This week, we are pleased to feature a guest post by Ethan King, one-time Special Collections graduate student assistant, who is now pursuing his Ph.D. in English at Boston University. Ethan takes a strong interest in Faulkner, and has generously written for us about Faulkner’s fascinating later-life work as a cultural ambassador, a subject featured in our current exhibition, Faulkner: Life and Works.

In the last of his four U.S. State Department-sanctioned missions as a cultural ambassador, William Faulkner ventured abroad to Venezuela in the spring of 1961, completing a busy itinerary rife with press conferences, public discussions, and cocktail parties designed to, as Hugh Jencks explains in his “Report to the North American Association on the visit of Mr. Faulkner,” “strengthen and improve relations between the people of the two countries” (MSS 15242). The materials regarding Faulkner’s visit to Venezuela, written and compiled by members of the North American Association (N.A.A)., esteemed Venezuelans, Americans living in Venezuela, and Faulkner himself, are housed in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. They form a compelling time capsule, containing evidence of the diverging geopolitical visions of Faulkner and the State Department during the Cold War, as well as Faulkner’s eminence as a global writer and figure.

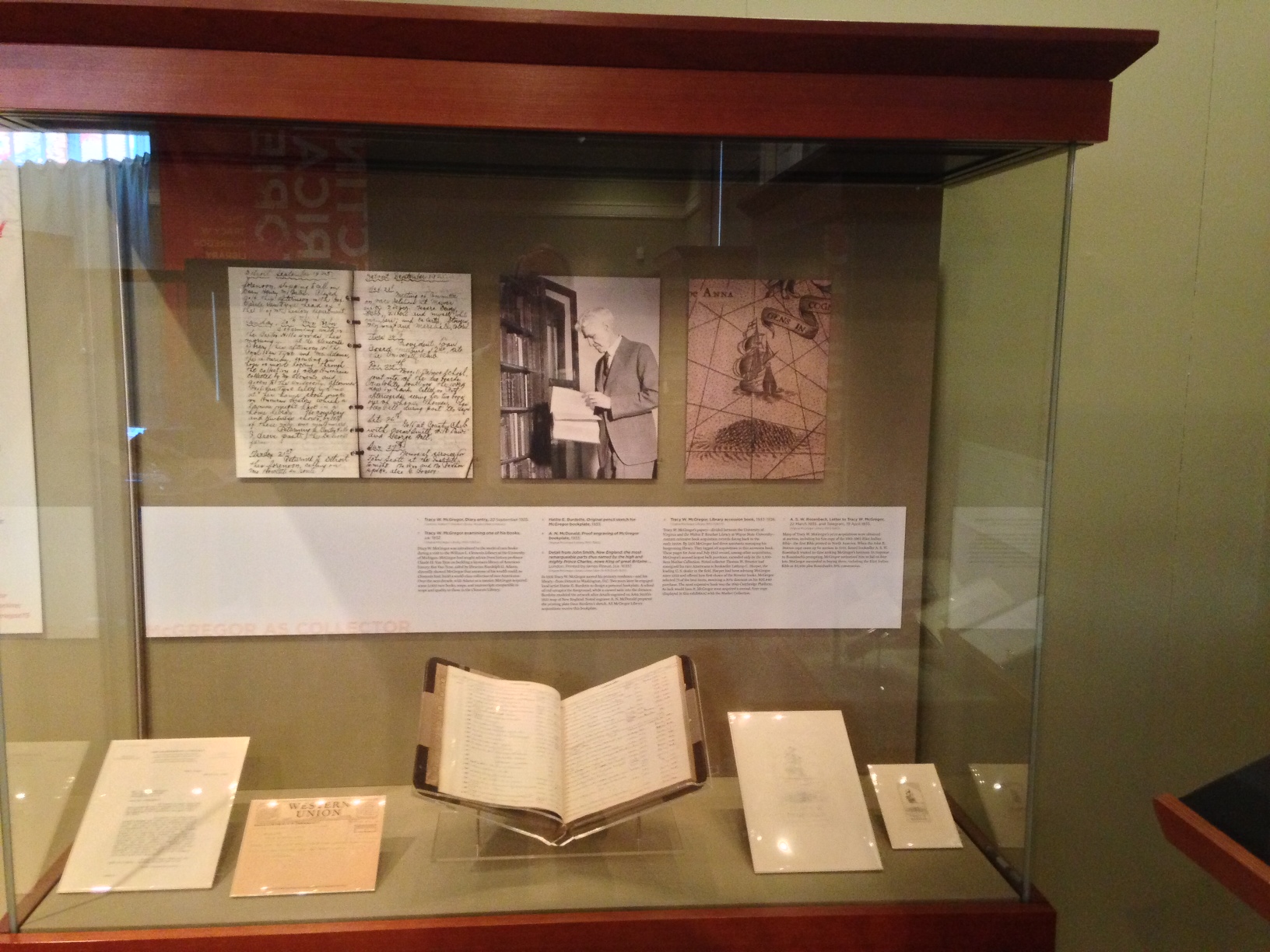

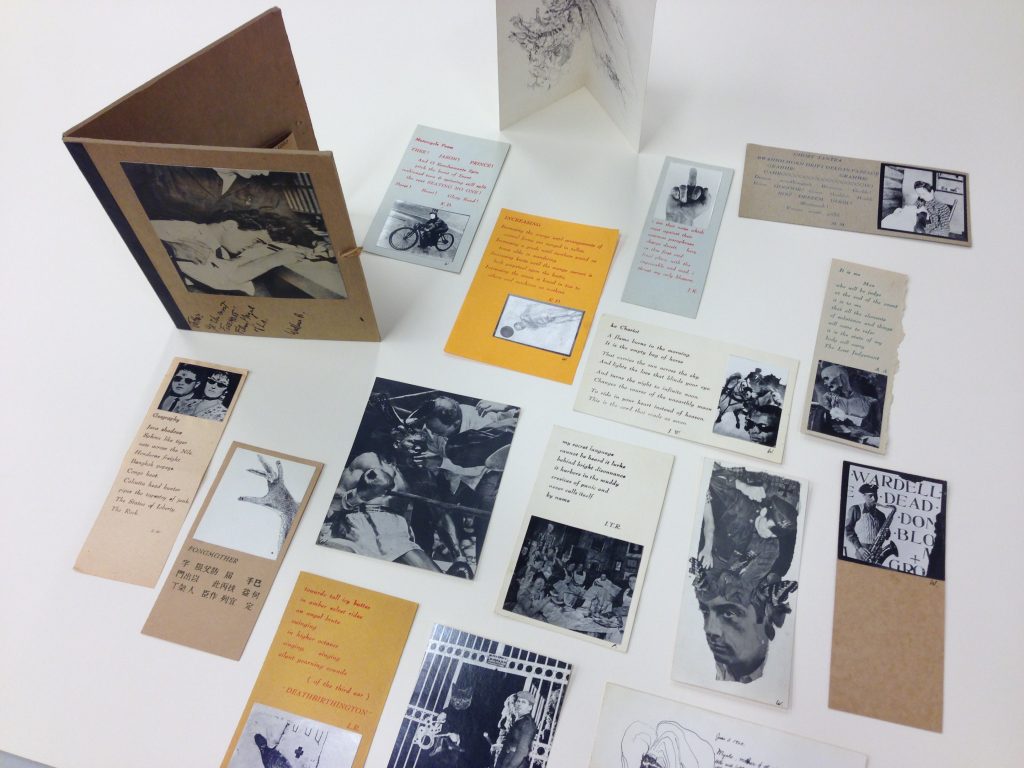

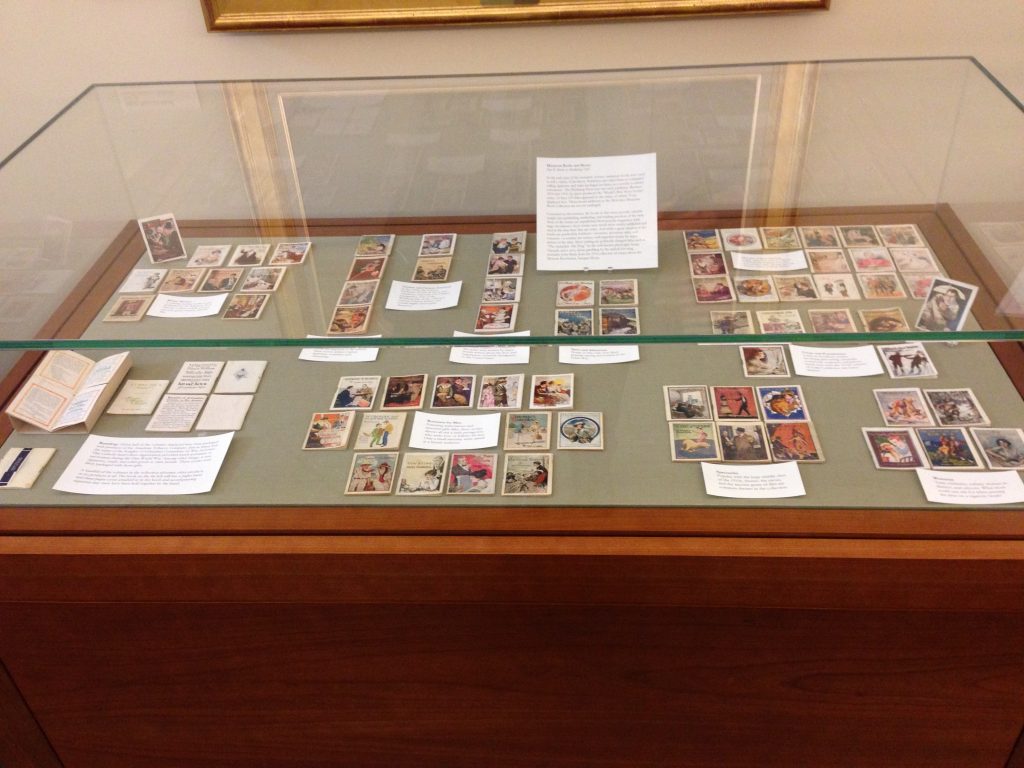

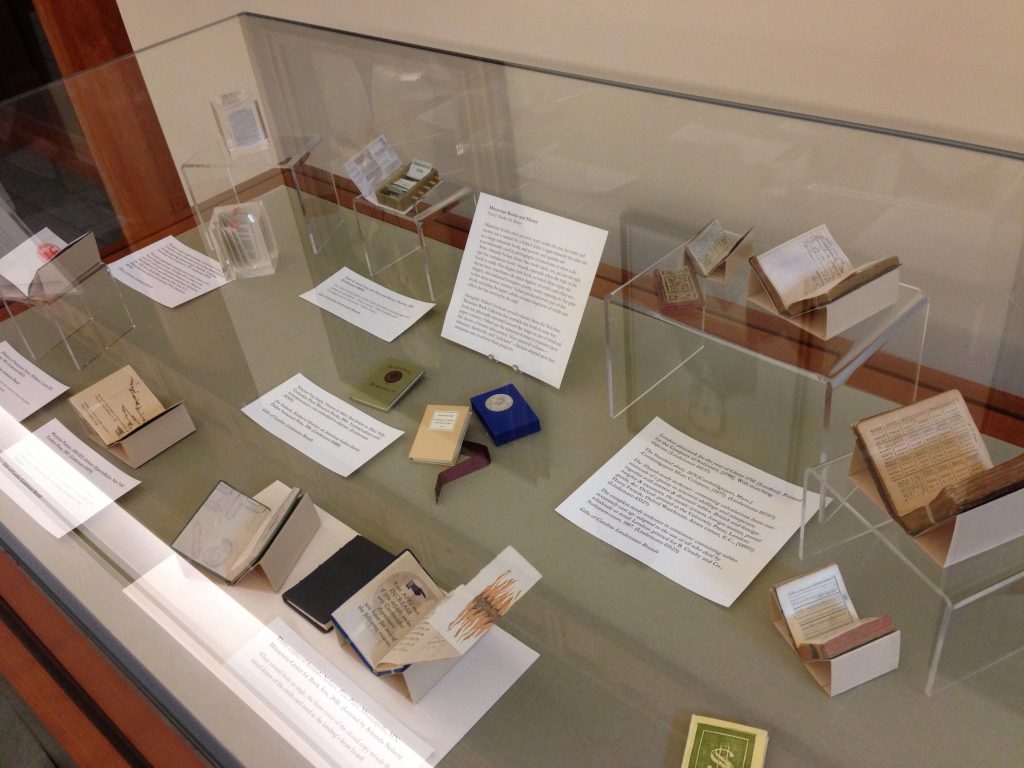

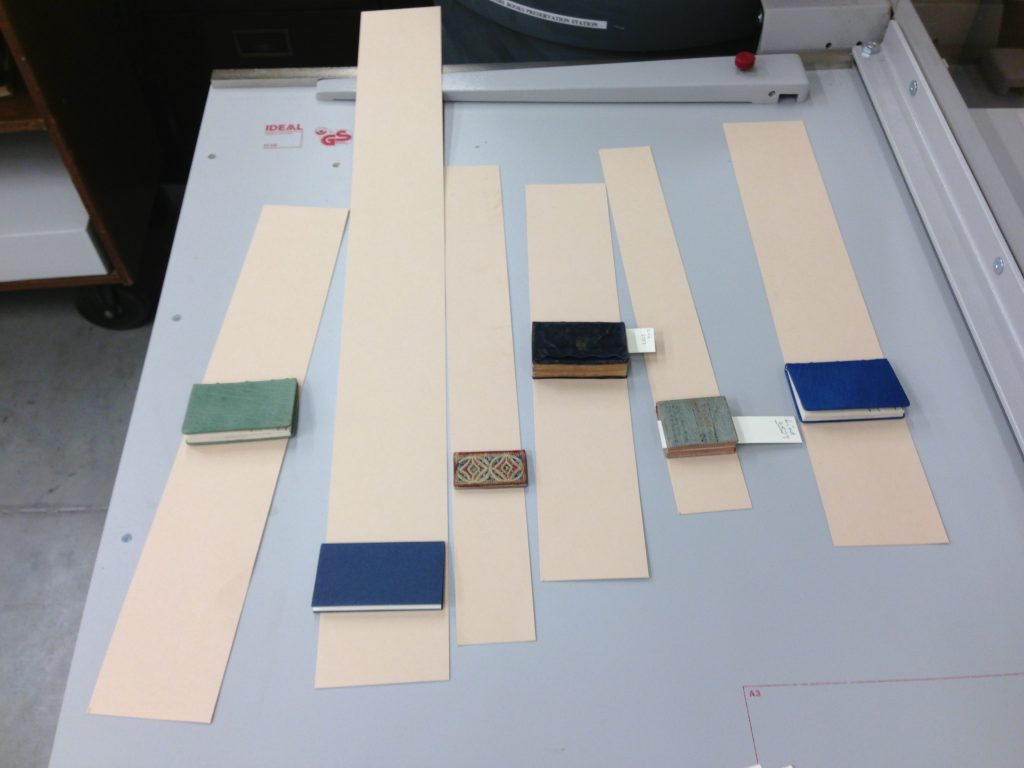

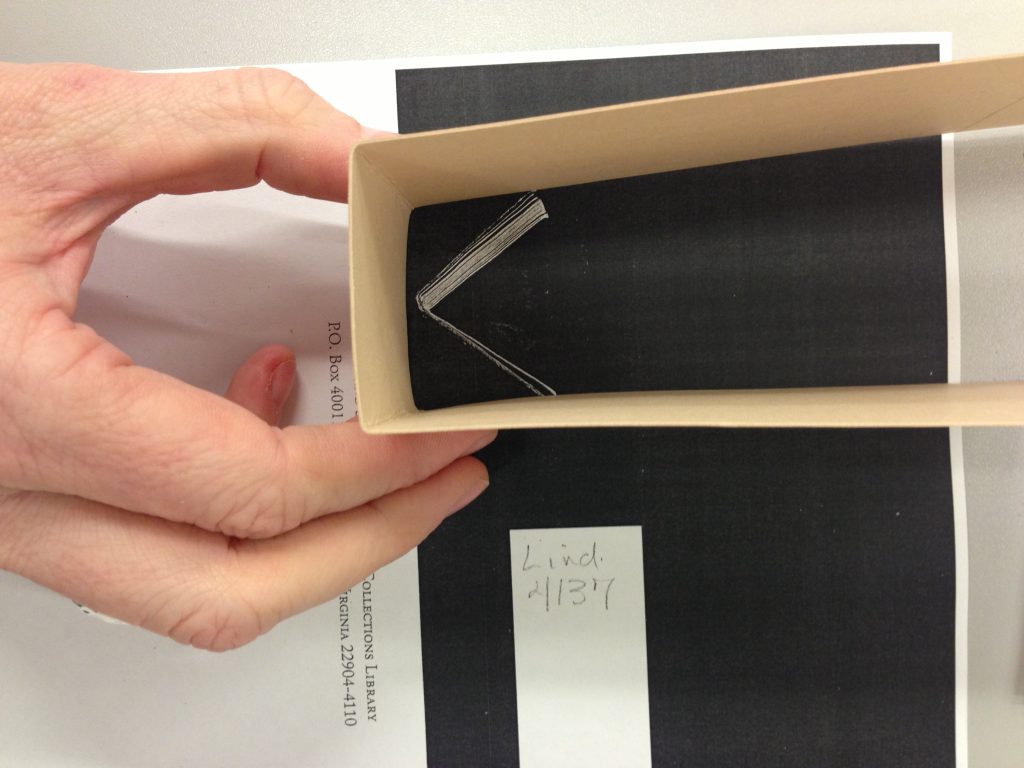

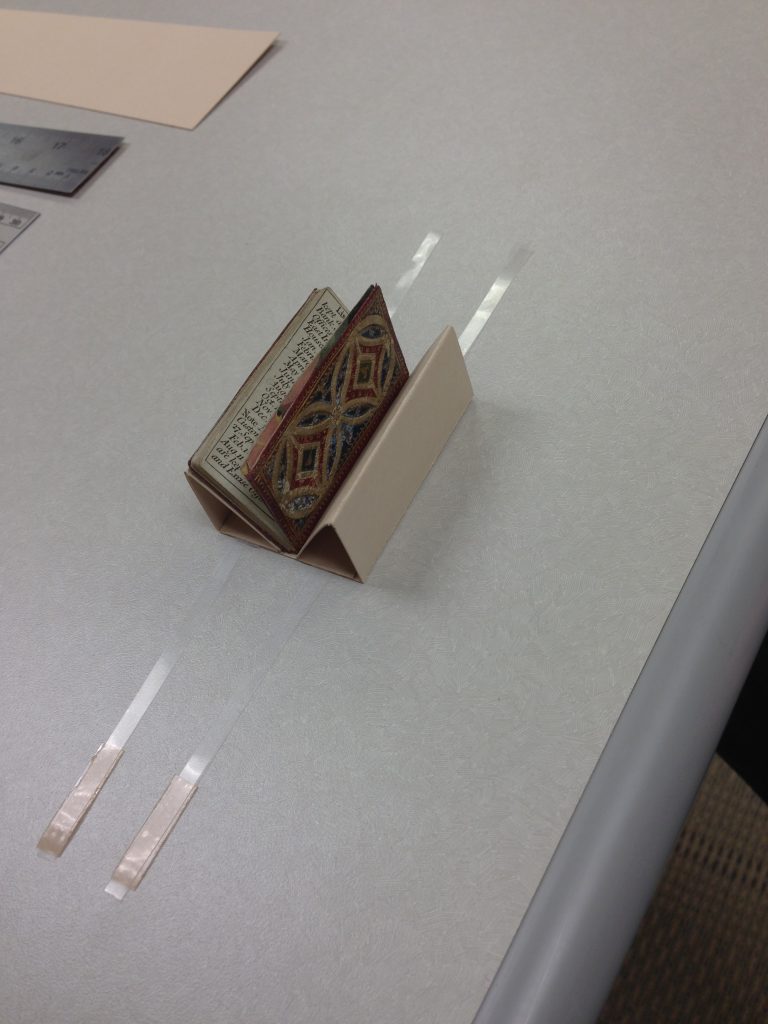

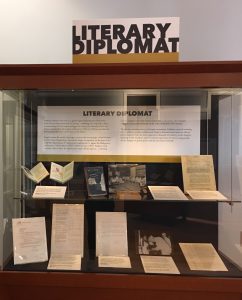

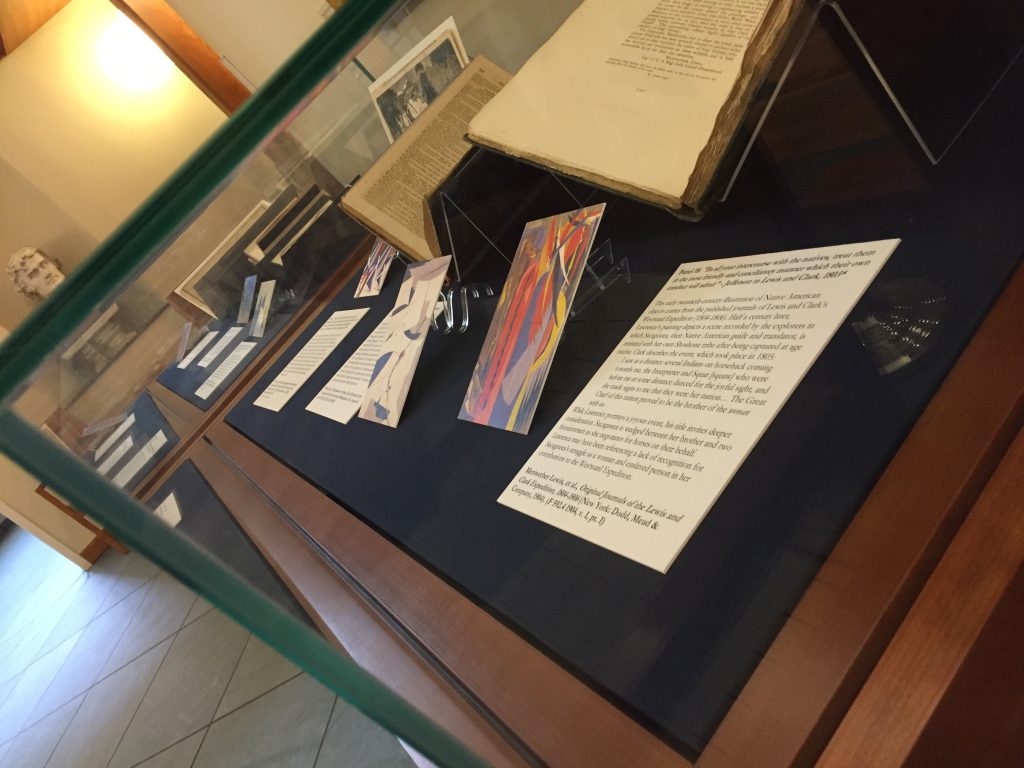

