This post is contributed by Derrais Carter (he/they), a writer, book artist, and Assistant Professor of Gender & Women’s Studies at the University of Arizona. As a William A. Elwood Fellowship recipient, Carter used his research to investigate links between Julian Bond and blaxploitation cinema.

I went in search of conspiracy. For a length of time, that I’m slightly embarrassed to admit, I have searched for information about a group of well-intentioned activists who live in my mind as a cabal. Their mission was to rid Black America of demeaning, stereotypical representations in film. They called themselves the Coalition Against Blaxploitation (CAB).

The CAB is said to have originated in 1972. Organized by Junius Griffin, the same man who coined the term blaxploitation, the CAB included activists from the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).[1] Blaxploitation, Griffin’s portmanteau of “Black” and “exploitation” names Hollywood’s attempt to capitalize on the film industry’s newfound interest in targeting Black filmgoing audiences. This interest resulted from the success of early 70s films including but not limited to Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971), Shaft (1971) and Superfly (1972). While these films were monumental commercial successes, they also raised questions around the quality of Black representation in film. Enter blaxploitation. Griffin used the term critically to expose Hollywood’s investment in stereotypical representations that were psychologically damaging to Black Americans. When he introduced the term in Variety, Griffin was the head of the Hollywood NAACP. In this way, he was well-poised to work with other civil rights organizations to merge their resources toward the greater end of the film industry’s anti-Black practices.

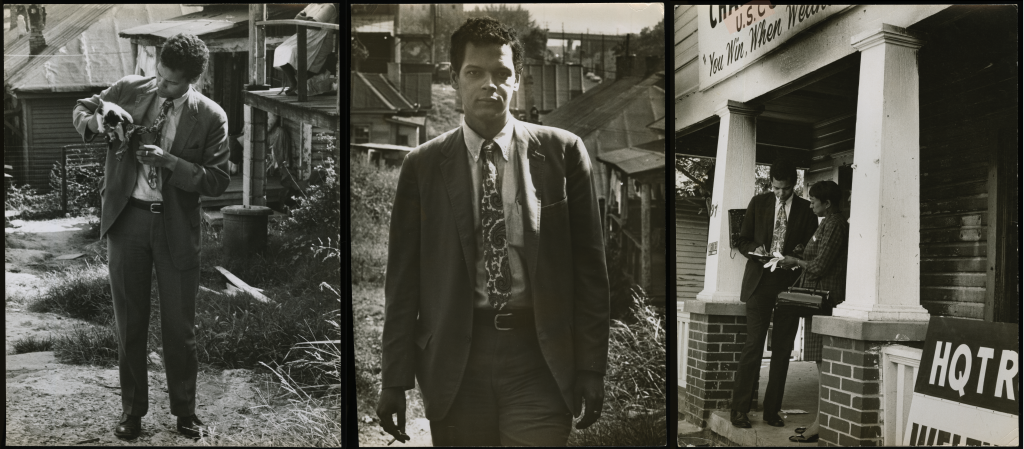

What has long intrigued me is the shadowy and nebulous way the group seems to have operated. Given the histories and racial triumphs of the organizations involved, I wondered why the CAB isn’t more visible in archival collections or trade publications. So, casting a wide net, I ventured into the Julian Bond Papers (MSS 13347 + accreations) at the Small Special Collections Library in hopes of finding incontrovertible evidence of the group’s existence. I don’t know if he was involved with them. But as a founding member of SNCC, I thought his papers might contain some information about the CAB and how they saw themselves extending SNCC’s political efforts. In the absence of a glaring piece of historical evidence, I would have settled for a letter, note, or photograph that provided insight into how the CAB operated.

I found nothing of the sort.

Slightly deterred, my curiosity never wavered. For the next few days, I abandoned my initial inquiry and allowed myself to wade in the papers and wander, folder after folder, photographing items that piqued my interest. On my final day in special collections, I packed my belongings, exited the library, and took a deep dive into the photographs I snapped while researching onsite over copious amounts of earl grey tea. I’d selected a strange amalgam of political speeches, business and personal correspondence, notes and ephemera from various events. As I read, I reviewed my folders and took notes on what might be useful for my blaxploitation research. In the process, I gained a better idea of the extent to which Bond was interested in and engaged with popular culture. In this way, the collection did not disappoint.

