This week, we are pleased to feature a guest post from researcher Charles Morrill. Mr. Morrill is an independent scholar researching the creation of Thomas Jefferson’s polygraph by Charles Willson Peale and John Isaac Hawkins. He is also a guide at Jefferson’s home, Monticello.

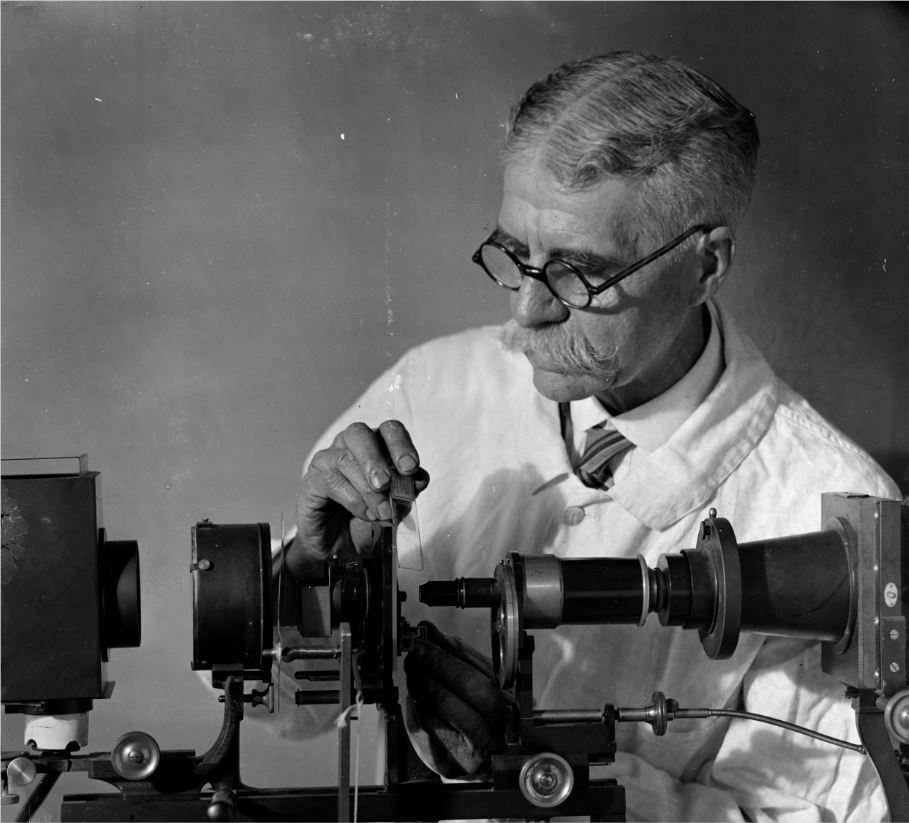

Contemporaries called Arthur J. Weed the “shop man” of the University of Virginia physics department, but he was much more. True, he was a machinist, a woodworker, and also a photographer, but he was even more than those things as well.

He was a scientific-instrument maker from upstate New York who often lived in the basement of Rouss Hall, the building that housed the university physics department in the years between the great wars of the last century. He could make, machine, or build just about anything. For years he quietly worked to advance physics; medicine; and frequently on his own time, and with his own money, the science of detecting earthquakes.

He came up with a type of strong motion seismograph used by the U.S. government for many years, and machined the precise parts that allowed U.Va.’s physics department to do important work in the 1930s.

The students called him “old Weed,” but never to his face. He came to U.Va. around 1920, a slender, middle-aged man who sported a “Mr. Chips” head of white hair and round glasses that probably made him look Edwardian by the standards of the Jazz age.

He didn’t seem to mind.

