This week we are pleased to feature a guest post from U.Va. English Department doctoral candidate Ann Mazur. Ann contacted us earlier this year with a purchase request and we happily obliged. Here, she tells us how this purchase has contributed to her dissertation. Thanks, Ann!

As a Ph.D. student in English literature, I am currently completing my dissertation, The Nineteenth-Century Home Theatre: Women and Material Space. My project aims to recover the nineteenth-century parlour play, an important dramatic outlet to Victorian middle-class women. The parlour play, or home theatrical, was a dramatic performance staged most often within the home, though sometimes plays were also performed at schools or at other venues to raise funds for charities. As the nineteenth century progressed, home theatricals largely replaced earlier forms of home entertainment such as tableaux vivants (“moving pictures”) and charades. Most theatricals lasted around fifteen to thirty minutes, though occasionally they are lengthier.

I argue that in the years from 1860 to1900, the parlour play became more popular among the middle-classes and was especially significant for women. Other literary scholars have shown that women who wrote for the public stage faced immense obstacles and prejudice. Likewise, Victorian public stage actresses had to battle an association with prostitutes. In contrast, the parlour play permitted women to both write and act freely.

One of the difficulties of my project—though this has simultaneously made it more exciting—is tracking down the ephemeral parlour play. Home theatricals were often printed in book collections of plays and in fragile pamphlets. Many libraries have not thought to save this popular entertainment, and I’ve often had to turn to the tireless services of Interlibrary Loan to find plays on microfilm, microcards, and less often, in the form of the real physical pamphlet or book. I have found some items only in the listings of rare booksellers, and as a result have built my own personal collection of parlour plays. In searching AbeBooks.com, I made an exciting find: a set of three letters written by mid-century parlour playwright Eliza Keating to her publisher T. H. Lacy, concerning the publication of her Acting Charades. All evidence in my research pointed to women having an easier time writing for home theatre, but here was a woman’s actual voice offering real details about this process.