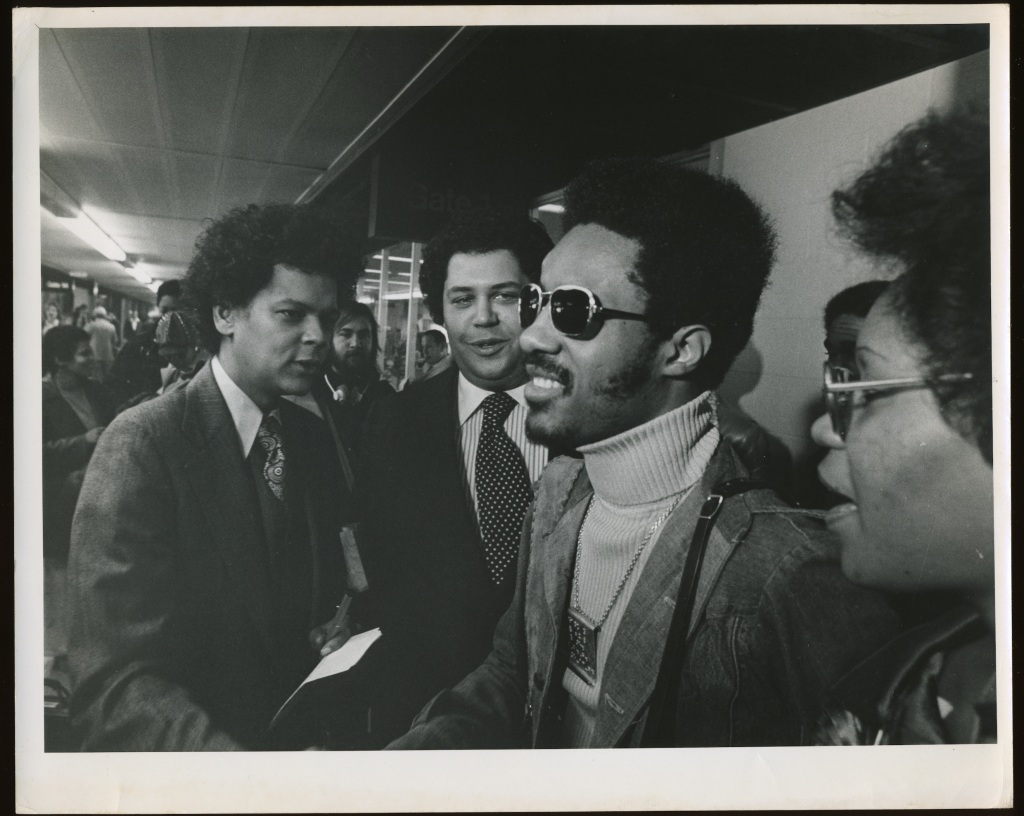

In 1961, Bond left Morehouse College to join the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), becoming a prominent member of the civil rights movement and organizing sit-ins and voter registration campaigns. Julian Bond Papers (MSS 13347, Box 120-121).

Below are a few excerpts from my time in the Bond papers. From these materials, another story emerges; one that takes me away from my initial inquiry yet delights me as a scholar invested in histories of Black culture. Through these documents, Bond becomes an unexpected vector in the 1970s Black popular culture landscape. With a curiosity I can’t shake I find myself asking, over and over, “Who is this guy?!”

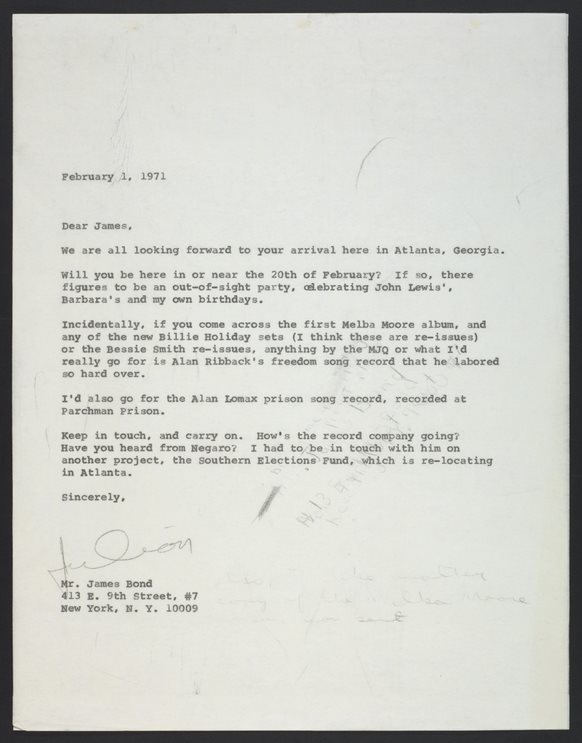

Julian Bond letter to his brother James about Black music. Julian Bond Papers (MSS 13347, Box 115, Folder 5)

