This week, we are pleased to feature a second guest post by Ethan King, one-time Special Collections graduate student assistant, who is now pursuing his Ph.D. in English at Boston University. Ethan takes a strong interest in Faulkner, and has generously written for us about Faulkner’s fascinating later-life work as a cultural ambassador, a subject featured in our current exhibition, Faulkner: Life and Works.

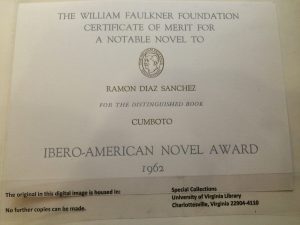

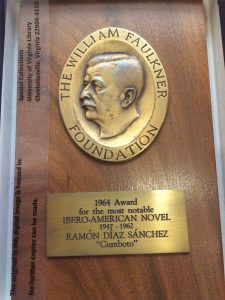

In my previous post, I examined the divergent geopolitical visions of William Faulkner and the U.S. State Department as manifested in their practices and attitudes before, during, and after Faulkner’s trip as a cultural ambassador to Venezuela in the spring of 1961. Impressed by those he met in Venezuela, and his sympathy elicited by stories about the difficulties for Latin Americans of publishing fiction in and outside of Latin America, Faulkner proposed the Ibero-American Novel Project, a competition administered by the Faulkner Foundation through which Latin American books could seek translation into English and publication in the United States. The plan was to identify the best novel written in each Latin American country since the end of World War II and not yet translated in English and reward those winners with a Certificate of Merit from the William Faulkner Foundation, with the overall winner receiving a plaque. The Foundation’s statement regarding the project is as follows:

Many novels of the highest literary quality written by Latin-American authors in their native languages are failing to reach appreciative readers in English-speaking North America; and accordingly the William Faulkner Foundation, at the suggestion of William Faulkner himself, is undertaking a modest corrective program in the hope of contributing to a better cultural exchange between the two Americas, with an attendant improvement in human relations and understanding (MSS 10677).

However, as Faulkner died soon into the Project’s infancy, the Project ran into a host of challenges and difficulties created by the market forces of the United States. Without the ability to offer a cash prize to the winners from each of the represented regions of Latin America, Project officials had hoped Faulkner’s prestige would be enough for publishers to take on Latin American novels to be translated and published in the US, but unfortunately, publishers often refused, citing lack of commercial interest.

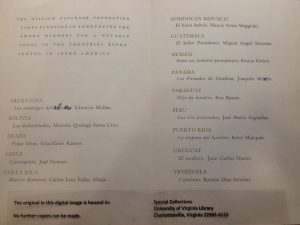

Before his death, Faulkner chose Arnold del Greco, an associate professor of Romance Languages at the University of Virginia, to direct the Project. In del Greco’s own words in a 1974 letter to Martha Murray, a teaching assistant at Southern Methodist University, his role as Project director “entailed all aspects of [the] project: preparing program and announcements, appointing judges in each country (usually after receiving wide recommendations from critics, etc.), reviewing decisions through the home board, seeking publishes for the American editions, etc” (MSS 10677). Under del Greco’s tutelage, the Project sought to compose panels of three judges from each country, none of whom, the Foundation’s statement reveals, was “to be older than twenty-five years of age on the grounds that youngsters are best able to evaluate the work of their contemporaries.” Each panel of judges was to read all submitted novels from their nation and identify the best “on the basis of literary distinction and achievement” (MSS 10677). Although this part of the competition was supposed to be completed by the end of 1961, it was not until February of 1963—half a year after Faulkner’s death—that the prizewinners were announced.

