We are proud to announce the acquisition of a major collection of the papers of Lewis M. Dabney, III, the late scholar of American literature and Professor of English at the University of Wyoming. Dr. Dabney is best known for his magisterial 2005 biography, Edmund Wilson: A Life in Literature, and a large body of scholarship on Edmund Wilson.

Lewis M. Dabney, III, undated, courtesy of Elizabeth Dabney Hochman

The UVA Library is now home to three groups of Dabney’s papers: his voluminous and meticulously prepared Wilson archives; a small set of materials documenting his book on William Faulkner, The Indians of Yoknapatawpha (1974); and a collection of papers of Dabney’s mother, Crystal Ray Ross Dabney, documenting her romantic relationship with John Dos Passos in the 1920s.

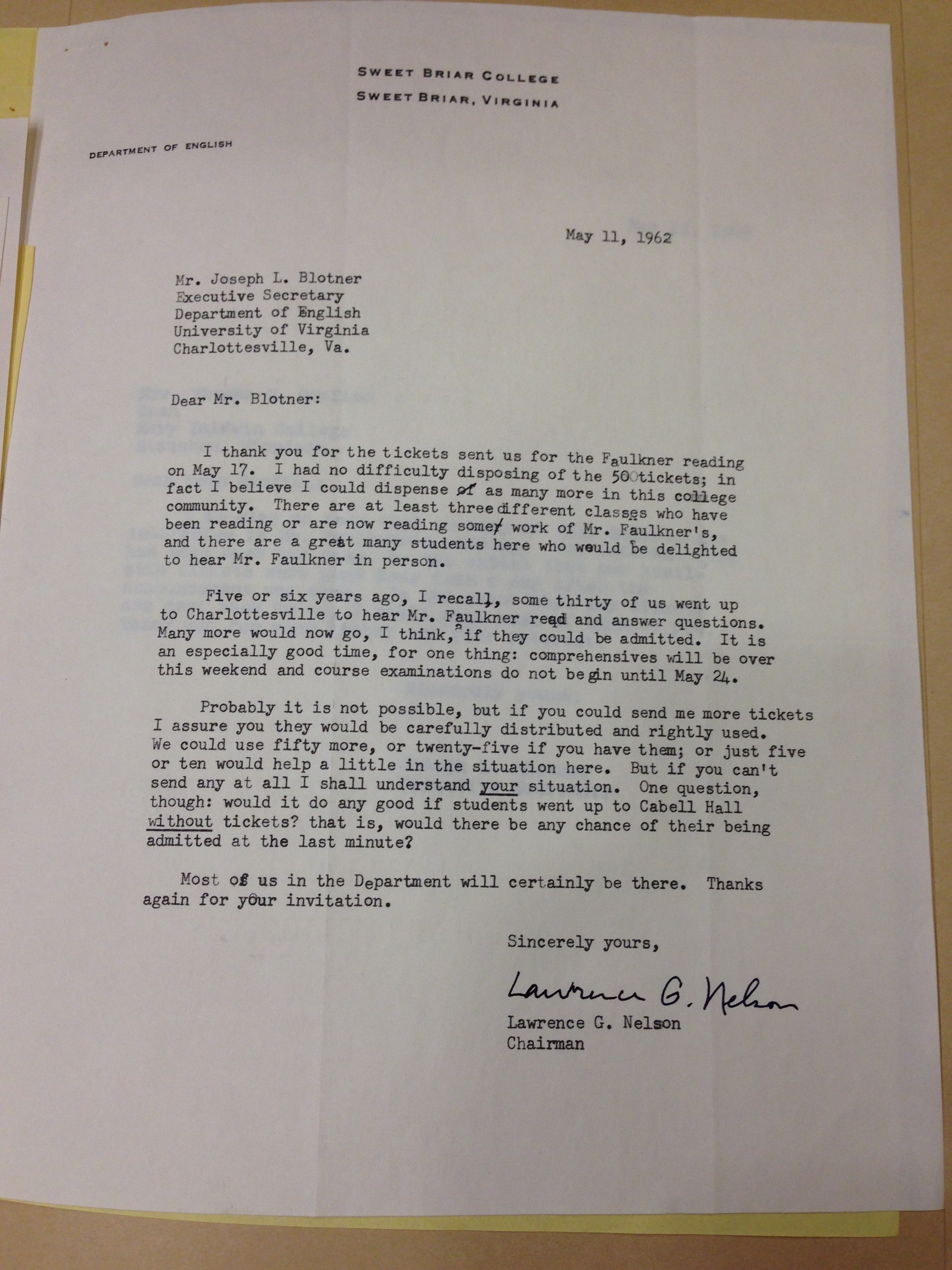

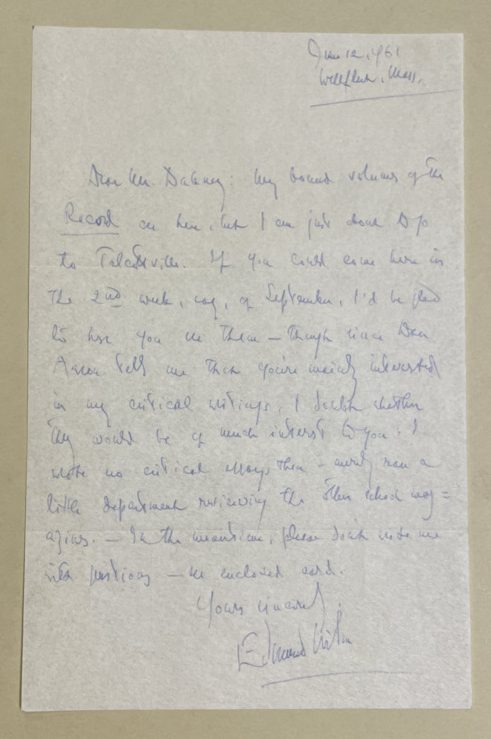

The earliest letter from Edmund Wilson to Lewis Dabney in the collection (Box 12.7). The correspondence begins with answers to Dabney’s questions about a school periodical from Wilson’s youth, and moves on to many other topics.

