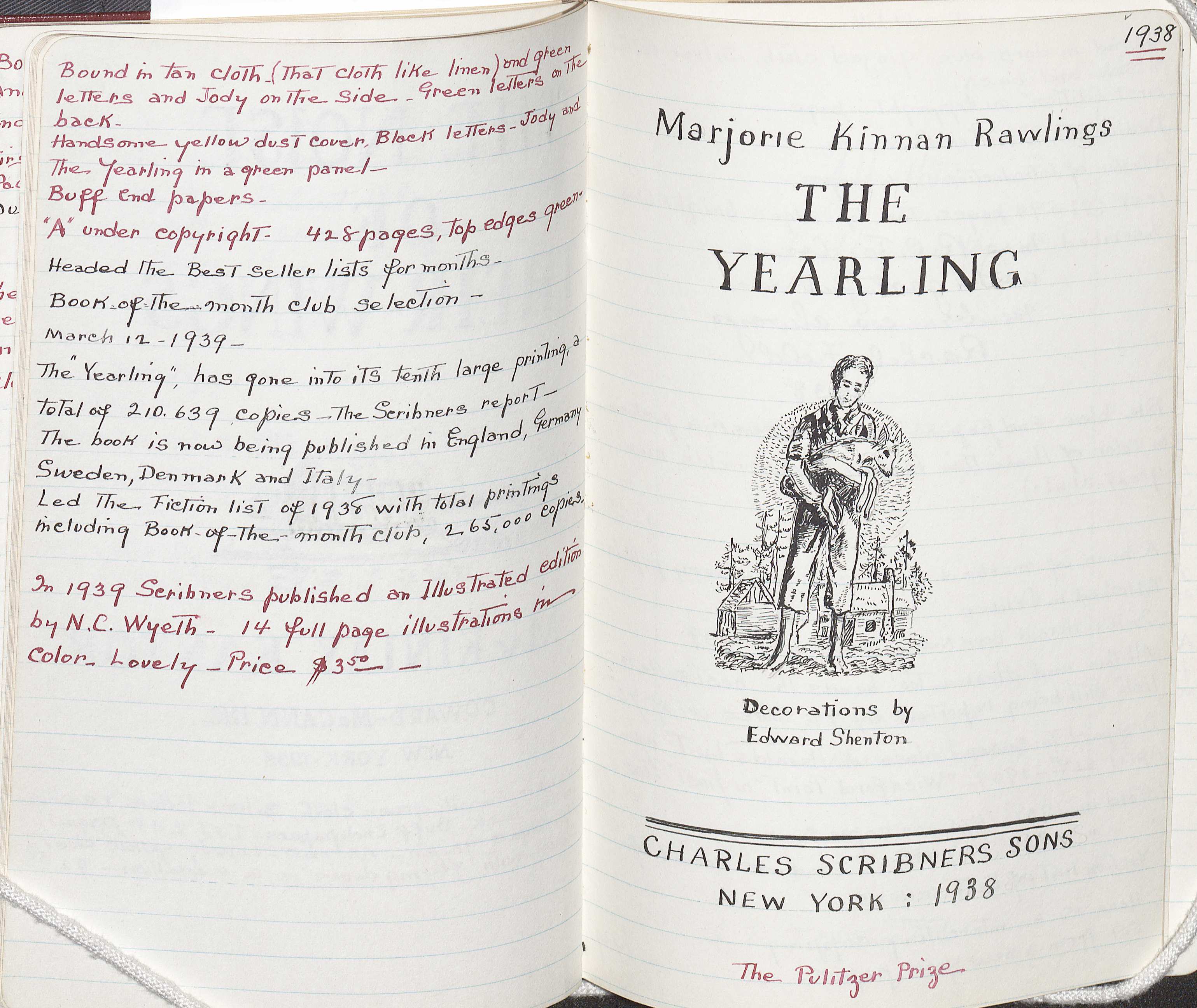

Catalog of Books In the Taylor Library of American Best Sellers. Lillian Gary Taylor records the title page of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ The Yearling as well as other information about the book, including its price and physical description. The Yearling was published in 1938 and won Rawlings a Pulitzer Prize in 1939. The novel was also the best selling book of 1938 and sold over 250,000 copies in that year alone. The popularity of this book was so great that it has been translated in over 20 different languages and also made into a motion picture in 1946. The novel describes the relationship between a young boy, named Jody, and his pet fawn, Flag. Like Rawlings’ other books, The Yearling is set in the inland of Florida where nature plays a key role in shaping the story. (MSS 5231-b. Taylor Collection of American Best-Sellers. Image by Petrina Jackson)

***

Adam Hawes, First-Year Student

Adam Hawes introduces himself at Tales From Under Grounds, November 19, 2013. (Photograph by Sanjay Suchak.)

