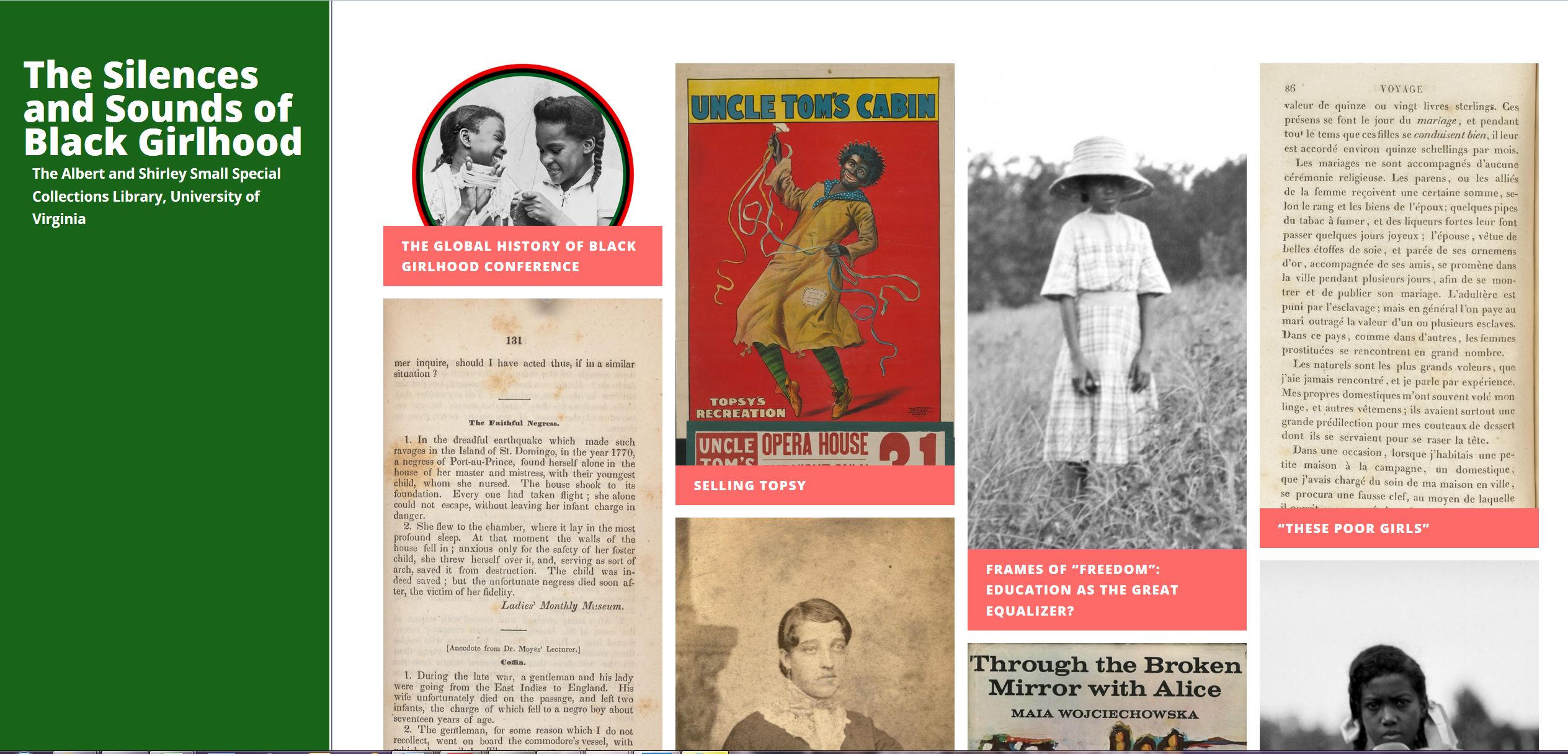

It is one thing to write a book. It is quite another for that book to receive widespread acclaim from one’s peers, as is the case with Literature Incorporated: The Cultural Unconscious of the Business Corporation, 1650-1850, the most recent work by John O’Brien, NEH Daniels Distinguished Teaching Professor in U.Va.’s Department of English. Literature Incorporated has been awarded the Louis Gottschalk Prize, presented annually “for an outstanding historical or critical study on the eighteenth century” by the American Society for Eighteenth Century Studies.