Personal correspondence intrigues me. I’m nosey, so I relish opportunities to read correspondence by Black artists and activists. The significance of the communication, when viewed by a reader who is not the intended recipient can produce a host of reactions. But in this letter from Bond to his brother James, I relish the references to Black music. They give us insight into Bond’s musical taste, alerting us to the voices and sounds that filled his speakers. In this letter, Melba Moore, Billie Holiday, Bessie Smith and Modern Jazz Quartet share space in his personal collection. The sounds emanating from these records, divergent and capacious, allow us to eavesdrop (in a broad historical way) and take in the tempos, grooves, and lyrics that buoyed him. And should we desire to glean the albums that overtly befit Bond the activist, then Alan Lomax’s “prison song recording” or Alan Ribback’s Movement Soul (1967) are fitting references. So, if you can “go for” songs that remind you of Bond, this letter is a great place to begin.

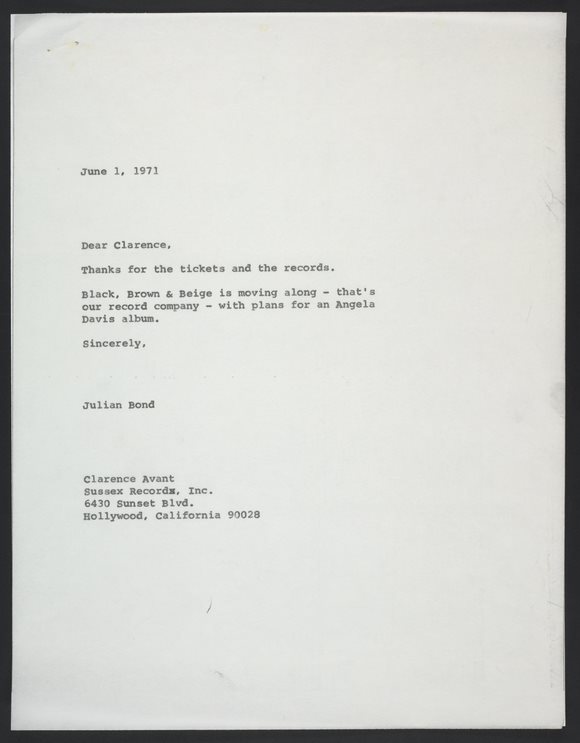

Letter from Julian Bond to Clarence Avant about starting theBlack, Brown, & Beige music record label. Julian Bond Papers (MSS 13347, Box 29, Folder 5)

Bond’s interest in music was also business-related. According to this letter to Clarence Avant, a.k.a. The Black Godfather, Bond was starting his own record label called Black, Brown & Beige. The name appears to be a reference to Duke Ellington’s 1943 composition. The song conveys the story of an African named Boola who is enslaved and brought to the United States. Across 20 minutes, the composition moves listeners from slavery to the emergence of the Blues. While I have yet to verify the existence of the record label, Bond’s desire to extend his activist tactics by releasing an Angela Davis record is especially interesting.

