This week we are pleased to welcome a guest post by Jacob Shaw, who is a third year majoring in Economics and Sociology.

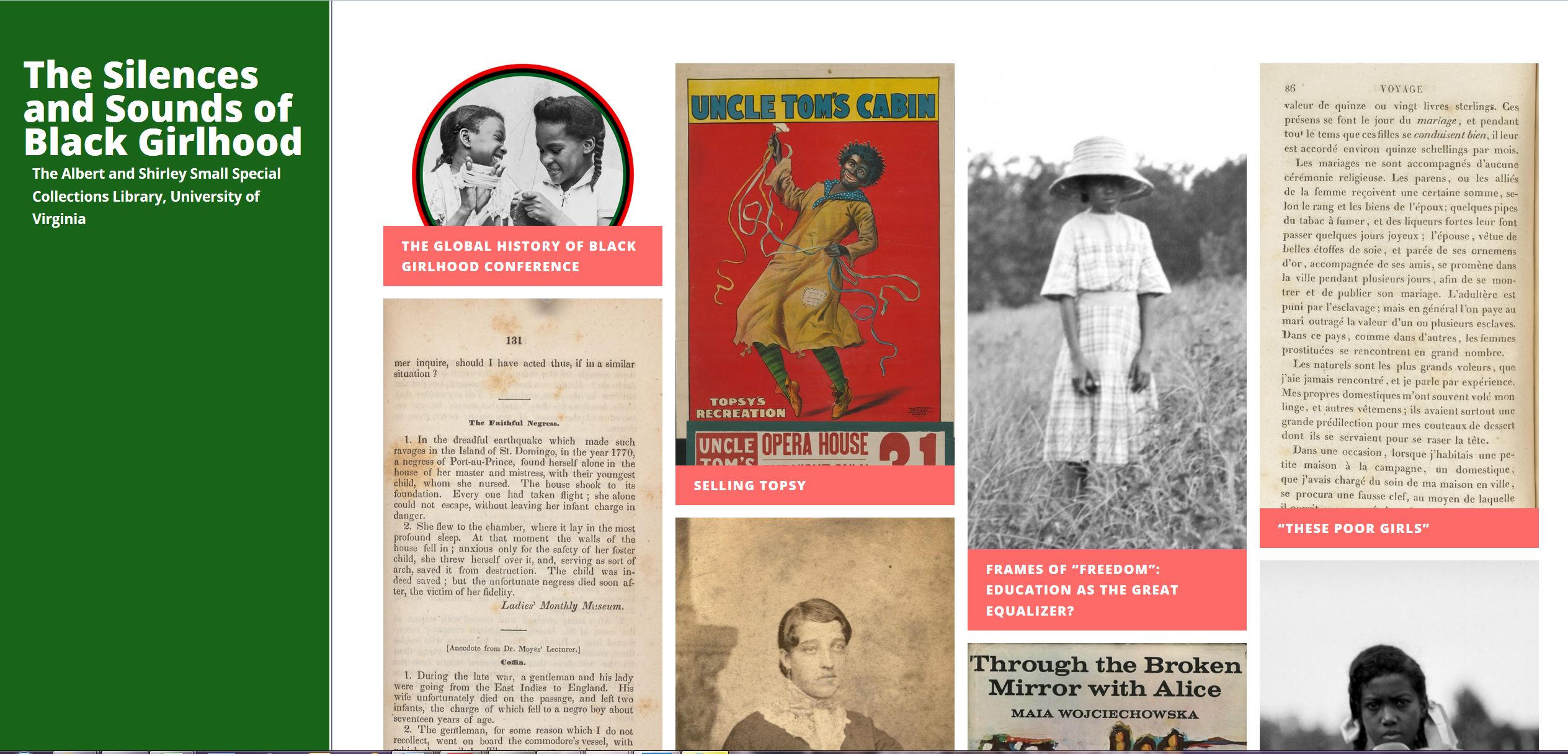

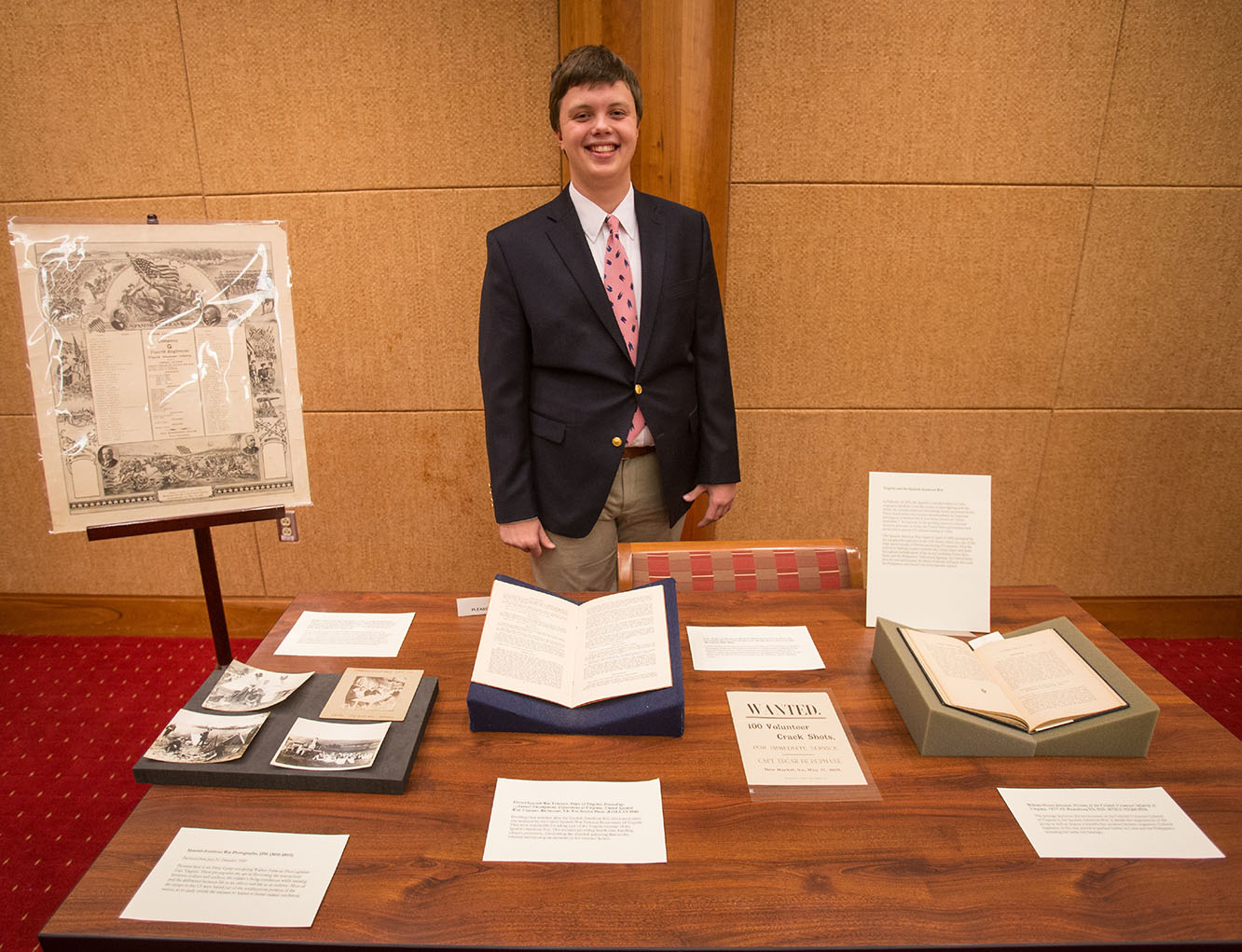

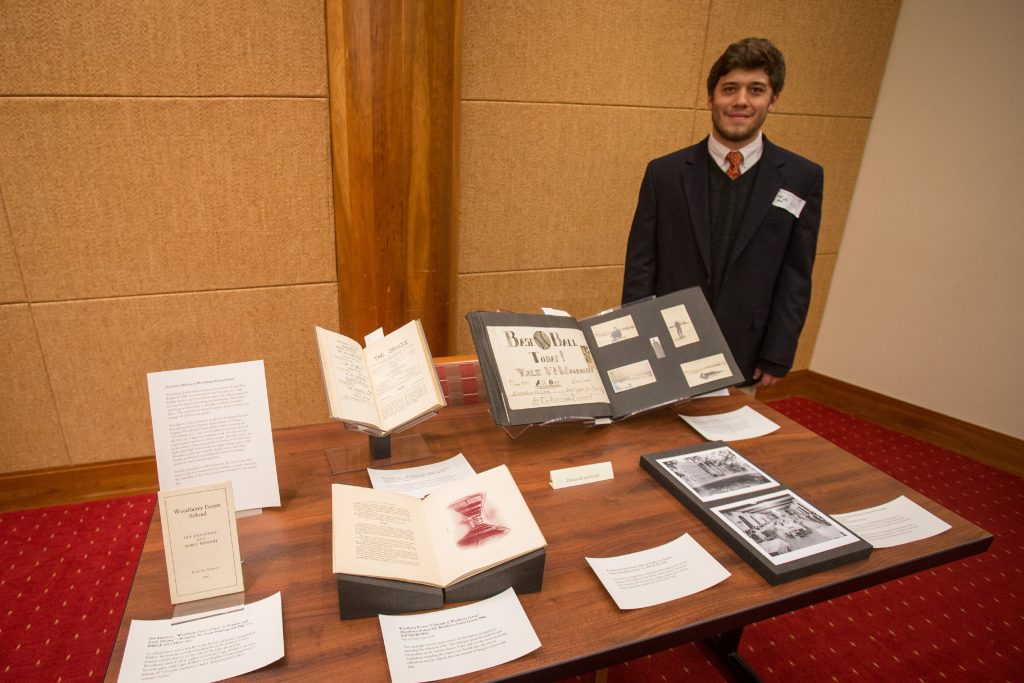

I am one of the two archives project assistants for the Archiving Student Life for the Third Century project at the UVA Archives in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. Funded by UVA Bicentennial, the goal of the project is twofold—to document student life both through making past records of student life visible and accessible, and to expand the collection of records from student groups on Grounds today. In regards to the first goal, we have been working on processing new donations, such as records documenting Greek life and organizations like the Jefferson Society, along with reprocessing and rearranging important record groups and collections. To help expand our holdings of contemporary student groups, my coworker Aasritha Natarajan and I have been reaching out to a variety of student groups via email to inform them about the Archives’ initiative, and to see if they are interested in donating their records. To further engage student groups in the archiving process, we will be hosting a workshop in the Rotunda multipurpose room on April 24th, 5:30-6:30 pm, to talk to students about the project, what we do at the UVA Archives, and how they can preserve their records and donate them to the Archives.

