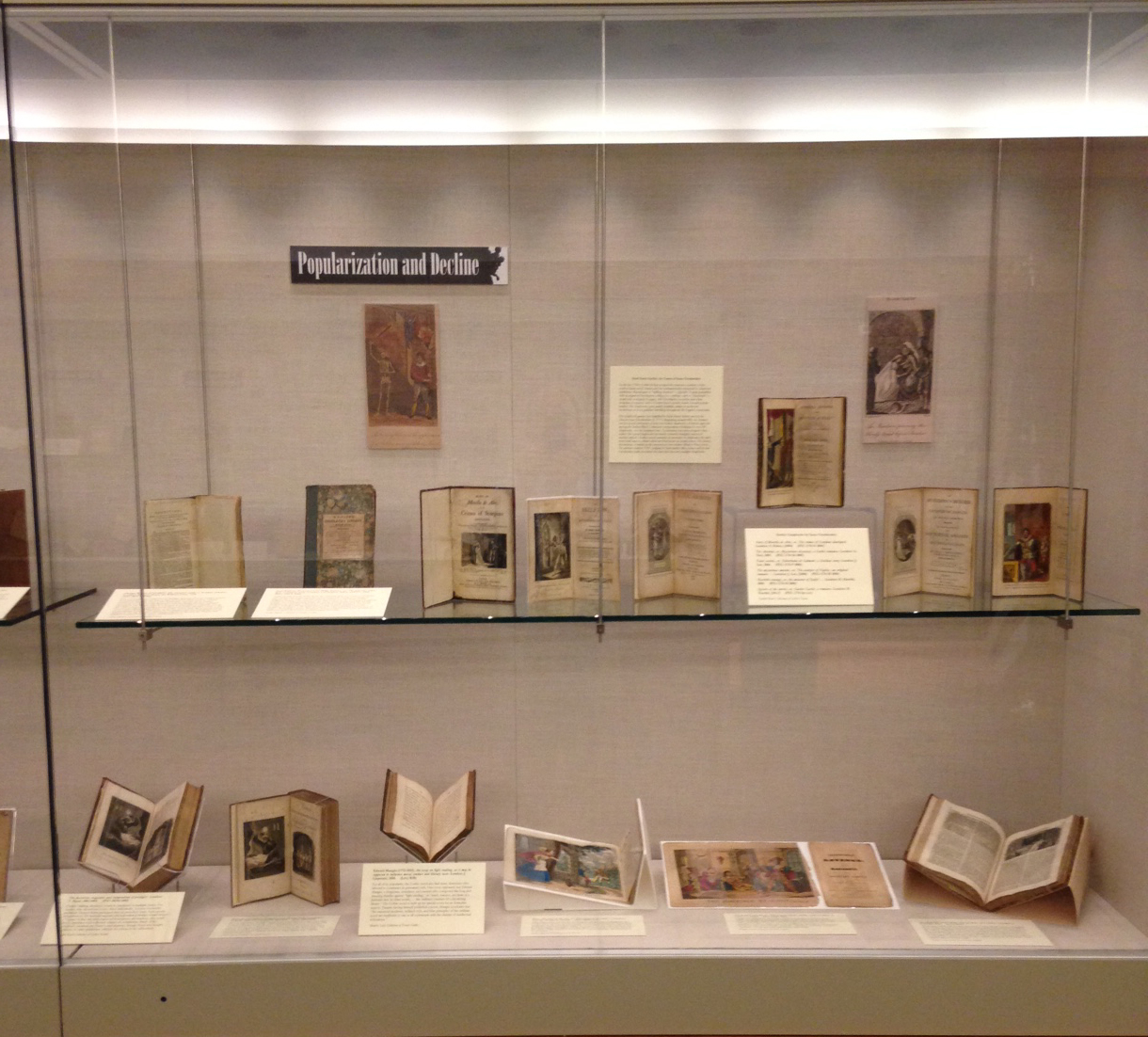

Our current exhibition at the Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library, Shakespeare by the Book, focuses on the history of Shakespeare as a book. As a result, the exhibition showcases mostly male editors and publishers until we reach the twentieth century. (Hannah Whitmore, our widow publisher of The Merchant of Venice, is a notable exception.) However, this is not to say that women were not involved in building Shakespeare in the early modern era. In fact, it is said that the first critical essay ever written on Shakespeare was by Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, in 1664. In the eighteenth century, a number of other female critics published works on Shakespeare, some of which are held here in the Small Library.

Elizabeth Montagu

Out rush’d a Female to protect the Bard,

Snatch’d up her Spear, and for the fight prepar’d:

Attack’d the Vet’ran, pierc’d his Sev’n-fold Shield,

And drove him wounded, fainting from the field.