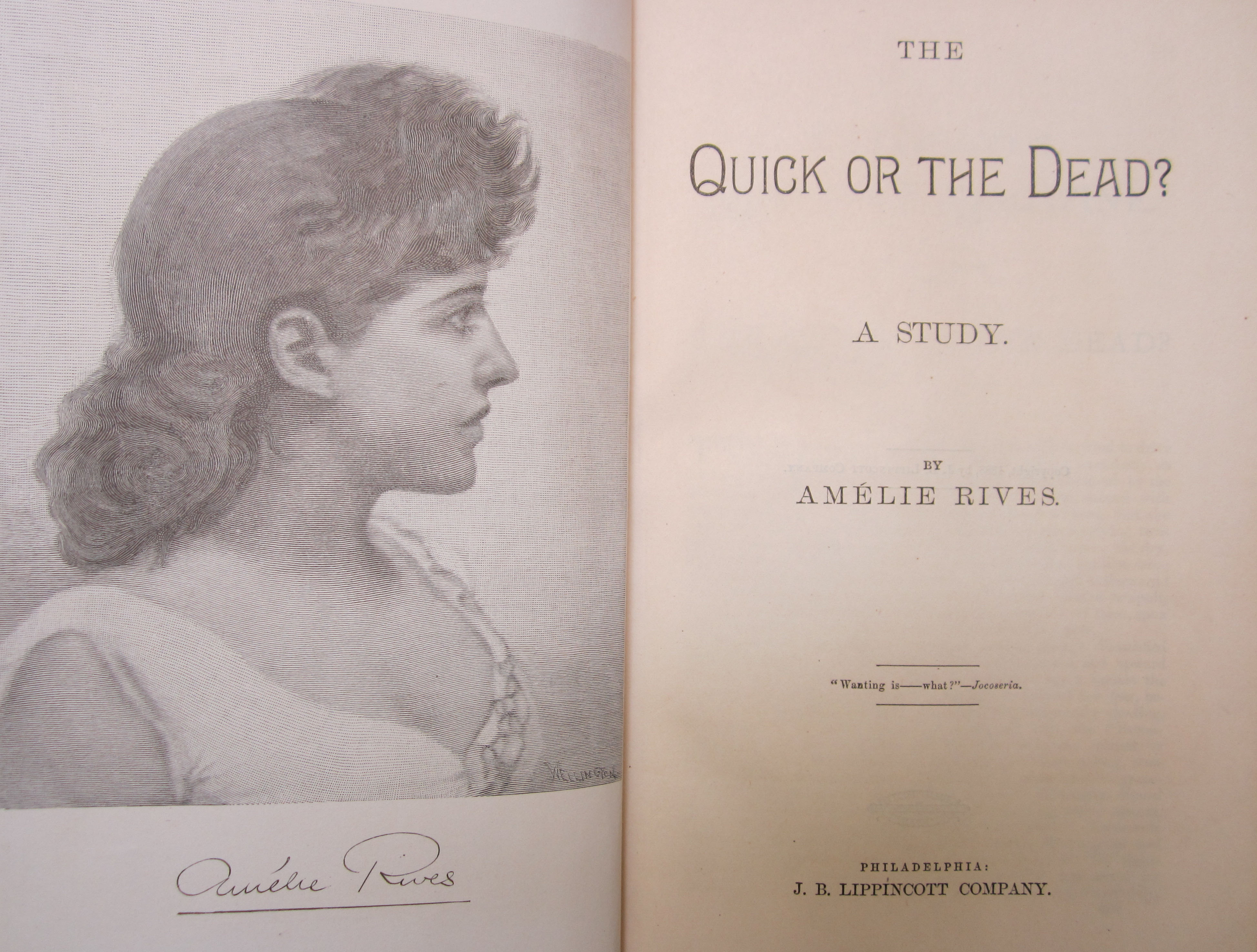

Arthur J. Weed at work.(MSS 12558. Digital image from glass plate negative, by University of Virginia Digitization Services.)

In fact, Weed seems to have been as amused by the students as they were of him. He once told Professor Frederick Lyons Brown that students used to measure the acceleration of gravity by dropping a brick down an open stairwell at Rouss Hall and timing it with a stopwatch.

“But,” said Weed. “This practice was discontinued when one boy became flustered and dropped the watch and tried to time it with a brick.”

He loved photography and cats. He worked for the university hospital too, taking high-quality microscopic images so students could learn the processes of disease.

And he loved the university itself, constantly photographing its buildings, sporting events, and graduations. He seems to have stuck with glass-plate negatives for most of his life. Special Collections has nearly two hundred photographs taken by Weed, nearly a hundred on extremely fragile thin glass plates: cats, the lawn, his wife Emma, more cats, vacations, and always another shot of the Rotunda in the spring, in the summer, in the fall, and in the winter.