After broadcasting these winners throughout the US and Latin America on the “Voice of America,” the Project moved into the next phase—the selection of the best overall novel. Based at the University of Virginia and composed of six doctoral students and two assistant professors, as well as del Greco himself, the final panel of judges selected Díaz Sánchez’s Cumboto to be the most outstanding novel. Despite its meritorious achievement, Cumboto followed an agonizing trajectory in its quest for translation and publication. In her essay on Faulkner’s Ibero-American project that appeared in The Southern Quarterly (Winter 2004), Deborah Cohn characterizes Cumboto as being a novel about “a rural black community and the problems of race relations and mestizaje in Venezuela” (12). Shortly after receiving the Project’s highest honor, the novel was initially considered for publication by the University of Virginia Press and Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. However, both rejected it outright. Over the next few years, del Greco offered the manuscript to over twenty different publishing companies, all of whom denied publication for the novel based on their readers’ active dislike of the novel as well as on the difficulties of finding a market for it in the U.S. For example, Frank Wardlaw, Director of the University of Texas Press, rejected del Greco’s request for them to consider the novel because the “principal advisors on our Latin American translation program […] are emphatic in their recommendation that we do not publish it. Quite frankly, they do not have a very high opinion of the novel” (MSS 10677). Another example from Eric Swenson, Vice President and Executive Editor at W.W. Norton & Company Inc.: “I am afraid [Cumboto] would elicit very little response from a broadly-based North American audience, which I suppose is another way of saying it does not seem to us to be important enough to be worth the time and effort of translation and publication” (MSS 10677). Though none of the editors indicated precisely why the novel would not be of interest to readers in the U.S., Cohn surmises that it had to do with the novel’s intense regionalism: that because of its “emphasis on local color, […] it was even less likely to be of interest to a US audience” (13). Or in other words, while Faulkner’s regional focus on the US South was critically lauded, regionalism employed by writers from Latin American countries struggled to reach a US audience.

In a letter written to José Antonio Cordido-Freytes—a member of the Faulkner Foundation—Díaz Sánchez scathingly and articulately expressed his frustrations with the competition’s outcome, pointing out the very hierarchic geopolitical climate that the Project sought to break down:

The resistance of North American publishers to publish Latin American literary works is well known to me, which is more than sufficiently explained by the contempt with which the people of North America look down on our Southern countries, on their institutions, their history and their language. I had thought that the prize for a novel granted by the William Faulkner Foundation was actually aiming to help break down this barrier of contempt and inexorable utilitariarism [sic] which the North Americans have created between the two racial zones of the New World and to lend a bit of ethical and aesthetical dignity to the relationship between the greatest power of modern history and our small and under-developed nations. […] The only satisfaction and the only positive value that such a tournament could give us, the writers of Latin America, would be the publication in the U.S. of the books produced in our countries and which carry a message of good faith, because besides this there is nothing very attractive about the giving away of a metal disk not any more important or honoring than those distributed for propaganda purposes for international industrial products. By this I don’t intend to say that I consider the Faulkner Prize to be a mere artifice invented for advertising of one of these products, but the truth is that up to this moment, it looks quite a bit like it. […] Considering these circumstances, please tell me frankly: What is the efficacy of the Faulkner prize? (MSS 10677)

Charged by this letter to up the ante in seeking Cumboto’s publication in the US, the Foundation finally authorized a $2,000 allotment to bankroll its English publication, but this money didn’t help until two years later, when Wardlaw inexplicably agreed to review the novel again. Likely incentivized only by this money, Wardlaw commissioned its translation and publication in 1968. Heartbreakingly, however, Díaz Sánchez died a few months before its publication, never seeing his translated work circulating in the United States, nor his nomination for the National Book Award that year.

While the Ibero-American Project set out to “contribut[e] to a better cultural exchange between the two Americas,” it is hard to see anything but its unfulfilled potential from the sad tales of its outcome. Although Coronación and El señor presidente, as well as novels not entered into the competition by Mallea and Marqués, were published in English, Cohn points out that “no work by any of the other prizewinning authors has ever been published in English” (11). One wonders, then, as Díaz Sánchez did, “What is the efficacy of the Faulkner prize?” Perhaps if Faulkner himself had lived past the Project’s infancy, he could have wielded his tremendous literary weight among US publishing to better effect in achieving its goals.