This week, we are very pleased to feature a guest post from Special Collections Reference Coordinator Regina Rush.

“…and they stopped in my vision and looked up at me like I had something…to tell or something that needed to be seen or they wanted something to be remembered. So I kinda get this sense that it is time to understand what it must have been like.”

–African-American genealogist Tonya Groomes,

in the documentary Slavery by Another Name

My pursuit for information about the Rush branch of my family began shortly after I began working in the Special Collections Library in the late nineties.

What I knew about my family’s history could be summed up on a notecard. My paternal grandfather’s name was James Neverson Rush; he married my grandmother, Roberta Brooks; and they raised eleven children in a place called Chestnut Grove, a small unincorporated community in Esmont, Virginia, nestled in the Green Mountains of Southern Albemarle County.

An initial conversation with my father helped fill in a few gaps, but certainly not enough to satisfy my curiosity. I learned that my paternal great grandmother’s name was Ella Rush, but beyond that he knew very little of the Rushes’ history. With my appetite sufficiently whetted and wanting to know MORE! MORE! MORE! I embarked on a genealogical quest to “meet” my people. As one genealogist has put it, “When you search for your ancestors, you find great friends.”

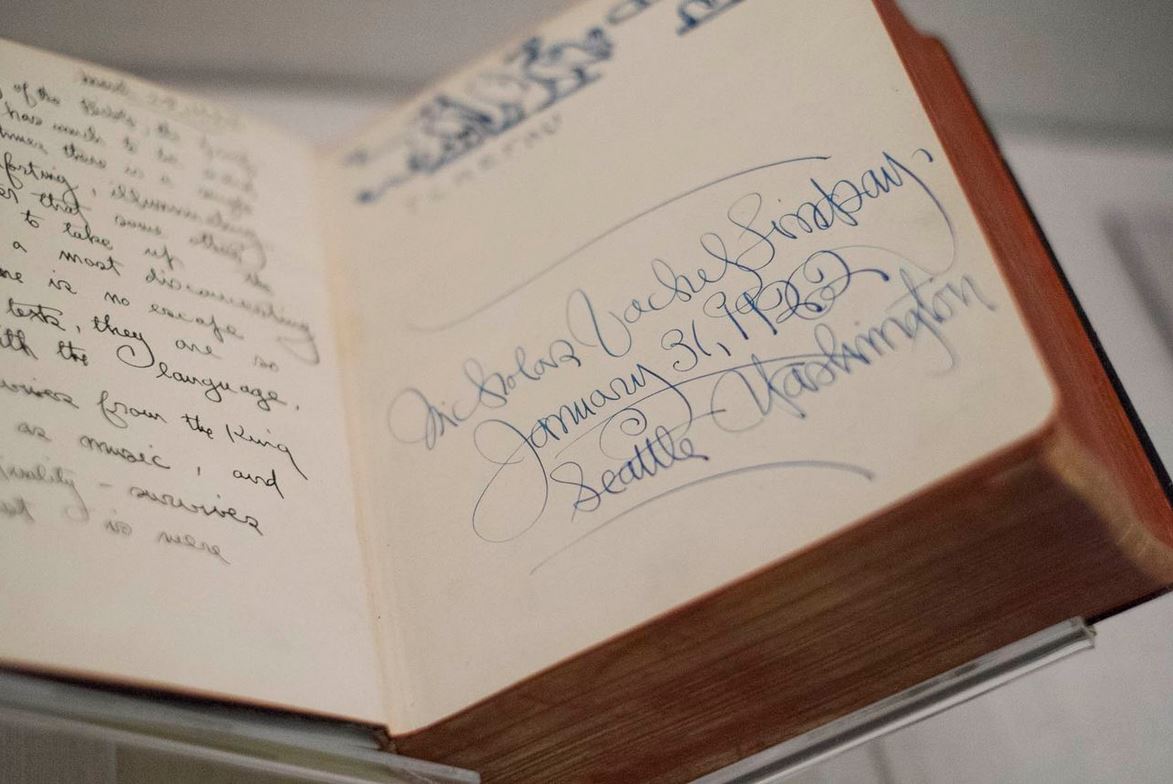

Well, not only did I find “great friends,” I found them under my feet at my job, one floor below in the stacks of the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library: they were my great-great grandparents, Nicey Ann Coles and Isham Rush.

Here’s how it happened

One Saturday afternoon while visiting my Cousin Gloria, our conversation turned to the subject of our family’s history. After sharing various family anecdotes, I asked her, “Cousin Gloria, do you have any idea what slaveholder owned our family?” I’d been researching my family’s history for several years, and despite numerous conversations with family members, visits to historical societies, and searching various genealogical databases, this key piece of family lore continued to elude me. So imagine my shock and elation when she responded in her slow, sweet, quiet voice, “Honey, our people were owned by the Rives Family.”

THE RIVES FAMILY??!!