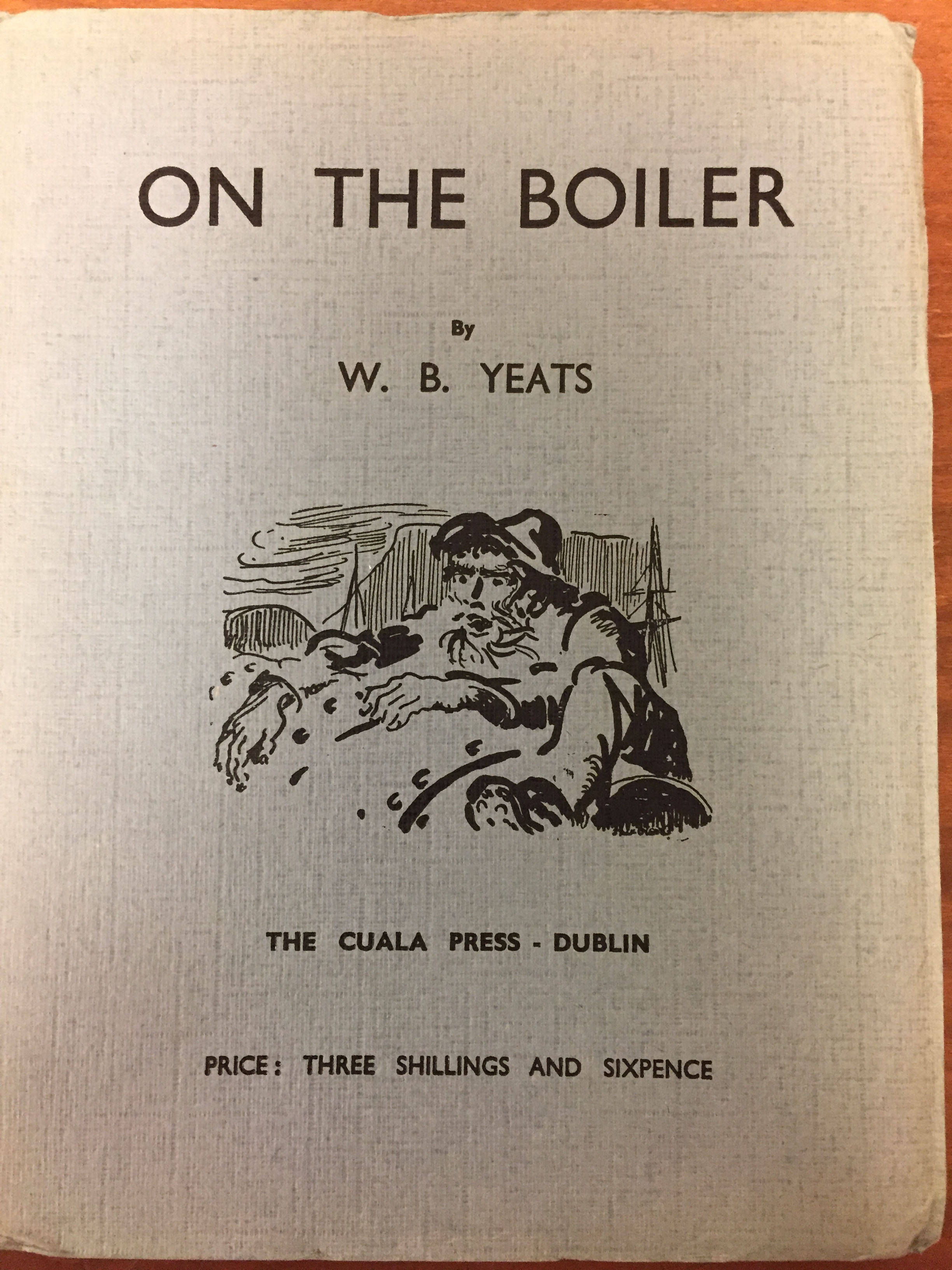

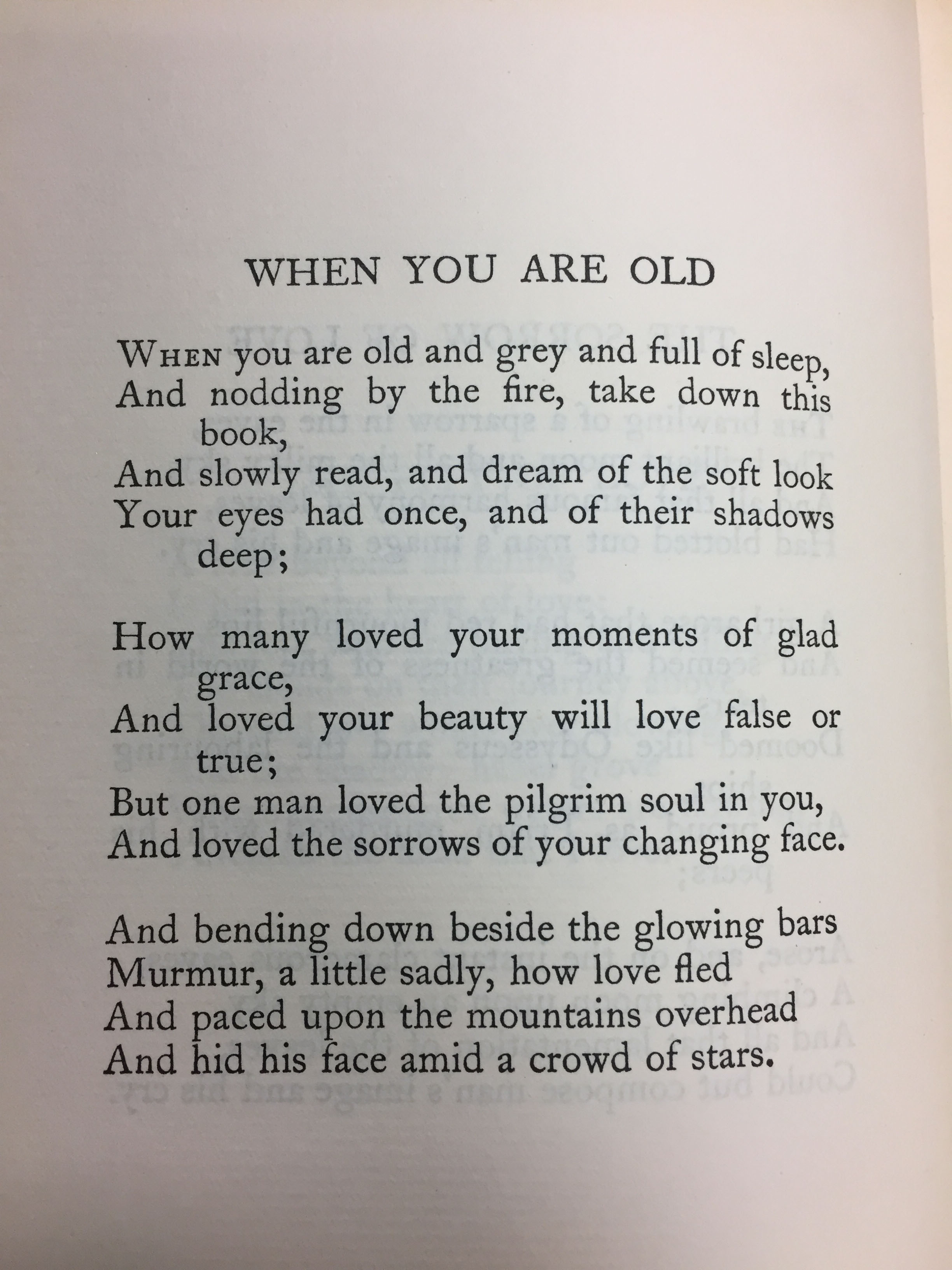

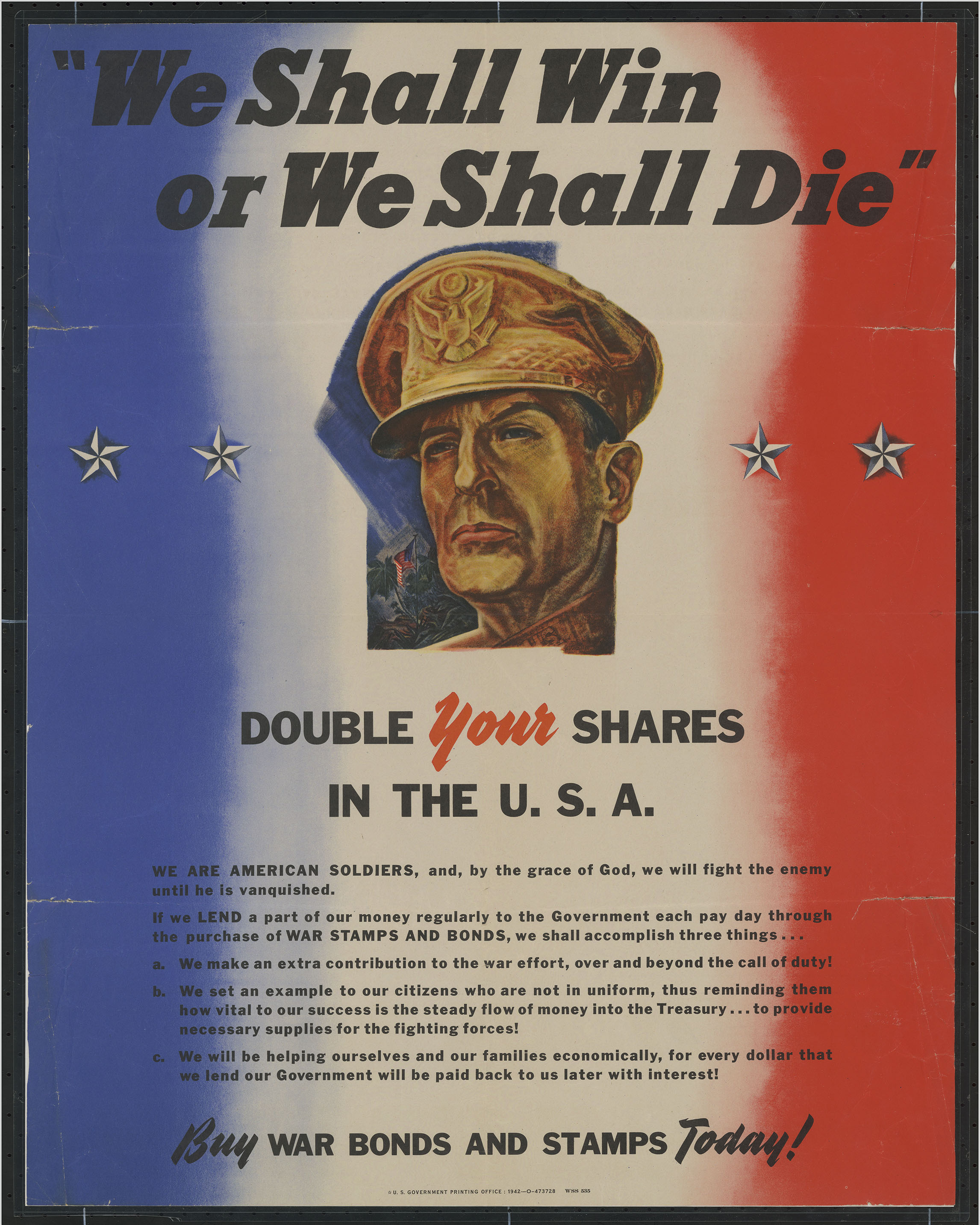

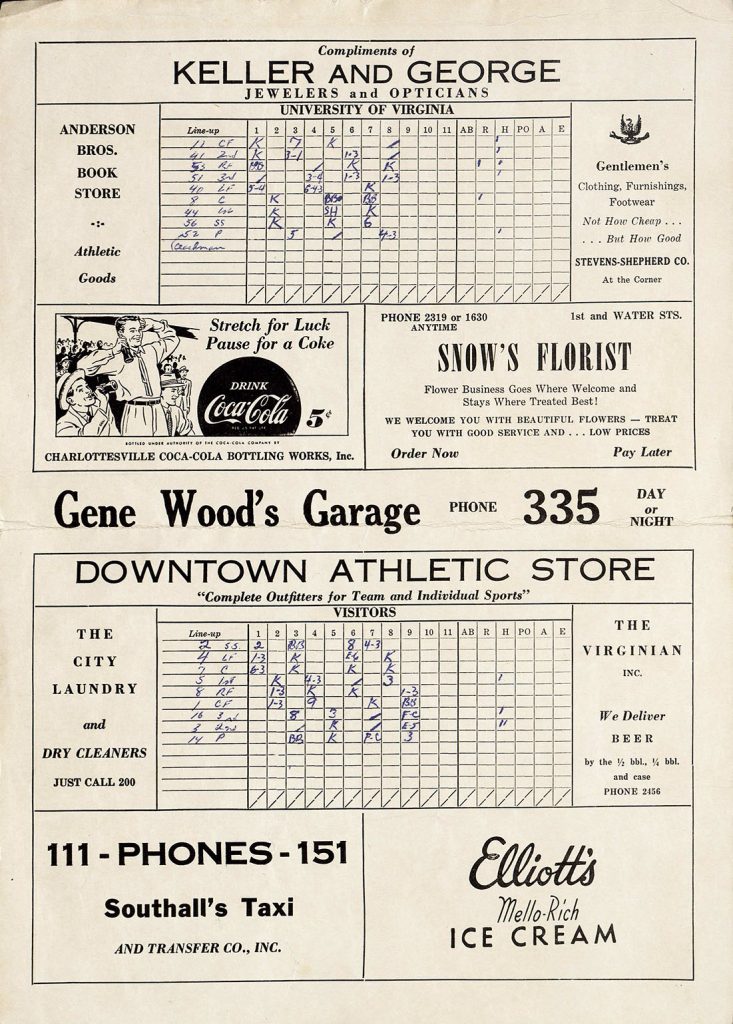

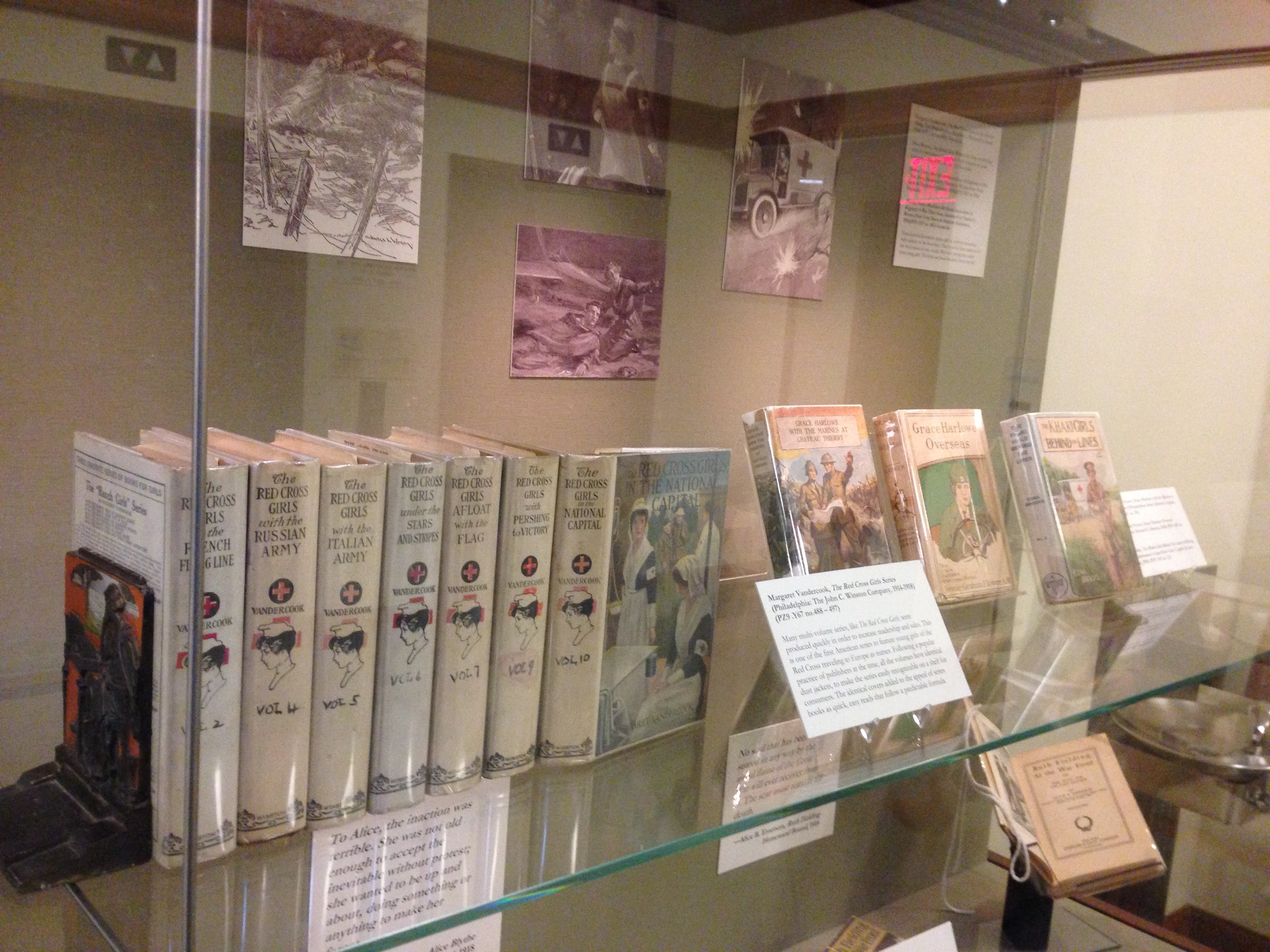

Radical Student Union publication, Southern Student Organizing Committee Records, (MSS 11192, Box 13). Image by Bethany Anderson.

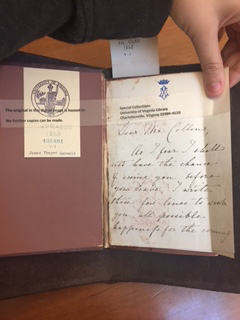

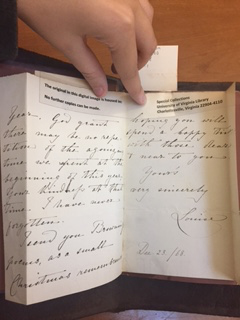

While my coworker and I have both worked on the archiving and outreach ends of this project, I have spent most of my time working with documents and records, both processing and reprocessing. The main group of records I have been working with are the Southern Student Organizing Committee records, a large group of documents that has been compiled by several donors.

