This week we are pleased to feature a guest post by researcher Dr. Candace Epps-Robertson, who teaches in the Department of Writing, Rhetoric, & American Cultures at Michigan State University. Dr. Epps-Robertson worked with our collections remotely, requesting digital images of materials, mostly from the voluminous papers of Senator Harry Flood Byrd.

As a scholar of rhetoric during the Civil Rights Movement the questions that guide most of my research are usually quite simple: How were arguments made and how did they circulate? These questions drive my work in the area of Virginia’s Massive Resistance period. My research into this bleak moment of Virginia’s history comes as a result of my work on Prince Edward County, Virginia’s five-year public school closures in resistance to Brown vs Board of Education (1954). While Massive Resistance, on the books at least, subsided after 1959, Prince Edward persisted through the refusal to integrate public schools. To better understand how local leaders were able to close schools I trace and examine how segregationists introduced discourse to strengthen connections and mobilize efforts for an audience supportive of the notion that the preservation of segregation was a civic duty. One of the architects of the discourse of Massive Resistance was Senator Harry Flood Byrd whose papers exist in The Albert and Shirley Small Collections.

The late Senator Byrd had a thirty-three year political term in the Commonwealth, serving as governor from 1926 until 1930 and senator from 1933 until 1965. In many ways his position on segregation was no different from that of other supporters; however the power base he held in Virginia’s government secured him a larger audience. My quest to understand the history, context, and arguments made by Byrd brought me to this archive.

Thus far, my research in Byrd’s papers has all been done remotely. As a researcher whose work depends quite heavily on archival work, working entirely from digital copies from U.Va.’s Special Collections was a new adventure for me. I enjoy both the physical hunt for documents as well as the serendipity of the archive, but the detailed finding aid, and helpful assistance of the library’s staff, has made the long-distance research move with ease.

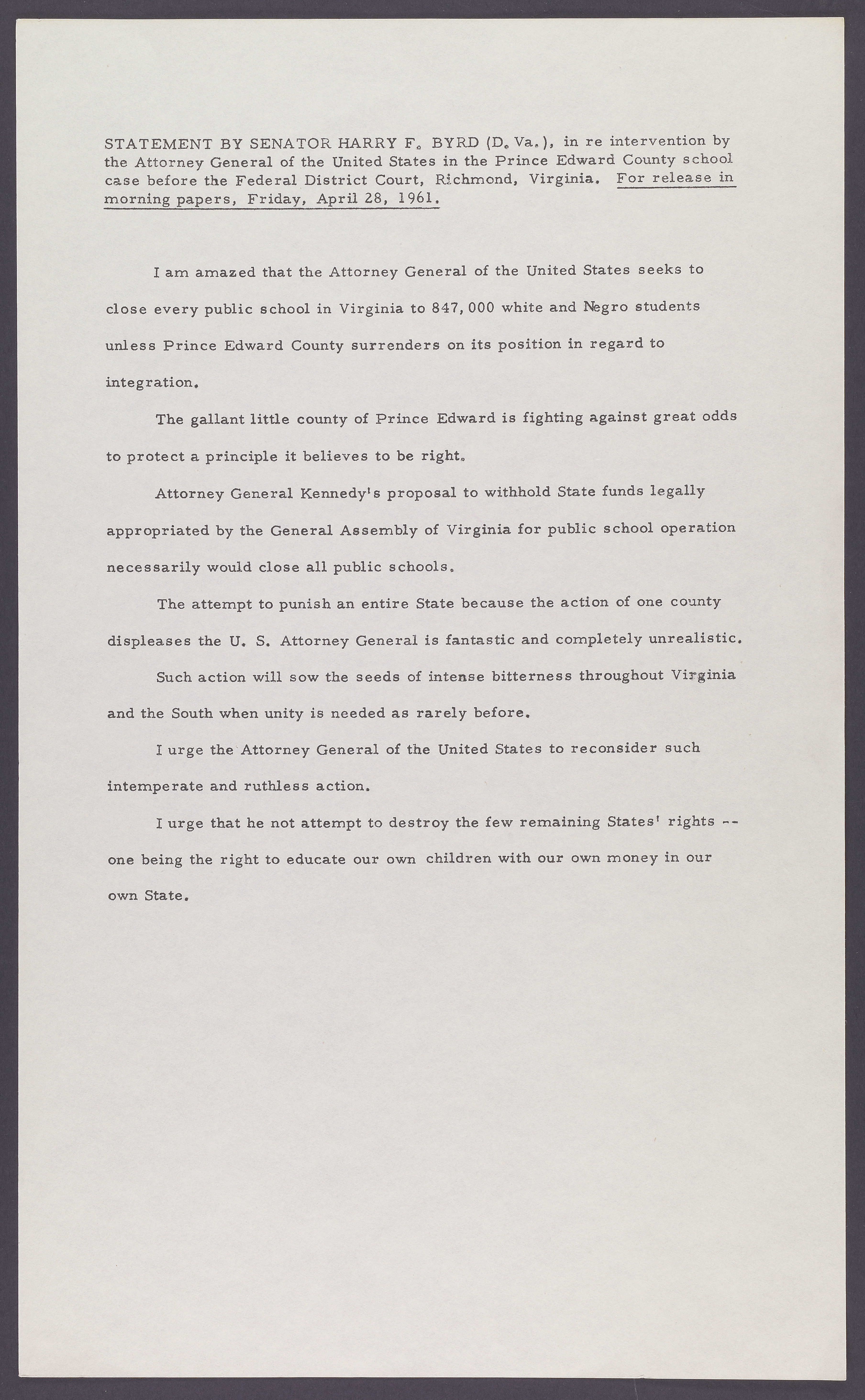

One of the many documents that has helped me understand Byrd’s means of crafting arguments is his April 28, 1961 press release on Prince Edward. In response to Attorney General Kennedy’s attempt to stop state funding being used for tuition assistance for White students to attend segregationists academies Byrd uses this moment to praise Prince Edward as a “gallant” county “fighting against great odds to protect a principle it believes to be right.” He continues by portraying Prince Edward, and Virginia, as victims, citing that Kennedy’s proposal was an “attempt to punish an entire State because the action of one county displease the U.S. Attorney General.”

Harry Flood Byrd’s press release regarding the “intervention by the Attorney General of the United States in the Prince Edward County School District” (MSS 9700, Papers of Harry Flood Byrd. Images by U.Va. Library Digitization Services)

While Byrd holds Prince Edward up as a model community for its demonstration, he simultaneously paints the entire Commonwealth as a victim at the hands of an intrusive federal government. Byrd’s press release continues with a somewhat ironic warning against bitterness in what he sees as being a struggle for unity: “Such action will sow the seeds of intense bitterness throughout Virginia and the South when unity is needed as rarely before.” This document, like many of Byrd’s speeches, press releases, and correspondence, serves as a means for helping us to understand both the history and discourse of Massive Resistance. The language was as much about maintaining state’s rights as it was demonstrating the resilience needed to protect the South’s way of life at all costs.

When I’m asked why I devote research to a moment in our nation’s history that is so painful and ugly my response is simple: We must understand how race has operated historically through language and having access to archival sources is paramount to this. If we understand how racist discourse has functioned and if we continue to trace how it morphs, we can better prepare ourselves to dismantle and challenge the discourse of race. Archives, especially those with strong digital components and support, can aid us in our quest to dissect words and movements over long distances so that our struggle doesn’t have to be limited by travel funding or leaving campus on a research sojourn across the country.

Detail from the closing page of an anti-integration pamphlet also used by Professor Epps-Robertson in her research. (Broadside 747. Image by U.Va. Libraries Digitization Services)