With Laurel crown’d away the Goddess flew,

Pallas contest then open’d to our view,

Quitting her fav’rite form of Montagu.

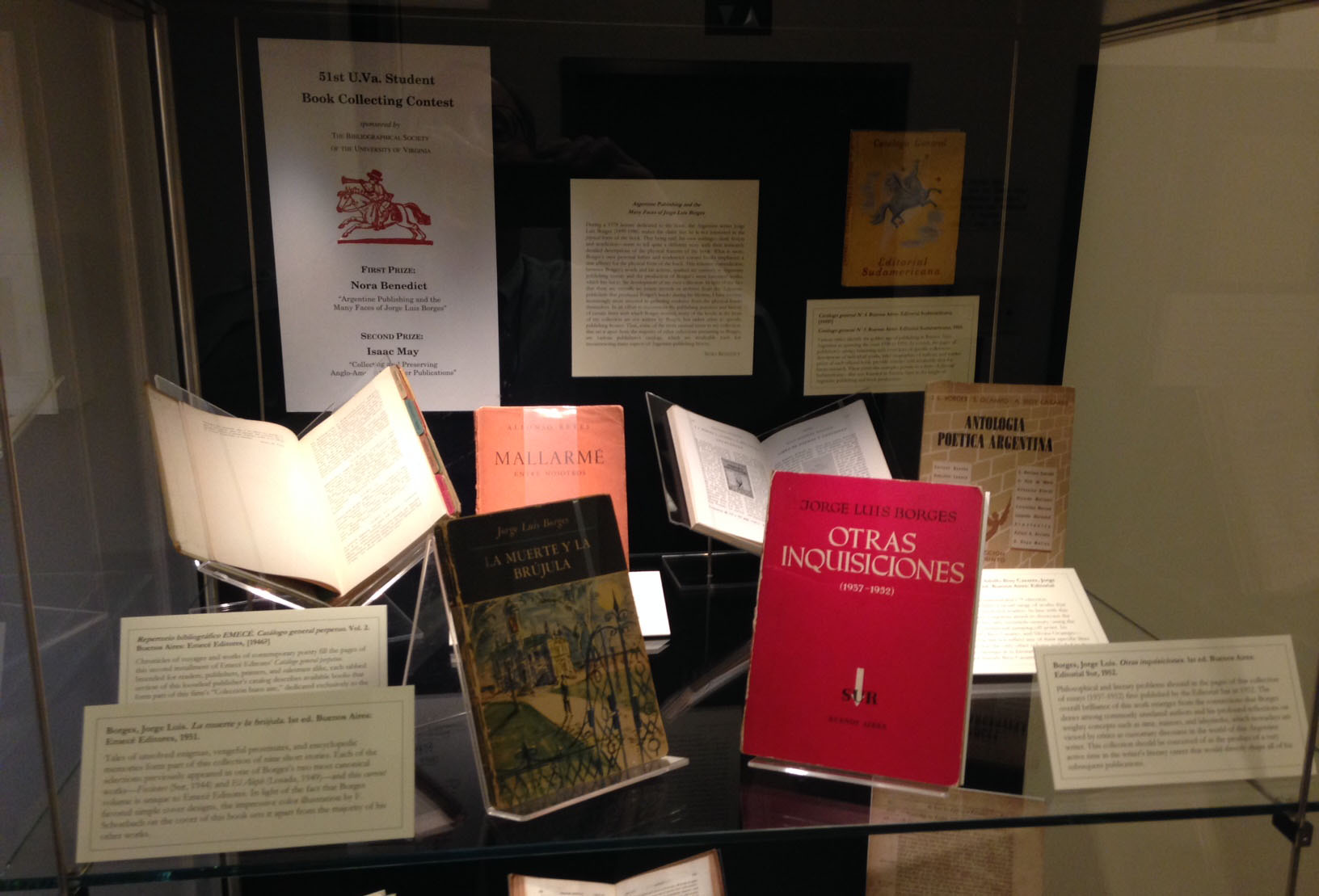

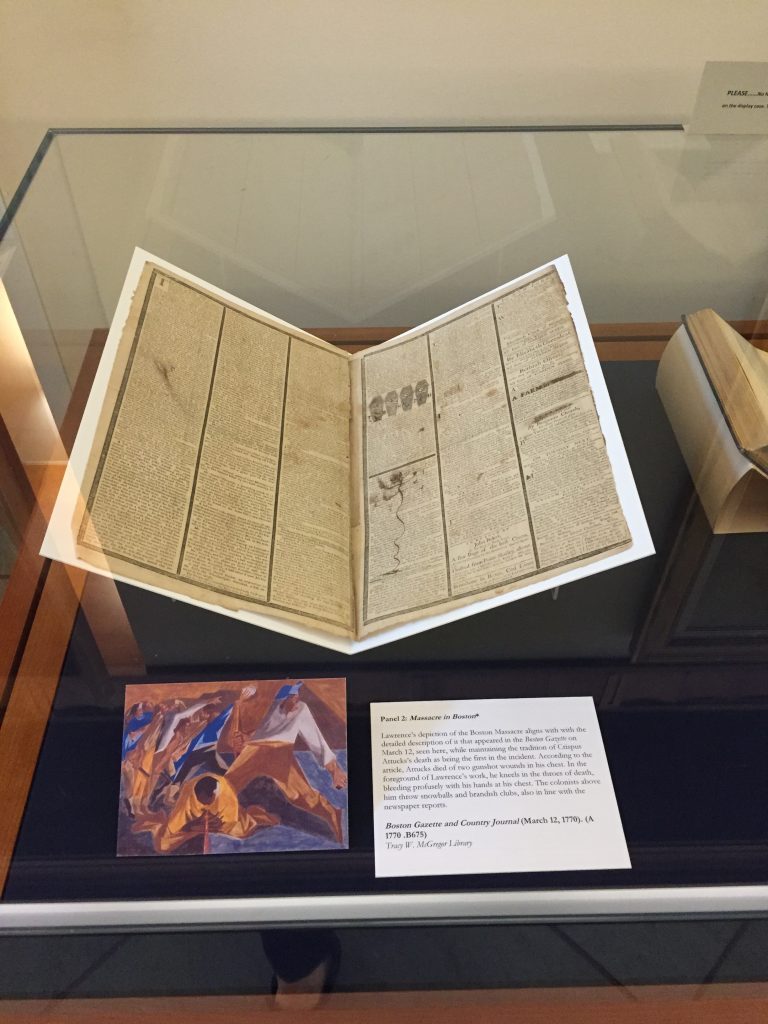

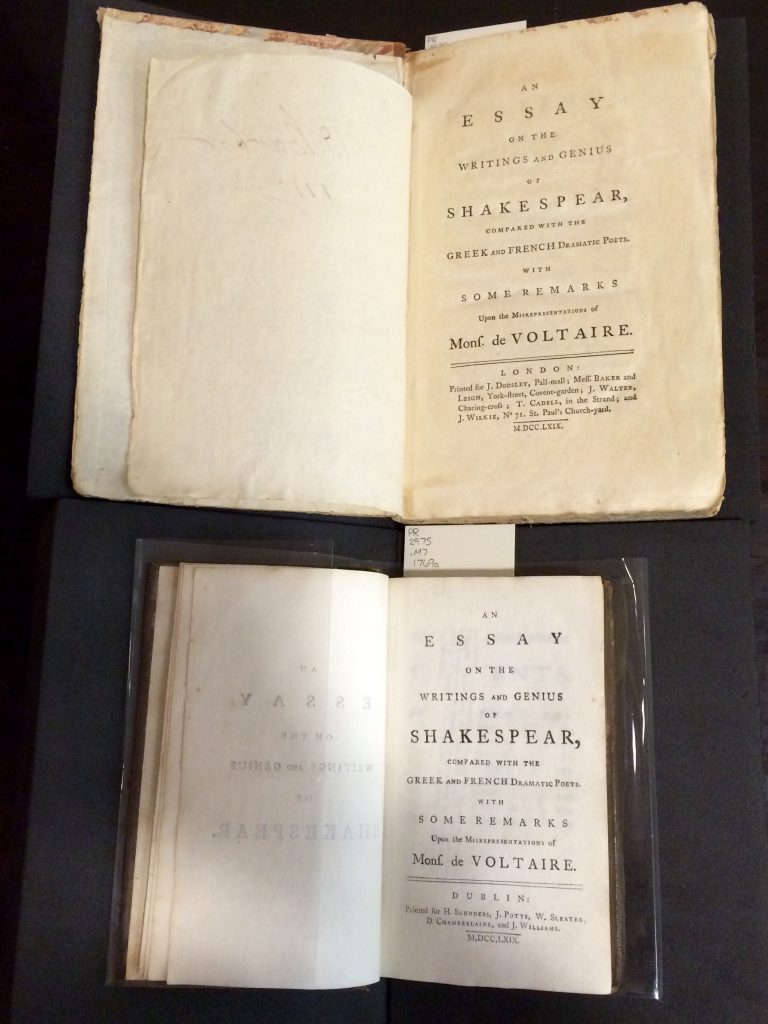

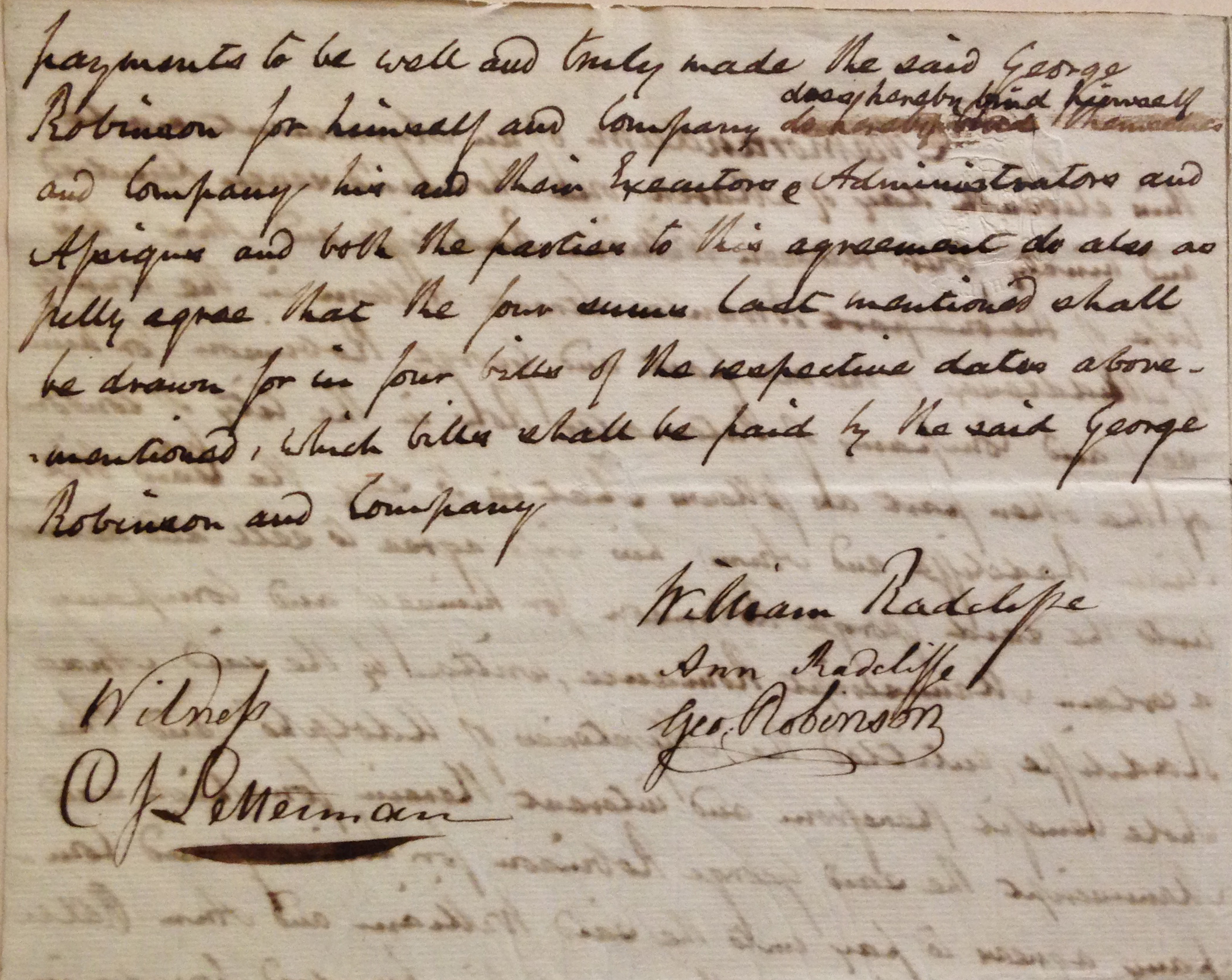

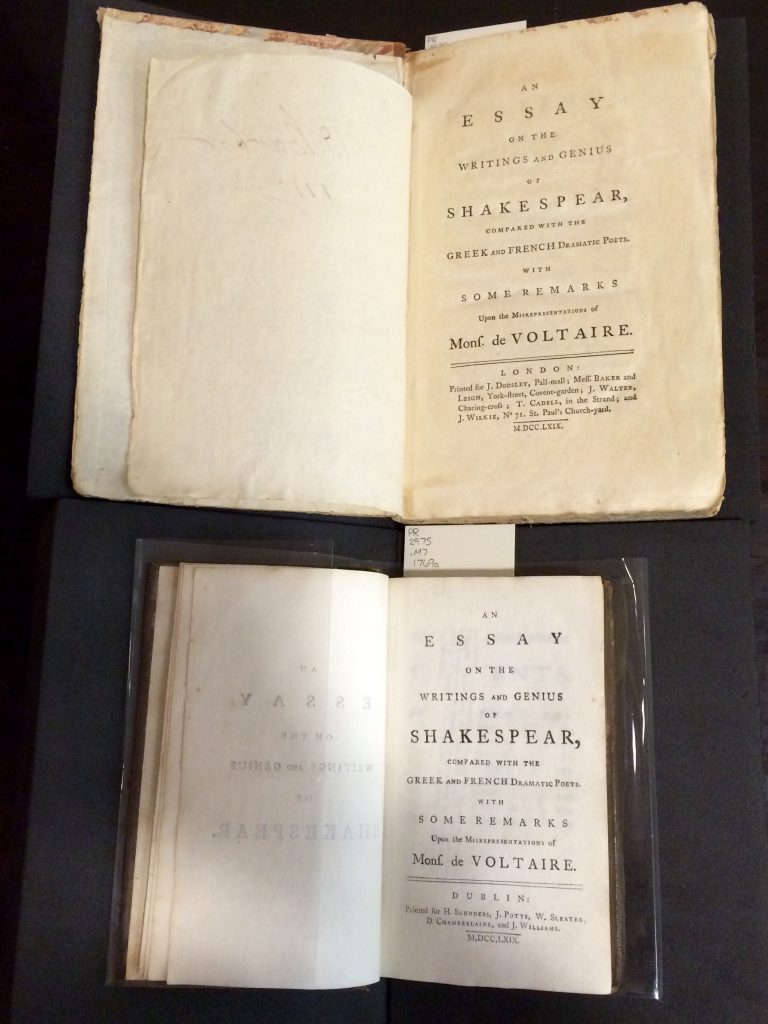

The stanza above is how David Garrick, famous Shakespearean actor, characterized Elizabeth Montagu on the occasion of the Shakespeare Jubilee in 1769, the same year that Montagu’s An Essay on the Writings and Genius of