Our latest exhibition, Sacred Spaces: The Home and Poetry of Anne Spencer, offers a glimpse into the exquisite world of Civil Rights activist, librarian, gardener, and poet Anne Spencer (1882–1975). Spencer spent over fifty years turning her house and her garden into a more beautiful and gentle world than the one outside her gates.

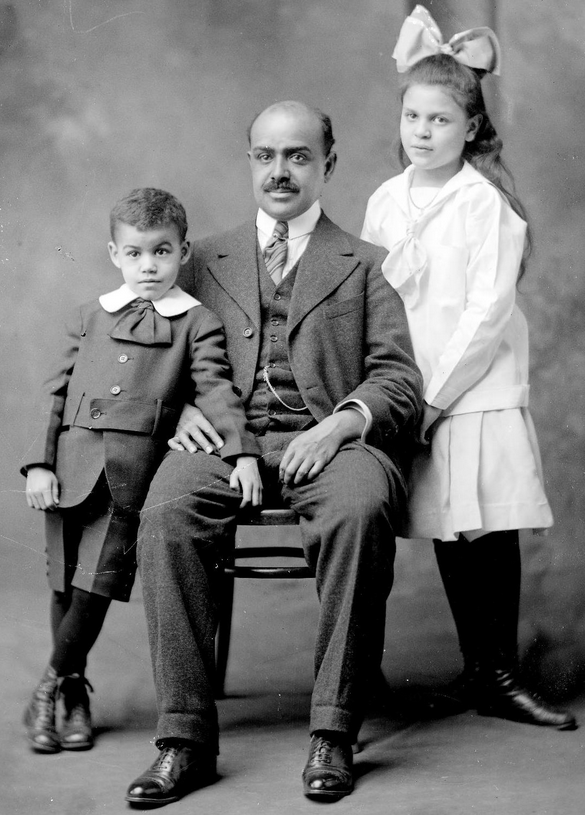

Inspired by the photographs taken by noted architectural and landscape photographer John Hall, the exhibition explores how each space was sacred in its own unique way. In “Any Wife to Any Husband, A Derived Poem,” Spencer writes, “This small garden is half my world.” With a myriad of flowers, a lily pool, and a cottage study, Anne’s garden was her own private poetic Eden. At the same time, her house, the other half of her world, was a welcome refuge for African Americans who would have been prevented from finding lodging in Lynchburg because of the color of their skin. The Spencers hosted civil rights activists, writers, and other famous African Americans such as Gwendolyn Brooks, George Washington Carver, Countee Cullen, W.E.B. DuBois, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Thurgood Marshall, and even Martin Luther King Jr.