The Raven Society

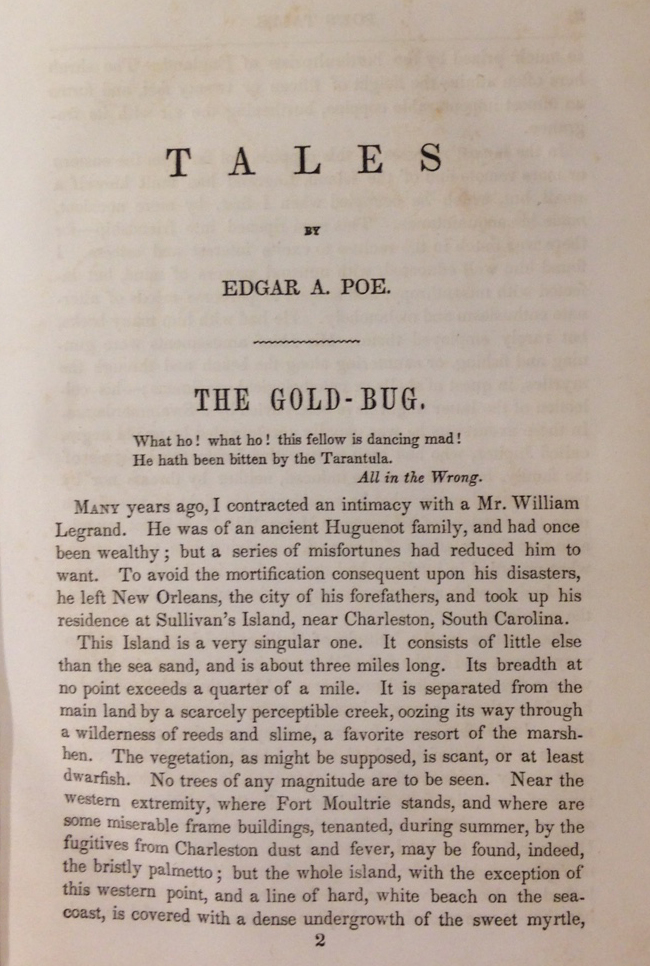

Edgar Allan Poe is perhaps the most well-known Gothic author of the 19th-century. His mysterious tales are some of the most recognized works in literature. Poe is probably also the most famous college dropout in the history of the University of Virginia. He only attended the university for one year before gambling debts forced him out. Despite only attending U.Va. for one year, Poe’s influence can still be felt here in the form of the Raven Society.

Named for Poe’s best-known poem, The Raven Society has been at U.Va. since 1904 when it was established as a merit-based, social, literary society. The society continues to hold academic integrity at a high value and presents awards to students and faculty for their academic interests and pursuits. The Raven Society also presents scholarships for undergraduate and graduate students at each school of the university. In addition to awarding academic achievement, the society has worked since 1907 to restore and upkeep Poe’s room on the West Range. Overall, the society keeps Poe’s spirit alive at the University of Virginia.

