This week’s post is written by Anne Causey, Public Service Assistant at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library:

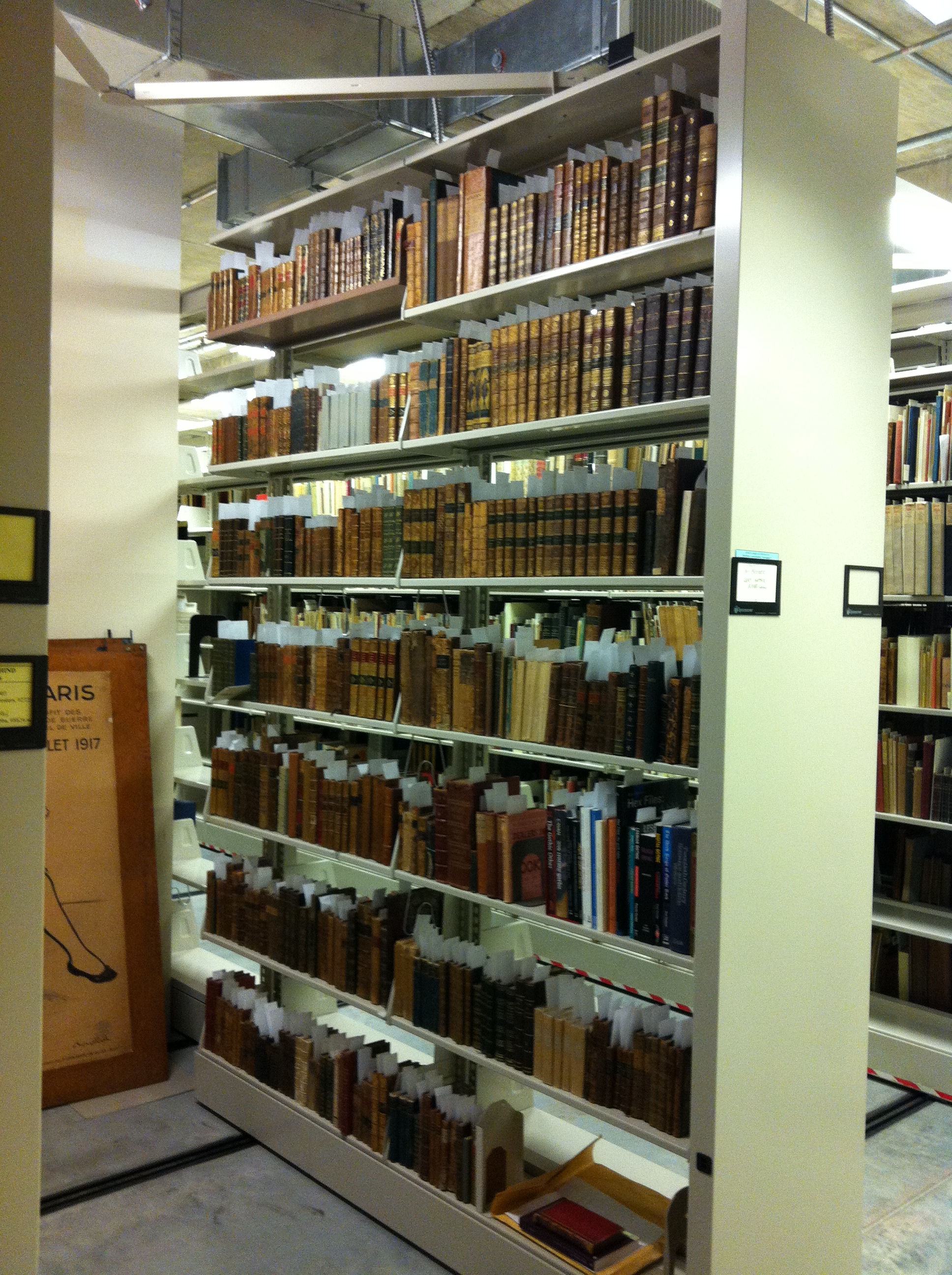

Local bookmakers and bookbinders involved with the Virginia Arts of the Book Center (VABC) in Charlottesville are gearing up for this year’s collaborative project: creating a miniature book. In fact, each participant must make fifteen books. What better way to become inspired than to visit the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, which houses more than 13,000 miniatures?