One need not be aware of the Supreme Court’s 2010 ruling in Citizens United or of Mitt Romney’s statement that “corporations are people” to benefit from a close reading of Literature Incorporated. Its subject is the corporation, “an abstraction that gathers up a long history of institutions and practices as varied as city governance, guild organization, state-sponsored colonial exploration, money lending, insurance, slave trading and university funding.” Its method is to trace the trope of incorporation in a wide range of Anglo-American texts, including “economic tracts, legal cases, poems, plays, essays, novels, and short stories.” And its goal “is to discover some of the ways in which language has ‘repeated’ the influence of the corporation to us, given it form in our imaginations.”

The U.Va. Library is proud to have earned a place in the book’s Acknowledgements. Indeed, most of the works discussed in Literature Incorporated (and many more that inform and amplify its arguments) can be found in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. Here is a modest selection, which we invite you to come explore in more depth.

King as corporation, comprised of the bodies of his subjects. Detail from the engraved title page to Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (London, 1651). (E 1651 .H658; Tracy W. McGregor Library of English Literature)

Literature Incorporated begins with Thomas Hobbes’ work of political theory, Leviathan (1651). Its famous engraved title page “offers an image of incorporation, of the people of a realm incorporated into the sovereign.” Although Hobbes viewed private corporations as potential rivals to government, O’Brien shows how Alexander Hamilton and John Marshall, among others, appropriated Hobbes’ language in support of corporations.