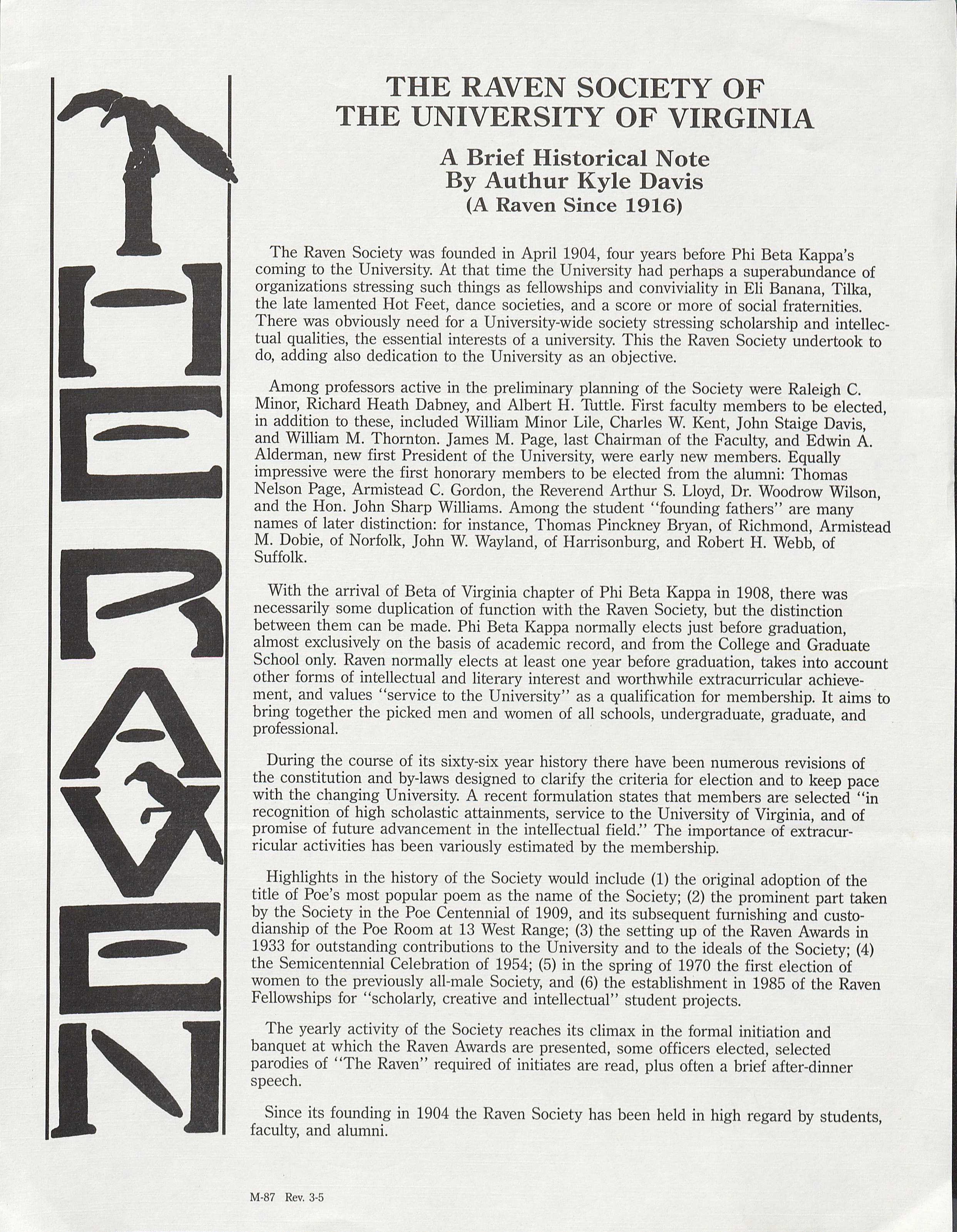

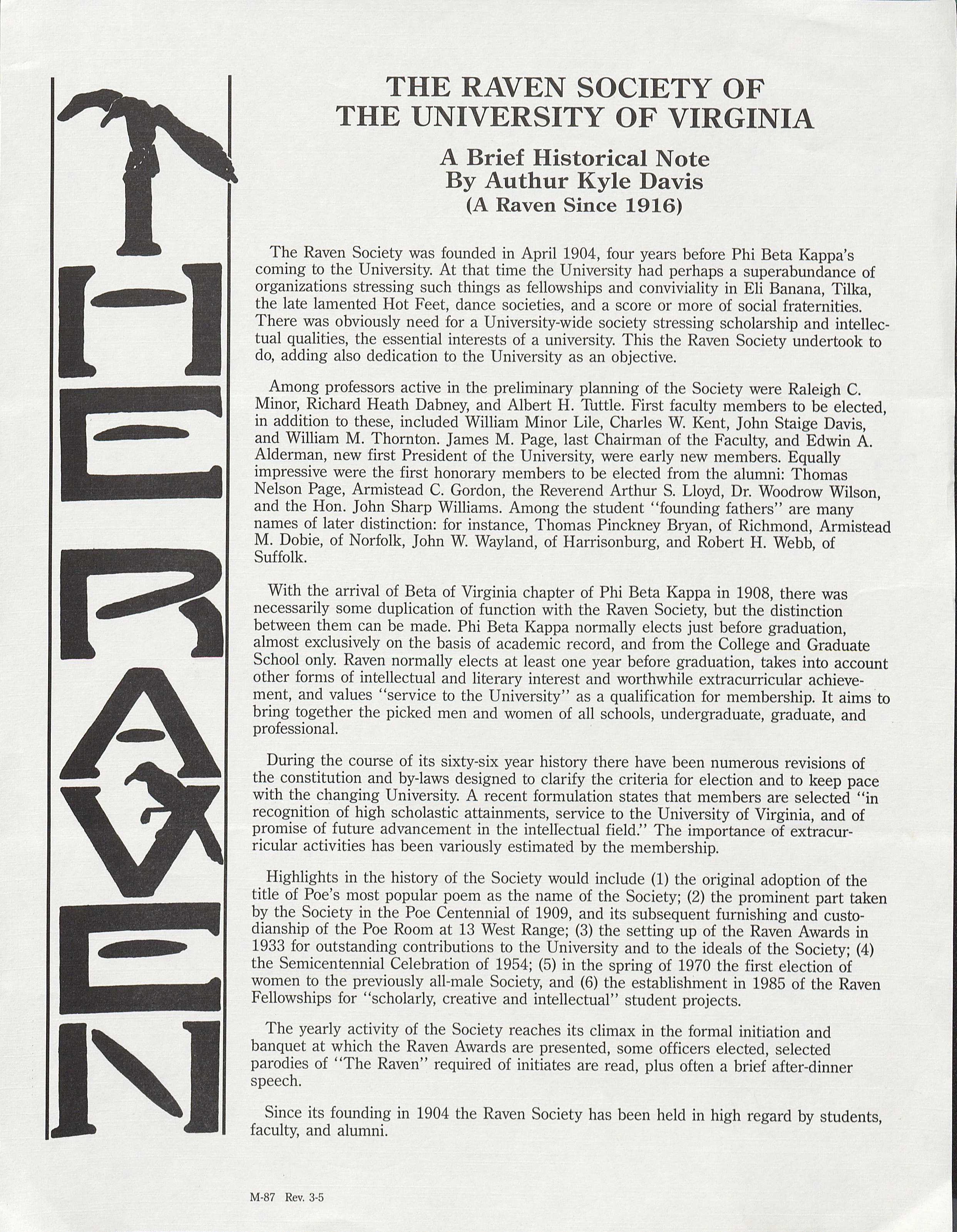

The Raven Society of the University of Virginia: A Brief Historical Note by Authur Kyle Davis, 1987. This broadside serves as an overview of the Raven Society. Printed over 80 years after the founding of the society, it lists the history of the society as well as the many aspects of the organization. It also explains membership requirements as well as the the purpose of the society. This document is from the papers of Francis L. Berkeley, Jr. (Broadside 1987 .D38. Image by Petrina Jackson)

This photograph shows the Raven Society at their annual Raven Awards Ceremony, 1952. At this ceremony, the Society presents the annual Raven Award to students, faculty, administrators, and alumni, recognizing them for their scholarly pursuits. The members can be seen here dressed formally. (RG-30/1/10.001. University of Virginia Visual History Collection. Image by Digitization Services)

***

Carrie Zettler, Second-Year Student

Carrie Zettler discusses her exhibit with library staff member Barbara Hatcher. (Photograph by Sanjay Suchak.)

The Hot Feet In Hot Water

The Hot Foot Society was formed in the spring of 1902 by a group of U.Va. students living on the East Range. The stated purpose of the organization was to host large parties that were open to all who wished to partake in the revelry. Unstated was the acknowledgement that members of the Hot Foot Society liked to drink. Never intending to be members of a secret society, Hot Feet often publicly displayed their drunkenness to the dismay of the University’s faculty.