Shakespeare was published. Montagu is perhaps best known for being “Queen of the Bluestockings,” a group of women who held a literary salon where they engaged in “rational conversation.” Her essay on Shakespeare is an important moment in Shakespearean criticism. This Bluestocking had the audacity to “protect the Bard” from the famed French critic Voltaire, and from her good friend, Samuel Johnson, whose preface to his edition of Shakespeare (1765) she felt neglected Shakespeare’s genius. In her essay, Montagu emphasizes Shakespeare’s understanding of human nature and his genius despite his lack of education.

Montagu’s essay sold exceptionally well: it went through seven editions and was translated into French and Italian. Shown here are first English and Irish editions. (PR 2975 .M7 1769, PR 2975 .M7 1769a)

Significantly, Montagu calls the playwright “Our Shakespeare” almost immediately in her preface. What follows is an apotheosis of William Shakespeare. As if warring with all of France and not just Voltaire (whose terrible translations she ridicules), she defends Shakespeare for not following all the rules of classical drama, declaring that his plays are more natural for their irregularities than the artificial plays of the French. Additionally, she is one of the earlier critics to take his history plays seriously, arguing that they are excellent vehicles for moral instruction, which, in her view, is the aspiration of all drama. Unlike many of the male editors represented in our exhibition who tried to “fix” or find the “true” Shakespeare, Montagu understands that Shakespeare’s dramatic irregularities are what make him a genius.