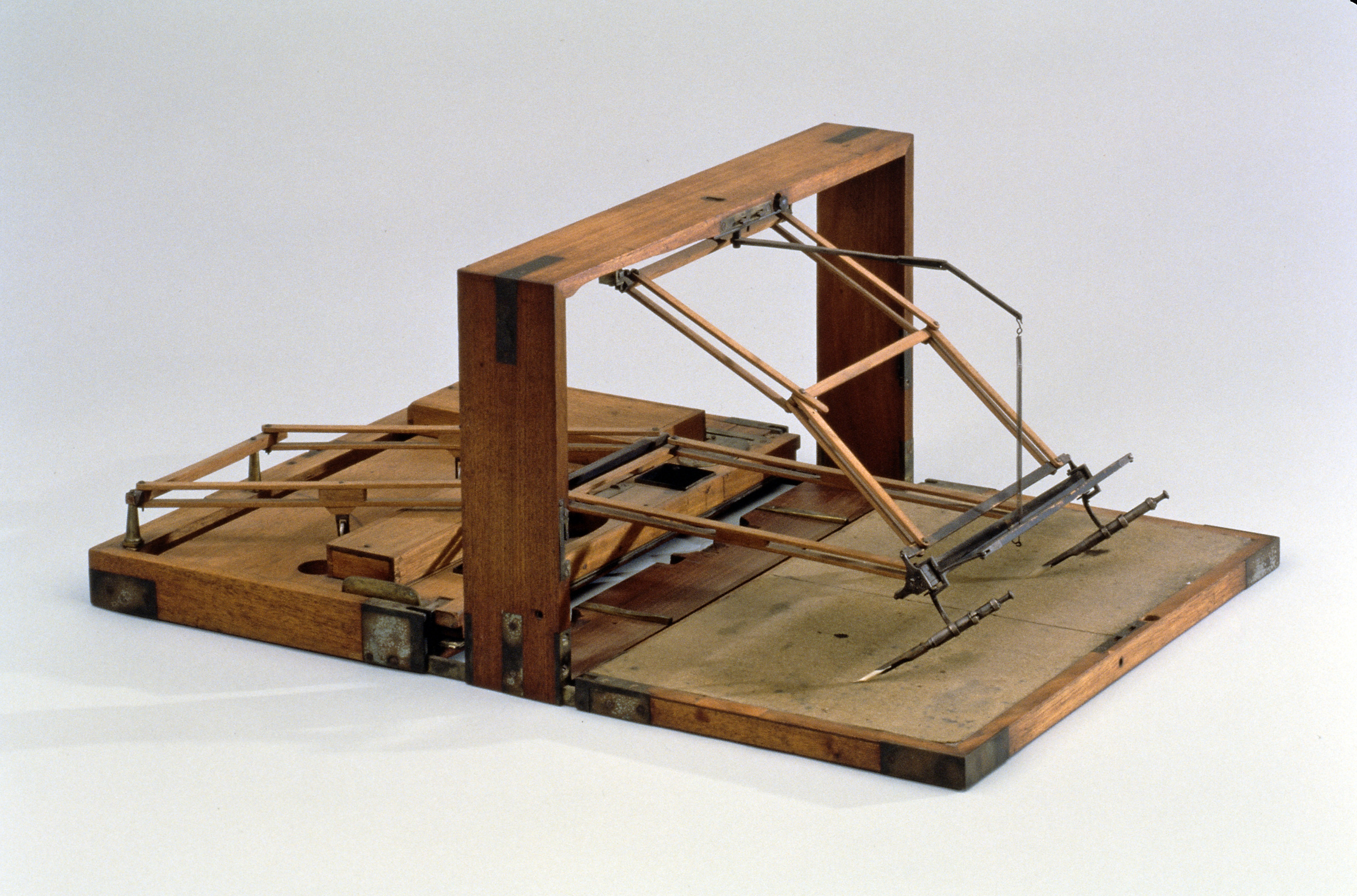

He captured Monticello in its first few years as a public museum before much restoration. Weed did his part for that effort too. That’s how I found out about him. In 1922, he restored Jefferson’s polygraph, or copy machine, for U.Va.

