(Note: This is the second of three posts by students enrolled this past Fall in ENNC 3240: Professor Andrew Stauffer’s course in Victorian Poetry. The three students–Heather Jorgenson [read her post here], Ann Nicholson, and Eva Alvarado–elected to participate in a U.Va. Library “Libratory.” Originally proposed by the University Library Committee, and coordinated by Chris Ruotolo, Director of Arts and Humanities for the U.Va. Library, a Libratory is a one-credit library lab attached to selected courses each academic term. Participating students work with their professor and a librarian to undertake a course-related research project involving extensive use of library materials. Heather, Ann, and Eva spent considerable time in Special Collections studying books and manuscripts by a Victorian poet of their choosing. Then each prepared a 20-minute class presentation accompanied by a special exhibition of selected Special Collections materials. They have kindly agreed to share their experiences here. In this post, Ann Nicholson discusses her work on William Butler Yeats.)

As a supplement to Professor Stauffer’s Victorian Poetry class, I had the opportunity to work in the Special Collections Library, where I conducted research on William Butler Yeats, one of the poets that we discussed in class.

My first approach to exploring Special Collections was to look for differences between the “Irish Yeats” and the “English Yeats,” for he moved back and forth between England and Ireland throughout his life. Yeats was born in Sandymount, Ireland on June 13, 1865, and he was proud of his Irish heritage, which is reflected in his early writings, such as The King’s Threshold (1904), a play written for the Abbey Theater in Dublin. Although this play was both published and performed in Ireland, the two editions found in Special Collections were not published in Dublin, but rather by the Macmillan Company in New York and London—showing Yeats’ ability to reach a wider audience beyond simply the people of Ireland.

