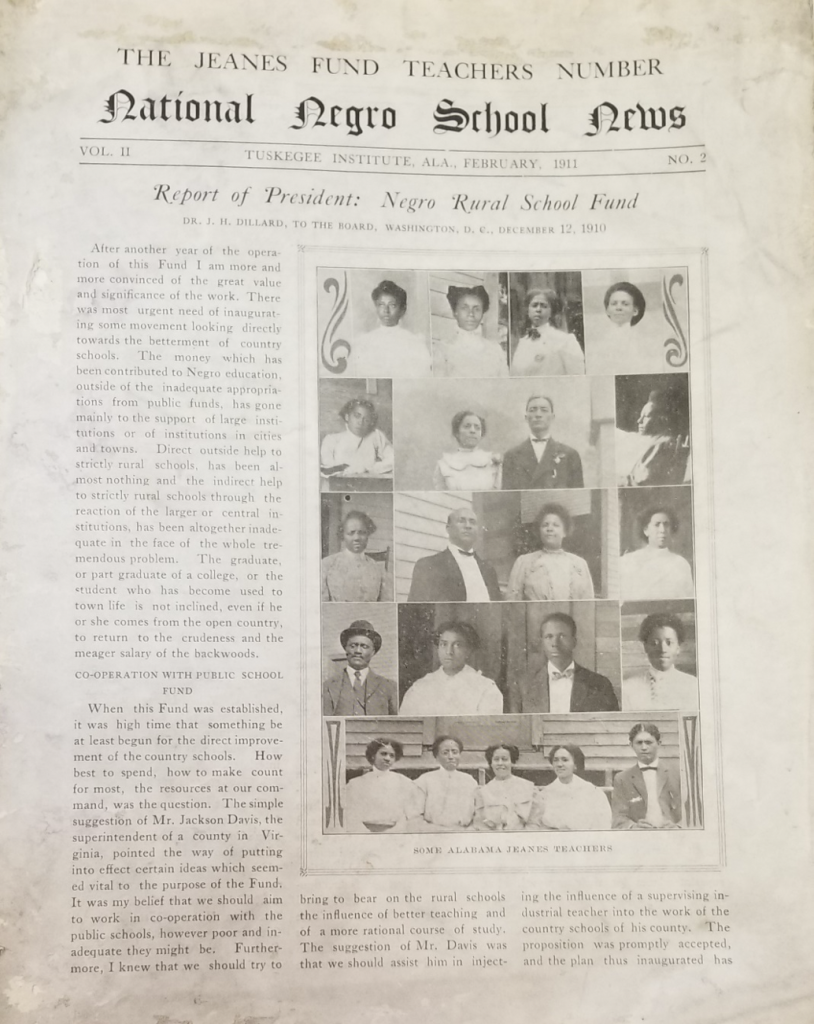

This post, in celebration of Black History Month, is contributed by Archives and Manuscripts Processor Ellen Welch in the Small Special Collections Library:

While processing a new collection—the Papers of Dr. Allison Burnett (MSS 16656), a biology professor and civil rights activist at the University of Virginia in the 1950s—I found a folder full of one to two page petitions signed by UVA faculty, staff, and students encouraging the boycott of the University Theater and other Charlottesville Businesses that denied admittance to Black students, faculty, and community members. The petitions piqued my interest and sent me on a journey where I caught a glimpse of what it might be like to be a Black student at UVA in the 1950s and 1960s, during the early years of desegregation. My encounter with this collection made me want to amplify the lived experiences documented in these papers and to highlight these students who endured so much pain at our University yet ultimately became successful in their careers.