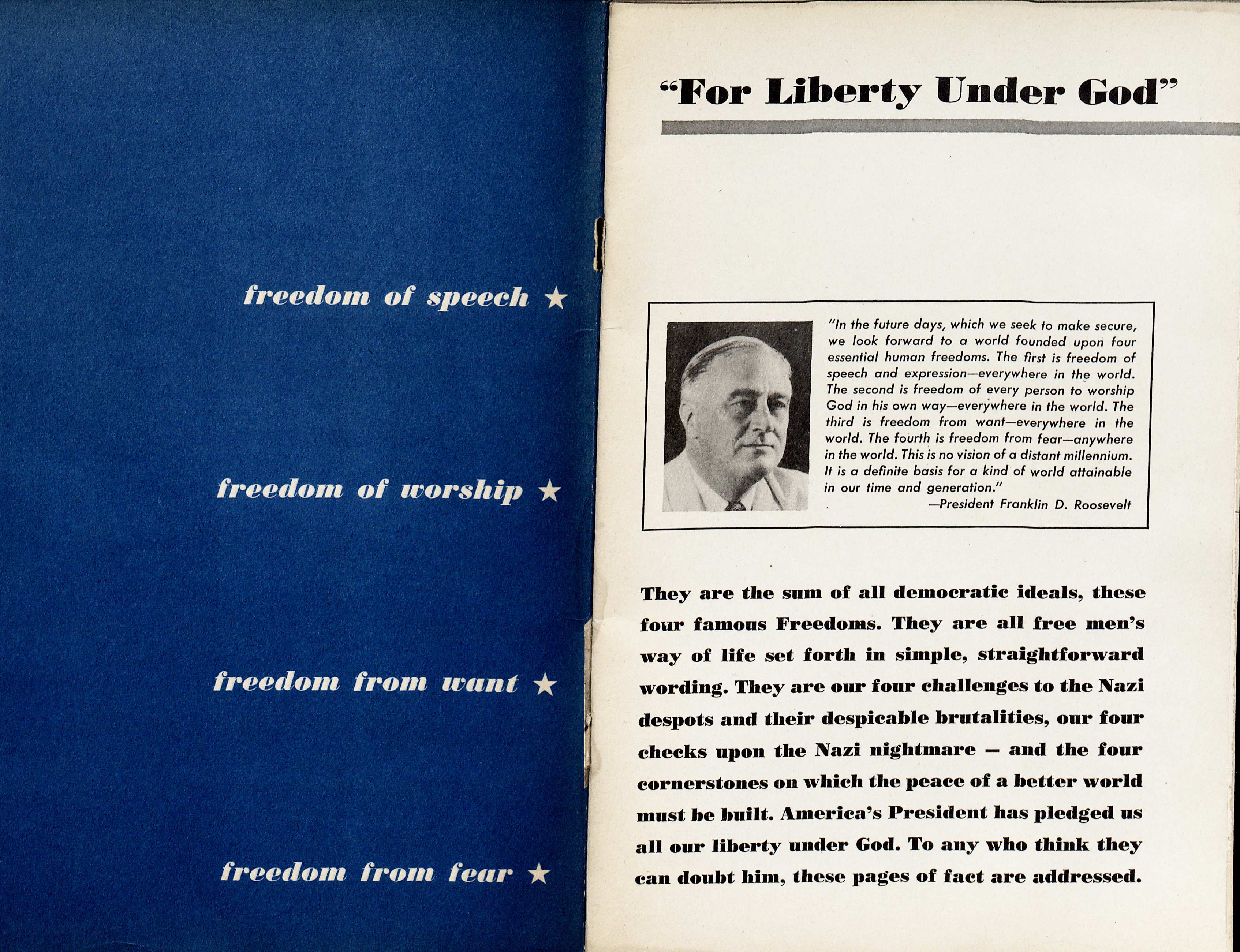

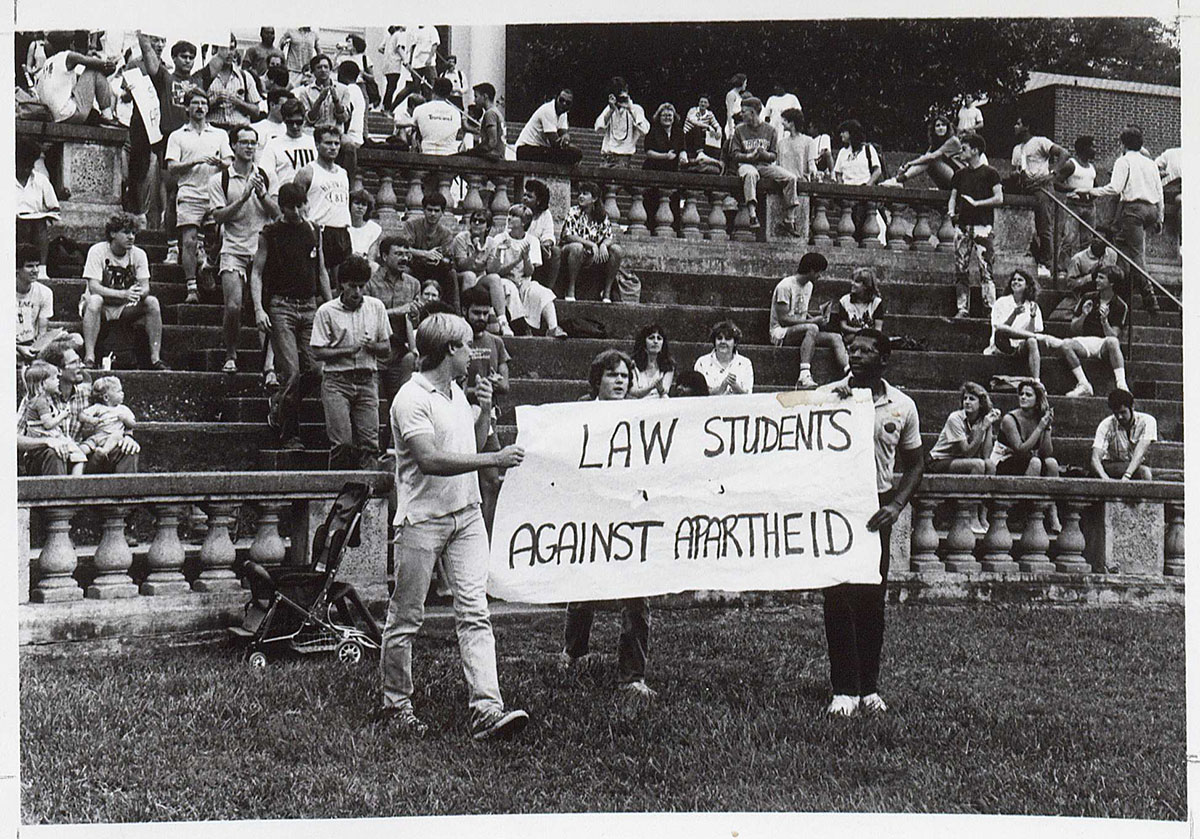

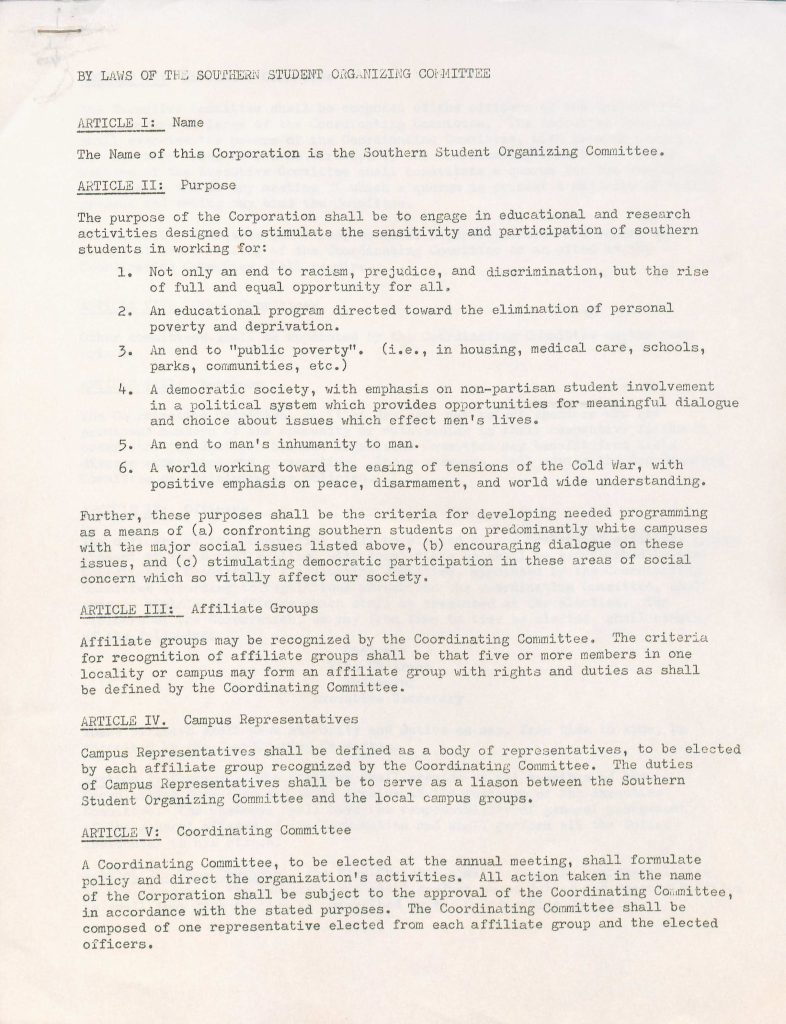

The Southern Student Organizing Committee (SSOC) records tell a very important and interesting story regarding the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War Era, and issues of domestic economic and social policy all through the lens of student activism, particularly at the University of Virginia. The SSOC was an inter-collegiate organization of students at predominantly white universities in the South whose initial aim was to promote progressive social policy regarding racial equality at their universities. While the group remained true to their aims of racial equality in the era of the Civil Rights Movement, they expanded their activism to anti-Vietnam War efforts, by providing legal information to conscientious objectors of the draft and critiquing a variety of American institutions. Also, the group devoted significant energy to supporting labor movements and pushing back against corporate interests. Looking through the documents, it becomes clear that the SSOC was embedded in an important network of student groups, such as the Students for a Democratic Society and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and their different campus chapters, and taking parts in composite organizations such as the Radical Student Union at the University of Virginia.