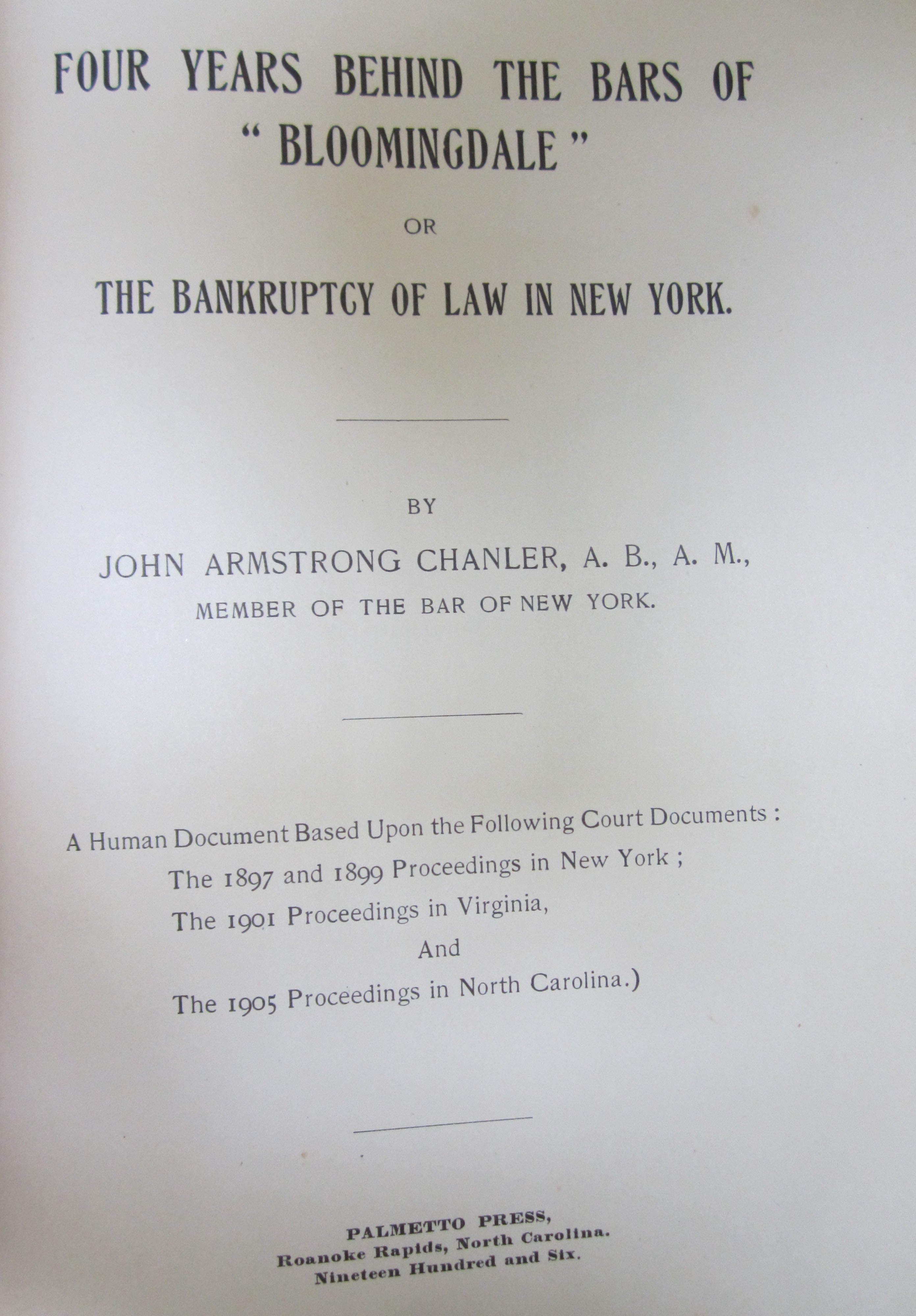

The University of Virginia’s polygraph as it looks today, almost a century after Weed’s restoration work. The polygraph is on long-term loan to Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and is seen by nearly a half-million visitors yearly on the house tour. (Image courtesy of Monticello.)

“The polygraph has just been restored to a working condition in the workshop of the Rouss Physical Laboratory at the University of Virginia by the mechanical A. J. Weed,” the Washington Post reported on May 28, 1922.

UVA subsequently loaned the machine to Monticello in 1947. It remains on view for visitors in Jefferson’s “cabinet” or study.