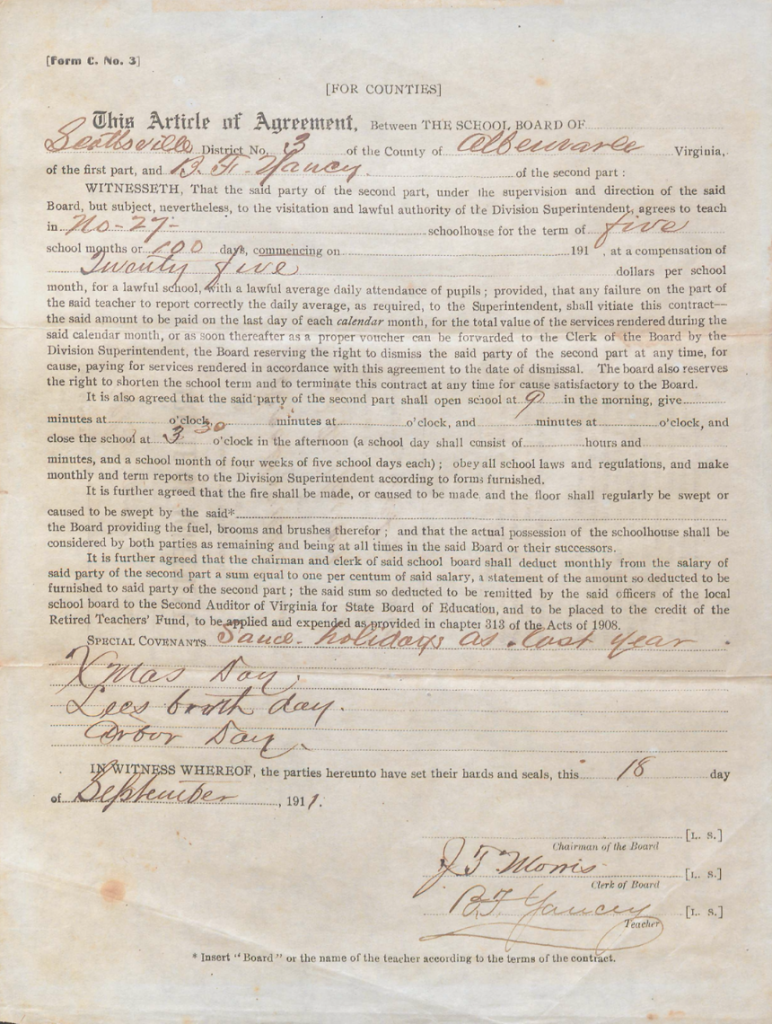

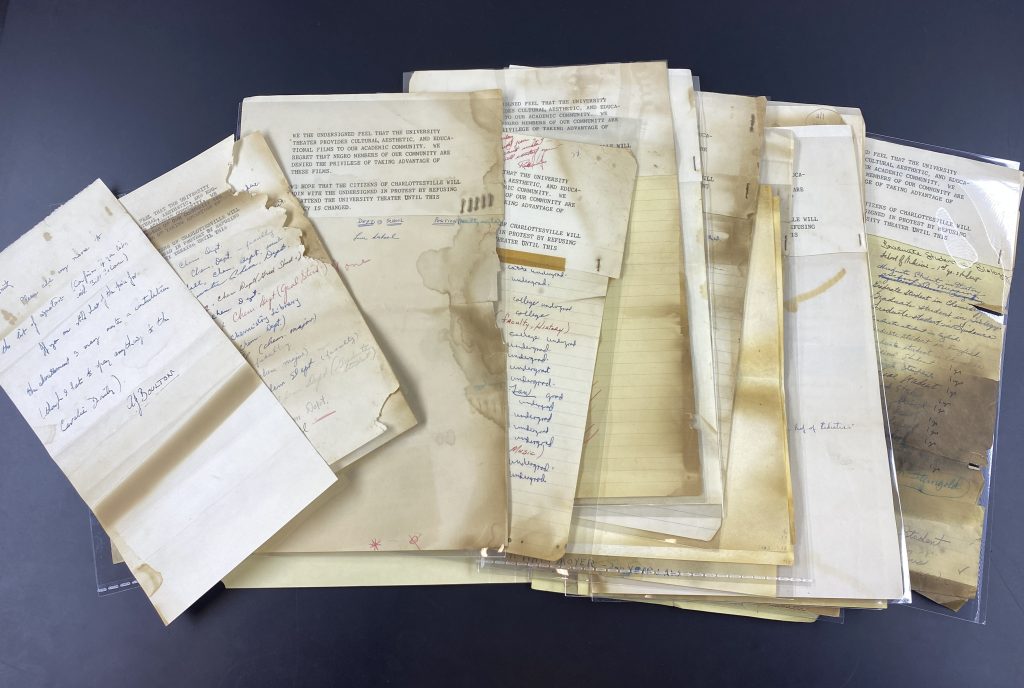

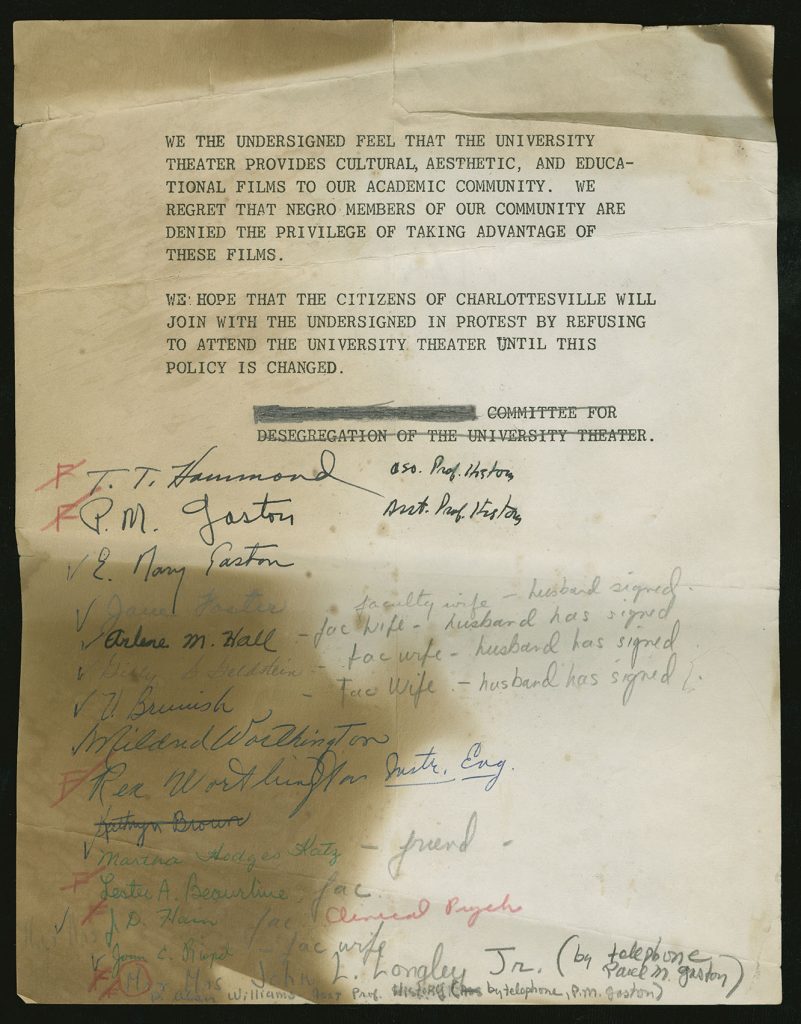

The folder of petitions from the Papers of Dr. Allison Burnett (MSS 16656) signed by UVA student and faculty and Charlottesville citizens pledging to boycott the University Theater.

Segregation, then Separate but Equal at UVA

In October 1959, Edgar F. Shannon became President of the University of Virginia following the retirement of President Colgate Darden. Darden’s administration presided over the University in the tumultuous years following the 1954 United States Supreme Court ruling against segregation in schools. As noted in Trailblazing Against Tradition: The Public History of Desegregation at the University of Virginia in 1955-75, Shannon’s administration “inherited and conformed to Darden’s fear that involvement and policies too clearly or loudly spoken would create sharp criticism and angry turbulence throughout the state and in turn it would arrest the growth of the University, while bringing them adverse publicity.”[1] According to local newspaper articles, President Darden supported an equal but separate “system of private education for the whites while maintaining schools for [Black students].”[2]