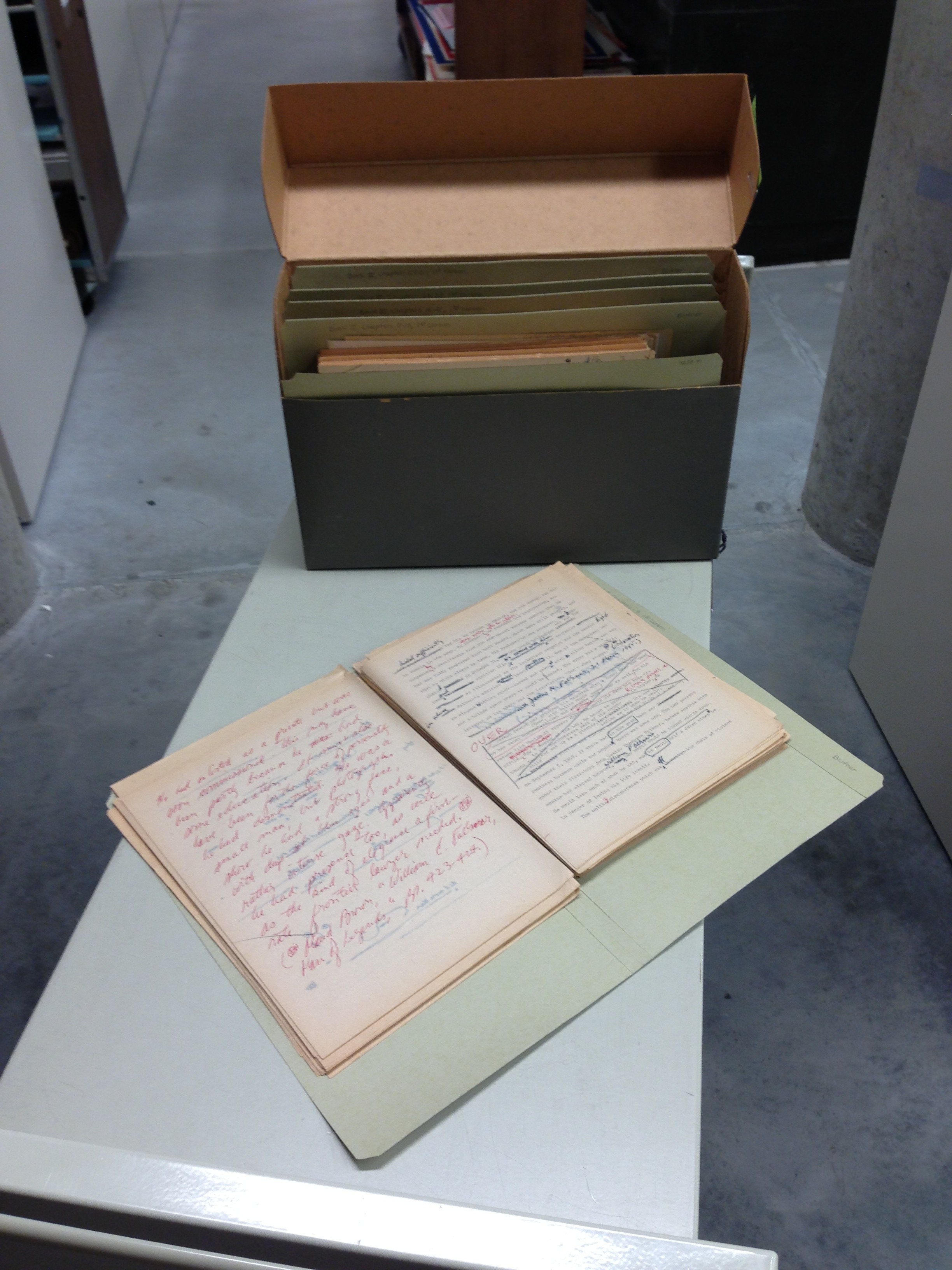

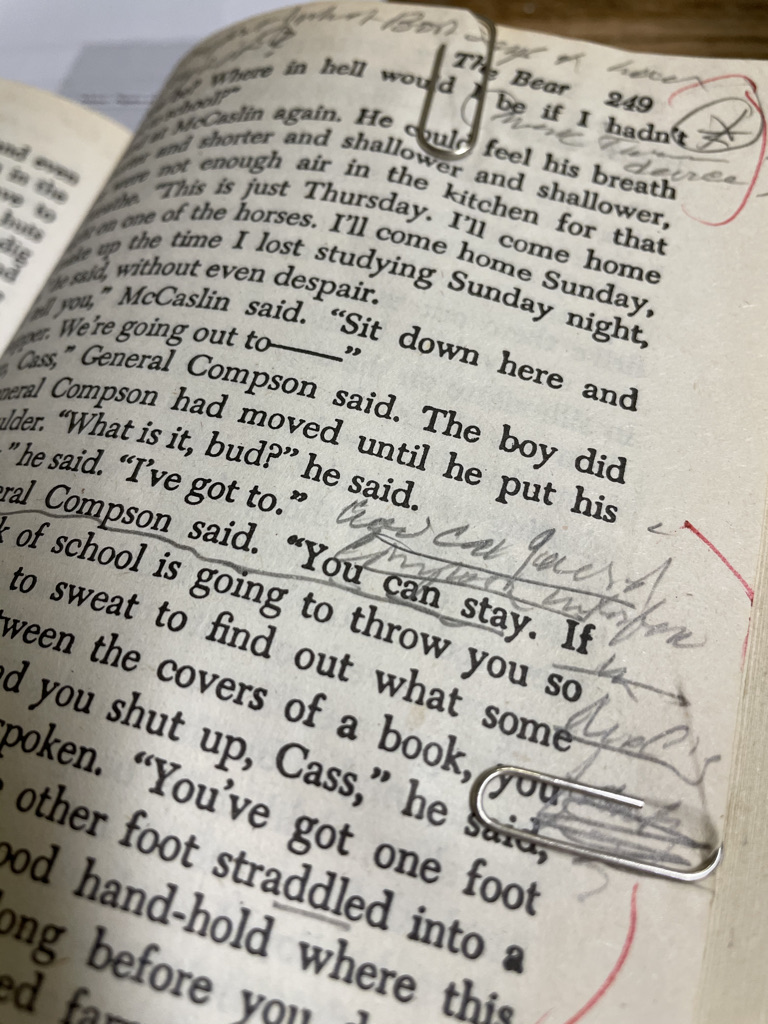

Dabney’s heavily annotated copy of William Faukner’s “The Bear” (Box 19), used in his research for “The Indians of Yoknapatawpha.”