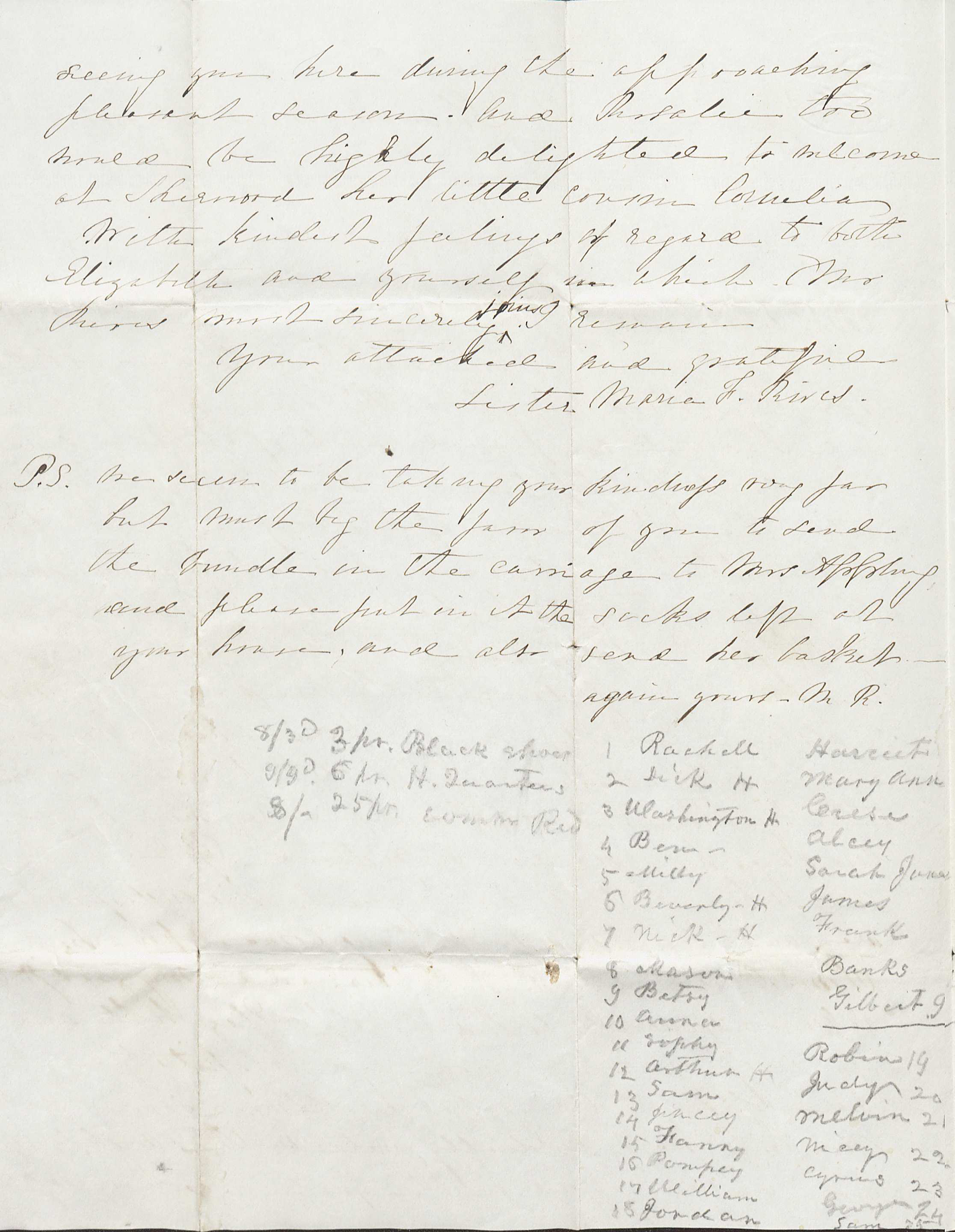

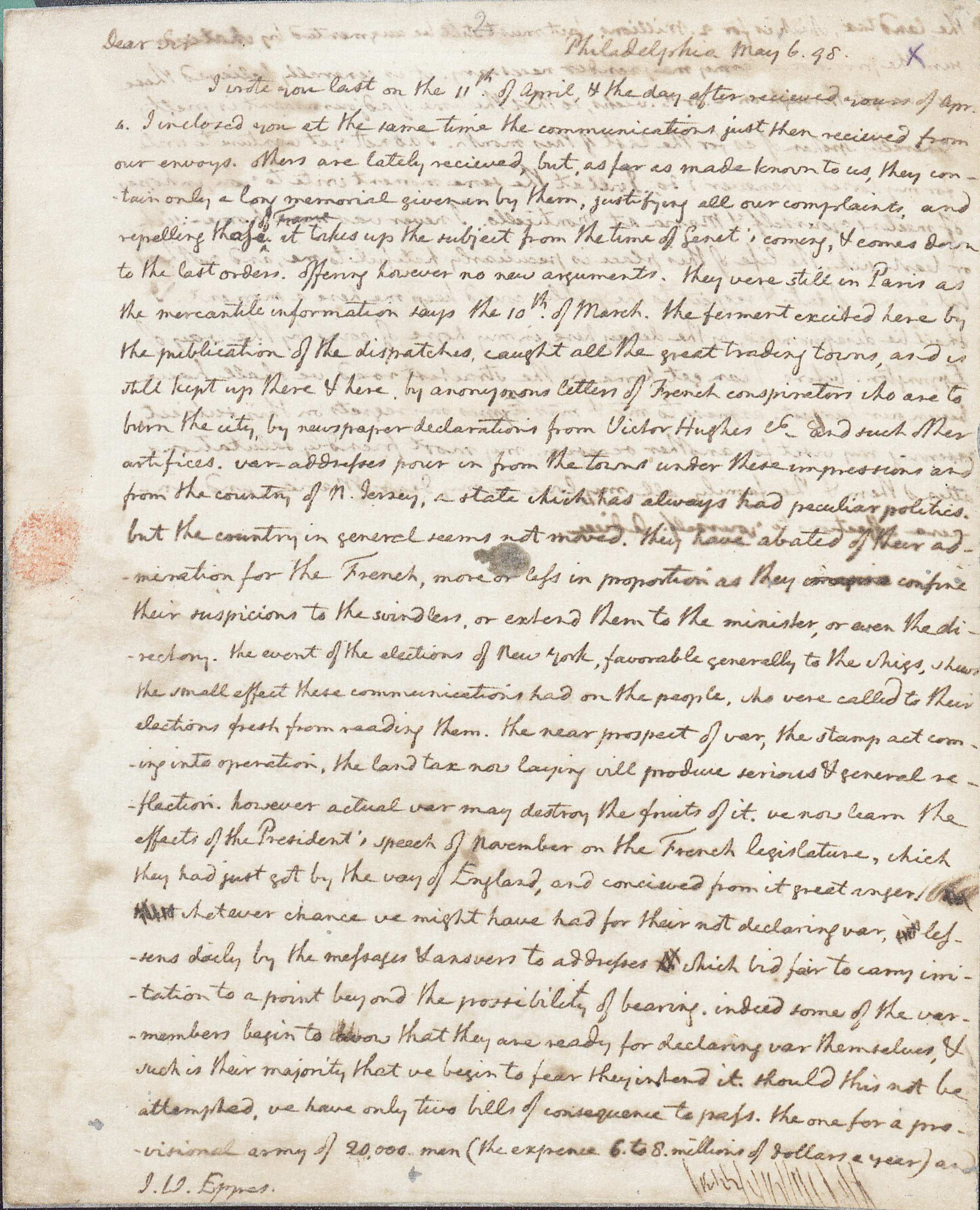

As in the, Special Collections holds numerous collections of this family’s papers, Rives Family? Over the course of the next several weeks, I painstakingly worked my way through collection after collection of Rives papers held at Special Collections. One day, while searching through the papers of a Rives named Robert, I happened upon a letter dated March 24, 1851 to Robert Rives from his sister-in-law, Maria, discussing a recent visit to his home, Oakland, and the declining health of his brother George. I quickly skimmed the contents of the first page and flipped it over. My eyes were immediately drawn to a list of thirty-four names written at the bottom of the page. Excitement slowly began to build in me. Almost afraid to breathe, I quickly scanned the list. PAYDIRT! Number 22 on the list was the name “Nicey.”

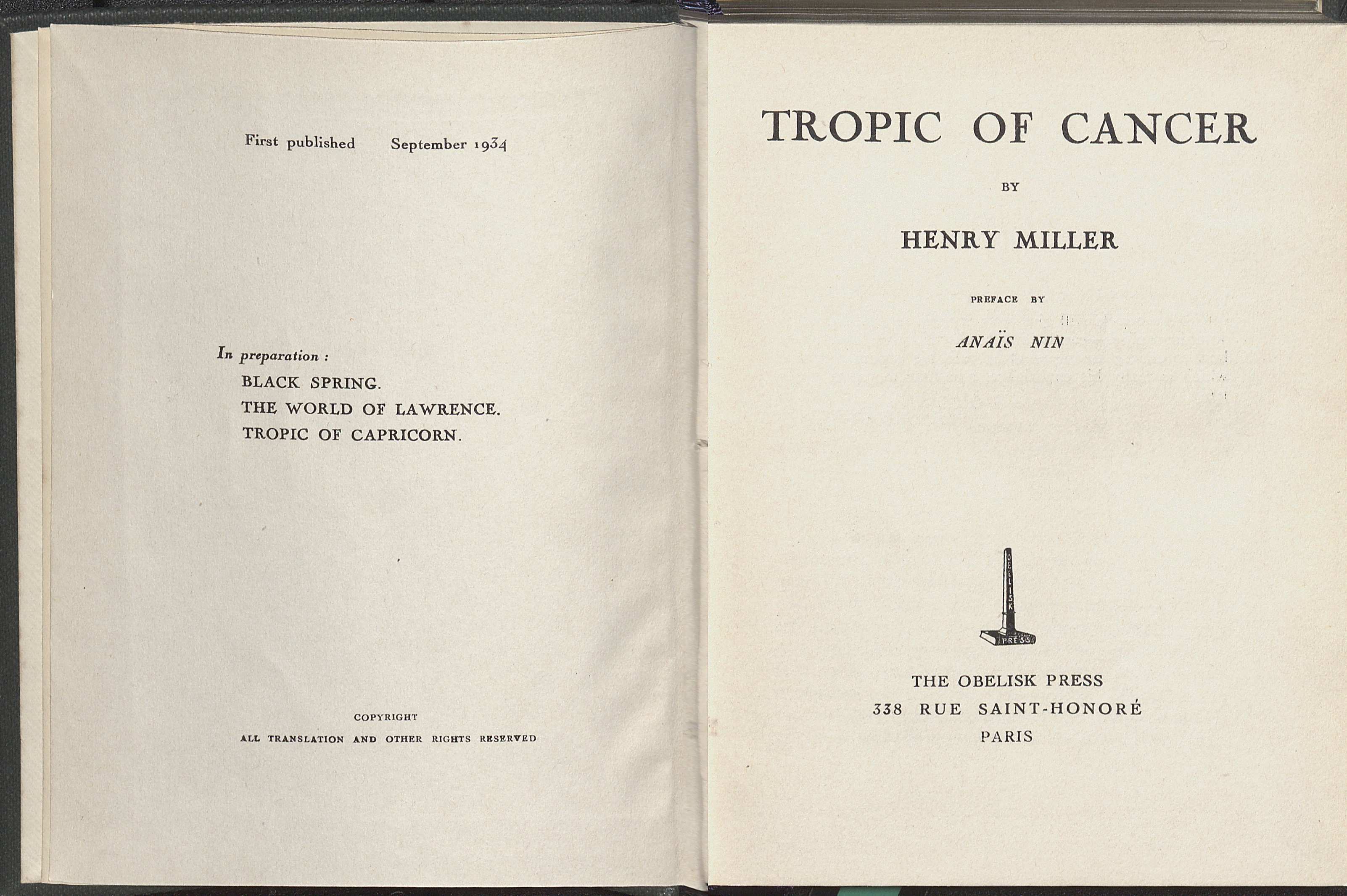

. In the letter Maria writes about a recent visit to Rives and his family at their home called Oakland, and the declining health of his brother George. The contents of the letter has no connection to the list found at the bottom of page two. Rives uses the bottom of the page as scratch paper to list the names of 34 of his slaves and supplies purchased for them. The number 22 on the list is my great-great grandmother, Nicey Ann Coles. (MSS 4289: March 24, 1851 letter from Maria Rives to her brother-in-law, Robert Rives Jr. Image by Regina Rush)