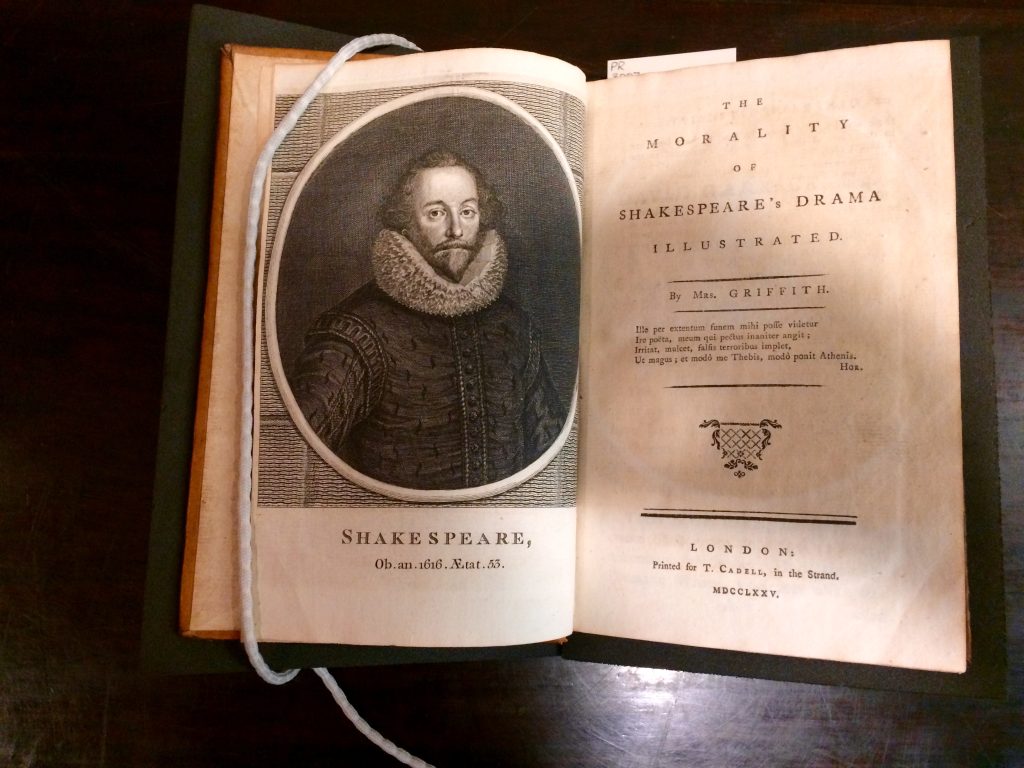

Elizabeth Griffith

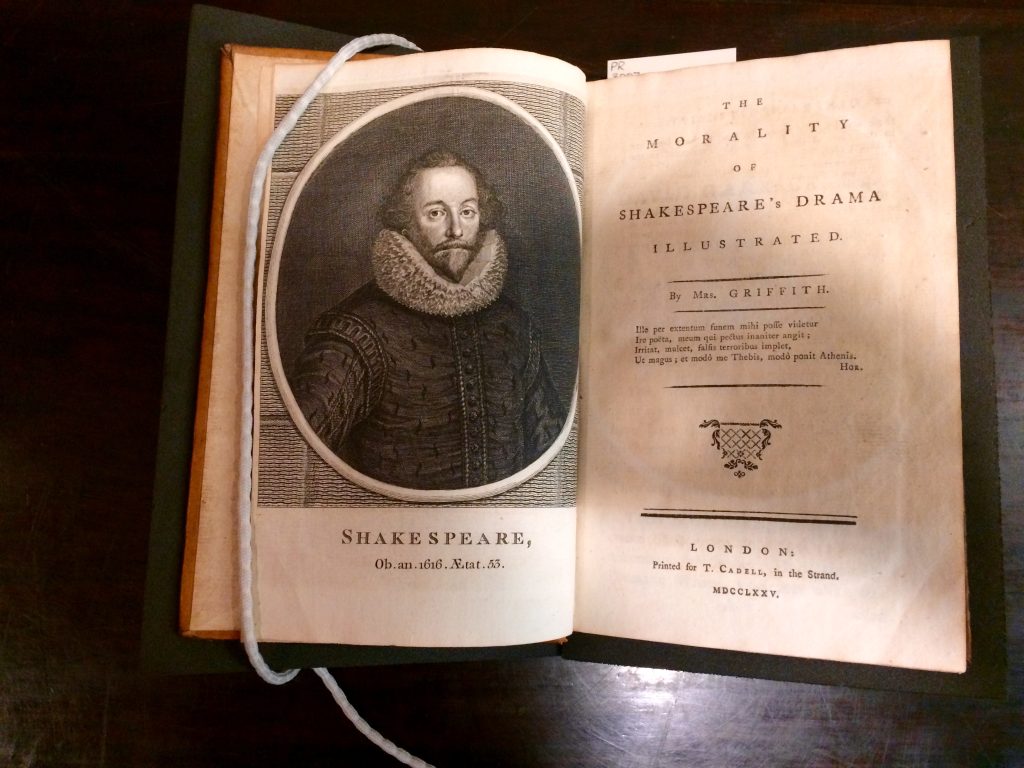

Another Elizabeth picked up the “spear” and rushed out to protect Shakespeare a few years later: Irish playwright, novelist, and actor Elizabeth Griffith. Griffith debuted on the stage as Juliet at Dublin’s Smock Alley theatre in 1749, eventually specializing in tragic roles like Cordelia and Ophelia. Inspired by Montagu’s work on Shakespeare’s genius, she set out to defend his morals in The Morality of Shakespeare’s Drama Illustrated (1775). Griffith wanted to illustrate a system of “social duties” that Johnson claimed could be culled from Shakespeare’s plays in his preface: “I have ventured to assume the task of placing his Ethic merits in a more conspicuous point of view, than they have ever hitherto been presented in to the Public.” She contends that Shakespeare’s plays are effective because the morals arise naturally out of the play’s action and his characters are so attuned to human nature that audiences promptly grasp the lesson.