In 1911, the Hot Foot Society pulled a bold prank. After a particularly rambunctious celebration, a few Hot Feet broke into the natural history exhibit in Cabell Hall and extracted stuffed animal specimens. President Alderman did not see the humor in the prank. He expelled four Hot Foot Society members and effectively disbanded the organization. In January 1913, the Incarnate Memories Prevail (I.M.P.) Society was formed. With the motto of “Nos Mortous, Sed Dormiens” (not dead, but sleeping), the legacy of the Hot Foot Society was preserved in this new organization.

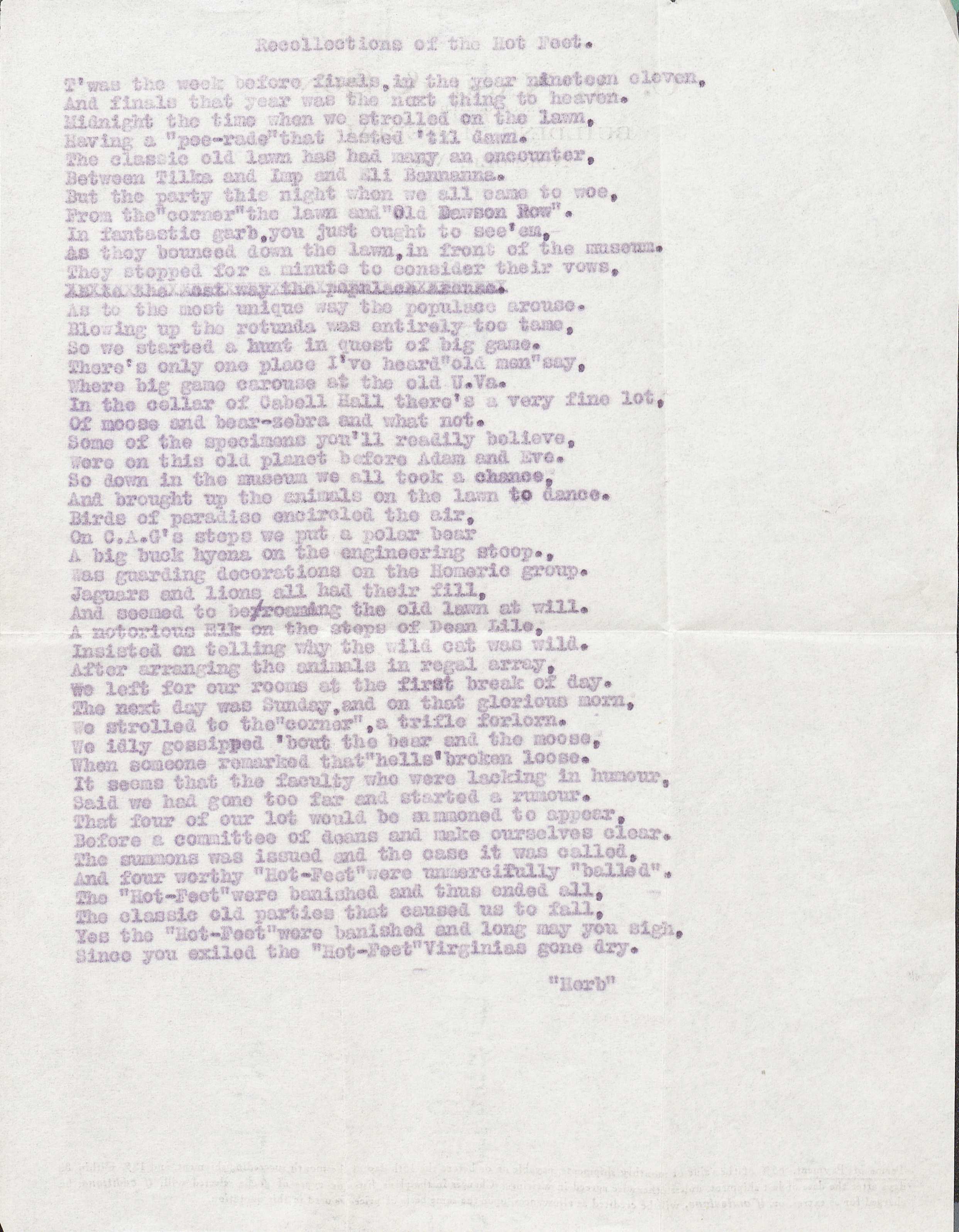

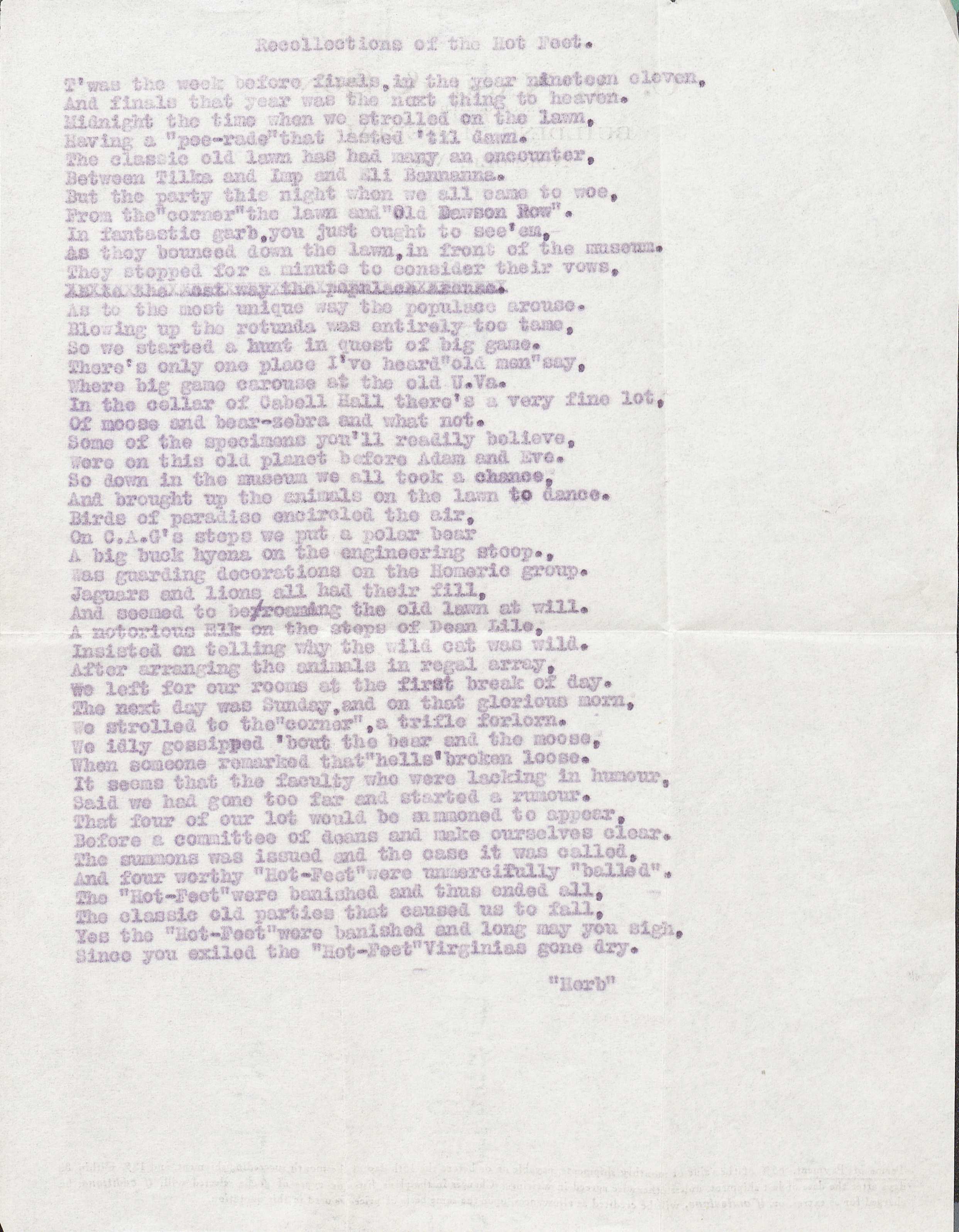

“Recollections of the Hot Feet.” Papers of the Hot Foot Society, 1903-1973, n.d. Written by Hot Foot Society member Herbert “Herb” Nash, “Recollections of the Hot Feet” is a poem that tells about the notorious prank pulled by the Hot Foot Society, circa May 1911. The incident happened after a celebration on the Lawn attended by members of Tilka, Eli Banana, and the Hot Foot Society. The poem recounts how a few Hot Feet broke into Cabell Hall and removed stuffed animal specimens from the natural history exhibit. They placed these animals, including a polar bear, a Bengal tiger, and an ostrich behind the desks of professors and on the steps of their Lawn residencies. The poem also alludes to the expulsion of four Hot Feet and the banishment of the organization. (RG-23/46/1.971. University of Virginia Archives. Image by Petrina Jackson)