Uncovering the stories of Nicey Coles Rush and Isham Rush

Nicey Ann Coles was born circa 1823 in Nelson County, Virginia, most likely on one of the several plantations owned by Robert Rives, Sr. (1764-1845), a wealthy international merchant, who farmed tobacco and wheat, but most importantly owned both my great-grandparents. Nothing is known about Nicey’s parents. Information provided on her 1868 marriage license lists only her father’s last name, which is “Coles.” For reasons unknown, her mother’s name is not listed at all. In all likelihood, both she and her parents lived as slaves on Oak Ridge, the 2555 acre Nelson county, Virginia, estate owned by the Rives family. Oak Ridge was originally an 800-acre tract owned by Colonel William Cabell (1730-1798). Cabell later gave it as a gift to his daughter, Margaret Jordan Cabell, and his son-in-law, Robert Rives, Sr. (1764-1845).

Very little is known about Isham Rush, Nicey’s husband: his birth and death dates and parents’ names remain a mystery. Isham was possibly born enslaved on the Rives Plantation in South Warren, Albemarle County. Census records of his children confirm that Isham was a native Virginian. Three of his children record him as their father on their marriage licenses. By 1868, he disappears from public record. His oldest child was his namesake (spelled “Isom” in the 1870 census) and down through the generations some variation of the name continues to be used. Even today, more than a 150 years later, Isham remains in the family: one of my paternal uncles was named John Isom Rush.

How long Nicey lived and worked on the Rives’ plantation in Nelson is unclear. Records reveal that she was relocated at some point to one of the Rives’ Albemarle County plantations, referred to as the South Warren Estate. This estate was originally owned by Robert Rives Sr., but upon his death it passed on to his son Robert, Jr. (1798-1866). Robert, Jr. was born in Nelson County in 1798. He represented Nelson County in the House of Delegates during 1823-1829 and afterward moved to Albemarle County, eventually becoming one of the wealthiest men in Virginia before the Civil War. The 1860 census record his assets at $280,000; most of his wealth was lost during the Civil War.

Records reveal that my great-great grandparents had a longstanding relationship of more than 13 years on the South Warren Estate and managed to raise a family–as much as one could within the restrictive confines of slavery. Their children’s names were Ella (my great grandmother), Cecelia, Louisiana, Lucy, Isham, Neverson and Fleming. Some evidence suggest they had as many as ten children, but more research needs to be done before this can be confirmed. The Rush families of Chestnut Grove appear to be descended from two of their children, Ella and Louisiana Rush.

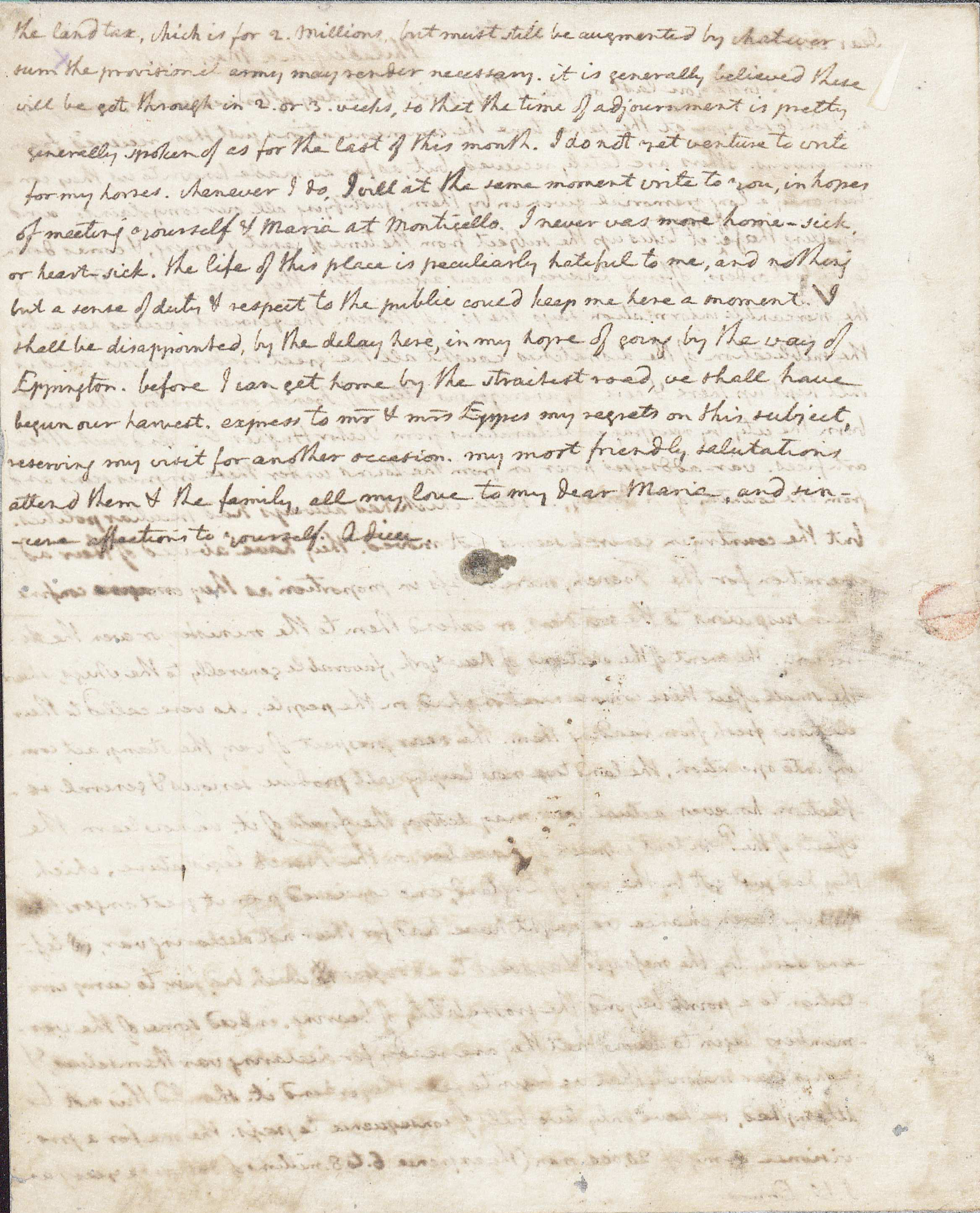

The following images were obtained from several plantation records of Robert Rives and provide brief snippets of information concerning Nicey and Isham’s existence at the South Warren Estate, in Warren Virginia.

