William Faulkner adopted various personae throughout his life—poet, father, Mississippi gentleman, Nobel Prize winner— but the persona that required his ability to invent and create the most was William Faulkner, Englishman. Most of Faulkner’s childhood was spent making flying contraptions with his brothers and taking turns being the flight-test dummy. He never gave up on his dream of flying. Years later, when World War I broke out, Faulkner saw his opportunity to get into a plane and to get into the air. Worried about his size, Faulkner stuffed himself full of bananas and water before going to Air Force recruiting station. Despite his preparations, he was rejected for being under regulation height and weight. After this rejection, Faulkner went with his childhood friend and mentor, Phil Stone, to Yale for several weeks. While at Yale, Faulkner was persuaded by some of Stone’s friends to try the Canadian RAF rather than wait for the draft. To join the RAF, however, they had to be British subjects.

Faulkner and Stone went to work. They practiced English pronunciation. They forged documents. They invented a fictional vicar, the Reverend Mr. Edward Twimberly-Thorndyke, and wrote letters of reference from him on their behalf. They even enlisted the sister of Phil Stone’s British tutor at Yale as a “mail drop.” When he presented himself at the RAF recruiting station, his name was William Faulkner—not Falkner— and he claimed that he was born in Finchley, UK, and that his mother had emigrated to Oxford, Mississippi years before. Despite his height—five foot five and half inches— and his weight, he was accepted as an applicant for pilot training.

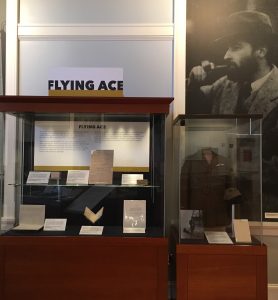

Though Faulkner’s time in the RAF was limited to 179 days in Canada, (and it is debatable whether he even flew a plane during his training), Faulkner dressed as a conquering war hero when he returned to Oxford after the war. He purchased an officer’s uniform right before his discharge, which he wore, and posed for photographs in, all over town even though it was against regulation to wear a uniform after being discharged. (He was belatedly promoted to Honorary Second Lieutenant in March 1920). Since he was already dressed for the part, he invented tall tales about flying and seeing combat too.

His most often-told tale was that he crashed a plane during training, which resulted in either a fictitious silver plate in his head, or a fictitious leg injury that made him walk with a limp. Faulkner told this tale for decades. Even some of his own family members believed his story of the plane crash, though they knew he had not seen combat. It was not until 1950 that Faulkner admitted in a letter to Dayton Kohler that he had not seen combat and had not been injured in a plane crash.

Faulkner eventually did learn how to fly, however, and did so recreationally for the rest of his life, even after the death of his brother, Dean, in a plane crash in 1935. In addition to the tall tales he made up, his own experiences in the air inspired a number of Faulkner’s works. His first published short story, “Landing in Luck” and his novels, Soldier’s Pay and Pylon, are a testament to his love of flight.

For a chance to see Faulkner’s RAF uniform and the letter correcting his tall tales in person, come see “Faulkner: Life & Works,” on view at the Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library from February 6, 2017 to July 7, 2017.