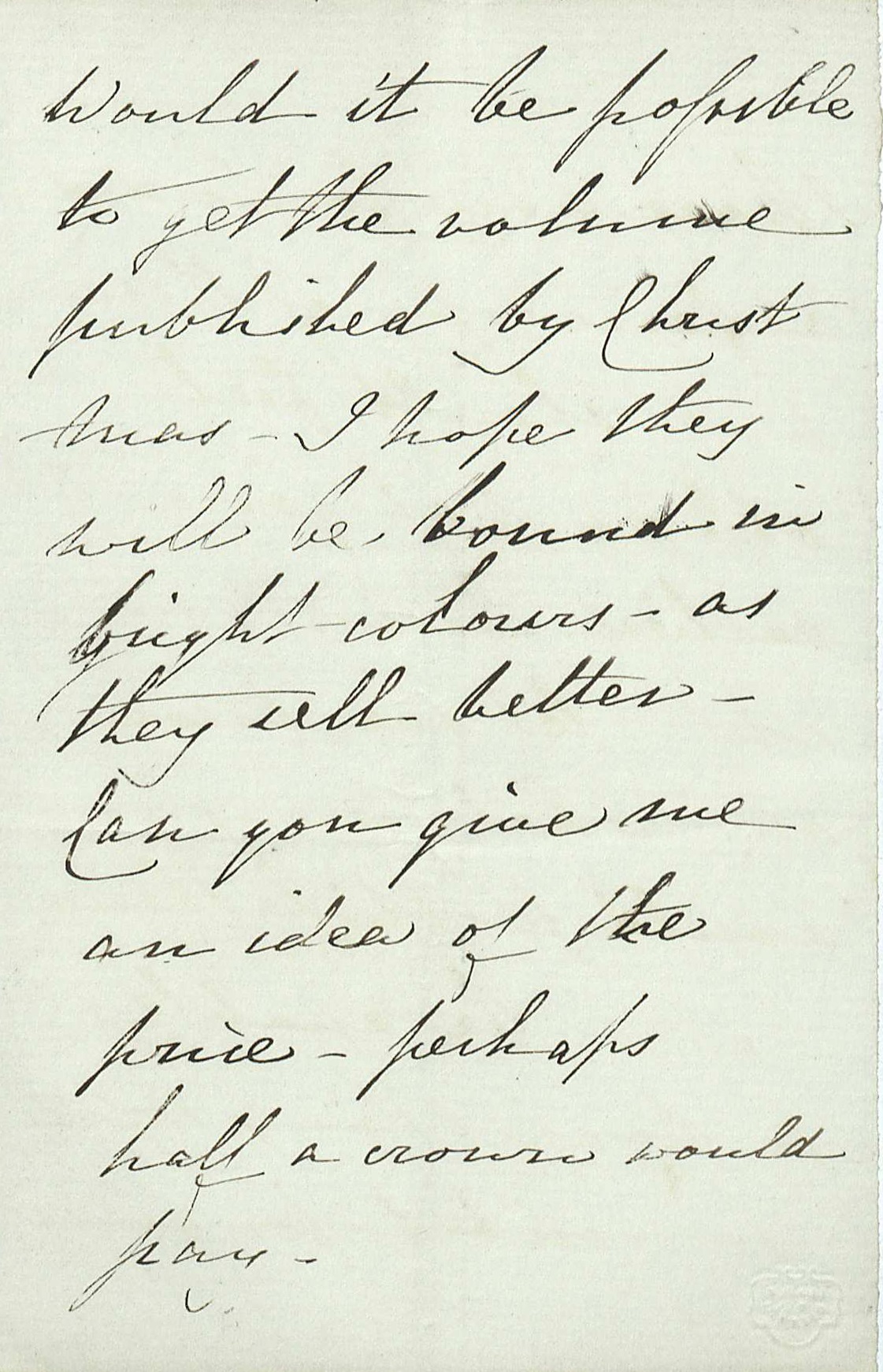

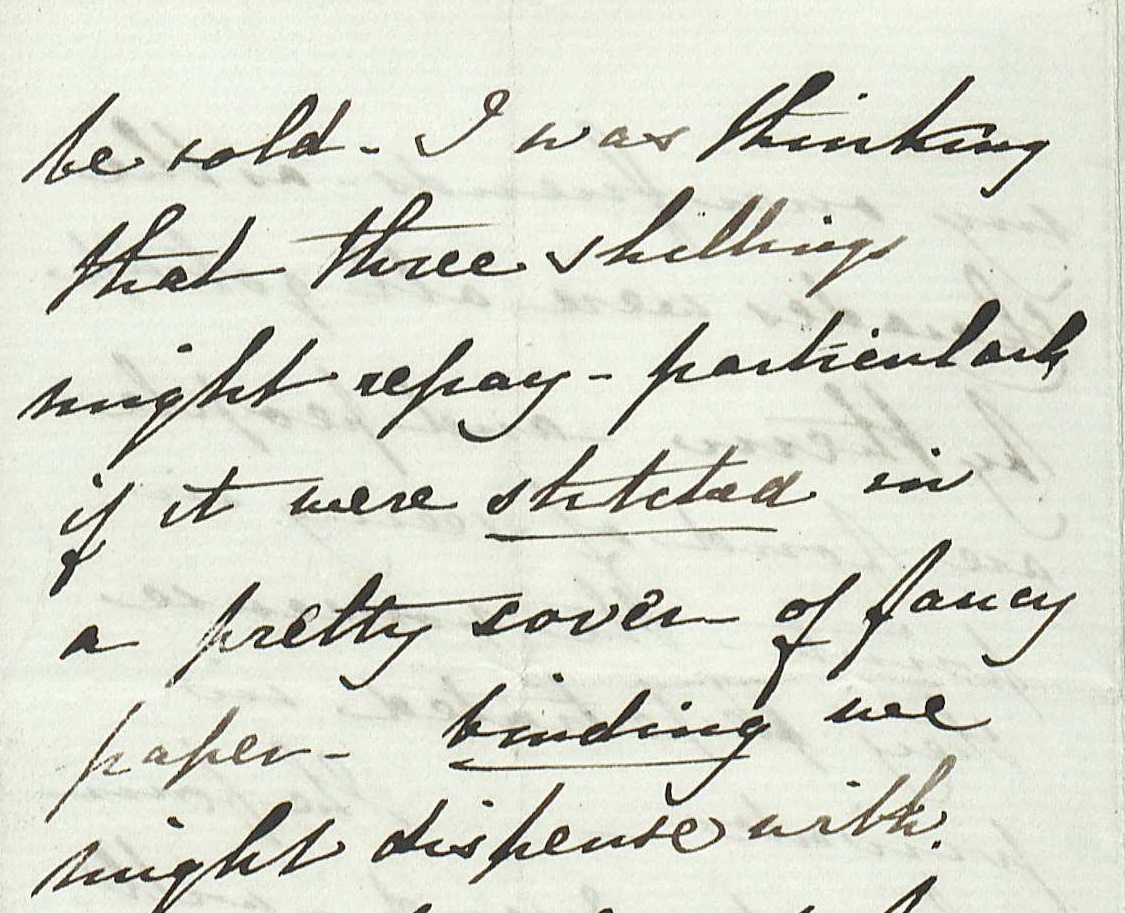

The letters date from the early stage of Keating’s home theatre writing career, as most of her plays date from the 1860s. They are not long, but they reveal her often thoughtful, shrewd, and persuasive business sense in dealing with her publisher. In the first and third letters, she offers suggestions to Lacy about the printing process and pricing. In the first, she writes, “I was thinking that three shillings might repay – particularly if it were stitched in a pretty cover of fancy paper – binding we might dispense with.” In the third letter she states, “I think you do quite right to make the volume of Charades as cheap as you can – for people now like to have a great deal for their money[.] My copies I can sell at the price you mention.” In this letter she includes a postscript noting her further hopes for the timing and color of publication, evidently persuaded by Lacy that binding rather than stitching would suit her work: “Would it be possible to get the volume published by Christmas – I hope they will be bound in bright-colours – as they sell better – Can you give me an idea of the price – perhaps half a crown would pay.” While Keating from the start appears eager to engage in discussions of design and pricing, the continued correspondence suggests that Lacy was an encouraging correspondent.

This passage from the letter dated October 10, 1855 includes the only underlinings that appear in Keating’s letters to Lacy (Image by Elizabeth Ott).

The letters also disclose the role of actual parlour performance in Keating’s own life. Often, her friends are cited as performing her own work. In the first letter she writes: “I shall be enabled to have many copies subscribed for among my own friends – as the Charades were all got up by them – and people are fond of seeing in print – the nonsense they perpetrated in private.” In the third letter, discussing the appropriate order for her plays in the table of contents, she explains that her own personal copy of her plays “is briefly among my private friends.” Having no copy before her, she writes: “I presume the names of the Charade [sic] are very evident – Blue-Beard – Phaeton – Cataline / Guy Fawkes – I forget the order in which they come.” While copies of Blue-Beard exist, I have yet to find any of the other three plays tantalizingly listed here.