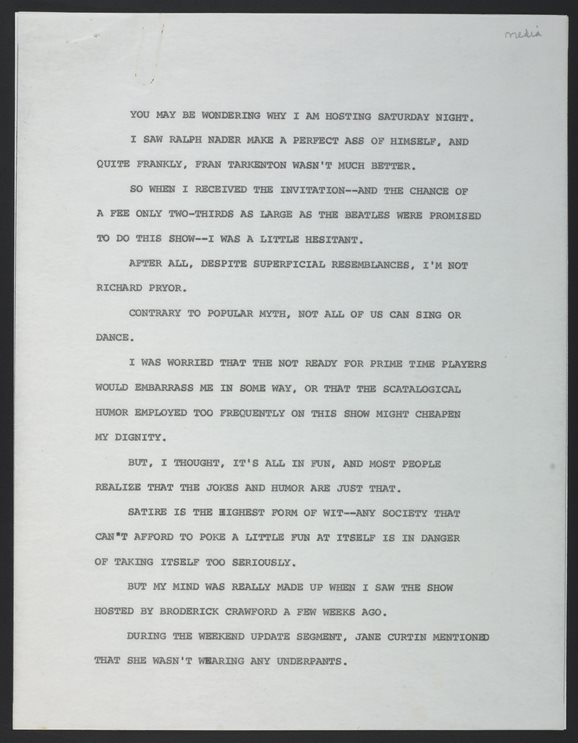

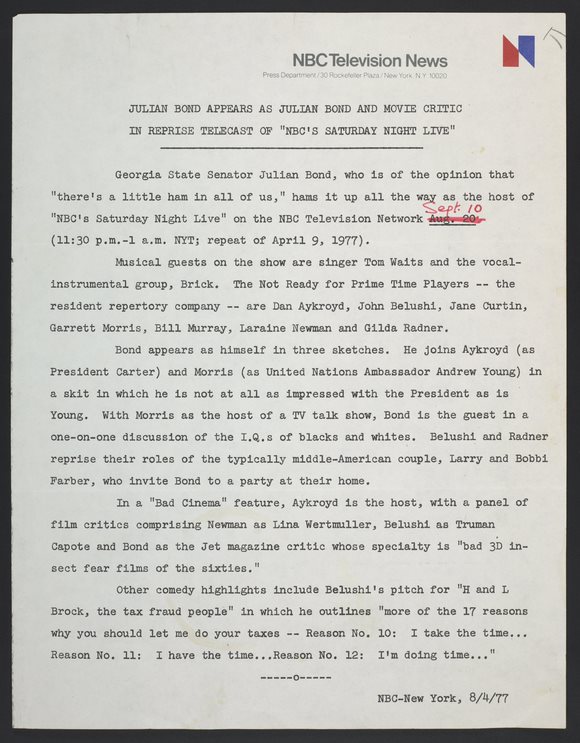

To get a glimpse of Bond’s relationship to humor, one need only look at the documents pertaining to a roast in his honor and his 1977 appearance on Saturday Night Live. The roast materials include a program listing featured speakers, as well as Bond’s script for the event. His barbs at attendees are laced with Black historical references, political commentary, and personal history. The Saturday Night Live materials include a typed draft on his opening monologue, scripts for various segments featuring Bond, and press documents.

Press release for Bond’s 1977 appearance on Saturday Night Live. Julian Bond Papers (MSS 13347, Box 6, Folder 22).

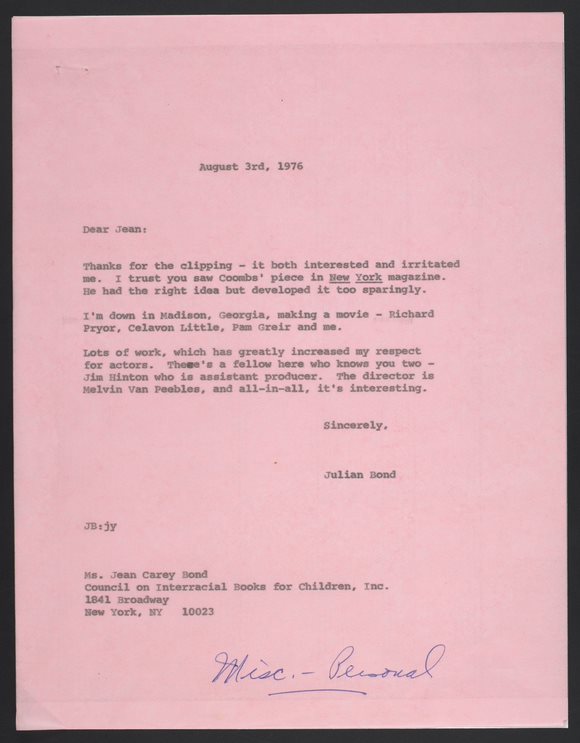

Letter from Julian bond to Jean Carey Bond about being in the film (Greased Lightning) with Richard Pryor and Pam Grier. Julian Bond Papers (MSS 13347, Box 28, Folder 1).

This letter from Bond to Jean Carey Bond is the closest I came to finding any meaningful connection between Bond and 1970s cinema. Blaxploitation was on the decline by this point, but I can’t help but wonder what conversations, jokes, arguments, and thoughts percolated between Bond, Pam Grier, Jim Hinton (a.k.a. James E. Hinton), Cleavon Little, Richard Pryor, and Melvin Van Peebles on the set of Greased Lightning (1977).

These materials give me insight into Bond, but they also remind me that there is so much more to be considered as I examine the cultural life of blaxploitation. Yes, there are iconic films like Superfly (1972) and Blacula (1972). Additionally, there are at least 200 more films that fall under the blaxploitation banner. But, for me, the term exceeds Junius Griffin’s definition. It encapsulates a cultural moment wherein Black artists, activists, and scholars wrestled over the attention and loyalty of Black audiences. And while my time in the Bond Papers did not bring me closer to uncovering the CAB, I take solace in Bond’s musical wants, his humor, and his prismatic Black humanity.

[1] https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/blaxploitation-films