A case from our exhibition with documentation of Faulkner’s trips across the Globe, including his heavily stamped passports, photographs of encounters with citizens of various nations, and official U.S. government reports on his activities.

Having already traveled under similar governmental auspices to Brazil in 1954, Japan in 1955, and Greece in 1957, Faulkner accepted the invitation to Venezuela reluctantly, citing his growing frustration with political gerrymandering, and perhaps feeling the potential inefficacy of such a trip:

Please excuse this delay in answering the letter of invitation from the North American Union of Venezuela [sic]. I had hoped that the new administration by that time would have produced a foreign policy. Then amateurs like me (reluctant ones) would not need to be rushed to the front.

Although much of the correspondence leading up to Faulkner’s departure in March of 1961 bespeaks his discomfort with the foreign policy of the State Department, it also suggests his respectful acquiescence to the duty he had been prescribed. On the one hand, he declares to his mistress Joan Williams in a dynamic letter from January 1961,

the State Dept is sending me to Venezuela, unless by that time the new administration will have created an actual foreign policy, so that they wont need to make these frantic desperate cries for help to amateurs like me who dont want to go, to go to places like Iceland and Japan and Venezuela to try to save what scraps we can.(MSS 15314)

On the other, he writes to Muna Lee, the Office of Public Affairs adviser in Washington and the key mediator between Faulkner and the N.A.A.,