Note that unlike Montagu’s Essay, Elizabeth Griffith’s title page lists her name. (PR 3007 .G7 1775)

Griffith’s emphasis on the naturalness of Shakespeare’s characters brings us to her radical reading of drama. Like Montagu, she also defends Shakespeare from Voltaire, who criticizes Shakespeare for breaking from the classical unities of time, place, and action. In response, Griffith invents a fourth unity: character. For her, Shakespeare’s consistency in character is more important than whether his plays take place in one day or in one place because character is what makes the plays, as well as morals, succeed. Griffith’s work, moreover, is radical in its own right: she is the first woman ever to emend Shakespeare’s plays. While her work is not an edition, she includes passages with her own textual alterations and she explains Shakespeare’s language in her own footnotes. When coupled with her popular plays and novels, it should come as no surprise that this work earned her a spot next to Elizabeth Montagu in the famed portrait, “The Nine Living Muses of Great Britain” (1779).

The Nine Living Muses of Great Britain by Richard Samuel, oil on canvas, 1778. Elizabeth Montagu is on the right, wearing a red cape with a cup in her hand. Elizabeth Griffith is seated on the right in white with a hand on her cheek. (NPG 4905: Image courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, Creative Commons Licence).

Our last Elizabeth is an author, playwright, and actor who was perhaps a little too outrageous to be considered one of the nine living muses of Great Britain, but she and Shakespeare have that moral condemnation in common. Elizabeth Simpson ran away from home at the age of nineteen to become an actor despite having a stammer and no place to go. After marrying fellow Catholic actor Joseph Inchbald, she eventually made her stage debut as Cordelia to her husband’s Lear in 1772. Not only did she continue to act in Shakespeare’s plays for some time (she acted in the production of

The Merchant of Venice represented in the Hannah Whitmore edition in our exhibition), she also began to write her own plays:

Lovers’ Vow features prominently in Jane Austen’s

Mansfield Park (1814)

. Yet today, she is best remembered for her novels, particularly

A Simple Story (1791).

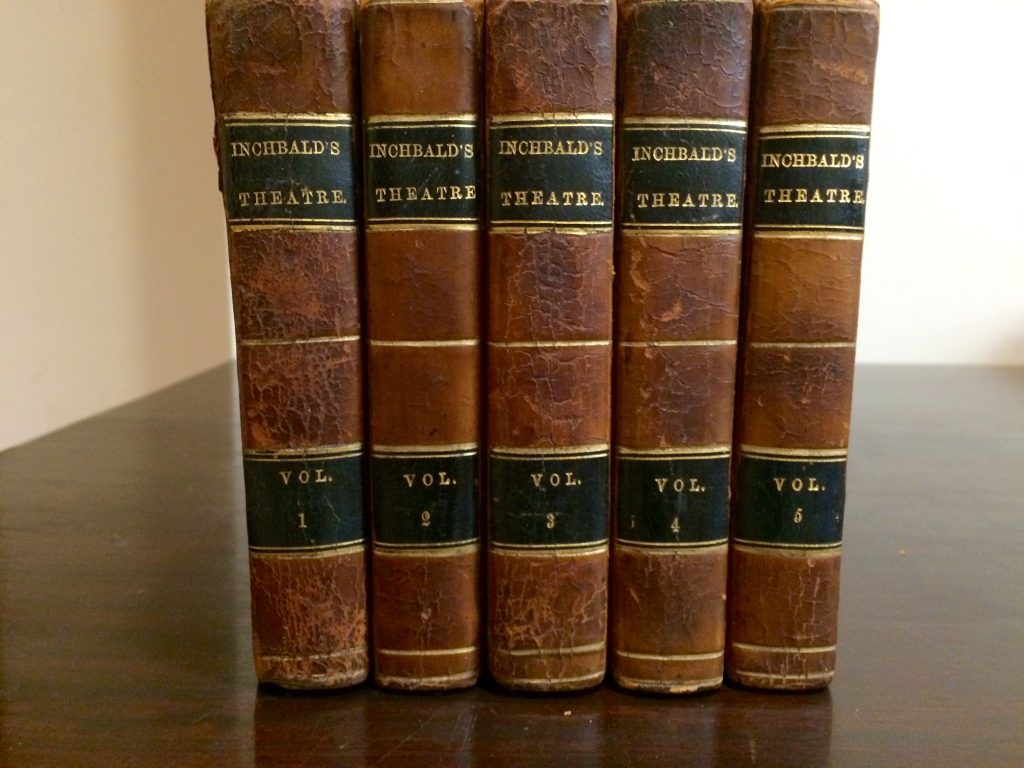

After her reputation was well established, publisher Joseph Longman asked Inchbald to write prefaces to The British Theatre, a collection of plays in twenty-five volumes, five volumes of which were Shakespeare’s plays (1806–1809). It is for this work that Inchbald has been labeled Britain’s first professional theater critic. Like Montagu and Griffith, she argues for Shakespeare’s morality in her prefaces, but notably she traces his morality and his realism to the way he mixes vice and virtue in some characters. In her analysis of Shakespeare’s morals, she also offers commentary on contemporary social mores, as in her preface to I Henry IV:

This is a play which all men admire , and which most women dislike. Many revolting expressions in the comic parts, much boisterous courage in some of the graver scenes, together with Falstaff’s unwieldy person, offend every female auditor; and whilst a facetious Prince of Wales is employed in taking purses on the highway, a lady would rather see him stealing hearts at a ball, though the event might produce more fatal consequences.

In addition to her hint about the problems of the sexual double standard here (“more fatal consequences”), we also see Shakespeare described in terms of performance (“auditor”). Inchbald’s prefaces are the first critical works to appreciate the theatrical as well as literary value of Shakespeare. She even criticizes some of her editorial predecessors for not addressing the role of performance and the pleasures we glean from Shakespeare’s language. Unlike the other Elizabeths, who mostly focused on morality and genius, Inchbald was condemned for daring to be a female critic: as her male biographer, James Boaden, wrote, “there is something unfeminine, too, in a lady’s placing herself in the seat of judgment” (1833).

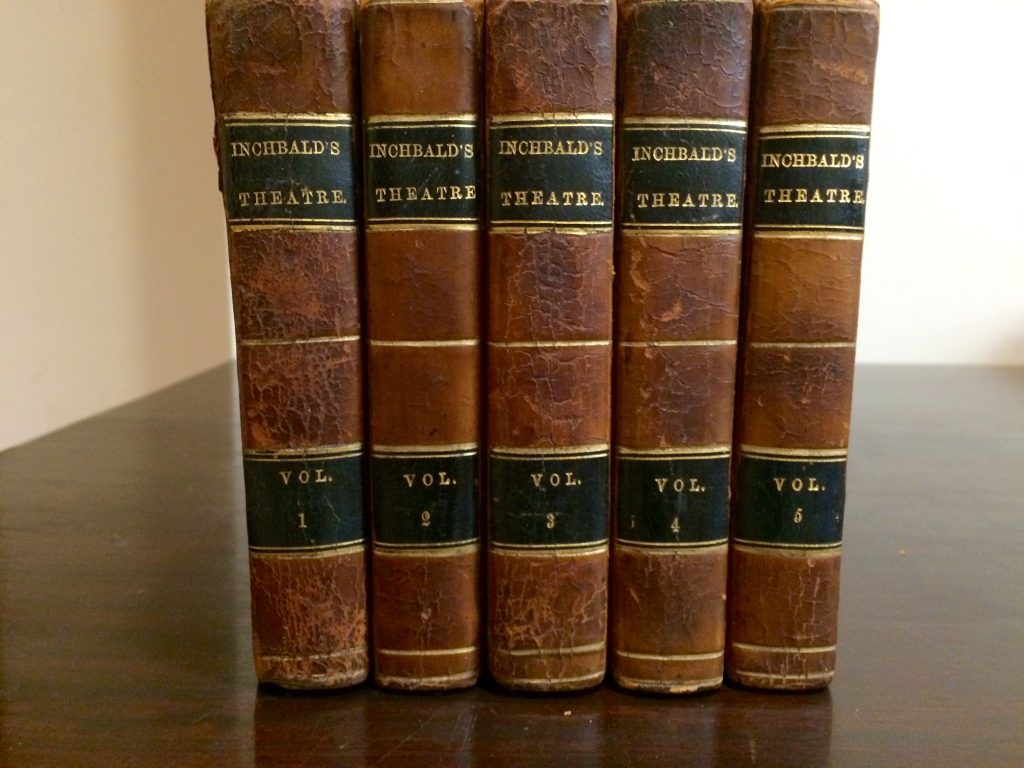

These beautiful bindings of the first edition of Inchbald’s British Theatre feature her name in equal prominence with the subject of the books. (PR 1243 .I4 1808, v.1-5 shown)

As the works of all three Elizabeths shown here intimate, Shakespeare’s education was closer to their own than it was to Voltaire’s or Johnson’s. His work and success, like theirs, trespassed social and moral boundaries. Shakespeare’s rise to “genius” glimmered with the possibility of their own fame.