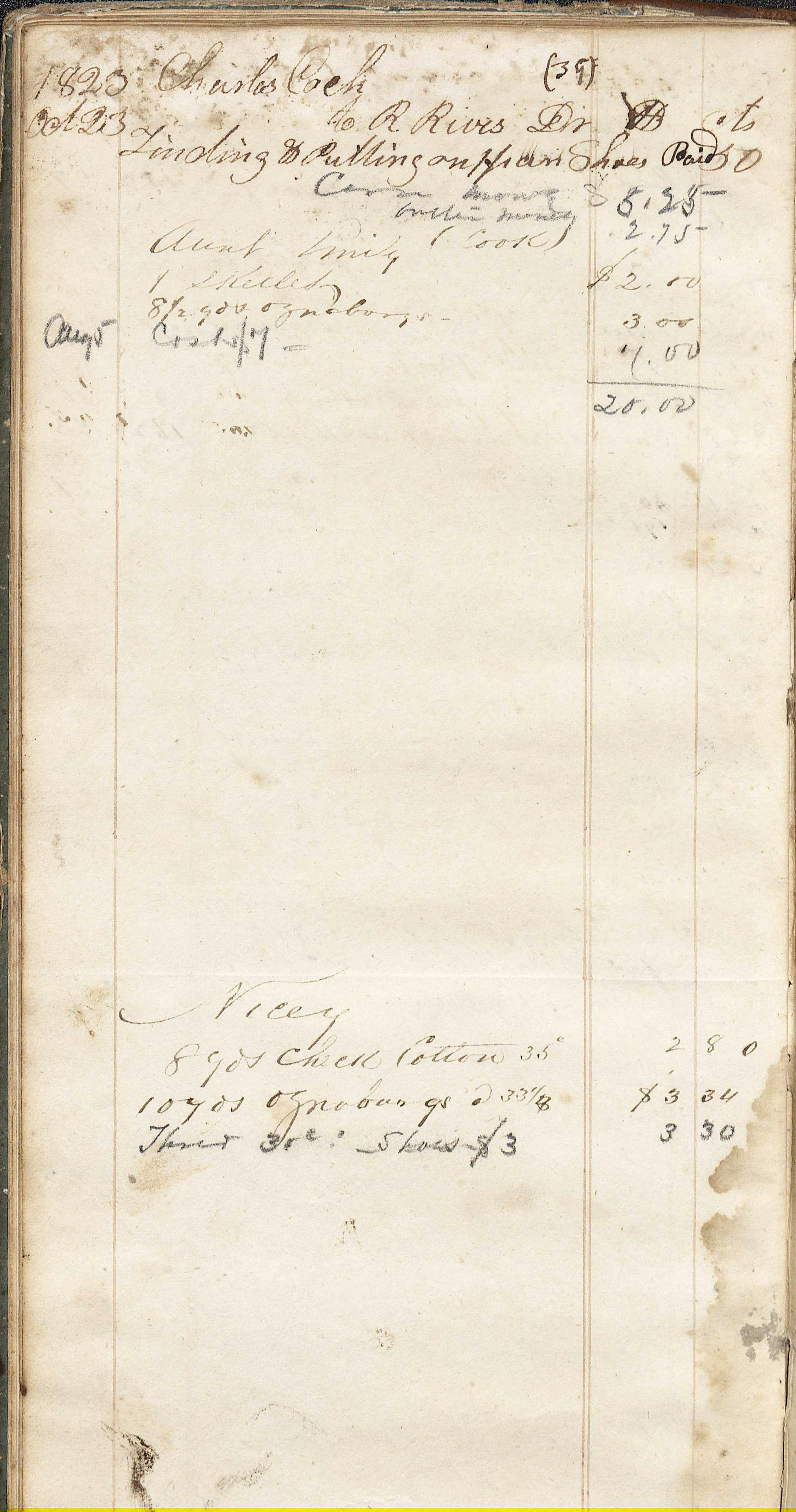

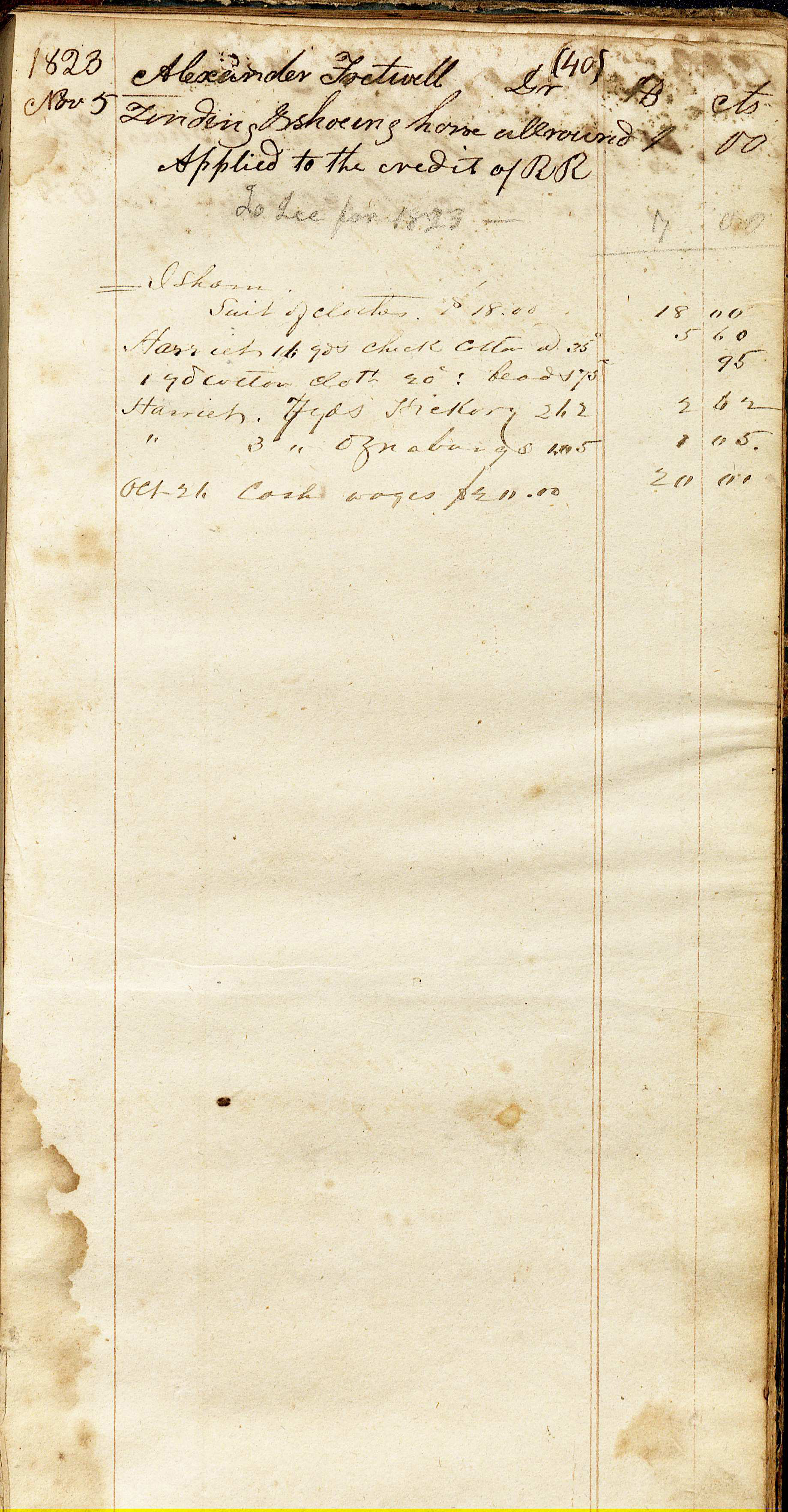

An account book held by the Special Collections Library shows that Rives purchased eight yards of check cotton and ten yards of Osnaburg fabric for Nicey for $6.14. On the opposite page of Nicey’s entry is written the name Isham and under the name, “suit of clothes $18.00” (see next image). While the page includes other entries as early as 1823, these entries likely date to the 1840s.

(MSS 4655: Robert Rives Blacksmith Shop Account Book, 1823; 1843-1846. Image by Regina Rush)

Opposite Nicey’s entry is written the name “Isham” and under the name “suit of clothes $18.00.” (Image by Regina Rush)