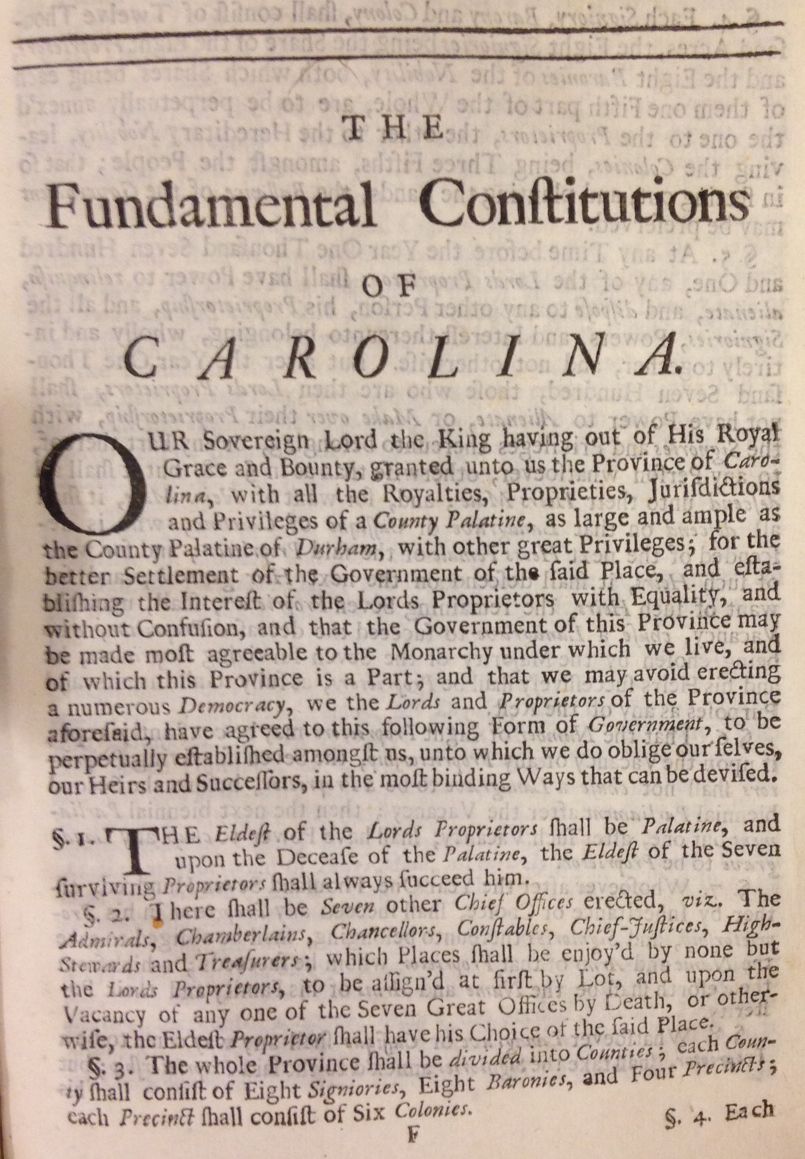

The Carolina Company’s vision for its American colony, drafted in large part by John Locke. The Two Charters Granted by King Charles IId to the Proprietors of Carolina (London, 1698). (A 1698 .G746; Tracy W. McGregor Library of American History)

Among the earliest English corporations were entities such as the Carolina Company, chartered by the sovereign to promote colonial settlement and trade. The philosopher John Locke was instrumental in developing the English mercantilist system, and O’Brien traces Locke’s crucial role in drafting the company’s Fundamental Constitutions (1669; final edition 1698), in which the Carolina proprietors envisioned the society they hoped to establish in the New World. Indeed, Locke’s empiricist philosophy permeates the document.

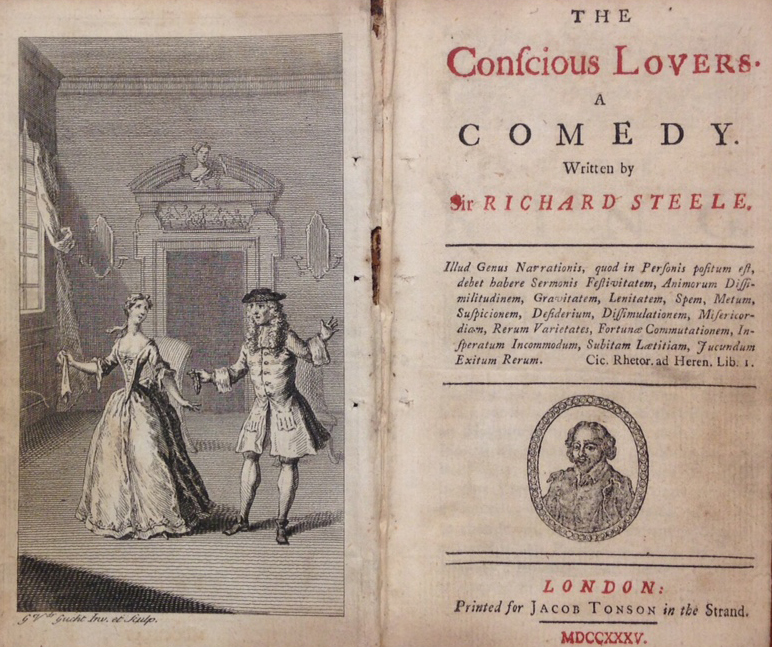

Frontispiece and title page to an early edition of Richard Steele’s The Conscious Lovers (London, 1735). (PR3704 .C66 1735)

Another such company, the South Sea Company, was at the heart of one of the greatest financial bubbles of all time, the South Sea Bubble of 1720. The speculative frenzy and resulting financial crash can be traced in many contemporary literary works, such as Sir Richard Steele’s play, The Conscious Lovers (1720). To the familiar plot lines of marriage and mistaken identity Steele added innovative complications concerning property rights. Steele also found himself accused publicly, through his involvement with the Drury Lane Company, of creating a theatrical equivalent of the South Sea Bubble to unfairly inflate the play’s ticket prices.