please pass the word on that I dont consider this a pleasure trip, during which Faulkner is to be tenderly shielded from tiredness and boredom and annoyance. That F. considers it a job, during which he will do his best to serve all ends which the N.A.A. aim or hope that his visit will do.” (MSS 7258-f)

The formal occasion for Faulkner’s trip was the Sesquicentennial of Venezuelan Independence, and the North American Association had been assisted in its preparations by three of Venezuela’s leading writers: Rómulo Gallegos, Arturo Uslar Pietri, and Arturo Croce. In addition to meeting these writers, Faulkner spoke at length with the President of Venezuela, Rómulo Betancourt, at an official luncheon. Not succumbing to a harrying schedule, Faulkner made sure he was available to all who wanted to speak with him, and as Joseph Blotner declares in his biography of the author, “his efforts did not go unappreciated by a group of journalists who had called him ‘el hombre simpático.’ […] Some of the reporters began calling him simply ‘El Premio,’” for being a recipient of the Nobel Prize” (688). While local papers covered Faulkner’s visit in great detail, Venezuelan radio and television coverage of his visit were orchestrated by the U.S. Information Service: they produced a film documenting his visit and delivered several news bulletins to eight radio stations, keeping the listening audience informed at all times of Faulkner’s whereabouts and activities. That the local media did not produce these radio and television broadcasts might suggest that the N.A.A. saw the trip as an opportunity not solely to “strengthen and improve the relations between the people of the two countries,” but to extend U.S. political and artistic supremacy in Latin America.