A discovery in Scottsville

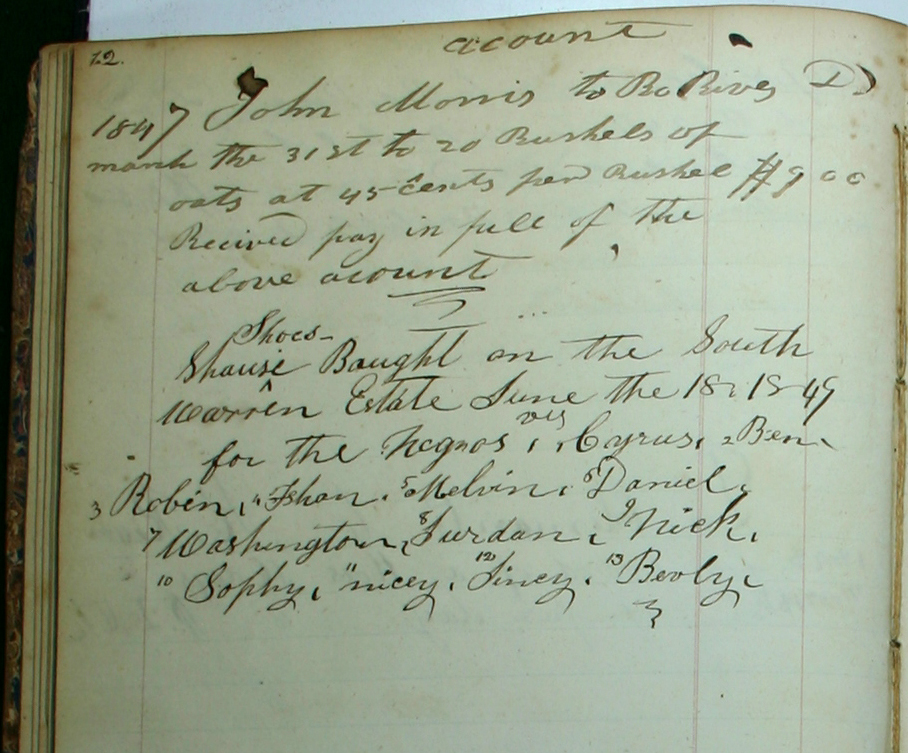

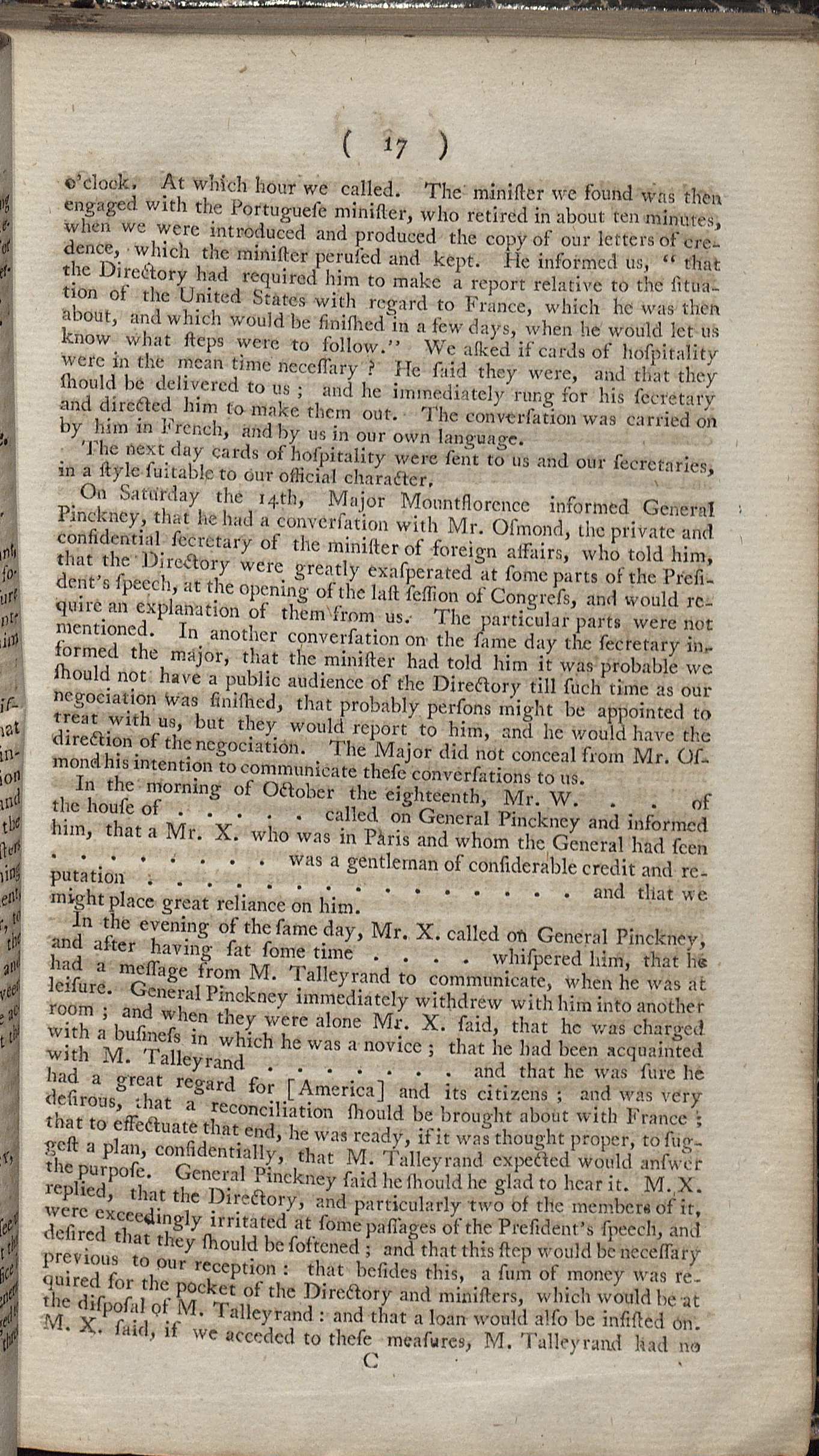

Things got even more interesting when I contacted the Scottsville Museum, after discovering online that they had Rives-related papers. First, I found a relevant entry in a business ledger of Robert Rives, Jr., which is owned by the Scottsville Museum. It lists Rives’ purchase of shoes for some of his slaves. Among the names on the list are my great-great grandparents, Isham Rush and Nicey Ann Coles. It reads “Shause (Shoes) bought on South Warren Estate June 18, 1849 for the negroes, vis Cyrus, Ben, Robin, Isham, Melvin, Daniel, Washington, Jurdan, Nick, Sophy, Nicey, Jincey, Bevly.” (Robert Rives Ledger 1846-1863. Page 12, Image 8, Scottsville Museum, Scottsville, Virgina).

Entry from the business ledger of Robert Rives, Jr. Rives lists shoes that he purchased for some of his slaves. Among the names on the list are my great-great grandparents, Isham Rush and Nicey Ann Coles. (Robert Rives Ledger 1846-1863. Page 12, Image 8, Scottsville Museum, Scottsville Virginia)

The year 1851 was an eventful one for Nicey. In January 1851, she gave birth to Ella Rush, my great grandmother. Another document indicated that sometime later that year, she attempted to escape from South Warren.

Wait, my great-great grandmother ATTEMPTED TO ESCAPE!!!!!