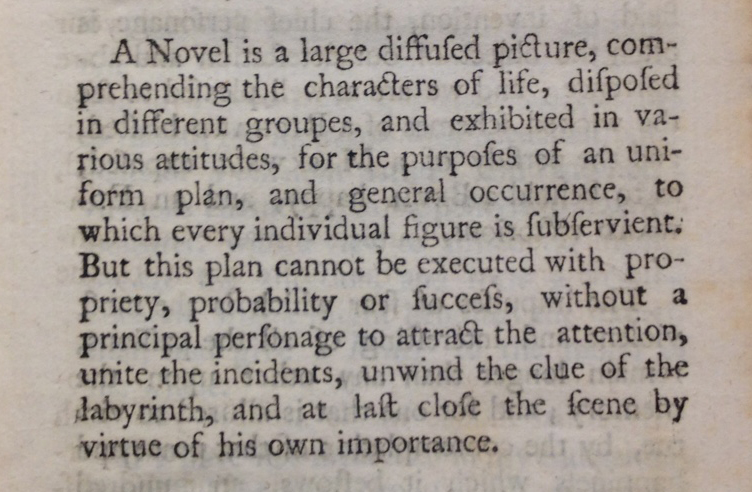

Tobias Smollett on why a novel needs a “principal personage,” from The Adventures of Ferdinand Count Fathom (London, 1753). (PR33694 .F54 1753 v.1)

The 18th century also saw the rise of insurance companies, which offered protection from risk and the fickle winds of divine providence. O’Brien demonstrates how contemporary English fiction’s “well-known investigations of risk and reward look different when they are read in the context of insurance history.” A perfect example is Tobias Smollett’s Adventures of Peregrine Pickle (1751), in which the plot is driven by Peregrine’s involvement with two different insurance policies. O’Brien also invokes Smollett’s famous statement, in the preface to The Adventures of Ferdinand Count Fathom (1753), that a novel requires “a principal personage to attract the attention, unite the incidents, unwind the clue of the labyrinth, and at last close the scene by virtue of his own importance.” In O’Brien’s words, the protagonist of a novel “resembles the corporation itself, a prosthetic person who helps bring the broader organization of a specific kind of economic activity into representation.”

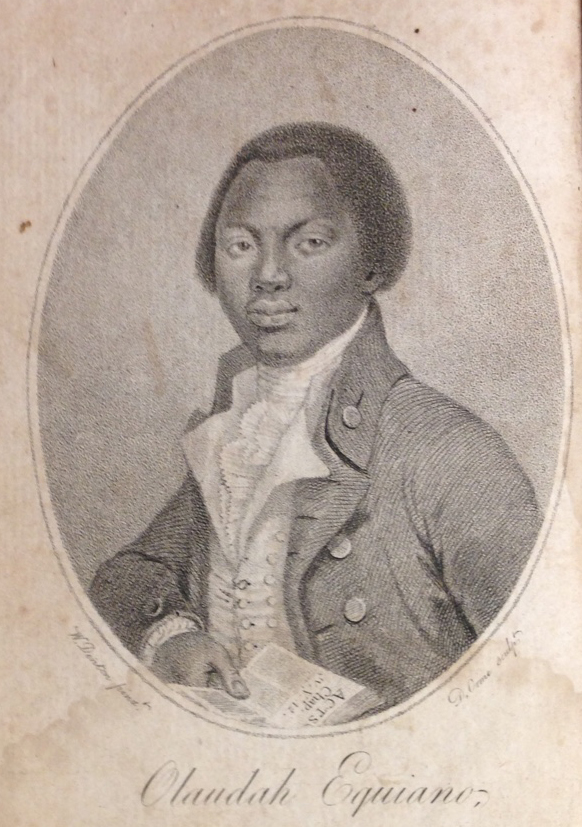

Frontispiece to The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano (London, 1789). (CT2750 .E7 1789; Gift of Mrs. Emily D. Kornfeld)