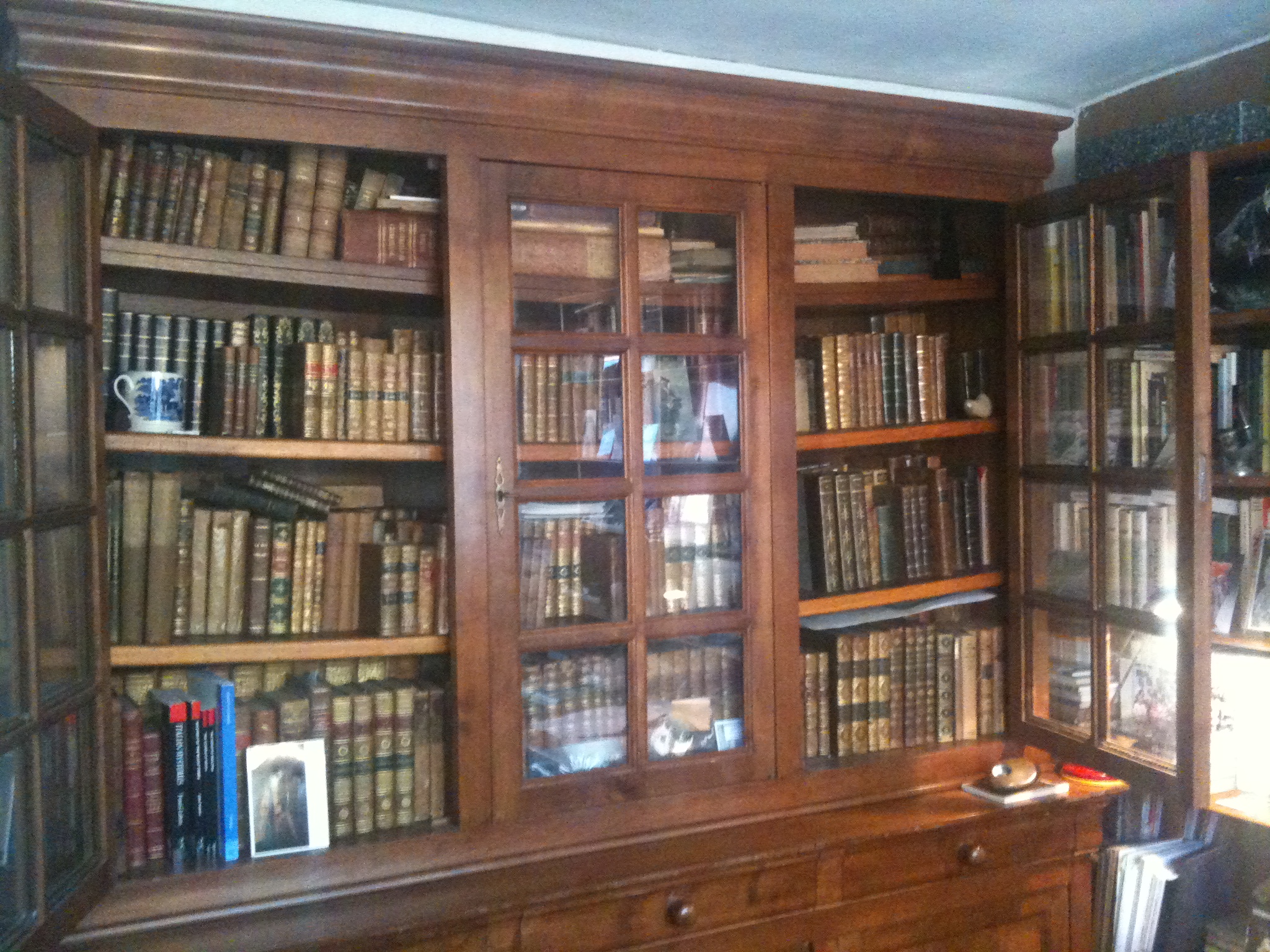

Here the 15 bookbinders and bookmakers investigate several boxes of miniature books, primarily from the McGehee Miniature Book Collection. I pulled some older more traditional printed books and then some contemporary artists books that use a variety of materials, binding and art work. They were excited by many of the examples – and excited by the housings as well. (Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