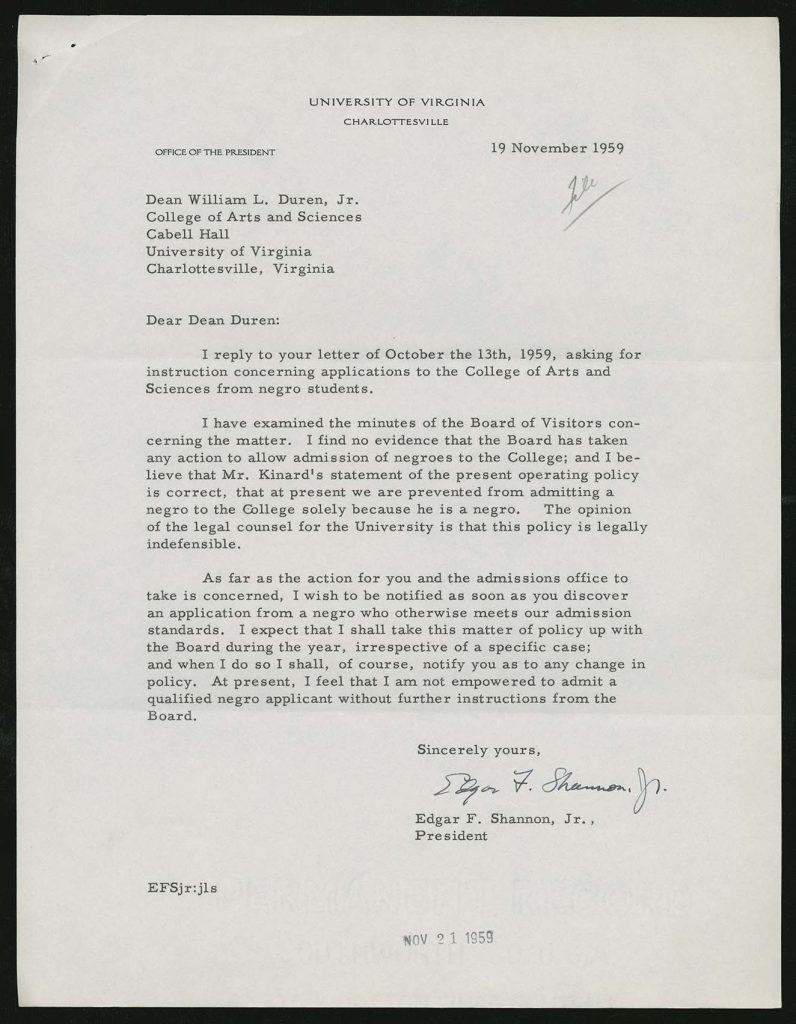

At first, Shannon—like Darden—did not support the activities of the civil rights movement at the University. In 1959, President Shannon corresponded with William L. Duren, Jr., Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, about the University admissions policy, explaining: “At present we are prevented from admitting a [Black student] to the College solely because he is a [Black student].”

He closed this letter, admitting, “I feel that I am not empowered to admit a qualified [Black student] without further instruction from the Board.”[3]

Letter from Edgar Shannon to Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences William Duren, November 19, 1959.