During the late 18th century, the London Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade waged a successful abolitionist campaign. O’Brien traces how “the society became a corporate voice that found itself emulating the very entities that it sought to attack,” for example, through its frequent use of an emblem featuring a supplicatory slave on bended knee. However, one key abolitionist publication—The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano (1789)—deliberately separated itself in form and content from this corporate voice, instead establishing itself “as a kind of corporate representative [of] ‘the African.’”

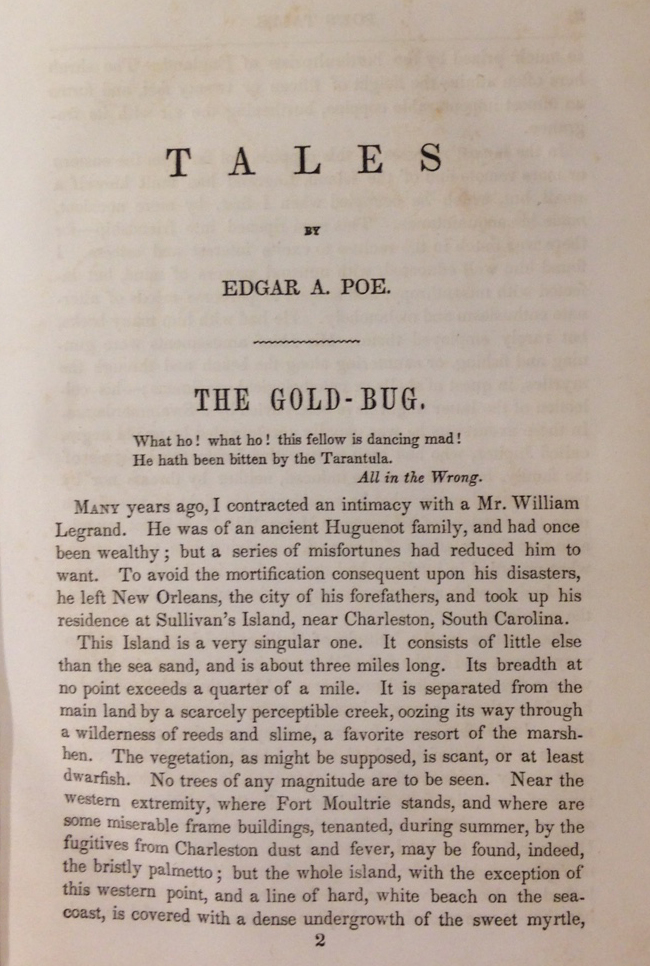

Beginning of Edgar Allan Poe’s story, The Gold-Bug, which leads off his Tales (New York, 1845). (PS2612 .A1 1845 copy 3; Gift of D. N. Davidson)

Literature Incorporated concludes with a discussion of Anglo-American literary responses to the fiscal and banking crises of the 1820s, 1830s, and 1840s. In particular, O’Brien offers a close reading of The Gold-Bug, the lead-off story in Edgar Allan Poe’s Tales (1845) and his most popular with contemporaries.

And to wrap up: hold the date! Another recent recipient of the Louis Gottschalk Prize—David Hancock, Professor of History at the University of Michigan—will deliver this year’s Thomas Jefferson Foundation Lecture on Wednesday, April 5, 2017 at 4:00 p.m. in the auditorium of the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. His talk, “The Man of Twists and Turns: Personality, Portrait & Power in the Re-Shaping of Empire,” concerns the 2nd Earl of Shelburne, the British prime minister who helped negotiate an end to the American Revolution. The lecture is co-sponsored by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation and the U.Va. Library.