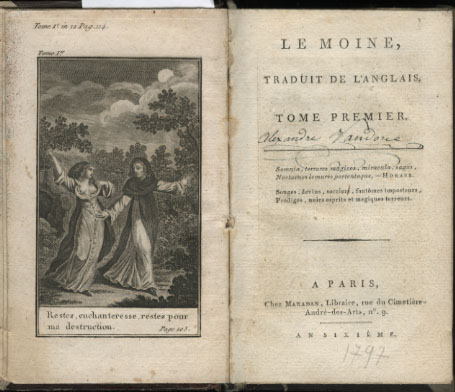

Miniature books are defined as smaller than three inches in each direction, and yes, they are “real” books – just printed on a smaller scale. The printer uses a text small enough to fit the size and form of the pages and sizes down the illustrations.

The participants looked at about 40 examples, including a Medieval Manuscript. A Parisian, miniature book of hours, dated from the 14th-century is the oldest such book in Special Collections. This tiny book contains five full-page illustrations and a vine design on every page, not to mention grotesques in the form of dragons and other beasts on some of the pages.

I am showing the group a 14th-century illuminated manuscript, a Parisian book of hours. Nicknamed “Baby,” it is 6.5 X 5 cm and 239 folios, or pages. The text is Gothic script on vellum and is in Latin except for the 12-page calendar, which is French. We had it rebound in a historically-correct leather binding with ties. The group was almost as interested in the 19th century red velvet binding that was removed but still kept with the book. (MSS. 382 /M.MS. W. From the Papers of Edward L. Stone, purchased 1938. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Books in miniature were made for various reasons. Some were made small so they were easy to carry, while some accompanied packages as advertisements. Some were made for children, and still others were made because the content of the book or its ownership was controversial.

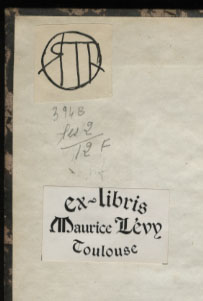

The miniature books in Special Collections comprise a wide range—from traditional older printed books to more whimsical artist books. The collection includes more than 12,000 miniatures donated by Mrs. Caroline Brandt. Her collection has accumulated over 40 years, spans six centuries and contains volumes in more than 30 languages. Mrs. Brandt donates more books to the collection every year.

The VABC is hosting an exhibition, entitled Monumental Ideas in Miniature Books 2: A Traveling Exhibit from March 1 – April 26 at the Virginia Arts of the Book Center, 2125 Ivy Road, Charlottesville, VA.

VABC will host a reception during the Virginia Festival of the Book on Sunday, March 24 at 2:30PM, including a discussion of the exhibit by Molly Schwartzburg, curator of the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. During March, Special Collections will also have an exhibit from its holdings of miniature books to coordinate with this visit.