Weed lived in more humble surroundings, and stuck to a simple bed in the basement of Rouss Hall. He apparently commuted home to Washington D.C. on weekends until the early 1930s when he and his wife Emma bought a house on 17th Street in Charlottesville.

And it was in the depths of Rouss Hall that Weed worked to perfect his great love: the strong-motion seismograph.

Though seismographs had been around for decades in Weed’s time, instrument makers tended to make them ever more sensitive. Trouble was, if an earthquake actually took place next to such a device it could not record anything meaningful. At the suggestion of an engineer he’d heard at a lecture, Weed worked at devising instruments tuned to “hear” and record strong vibrations on the theory that they might be of use to those who designed bridges and buildings in earthquake zones.

He was, of course, absolutely right.

“Mr. Weed has designed an instrument easily portable and capable of making an accurate record of stresses and strains in a building shaken by a quake,” the Associated Press reported on May 4, 1932. “It is set with a hair trigger that releases with the first tremor. For the next two minutes a record of the quake intensity is traced upon a smoked glass plate.”

Weed also worked on his own larger more sensitive seismographs, some taller than an adult person, wonderful pieces of machine work and theory, one bedded deep in the ground beneath Rouss Hall.

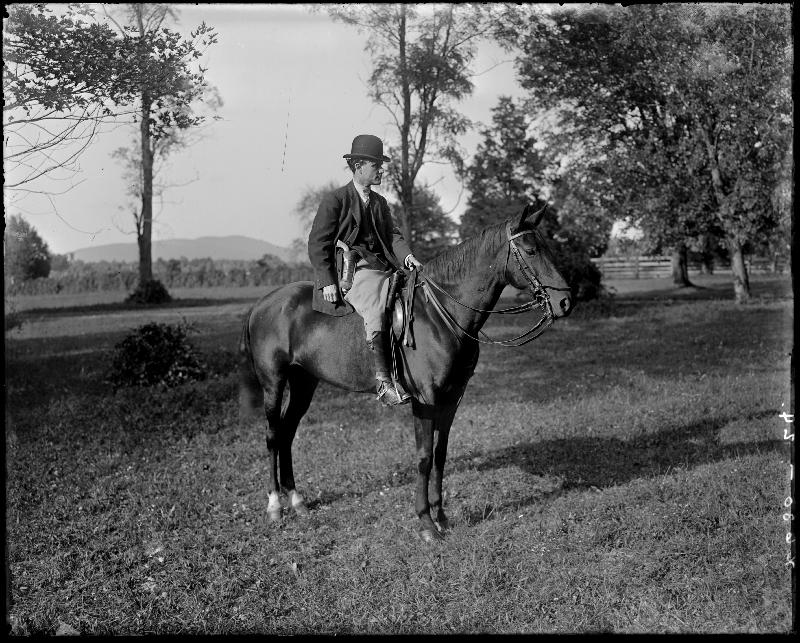

Weed and one of his seismographs, undated. (MSS 12558. Digital image from glass plate negative, by University of Virginia Digitization Services.)

The early 1930s saw Weed working with U.Va. Physics Professor Jesse Beams to develop the ultracentrifuge described by both in Science magazine (June 10, 1931). Looking like some gleaming child’s top on steroids, the instrument ultimately spun a half-million revolutions per minute. Years later Beams took the idea to the Manhattan Project during World War II as one method for separating different types of uranium.

Both Beams and Weed posed for photos with their device in the 1930s. One, the intent young professor, the other his machinist and something more.

On April 15, 1936, Weed gave a lecture titled “Some Experiments With Soft Cast Iron Magnets” at the University’s Physics Journal Club in Rouss Hall, where he’d spent some of the best years of his life.

He finished speaking, collapsed, and died of apparent heart failure.

The University buried him in a lovely quiet spot at the northeast corner of its cemetery. Emma moved back home to upstate New York but lies in Charlottesville next to Arthur today. No one got around to engraving the date of her death on their headstone.

By the 1960s the U.S. government had phased out most Weed strong-motion seismographs in California. One or two may remain in museums.

Someone once said we stand on the shoulders of giants and I think that’s true. But, I also think it’s true that we stand on the shoulders of quiet photographers and cat-loving machinists with a passion to build and to help.