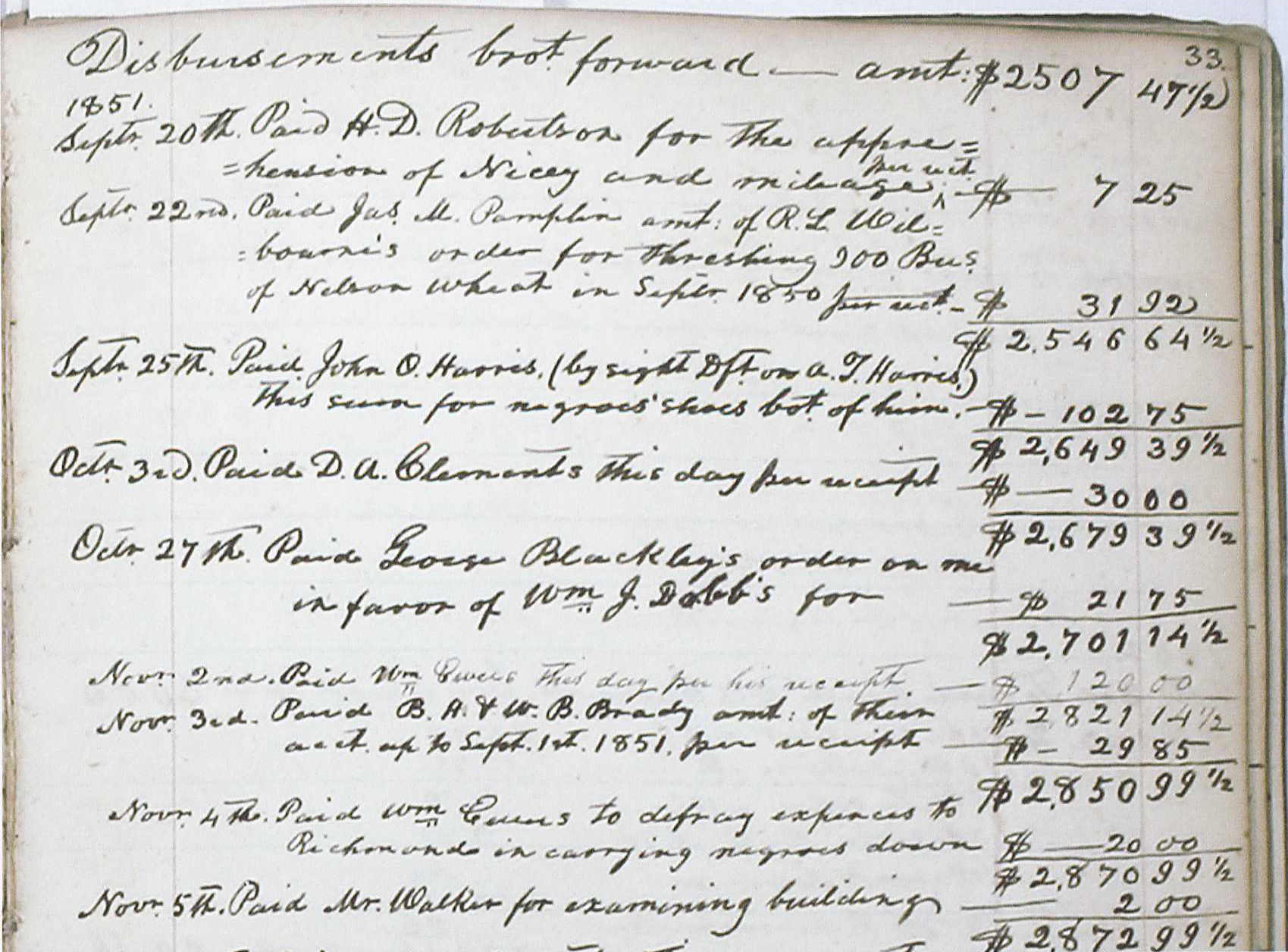

A September 20, 1851 ledger entry made by Rives reveals that Nicey’s attempt was not successful: “Paid H.D. Robertson for the apprehension of Nicey and mileage there with $7.25.” I wondered at this series of events. Ella is listed in census records as the oldest of Nicey’s children. Perhaps there is a correlation between the two events–her pregnancy and her escape. But no documentation has been uncovered to support this.

Nicey’s apprehension is documented on the second and third lines of this page. (Robert Rives Ledger 1846-1863. Page 33, Image 18, Scottsville Museum, Scottsville Virginia.)

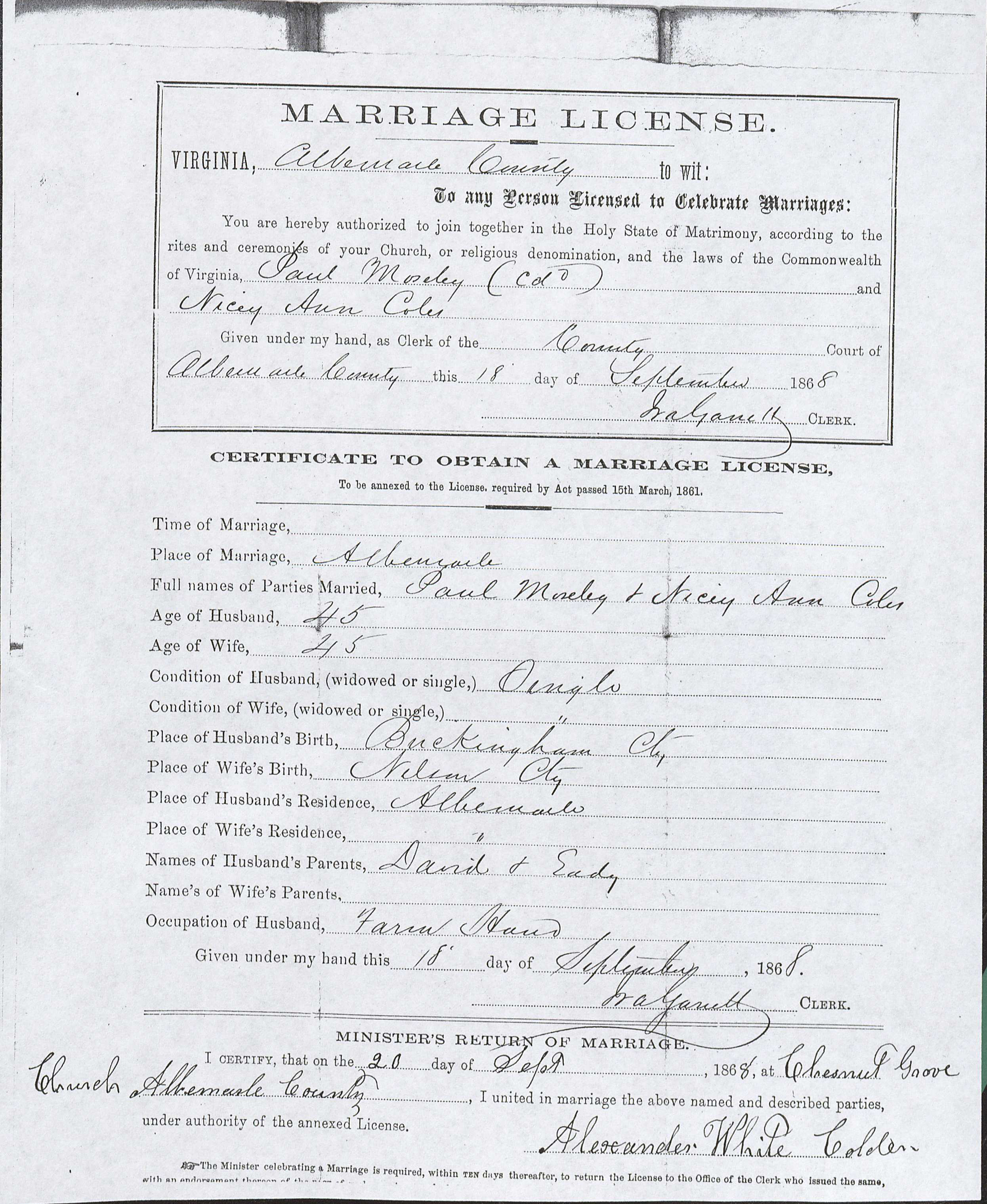

Albemarle County Courthouse records helped me understand what happened to Nicey after the Civil War, and after Isham Rush disappeared from public record, presumably deceased. On September 18, 1868, Nicey and a man named Paul Moseley went to the Albemarle County Courthouse to obtain a marriage bond. Two days later, on September 20, 1868, they were married at the Chestnut Grove Church in Esmont, Virginia by a minister named Alexander White.

Marriage license of Nicey Ann Coles and Paul Moseley, September 18, 1868. Courtesy of the Albemarle County Courthouse, Charlottesville, Virginia, 22902 (Image by Regina Rush)

By 1870 Nicey was 47 years old, still residing in Warren, Virginia. She shared a home with her husband, 47-year-old Paul Moseley, her 12-year-old stepson Paul Jr., and all seven of her children. Ella, 20; Cecelia,18; Lucy, 16; Louisiana, 3; Isham, 13, Neverson, 11; Fleming, 7; and her granddaughter Sophronia, Ella’s 11-month-old daughter. The 1870’s saw Nicey’s daughters Cecelia and Lucy married and out on their own. Her son and step-son had either died or migrated to another area by 1880.

The 1880 census shows that Nicey and her family had moved to Scottsville, near to Cecelia. The census reveals that her husband was still alive and only three of her children remained in her household–Isham, Fleming, Louisiana. Nicey died sometime between 1880 and 1900.