This group of miniatures were all designed and hand-written by contemporary bookmaker Margaret Challenger between 1999 and 2003. Several are accordion-style, and all of them have specialty hand-made papers and Challenger’s calligraphy. The book with the black cover and gold center medallion, which shows a knight’s shield and sword, is called “St. Patrick’s Breastplate.” Enclosed in the front cover is another smaller book, containing his prayer; her calligraphy, written in purple is, “an Anglo Saxon version of Italian Uncial, as used in The St. Cuthbert Gospels, written before 716 A.D.” Many of the books have interesting paper closures or boxes. I was hoping such variety would give the bookmakers inspiration for their own projects. (Lindemann 3747-3760. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

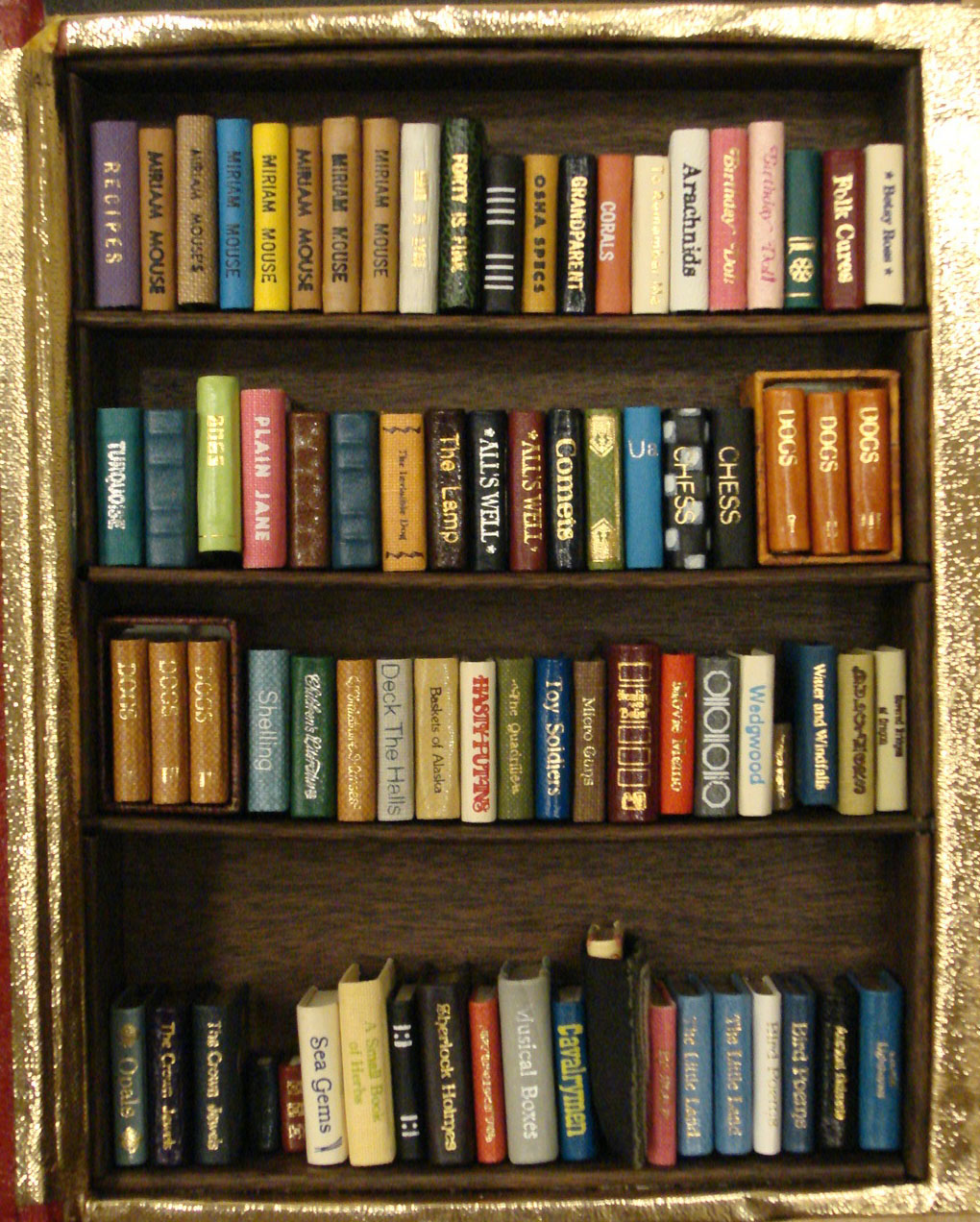

This red and gold miniature bookcase, which is the size of a more typical book (6 1/4 x 7 ½ in), holds 65 tiny volumes. They are each bound in colorful book cloth and have tiny text. The first one, “Aunt Faith’s Recipes,” does indeed contain actual recipes – for desserts, candy, and beverages. I only know this because the group wanted a book to be taken out to see if it contained text. Less than half of these are known as micro-minis, which are between 1” to 2” tall, while the rest are ultra-micro-minis, defined as smaller than 1” in any measurement (Lindemann 5766, no. 1-65. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