Integration at the University

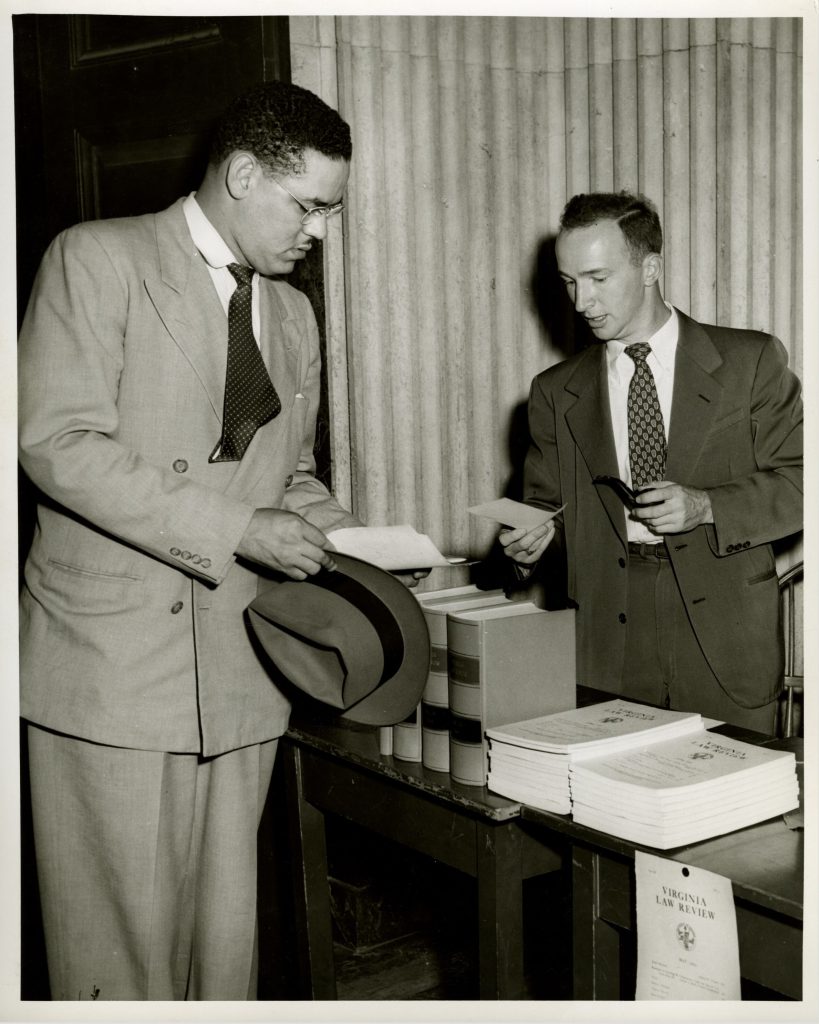

The University’s admissions policy made it very difficult for Black students to attend any part of the University, especially the College of Arts and Sciences. Gregory Hayes Swanson LL. B, A.B., won a lawsuit against the University for admission and became the first Black student to attend UVA in 1950. As noted by Encyclopedia Virginia, although Swanson’s legal victory allowed him admittance to the law school, his time at the University was both separate and unequal:

“Swanson was not permitted to partake in all aspects of university life. He was barred from living on Grounds …and social activities were not open to him. When he wrote to university president Colgate Darden and asked if he could attend any of the “private” dance societies that were, in Swanson’s words, “an integral part of the activity of the University,” he was denied the right. Darden’s response was that the dance societies as well as other organizations were “private” and therefore open only to members. According to University of Virginia Research Archivist, Ervin L. Jordan Jr., Swanson left the school after completing only one year “due to … an overwhelming climate of racial hostility and harassment.”

Gregory H. Swanson consults with Assistant Law Dean Charles Woltz after registration at UVA on Sept. 15, 1950. University of Virginia Visual History Collection, Small Special Collections Library.

As Shannon’s term as president began in 1959 and 1960, Black students endured similar racial slurs and barriers that Swanson experienced a decade earlier. Some Black students left the University in frustration while others were determined to pursue change. Our look at the University Theatre petition highlights the activism of three Black students:

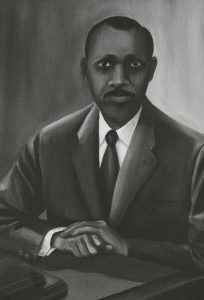

Amos Leroy “Roy” Willis challenged the University’s policy and was quietly admitted into the College of Arts in Sciences in 1960; he also was the first Black student to live on the Lawn (1961-62). He graduated with a B.S. in Chemistry from the University of Virginia and an MBA from Harvard University. He is currently the CEO of Roy Willis and Associates Inc., a California-based real estate development consulting firm that is deeply intertwined with social justice programs.

Dr. Wesley L. Harris (1941-present) graduated from the University of Virginia in 1964 with a bachelor’s degree in Aerospace Engineering. He was the first man—Black or white—to complete the newly established Engineering Honors Program; the first Black student to join the Jefferson Literary & Debating Society; and the second Black student to live on the Lawn in 1964. Following UVA, Harris attended Princeton University, graduating with a master’s degree in Aerospace and Mechanical Sciences in 1966, and completed a doctorate in 1968. He is an American physicist currently the C.S. Draper Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and has been awarded honorary doctorates by Milwaukee School of Engineering, Lane College and Old Dominion University.