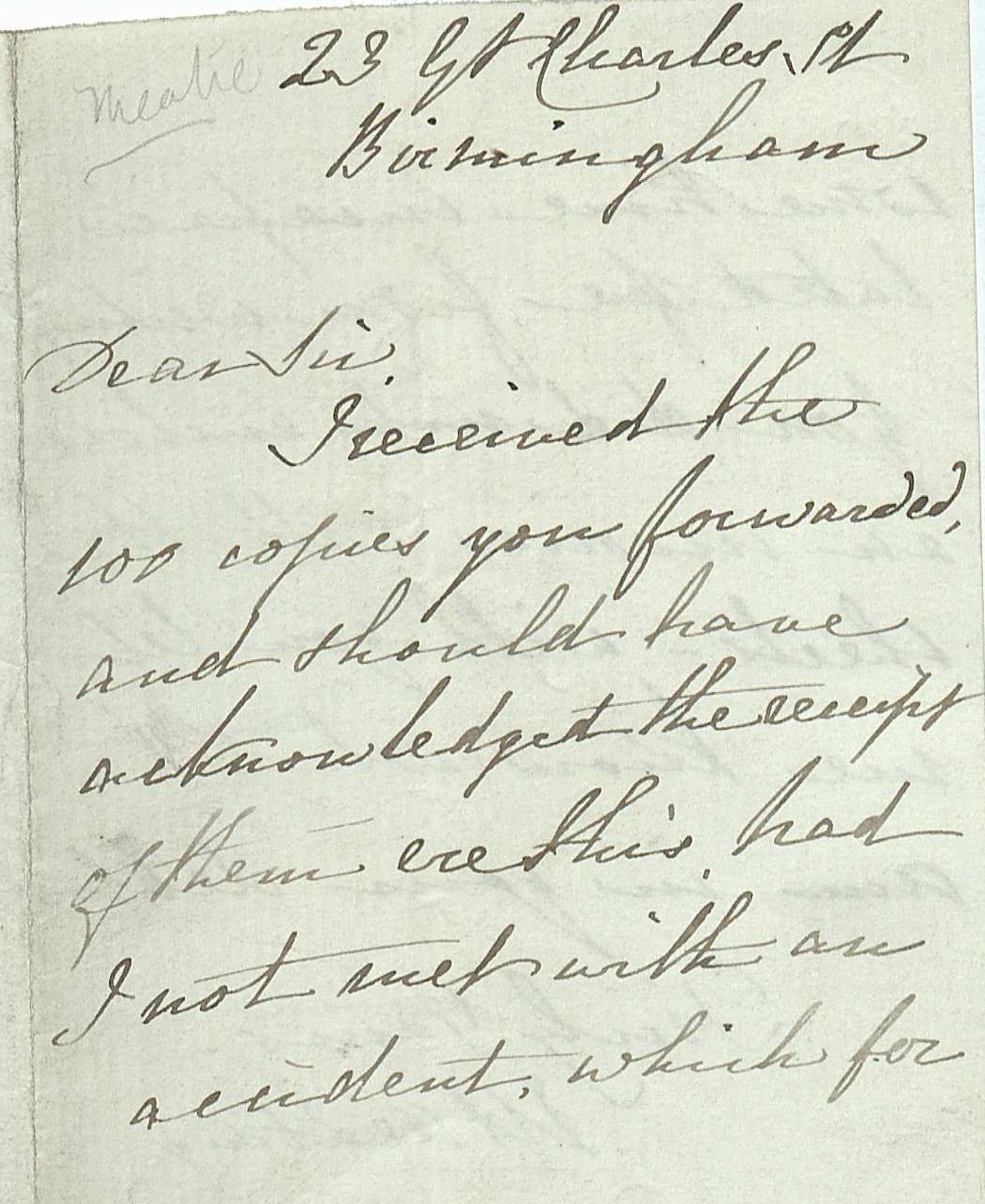

Keating’s second letter makes one curious about other details of her life. She acknowledges having received the “100 copies” forwarded by Lacy, and writes she “should have acknowledged the receipt of them ere this had I not met with an accident which for some time incapacitated me from writing.” To this letter, she adds: “P.S. I directed my friend Mr. Thirlwall to call in Wellingborough for a copy of my Charades – which you will add if you please to my account –.” I suspect she is referring to Connop Thirlwall (1797-1875), who, according to the Dictionary of National Biography was “historian and bishop of St. David’s,” just thirteen miles from Wellingborough. While Keating so kindly offers to add Thirlwall’s book to her own account, I also wonder whether a sort of name-dropping might have come into play here.

Keating alludes, somewhat mysteriously, to an “accident” in this undated letter [1855] (Image by Elizabeth Ott).

If you are interested in learning more about Eliza Keating, stay tuned for the full dissertation-turned-book. Keating is featured in Chapter Two, “A Parlour Education: Reworking Gender and Domestic Space in Ladies’ and Children’s Theatricals,” where I compare her fairy-tale theatricals written for adult performers with Florence Bell’s later 1890s fairy-tale plays written for children. My introductory chapter, the last of my dissertation to be written, discusses Keating’s letters to T. H. Lacy. Thanks to the Small Special Collections Library for making this possible!