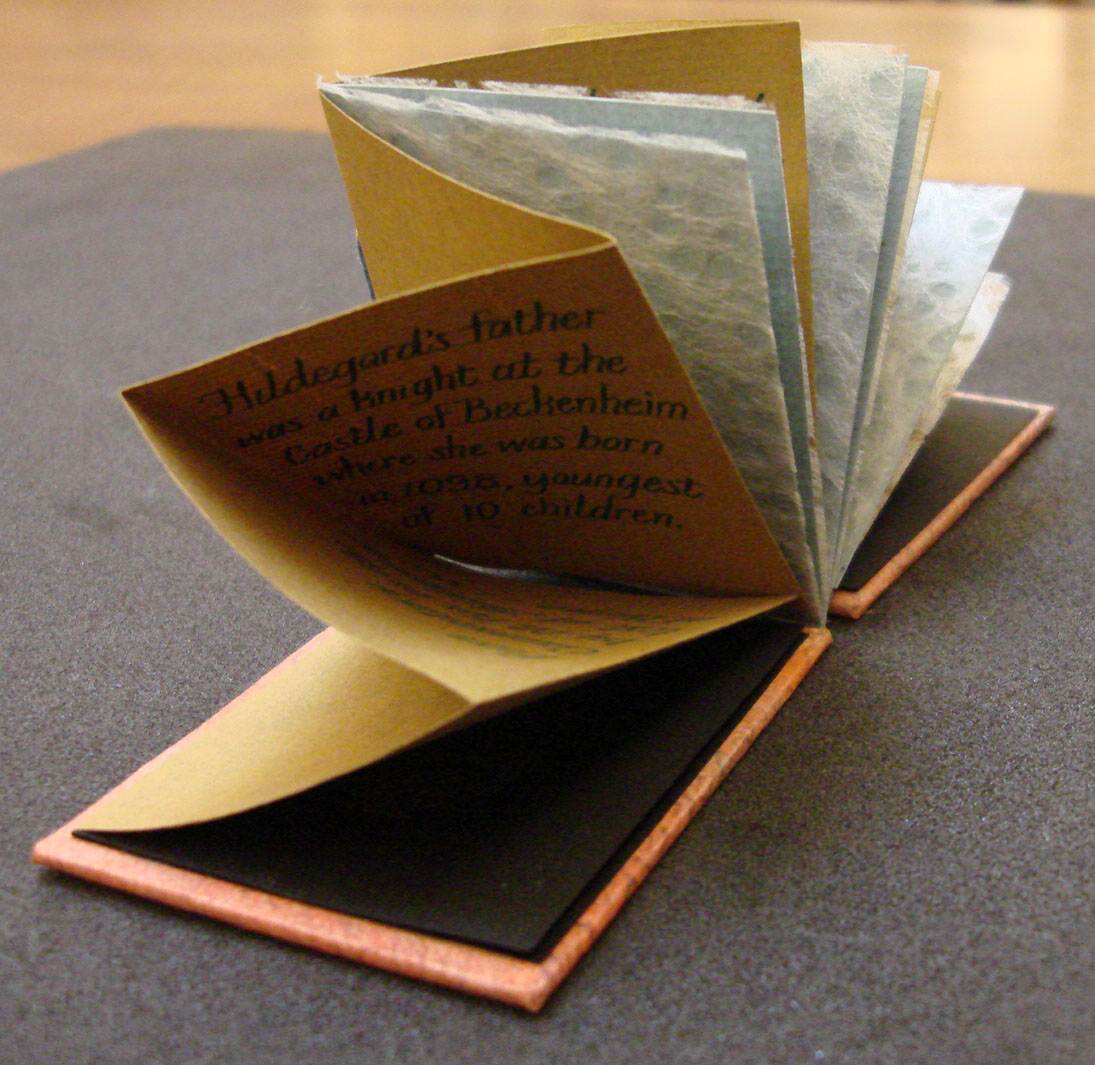

This accordion-style book has a bright orange cover and is enclosed in a black envelope stamped with a silver cross. It is entitled “Hildegard of Bingen: Her Music.” The calligraphy in green is “from Commentary by M. Fox on the text of Hildegard of Bingen: 1985.” Hildegard was a saint born in 1098 who composed over 70 songs. The book is a creation of Margaret Challenger, 2000. The colophon reports that she used Ingres paper and gouache calligraphy. (Lindemann 03747. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