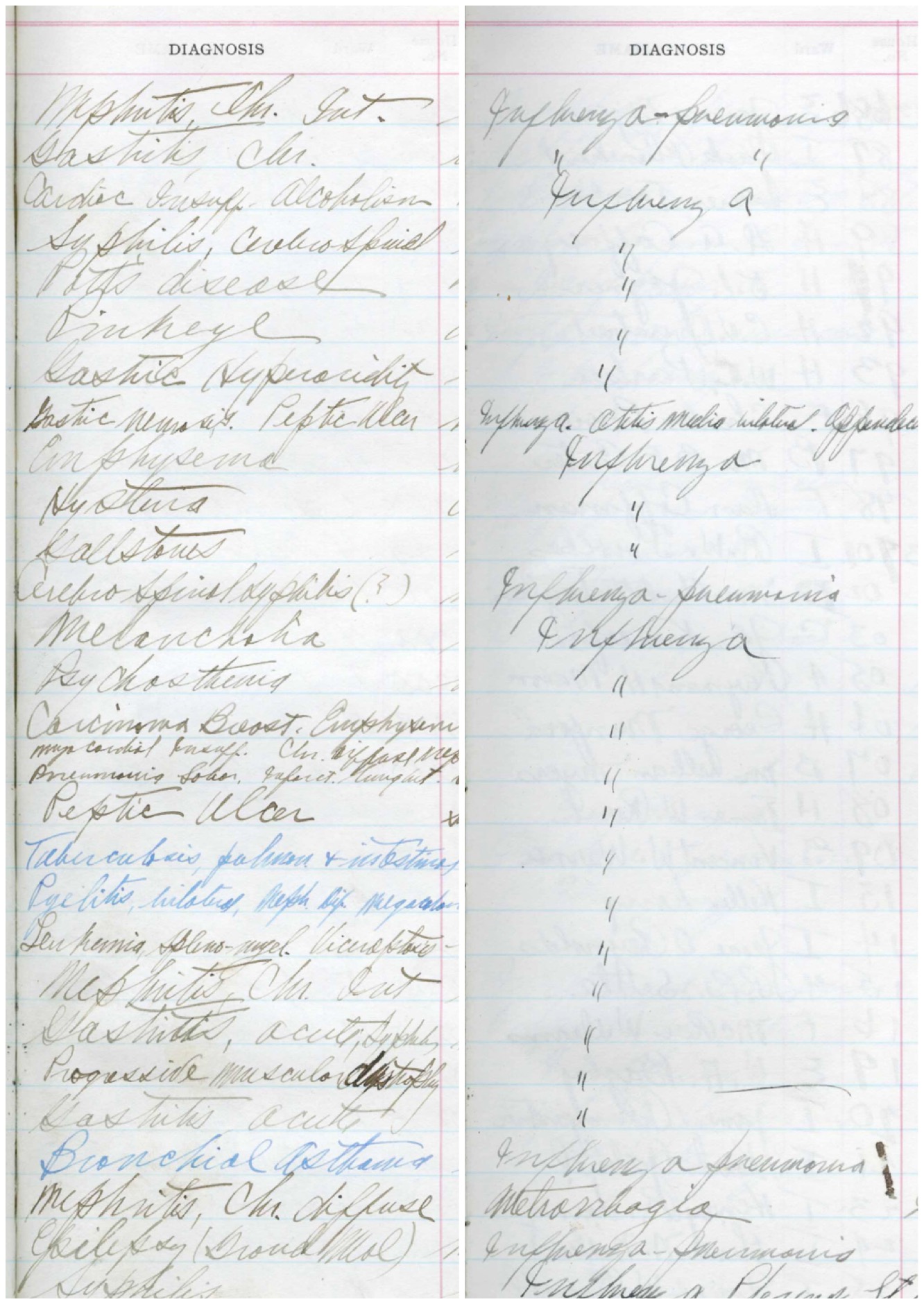

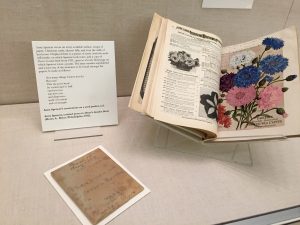

However, for Spencer, poetic creation and political activism were not separated by the boundaries of architecture. Rather, they were wreathed together by Spencer’s own hand in the house and in the garden. She wrote about politics on seed packets and gardening catalogues in her garden cottage, but at the same time, a poem she wrote about her favorite flower, “Lines to a Nasturtium (A Lover Muses)” is, to this day, painted on the kitchen wall.

Shown here is a packet of seeds that Spencer used to take notes and a copy of Dreer’s Garden Book , open to an unpublished poem

The exhibition is broken down into three parts—house, garden, and garden cottage (known as “Edankraal”)— in order to show how politics and poetry, public and private, the past and the present converge in the sacred spaces Anne Spencer created. To compliment John Hall’s stunning photographs of the house and garden, we have tried to fashion each of Spencer’s sacred spaces through the physical artifacts—manuscripts, books, letters, gardening paraphernalia— she left behind.

“Sacred Spaces” is on view through January 27, 2017 in the first floor gallery of the Harrison Small building. Spencer’s home is open to the public today as the Anne Spencer House and Garden Museum. For more information, see annespencermuseum.com. To learn more about John M. Hall’s photography, please visit www.johnmhallphotographs.com.