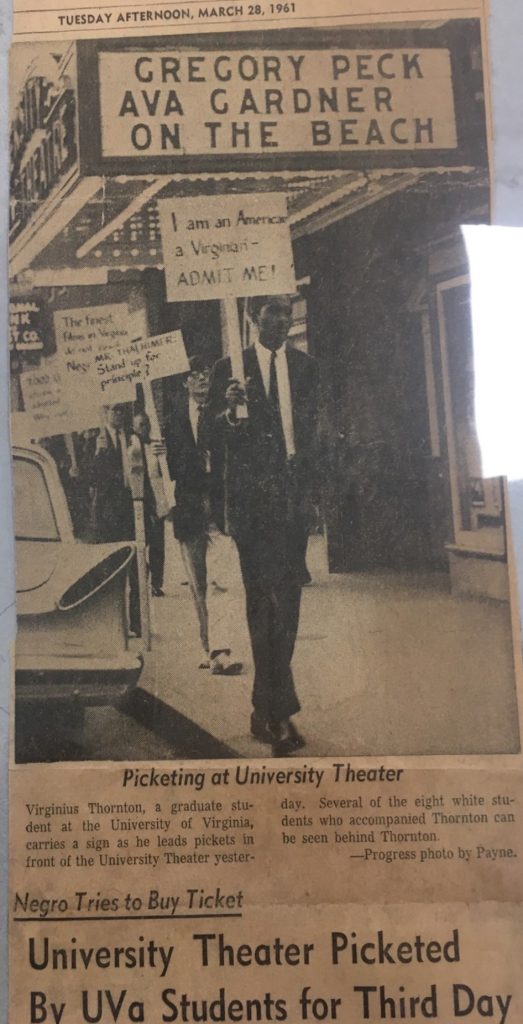

Dr. Virginius Bray Thornton III (1934-2015) was the first Black graduate student to enroll in a doctoral program in History at the University; he was also a civil rights leader who, in 1960 led 140 students in a sit-down strike at the segregated Petersburg Public Library and, in 1961, led the protest at UVA’s University Theater. Dr. Thornton was a professor for over 30 years at the Massachusetts Bay Community College where he taught American, Black, and Women’s History.

Dr. Virginius Bray Thornton III (1934-2015) was the first Black graduate student to enroll in a doctoral program in History at the University; he was also a civil rights leader who, in 1960 led 140 students in a sit-down strike at the segregated Petersburg Public Library and, in 1961, led the protest at UVA’s University Theater. Dr. Thornton was a professor for over 30 years at the Massachusetts Bay Community College where he taught American, Black, and Women’s History.

Student Activists

Willis, Harris, and Thornton were active in the Charlottesville Albemarle Virginia Council on Human Relations, which promoted interracial equality in Charlottesville and the University. Harris was Council chair and invited Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to speak at Old Cabell Hall to an audience of 900 people in 1963. As activists both at the University and in the Charlottesville community, they picketed local establishments including the University Theater, Buddy’s Restaurant, and the Holiday Inn because these businesses refused to admit Black people.

The 1961 incident that prompted petitions urging the Boycott of UVA’s University Theatre are documented in Thomas M. Hanna’s 2007 thesis: “Shut It Down, Open It Up: A History of the New Left at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville”:

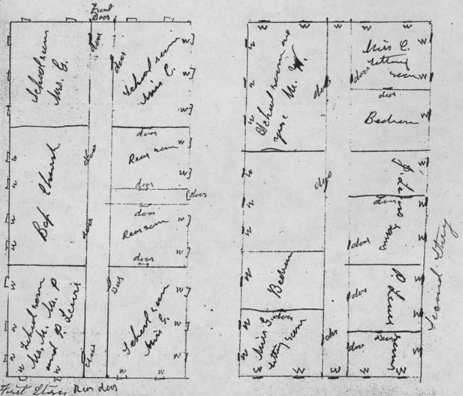

“On March 1, 1961, four black students, supported by twenty-five white students, faculty members, including Dr. Allison L. Burnett, an assistant professor of biology, attempted to buy tickets from the University Theatre. They were denied entrance by theatre manager, John W. Kase, who told the group that he could not admit them under state law because the theatre had no balcony to allow for segregation.”

Petitions signed by UVA faculty committing to boycott the University Theater for refusing to admit Black students in March 1961. The first two signatures on the petition are from Thomas T. Hammond and Paul M. Gaston, long-serving UVA History professors and civil rights activists in Charlottesville.

The attempted integration of the theatre outraged the editor-in-chief Junius R. Fishburne of the University of Virginia student newspaper, The Cavalier Daily. Fishburne unwisely used his editorial power to attack the activists and their attempts to integrate the theatre; according to “Shut It Down, Open It Up,” the editorial only publicized the incident and prompted an inundation of letters for and against segregation:

“The student-faculty group began a petition calling for a boycott of the University Theatre until it opened its doors to Black students. Spurred on by Burnett, the petition garnered over 600 signatures by April 14 and was headed by Professor Dumas Malone, the Thomas Jefferson Scholar at the University. The petition was even sent to United States Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, an alumnus of the university law school, for his signature, but it is unclear if he ever received or responded to it.”