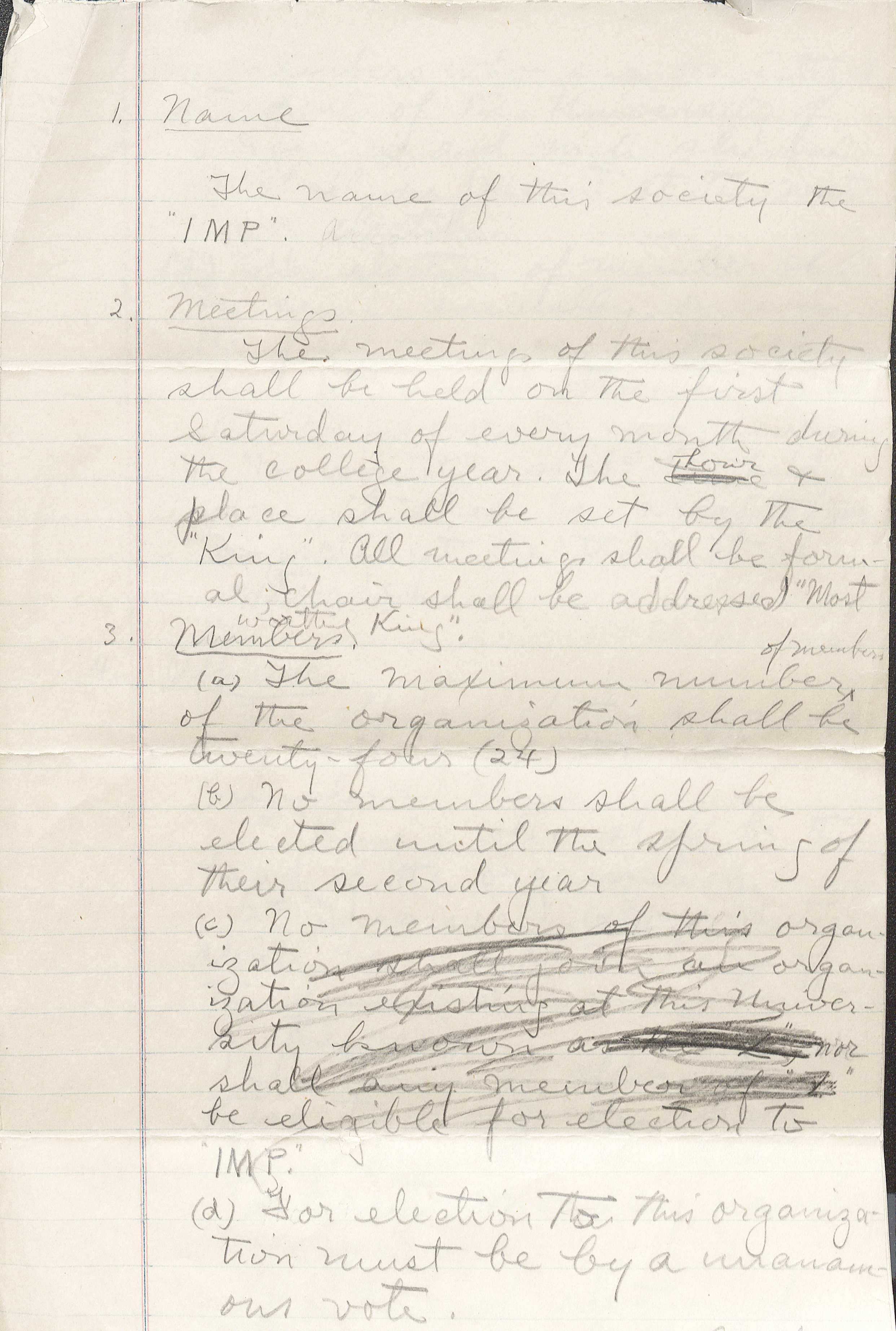

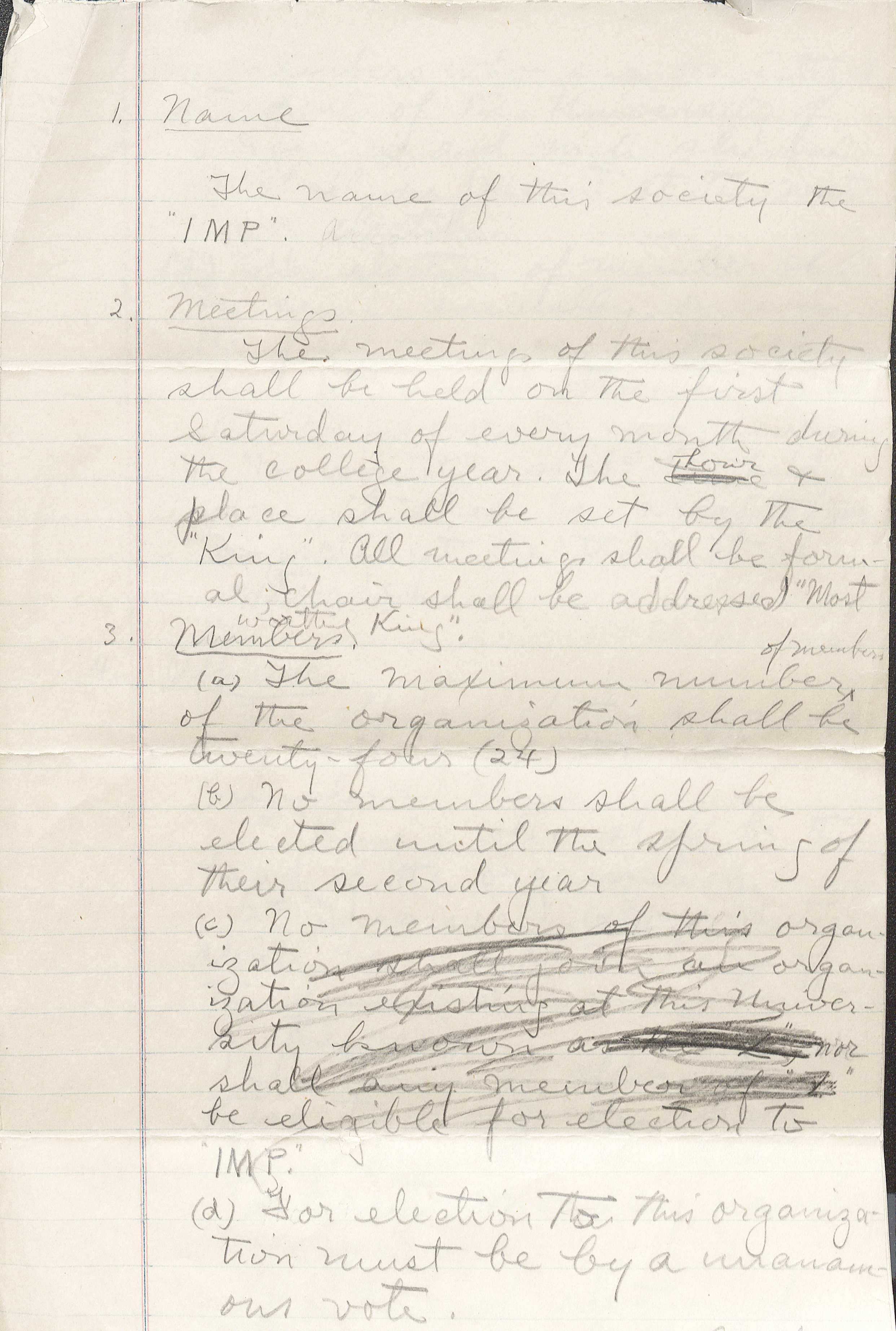

Charter of the I.M.P. Society from Papers of the Hot Foot Society, 1903-1973, c.a. 1914. This document is the first charter of the I.M.P. Society, which was founded on January 12, 1913. Written by Mc-K-Ski I, the charter was officially enacted a year later. The papers contain information about how the new organization would function. Details are provided about the I.M.P. Society’s meetings, members, fees and assessments, initiation, insignia, and festivities.(RG-23/46/1.971. University of Virginia Archives. Image by Petrina Jackson)