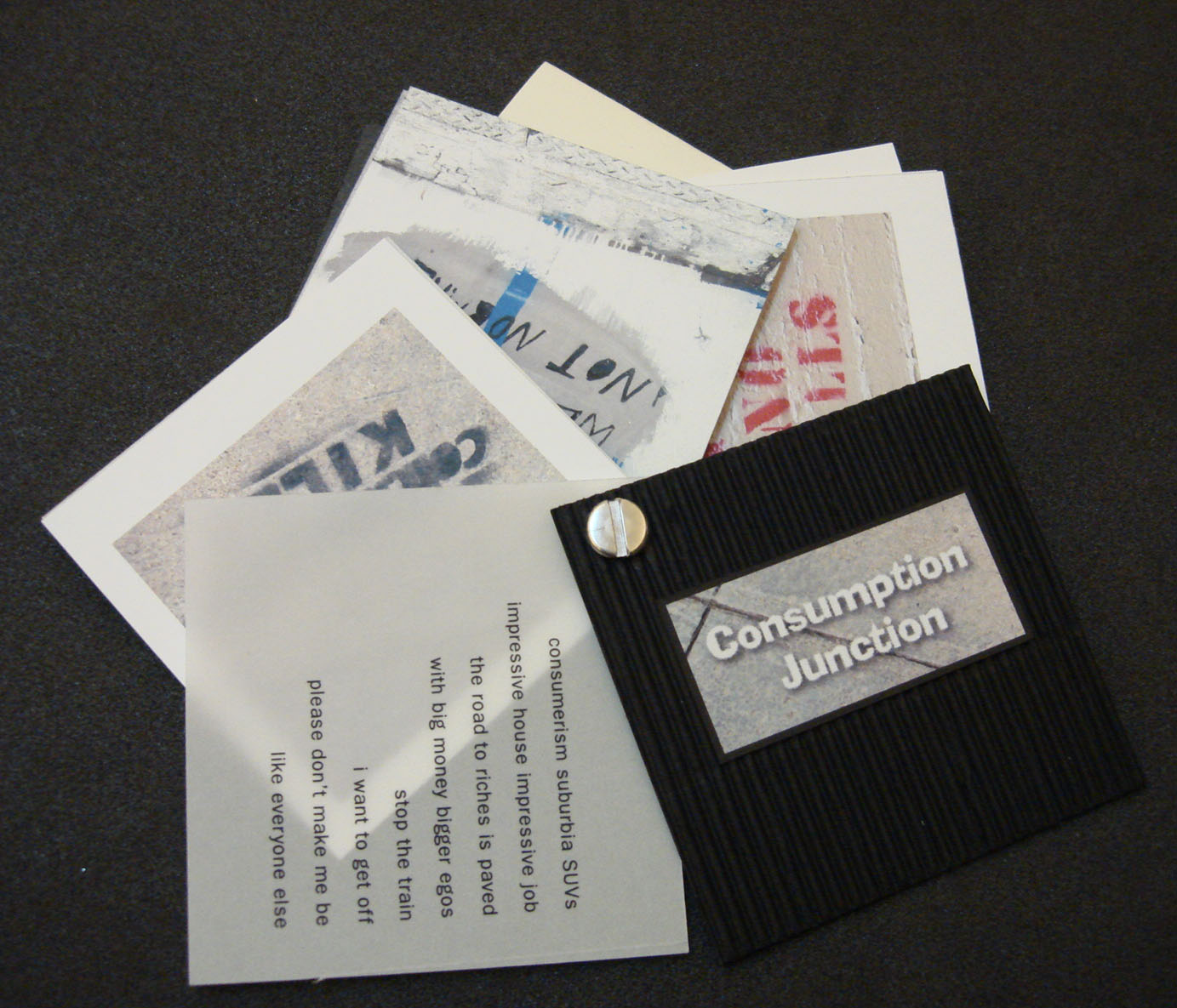

Miniatures are sometimes commentaries about the times in which we live. For instance, “Consumption Junction” a miniature created by Laura Russell in 2002, features painted corrugated cardboard covers, affixed by a single bolt. The book is a protest against modern consumerism. (Lindemann 05115. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

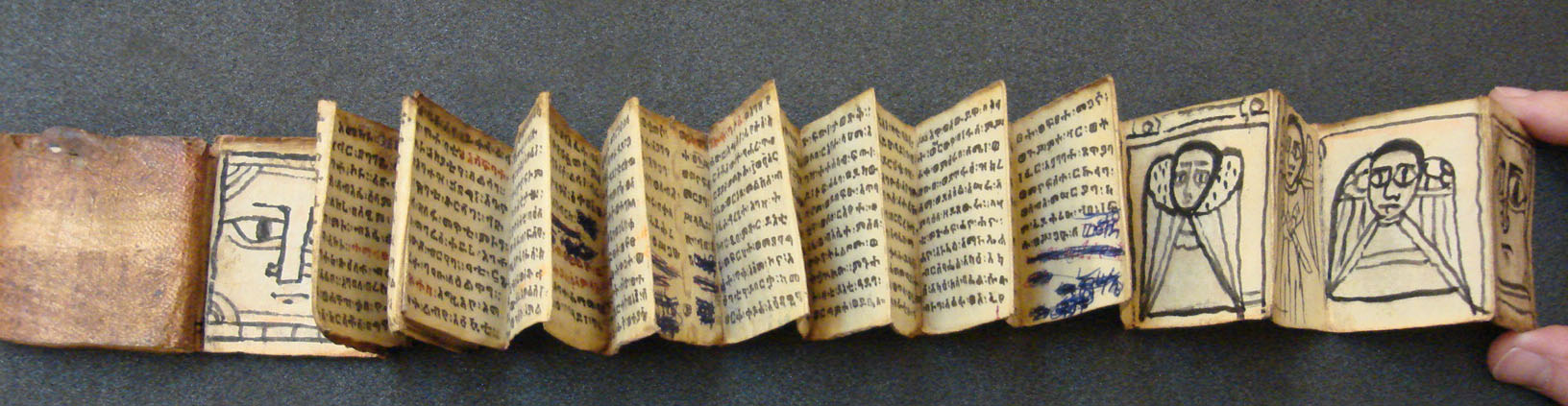

This manuscript from Ethiopia looks rather old, but is estimated to date from the twentieth century. The script is in black and red ink on vellum, and the vellum binding wraps around the accordion-style text block. There are 7 hand-painted illustrations. (Not yet cataloged, from the McGehee Miniature Book Collection. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

The “I, Robot” miniature is too cute! The group chuckled at this one. The robot “covers” or container is metal with a magnetized closing at the back of its head. The fun surprise comes in opening it and pulling out the pages. This creative miniature was made by Jan and Jarmila Sobota, in the Czech Republic, 2007. Ours is number 3 of 30. (Not yet cataloged, from the McGehee Miniature Book Collection. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)