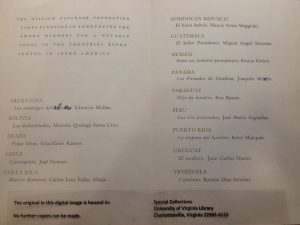

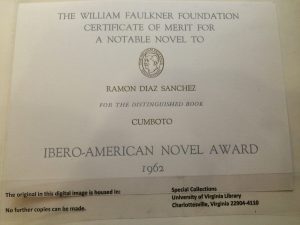

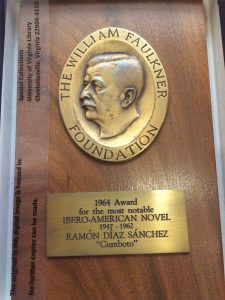

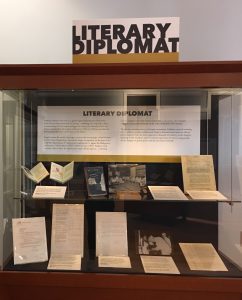

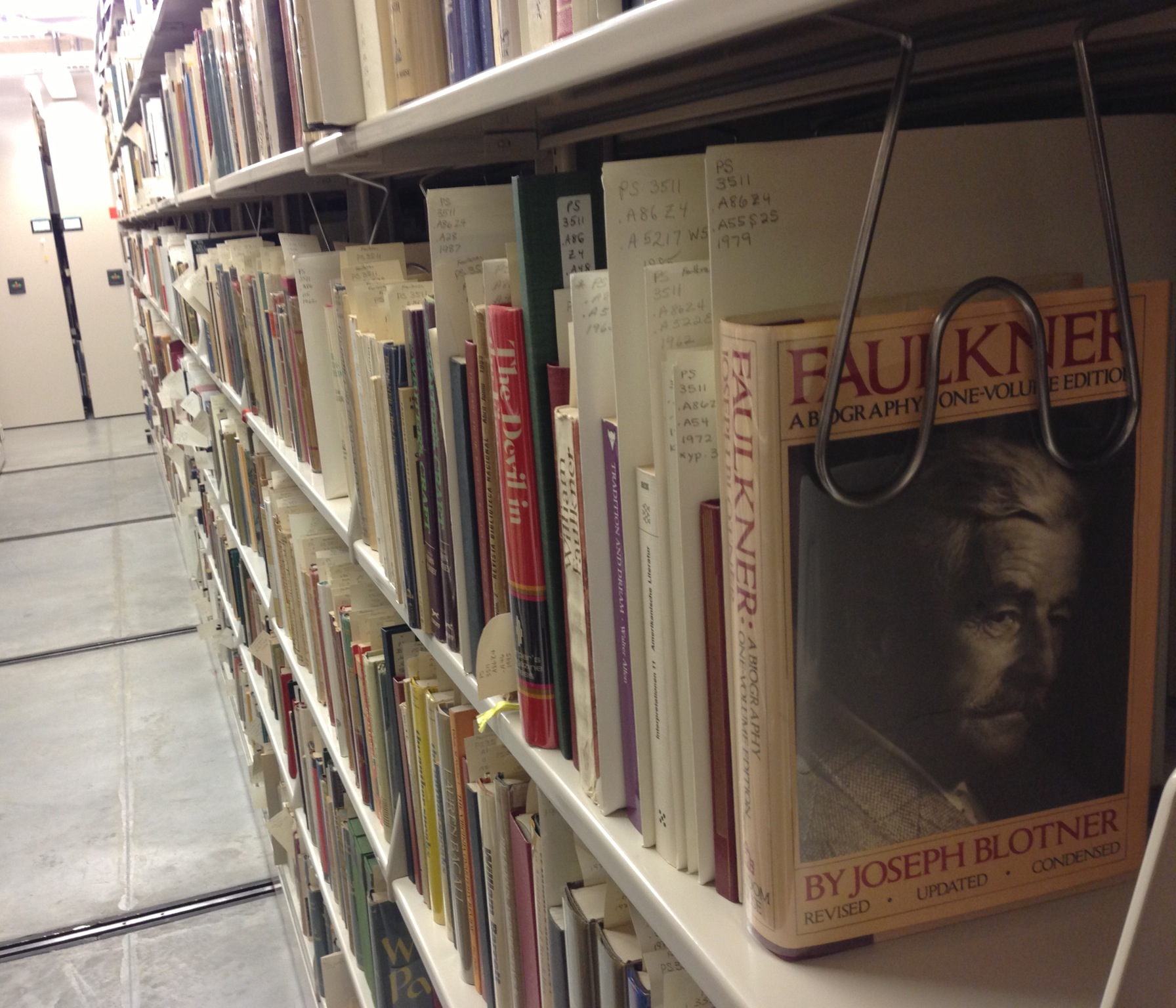

Each of these groups of materials individually has significant connections to existing collection strengths at the library: the Faulkner materials join our more than eighty archival collections related to Faulkner, and the Crystal Ross-John Dos Passos collection is an essential complement to the Papers of John Dos Passos. Edmund Wilson’s profound reach across American literary modernism means that Dabney’s research files for this project will have important links throughout the archival collections in the Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature. We are grateful to Dabney’s family for choosing the University of Virginia as a home for these materials: his widow Sarah Dabney, daughter Elizabeth Dabney Hochman, and son Lewis M. Dabney IV (CLAS 1992).