The campaign to integrate the Theatre languished as its management refused the activists’ demand and student interest in the boycott declined. Concerned students and faculty members turned to the University for recognition of the Jefferson Chapter of the Virginia Council on Human Relations. During the next two years, these activists joined with the city to begin a campaign for comprehensive desegregation of Charlottesville’s businesses and public accommodations.

UVA Faculty Activists: Paul M. Gaston and Thomas Taylor Hammond

The petition against the University theater was signed by Paul M. Gaston, a Professor of History at the University of Virginia for 40 years (1957-1997), who studied the history of the American South as well as American Civil Rights. As a former President of the Southern Regional Council, he was well known in the Charlottesville area during the 1960s for his Civil Rights activism. Born in Fairhope, Alabama, he arrived in Charlottesville in the fall of 1957 as a junior instructor of history at UVA. He was involved in several demonstrations, most famously the 1963 sit-ins at Buddy’s Restaurant, which is remembered as one of the pivotal events leading to the desegregation of the Charlottesville area. Gaston published several books and articles on Civil Rights and affirmative action, as well as the history of the United States South. He died on June 14, 2019.

The petition against the University Theater was also signed by Thomas Taylor Hammond (1920-1993), a distinguished professor of history emeritus of the University of Virginia (1949-1991), who specialized in Russian and Slavic studies and was an active civil rights advocate. Encouraged by University of Virginia scholar, Dumas Malone, Hammond took the teaching position at the University of Virginia and for a period of 42 years, taught courses on Soviet history and Soviet foreign policy. According to the Papers of Thomas T. Hammond finding aid, “Hammond was a force for advancing racial integration” during the civil rights period in the 1950’s and 1960’s in Charlottesville, Virginia.”

With Paul Gaston, Hammond founded the Martin Luther King Chapter of the Council on Human Relations to recruit Black students and faculty and to eliminate discrimination. Hammond also served as president of the Charlottesville Chapter of the Council on Human Relations and as a member of the Executive Committee of the local branch of the NAACP, promoting social justice in local schools, parks, and other facilities. Thomas Hammond died on February 11, 1993.

Citations:

[1] http://xroads.virginia.edu/~ug03/omara-alwala/Harrison/uvasixties.html

[2] President Papers (RG-2/1/2.641). Subseries 1 Box 15. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia

[3] President Papers (RG-2/1/2.641). Subseries 1 Box 5. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia

Additional Sources:

Papers of Dr. Allison Burnett Civil Rights (MSS 16656). Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia Library.

President Papers RG-2/1/2.641 Subseries 1 Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library University of Virginia.

Hanna, Thomas M. “Shut It Down, Open It Up: A History of the New Left at the

University of Virginia, Charlottesville” Thesis Virginia Commonwealth University 2007

“An Epoch of Change. A Timeline of the University 1955-1975. The Sixties”

“The Road to Desegregation: The University in the 1960’s” Jackson, NAACP, and Swanson.

Addison, Dan “First on the Lawn: University Honors Roy Willis” Virginia Magazine, University of Virginia Alumni Association.

“Wesley L. Harris” Wikipedia.

“Paul M. Gaston.” Wikipedia.

“In Memoriam: Historian Paul Gaston, Early Civil Rights Activist” UVA Today. June 18, 2019

A Guide to the papers of Thomas T. Hammond. Virginia Heritage.

“Thomas Taylor Hammond” Wikidata.

![Segregation, then Separate but Equal at UVA In October 1959, Edgar F. Shannon became President of the University of Virginia following the retirement of President Colgate Darden. Darden’s administration presided over the University in the tumultuous years following the 1954 United States Supreme Court ruling against segregation in schools. As noted in Trailblazing Against Tradition: The Public History of Desegregation at the University of Virginia in 1955-75, Shannon’s administration “inherited and conformed to Darden’s fear that involvement and policies too clearly or loudly spoken would create sharp criticism and angry turbulence throughout the state and in turn it would arrest the growth of the University, while bringing them adverse publicity.” According to local newspaper articles, President Darden supported an equal but separate “system of private education for the whites while maintaining schools for [Black students].”](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/img20220223_11334469-180x300.jpg)