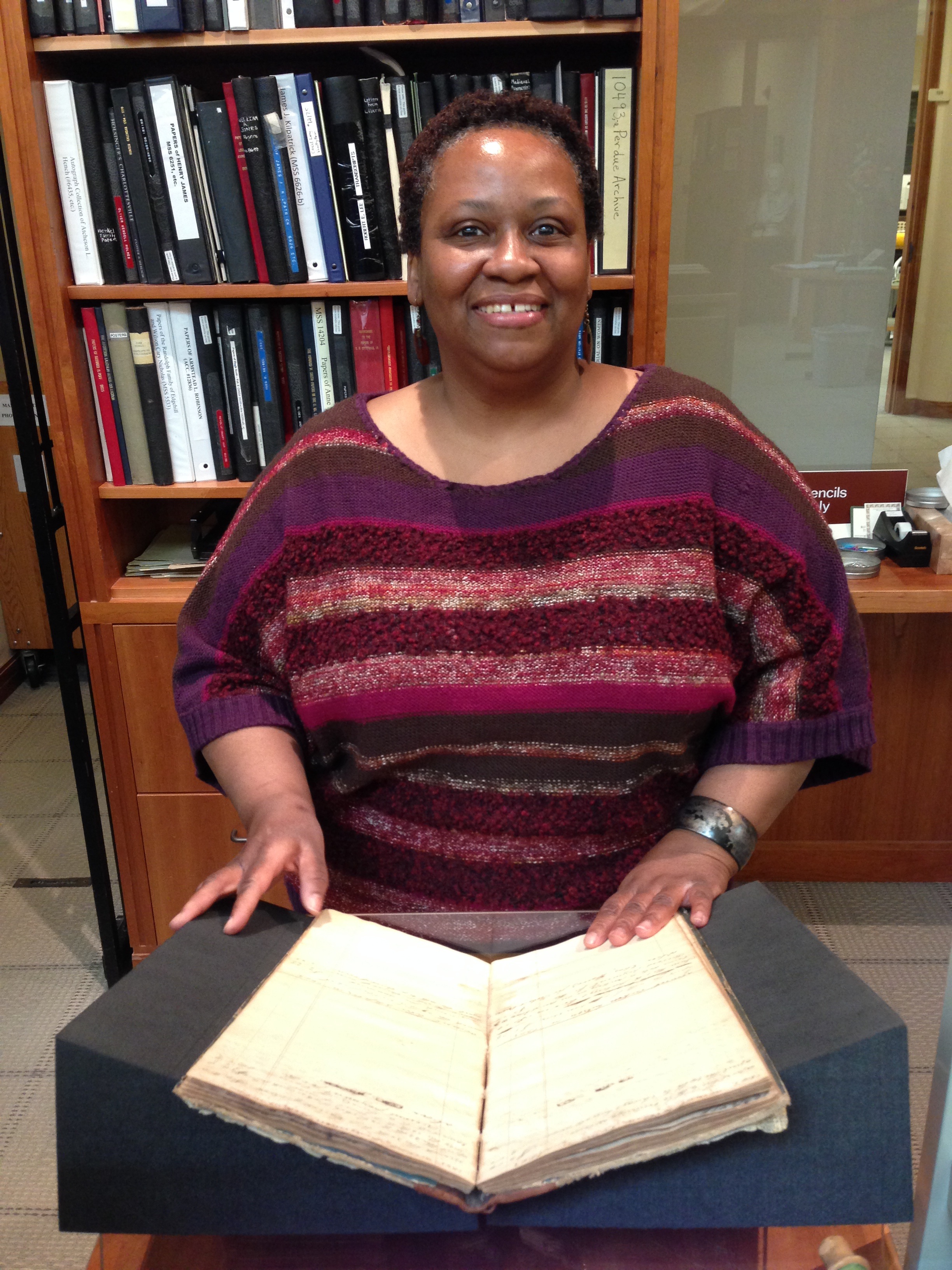

From the first time I looked at the 1870 census record for the Rush line of my family, I felt compelled to learn their stories. Over more than fifteen years of digging into my family’s ancestry, I have amassed quite a bit of raw data that screams out to be put in some sort of form that tells their story. Notes from Under Grounds proved to be the perfect launching pad. It is my honor and privilege to tell the story of my great-great grandparents. I dedicate this blog post to them, the Patriarch and Matriarch of the Albemarle County Rushes of Chestnut Grove. World, I introduce to you Nicey Ann Coles and Isham Rush, my new friends.