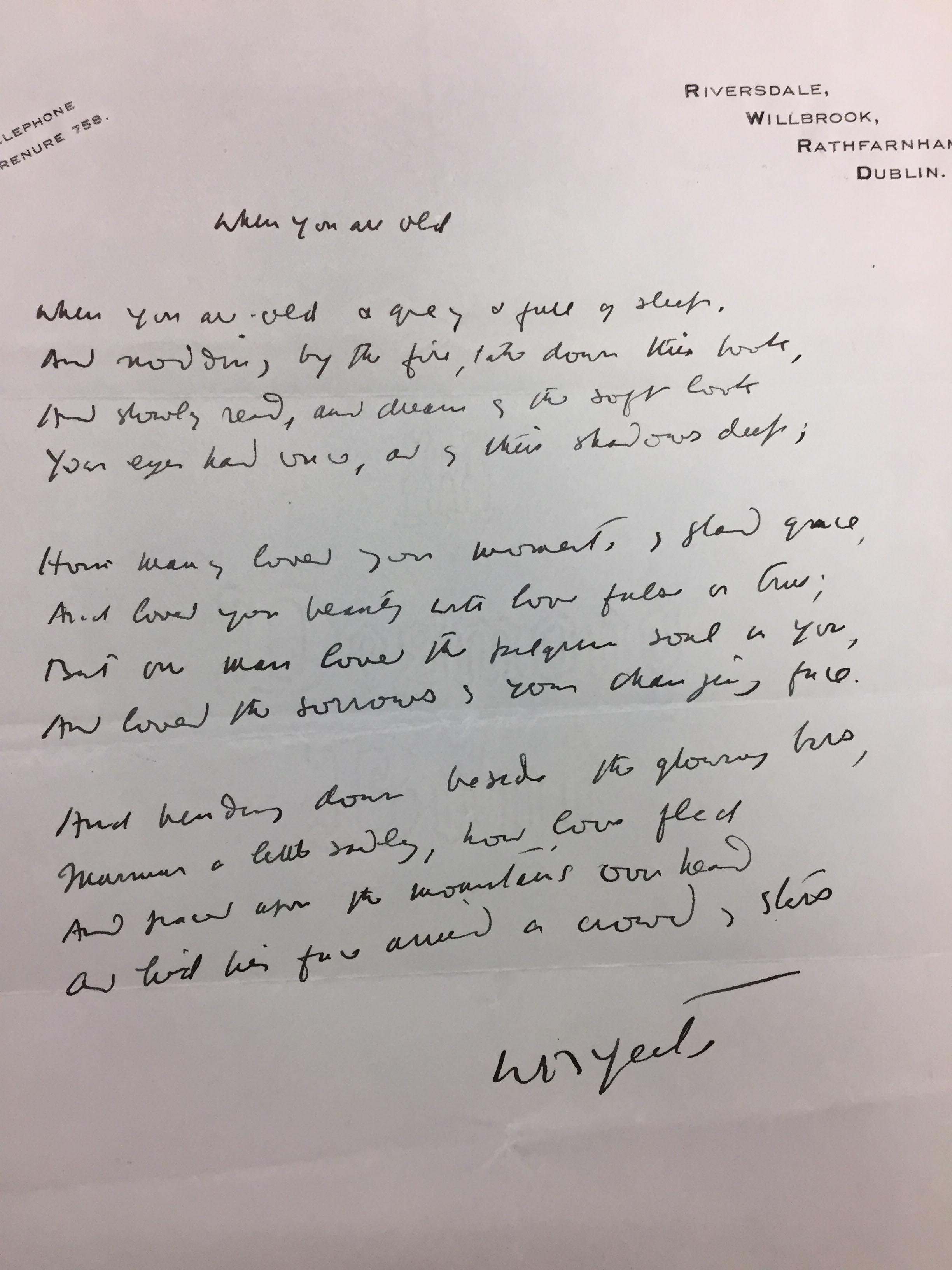

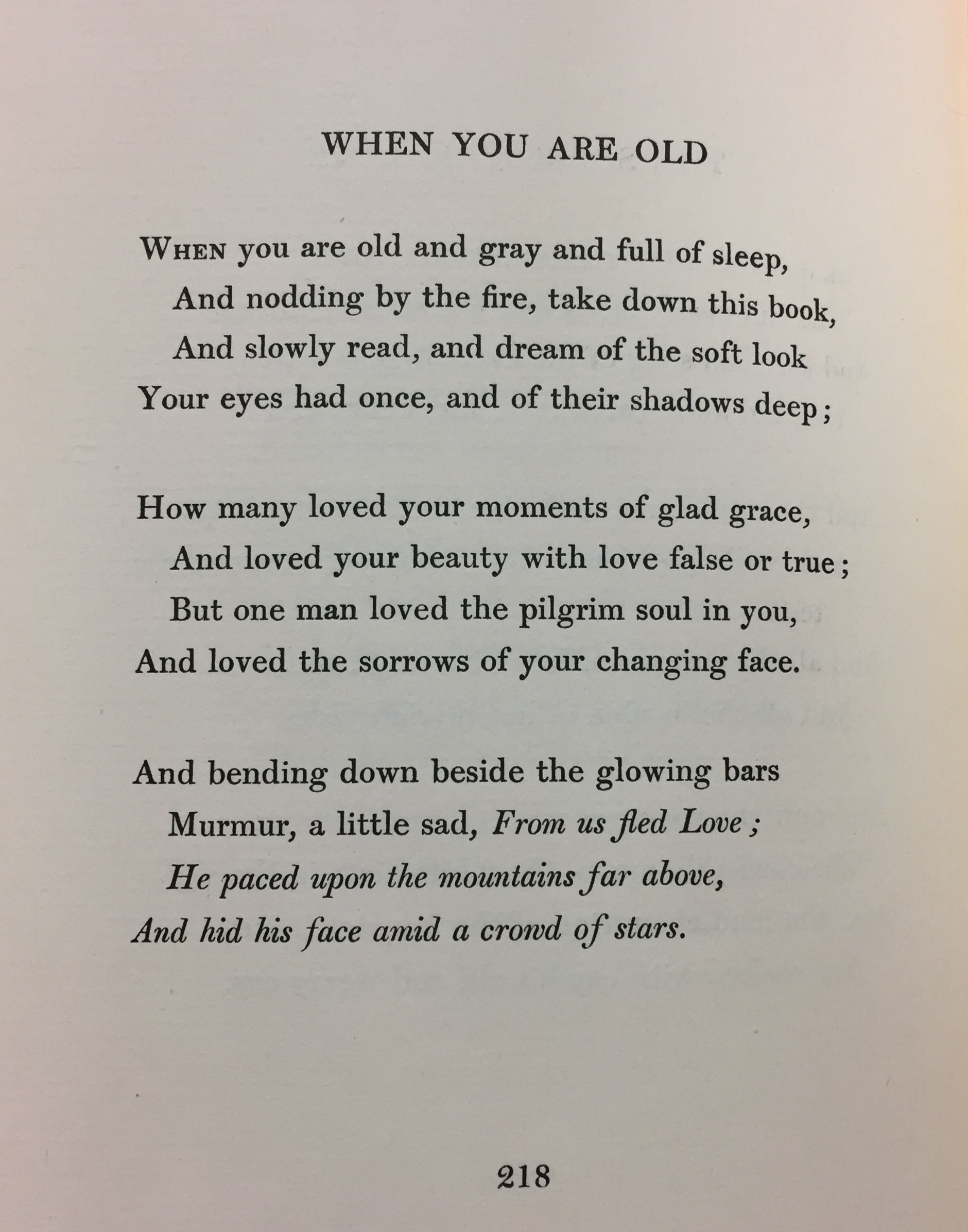

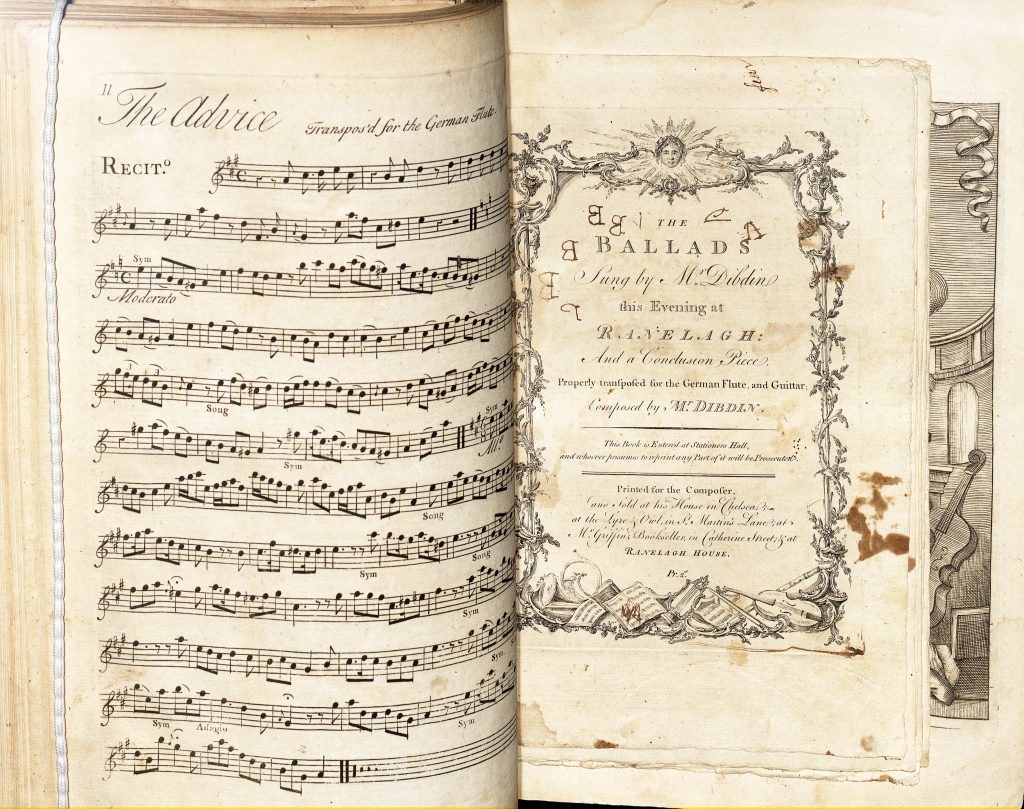

Bylaws of the Southern Student Organizing Committee, Southern Student Organizing Committee records (MSS 11192, Box 12). Image by Bethany Anderson.

The importance of the UVA Archives becomes clear when one realizes that the SSOC almost sank into oblivion, at least in terms of their records. According to Gregg L Michel, a UVA graduate student who wrote about student organizing, many of their records were intentionally destroyed after the dissolution of the SSOC. While writing his dissertation on the SSOC he reached out to two UVA alumni who both served as the chairs of the organization (Tom Gardner and Steve Wise), leading to the donation of their records, along with records from other members they knew. The records donated by Gardner and Wise really bring the story of the SSOC to UVA, as these two figures, particularly Gardner, saw the SSOC through the bulk of their Civil Rights and Vietnam activism, along with a variety of projects that incorporated UVA groups beyond just the SSOC, such as the “Virginia Summer Project” and the Radical Student Union.

The writings of Gardner highlight the local aspects of student activism, with essays and memos discussing issues around grounds and critiquing UVA as an institution.

At our upcoming workshop, I will be talking more about the Southern Student Organizing Committee, and leading the participants through an activity using an example of a document from their records. The goal of the activity will be to think about our current university climate through the lens of the SSOC’s documents, thinking about the state of student activism on grounds today, and understanding the role and importance of the Archives in preserving student life.

Participants will also learn about how to preserve and donate their own records and hear from several students and staff from the UVA Library and Special Collections about their projects that relate to preserving history, identity, and student activity!

Thank you for reading and please consider coming to the Rotunda on April 24th at 5:30 pm. You can register and find more information about the workshop here: https://bit.ly/2TFZK9a