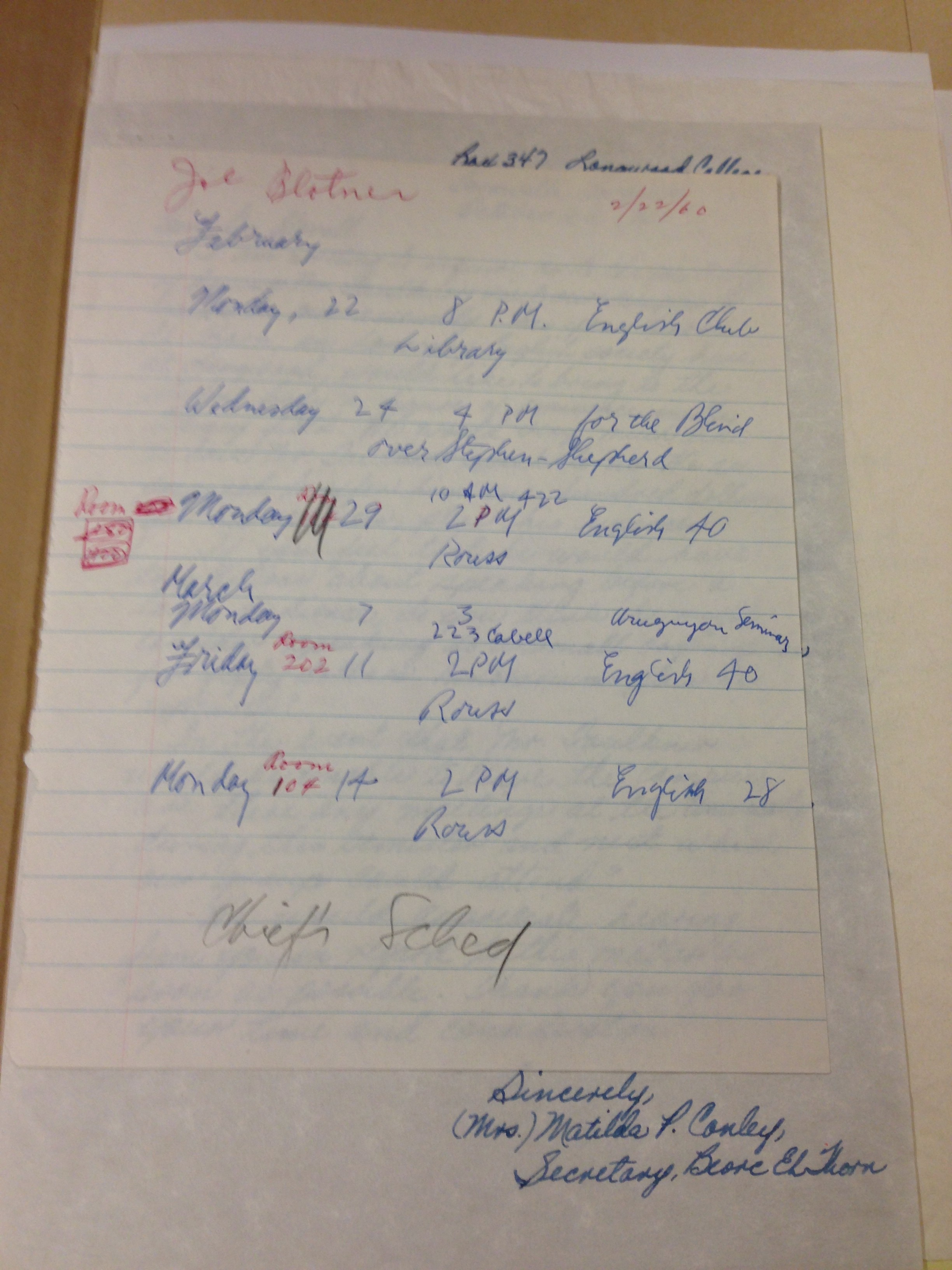

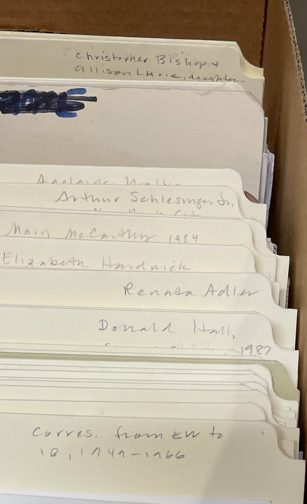

An example of the tantalizing folder headings in just one box of the collection. Dabney worked with a professional archivist to organize his papers in the years leading up to his death in 2015.

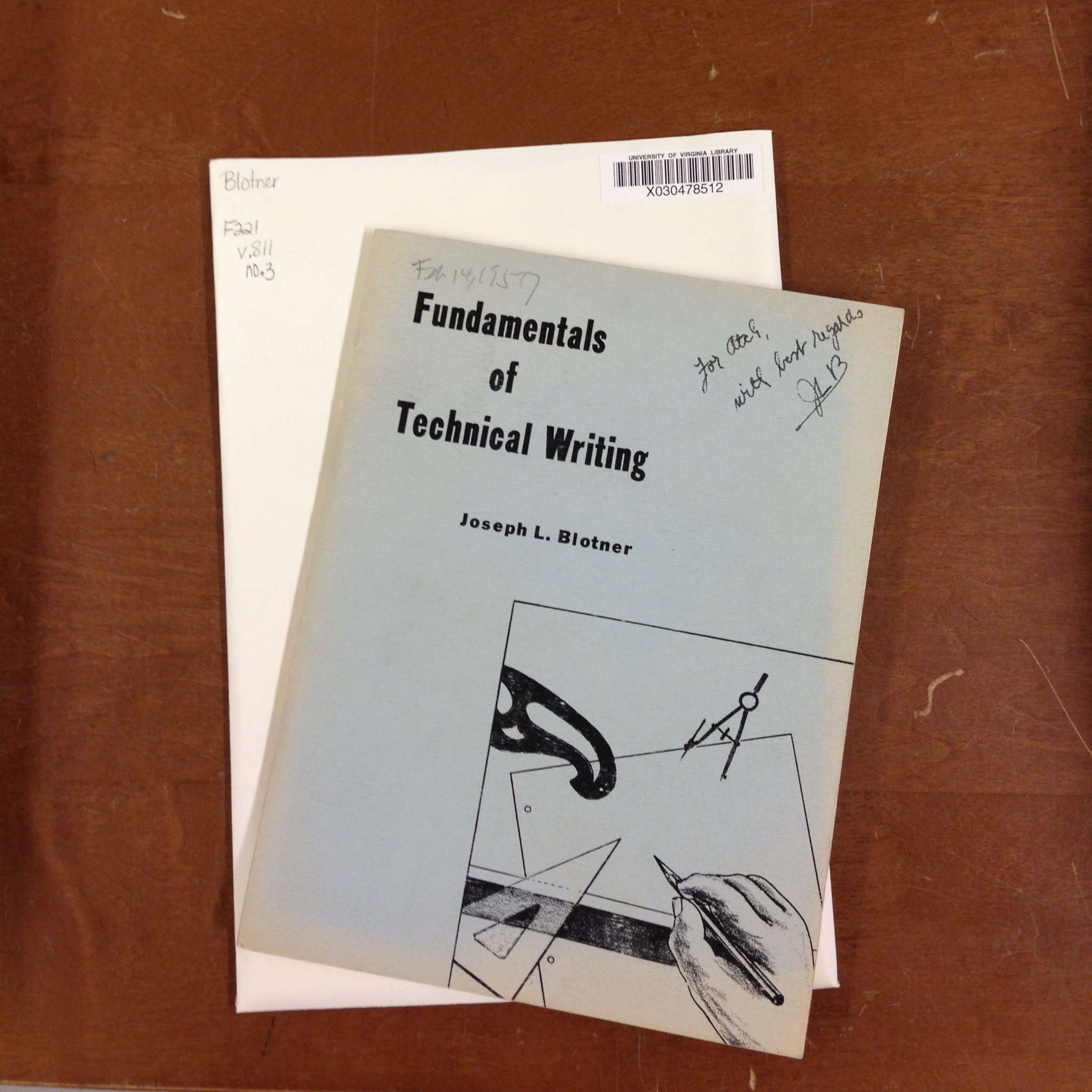

Dabney’s scholarship on Edmund Wilson began while he was still a graduate student and came to know Wilson personally. It includes not just the biography but major editions of Wilson’s work, including The Portable Edmund Wilson; The Edmund Wilson Reader; The Sixties: The Last Journal, 1960-1972; and Edmund Wilson: Centennial Reflections. He also edited two Library of America volumes, Edmund Wilson: Literary Essays and Reviews of the 1920s and 30s, and Edmund Wilson: Literary Essays and Reviews of the 1930s and 40s.