The official report written by Hugh Jencks for the N.A.A. situates Faulkner’s trip in the cultural context of the Cold War:

The cultural leaders of Venezuela, many of whom are pre-disposed to take an anti-U.S. attitude on all international issues, include writers, artists, newspaper commentators (particularly those connected with El Nacional), educators and people in government. The group also includes many on-the-fencers. Its members tend to agree with the Communist tenet that the United States is grossly materialistic, with no cultural achievements. To bring a literary figure of the stature of Faulkner to Venezuela was an effective refutation of this view. (MSS 15242)

Jencks goes on to write, “The leftist extremists, who certainly would have exploited the visit for anti-U.S. attacks if they felt they could have made hay, remained silent. Mr. Faulkner’s evident popularity was too great for them to make the pitch” (MSS 15242). Commenting on and exaggerating Faulkner’s popularity amongst the Venezuelans, Charles Harner declares in his report “Evidence of Effectiveness, Faulkner vs. Astronaut” that “As far as PANORAMA, the leading daily newspaper of Maracaibo, is concerned, William Faulkner’s visit to the second largest city of Venezuela was more important than Russia’s success in launching a man into space” (MSS 15242). Harner’s declaration springs from the fact that the newspaper granted Faulkner and Russian astronaut Yuri Gagarin equal print space, allotting Faulkner the portion above the fold. With passages such as these, one cannot help but read the U.S. official reports of his trip as containing calculated embellishment and sanctimonious self-congratulation and as espousing American exceptionalism rather than a genuine interest in cultural interchange.

Faulkner, in contrast to U.S. officials, made bona fide attempts to generate cultural exchange during his trip, cherishing his discussions with university students over the highbrow cocktail parties with political elites; delivering his acceptance speech for the Order of Andrés Bello, the country’s highest civilian decoration, in Spanish (a language he was only starting to learn); expressing an earnest desire to experience all Venezuelan food and in his words, “saborear el vino del país.” Further, he refused housing with Americans living in Venezuela, indicating that he did not want the trip to be a “shabby excuse for two deadhead weeks with [his] North American kinfolks and their circle.” He reserved his autograph signing for locals: he writes to Muna Lee before the trip,

If possible, I would prefer to avoid being asked for autographs by Anglo-Americans, since the addition of my signature to a book is a part of my daily bread. I intend, and want, to sign any and all from Venezuelans and other Latin Americans who ask. (MSS 7258-f)

Faulkner’s attentiveness to the tenets of his trip (i.e. exercising a willingness for dialectical, rather than unidirectional, cultural construction) rewarded him upon his return to Virginia with, among other things, Spanish copies of the works of Armas Alfredo Alfonzo and Rómulo Gallegos, sent and inscribed by both authors.

Perhaps most importantly, after being profoundly touched by seeing his works printed in translation and by interacting with a foreign readership knowledgeable of and influenced by his work, Faulkner felt it necessary to use his literary status to implement a program through which Latin American books could be translated into English and published in the United States. In this way, Faulkner’s trip to Venezuela planted the seeds of what would become the William Faulkner Foundation’s Ibero-American Novel Project, a Project that, as Helen Oakley explains in her essay “William Faulkner and the Cold War: The Politics of Cultural Marketing,” “played a vital ideological role in the unfolding drama of Faulkner’s relationship with Latin America.” The Foundation’s statement regarding the project is as follows:

Many novels of the highest literary quality written by Latin-American authors in their native languages are failing to reach appreciative readers in English-speaking North America; and accordingly the William Faulkner Foundation, at the suggestion of William Faulkner himself, is undertaking a modest corrective program in the hope of contributing to a better cultural exchange between the two Americas, with an attendant improvement in human relations and understanding. (MSS 10677)

However, as Faulkner died soon into the Project’s infancy, the Project ran into a host of challenges and difficulties created by the market forces of the United States. In my next post, I will cover in more detail the Ibero-Novel Project, as well as the political and cultural struggles that led ultimately to its failure.

Keep your eyes peeled for Part II, coming soon!

![Joseph Hutchings purchased 8 volumes of of Shakespeare "for [his] self" (MSS 467).](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/theobalds_shakespeare.jpg)