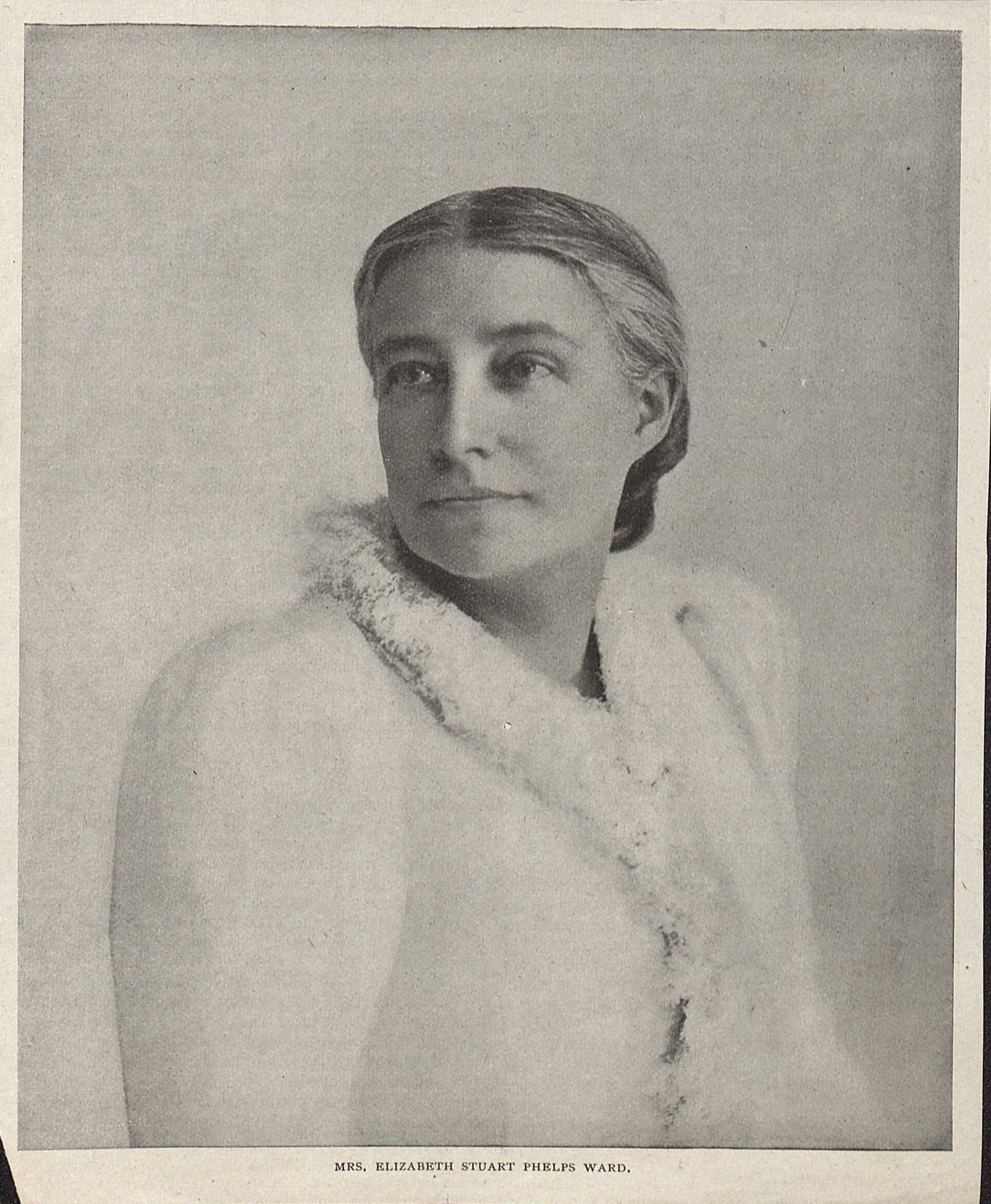

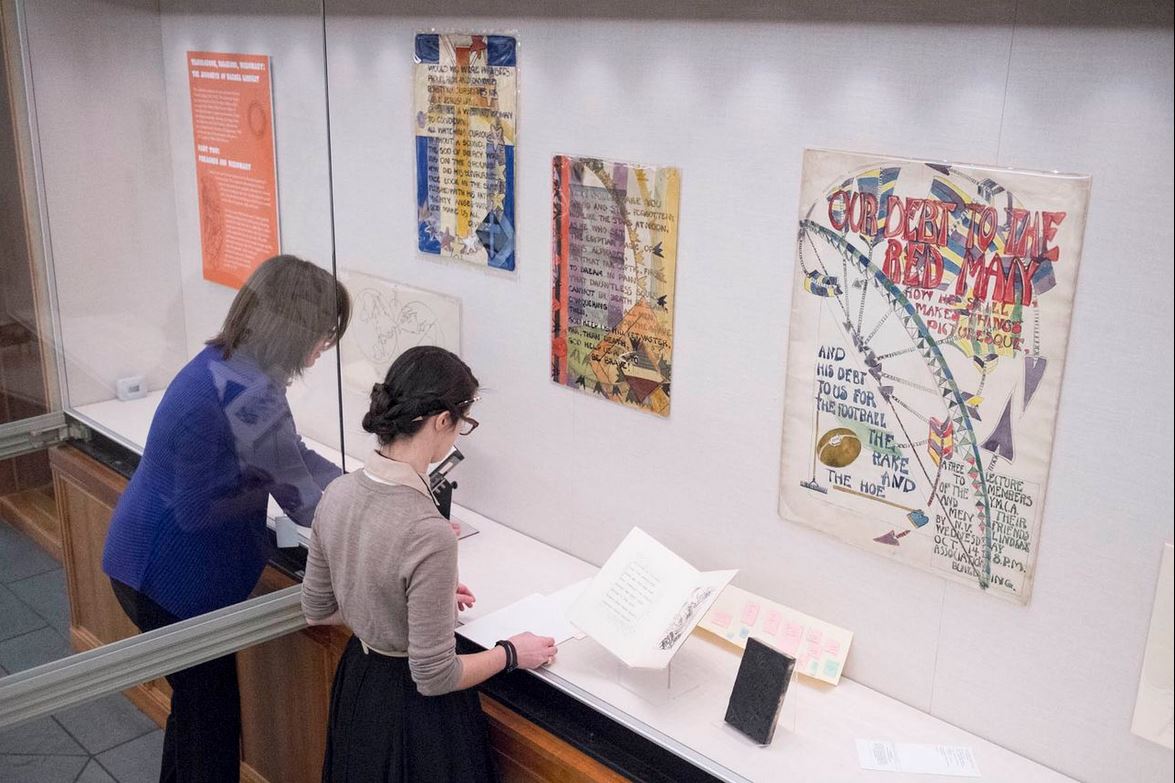

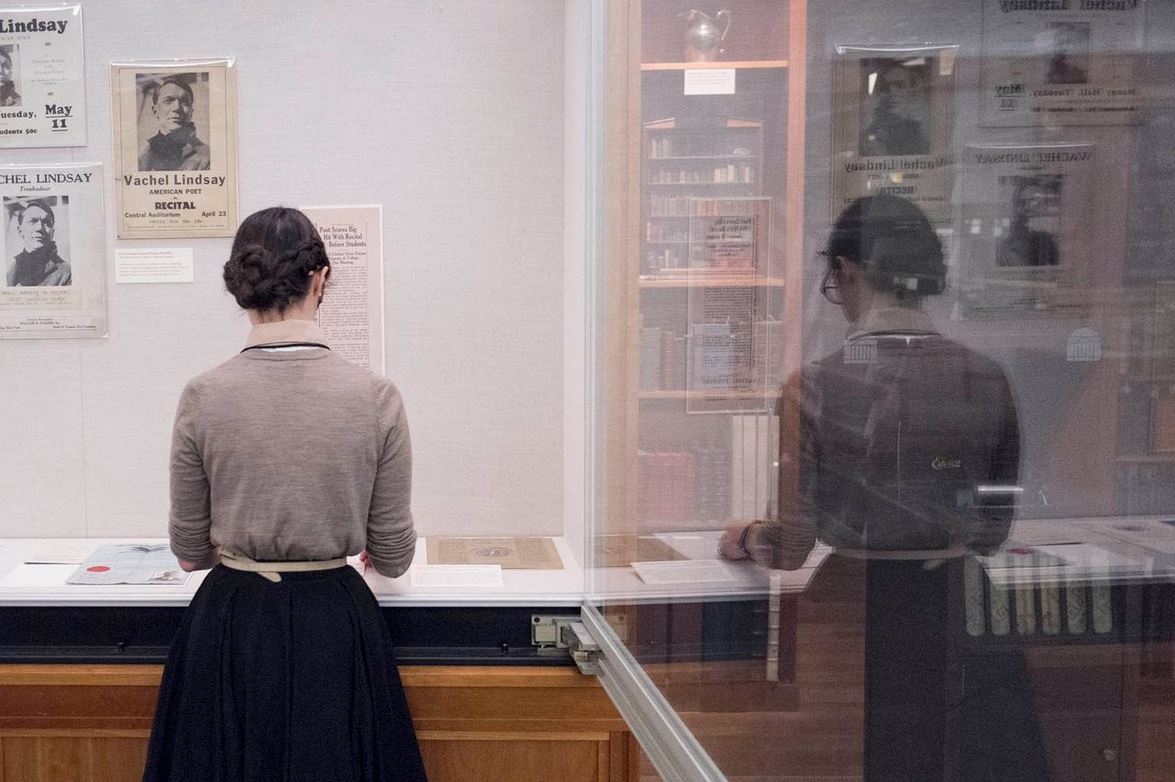

Regina Rush Special Collections Reference Coordinator, March 26, 2014. She holds one of the Rives ledgers that has helped her recover her family history. (Photograph by Molly Schwartzburg)

Special thanks to the Scottsville Museum and the Albemarle County Courthouse for permission to share images from their collections.

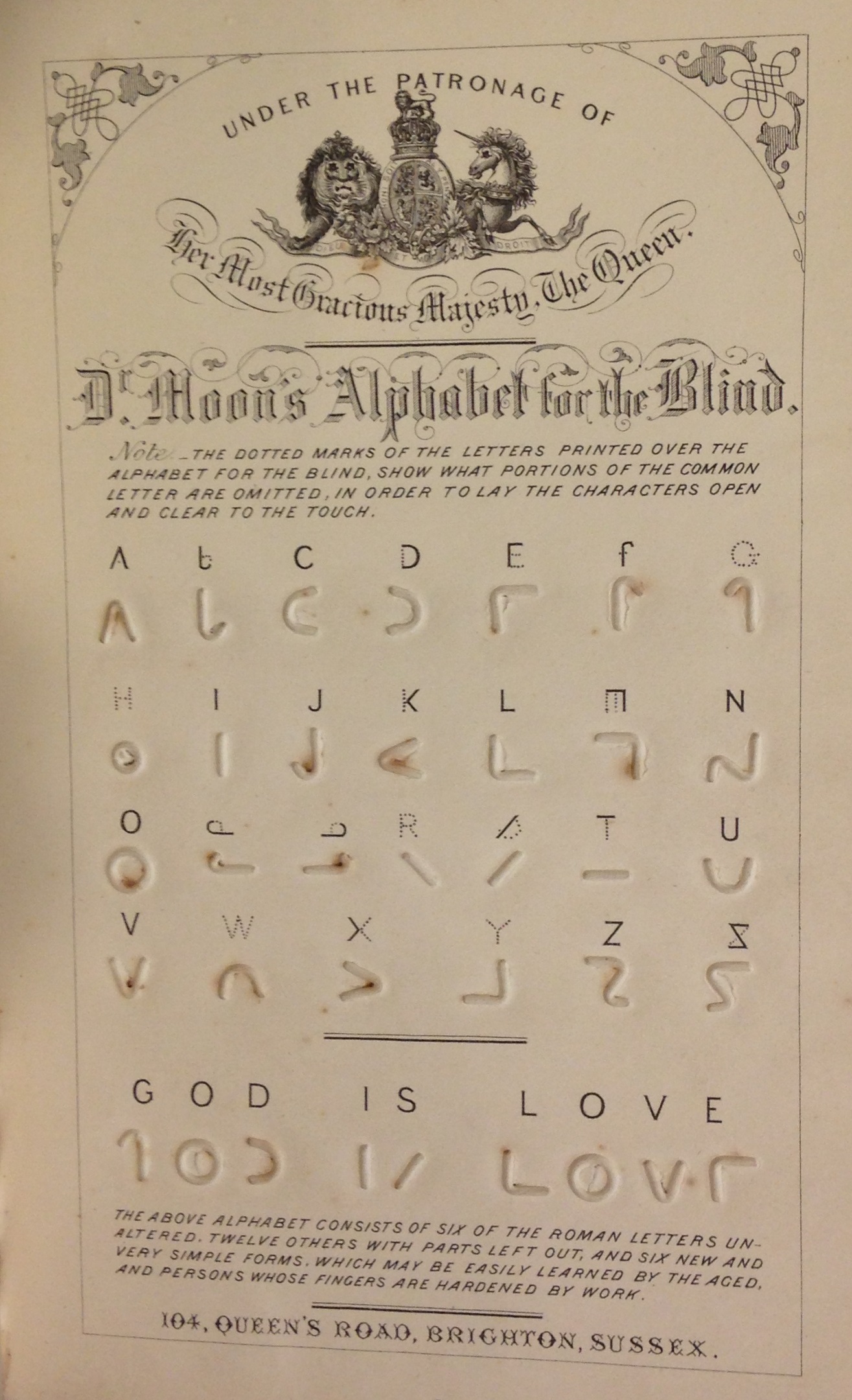

![A manual alphabet from a collection of ornamental alphabets, Recueil d'alphabets, dedié aux artistes (Paris & New York: L. Turgis jeune, [ca. 1845?]. (NK3600 .B65 1845)](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/D7.jpg)