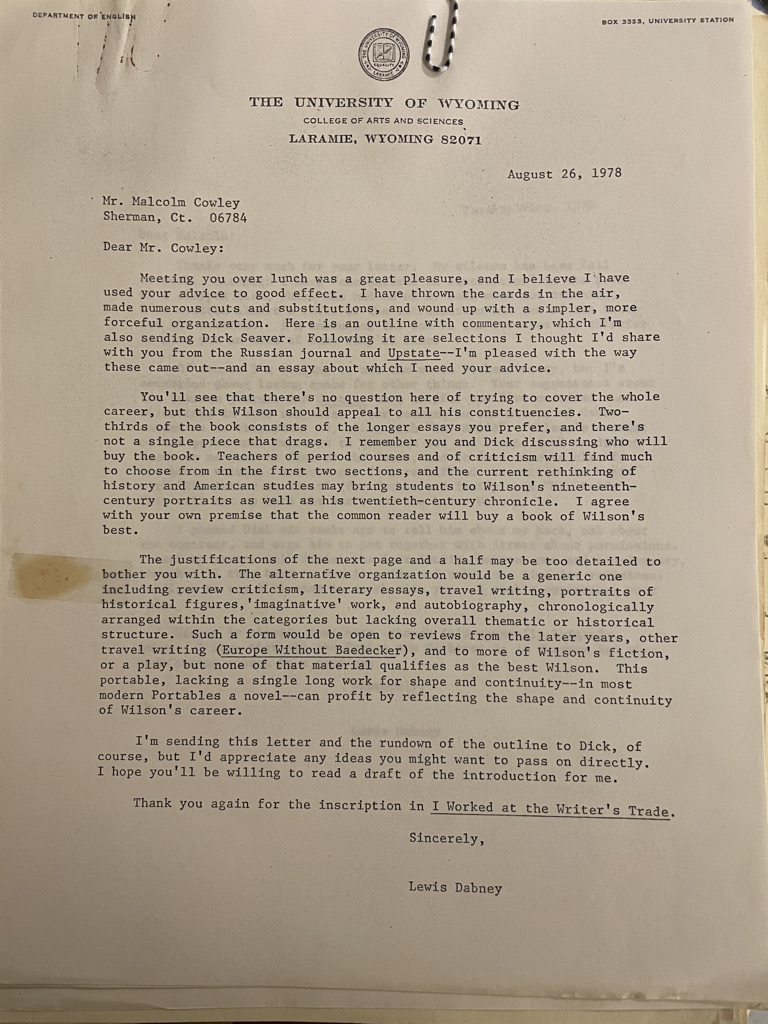

File copy of a letter from Dabney to Malcolm Cowley, from an extended correspondence on the structure and contents of Dabney (ed.), “The Portable Edmund Wilson,” 1978 (Box 3.48).

Wilson looms large in the history of twentieth-century literature and culture, and it is no surprise that Dabney’s biography was the work of a lifetime. The biography will never be surpassed due to the access Dabney achieved to the living record of Wilson’s life: his files hold his communications with Wilson himself and Wilson’s friends and colleagues, including figures such as Malcolm Cowley, Donald Hall, and Lionel Trilling; also present are transcripts from his interviews with eminent literary figures such as Wilson’s one-time wife Mary McCarthy, Elizabeth Hardwick, Svetlana Alliuyeva, Isaiah Berlin, Elena Wilson, Roger Straus, and others; in some cases, cassette tapes of the original interviews are present. Much of this material remains unpublished. Dabney’s notes from the interviews offer a taste of Wilson’s dramatic romantic and literary relationships, and like the rest of the collection, offer valuable insight into the biographer’s process.

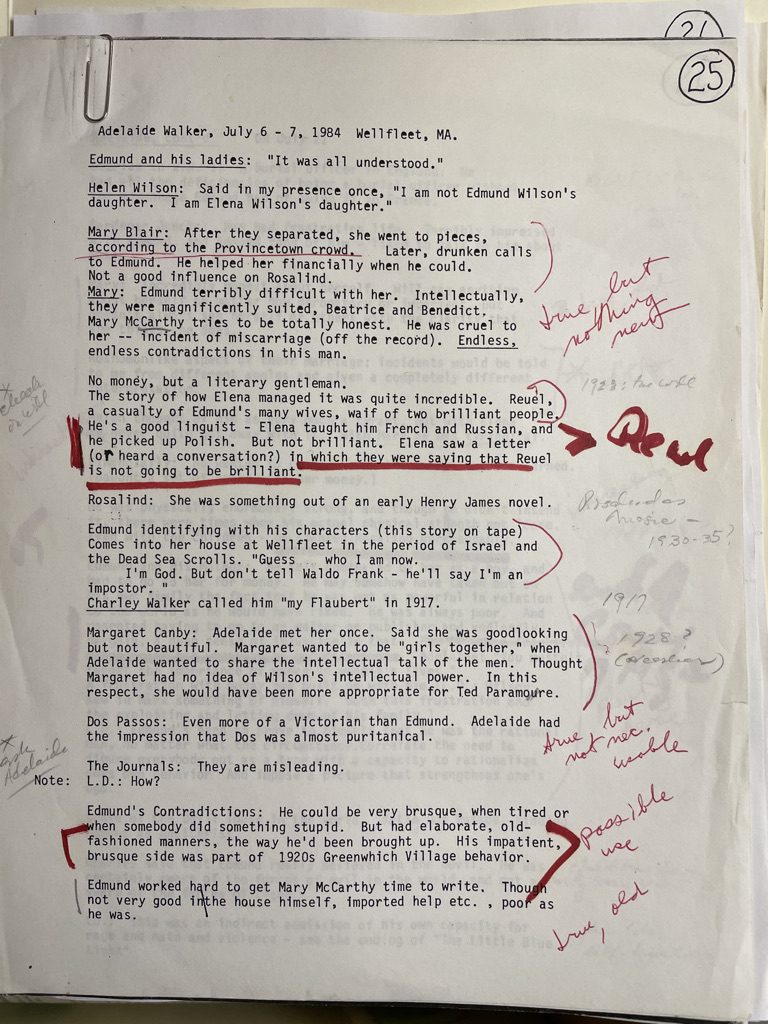

Dabney’s notes from his multi-day interview with Wilson’s friend Adelaide Walker in 1984, heavily annotated (Box 7.29)

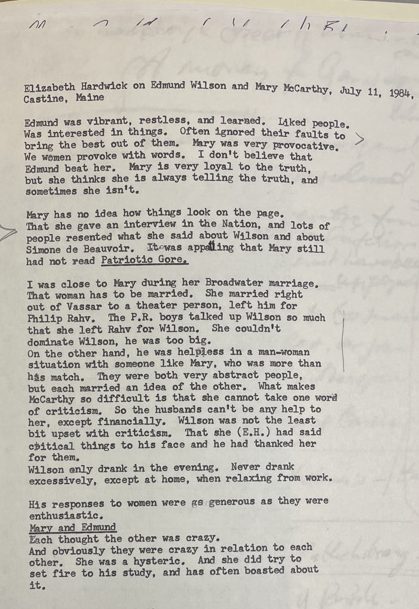

Dabney’s notes from interview with Elizabeth Hardwick regarding Wilson and Mary McCarthy’s relationship, 1984 (7.21)

Among the materials in the collection is Dabney’s prized typescript copy of Edmund Wilson’s journals. This copy was one of two made at the request of Wilson’s longtime publisher Roger Straus since Wilson’s handwriting was apparently nearly indecipherable. Straus gave one copy to Dabney, and the other resides with Wilson’s papers at the Beinecke Library at Yale.

The William Faulkner and Edmund Wilson portions of the collection will be made available to researchers as soon as they have been processed.

Crystal Ross and John Dos Passos

At the time of his death, Dr. Dabney had recently completed a draft of a book on the relationship between his mother and John Dos Passos. The two were briefly engaged in the 1920s, and remained friends their entire lives. Dabney’s family are publishing the book, and once it is released this portion of the collection will become available to scholars. When that happens, we will post again to this space.

If you have questions about any portion of the Dabney papers, please contact curator Molly Schwartzburg at schwartzburg@virginia.edu