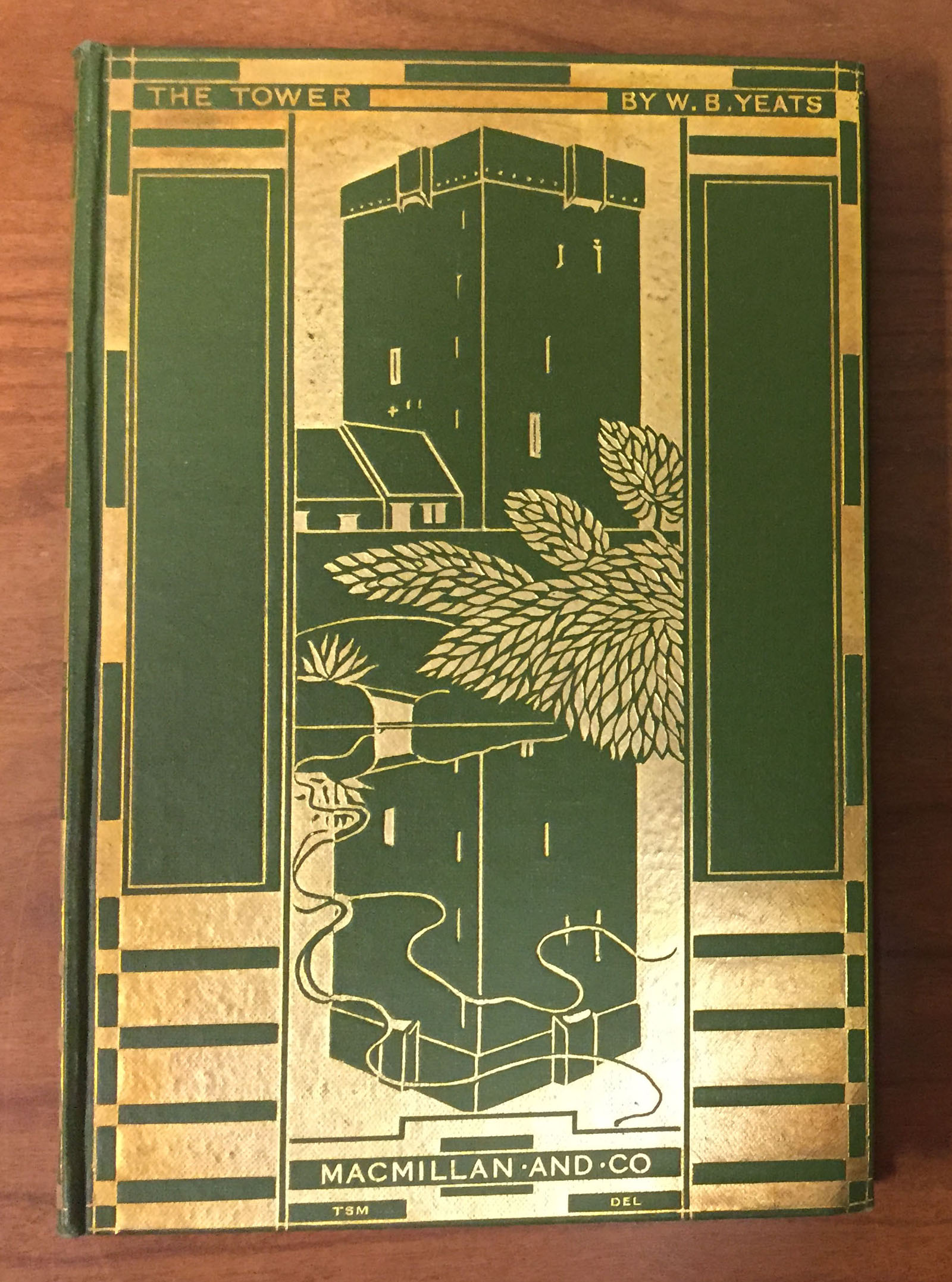

Another work published by Macmillan and found in Special Collections is The Tower, Yeats’ first major collection as a Nobel Laureate after receiving the Nobel Prize in 1923. The title refers to the Thoor Ballylee, a Norman Tower that Yeats purchased and restored in 1917, and where he spent his summers until 1928. Thomas Sturge Moore, an English poet, artist, and long-term friend and correspondent of Yeats, created the cover design. On the light green cloth cover there is a gold woodcut-style image that portrays Thoor Ballylee and its reflection in the water.

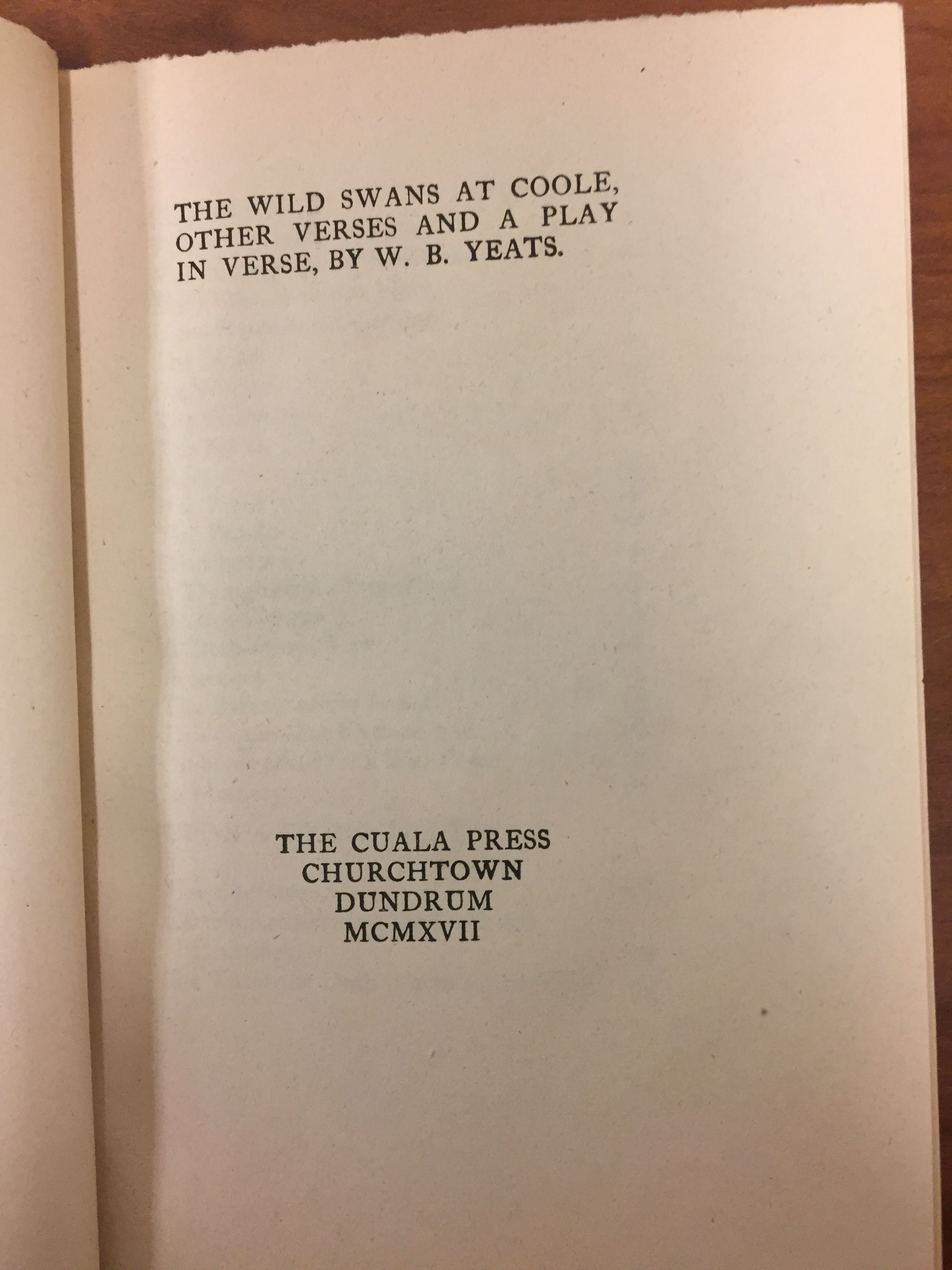

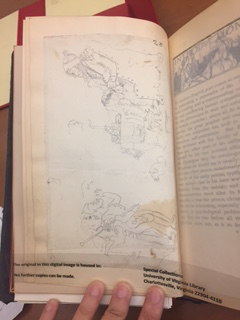

Characteristic Cuala Press typography: a page from W. B. Yeats, The Wild Swans at Coole (Churchtown: Cuala Press, 1917) (PR5904 .W5 1917)

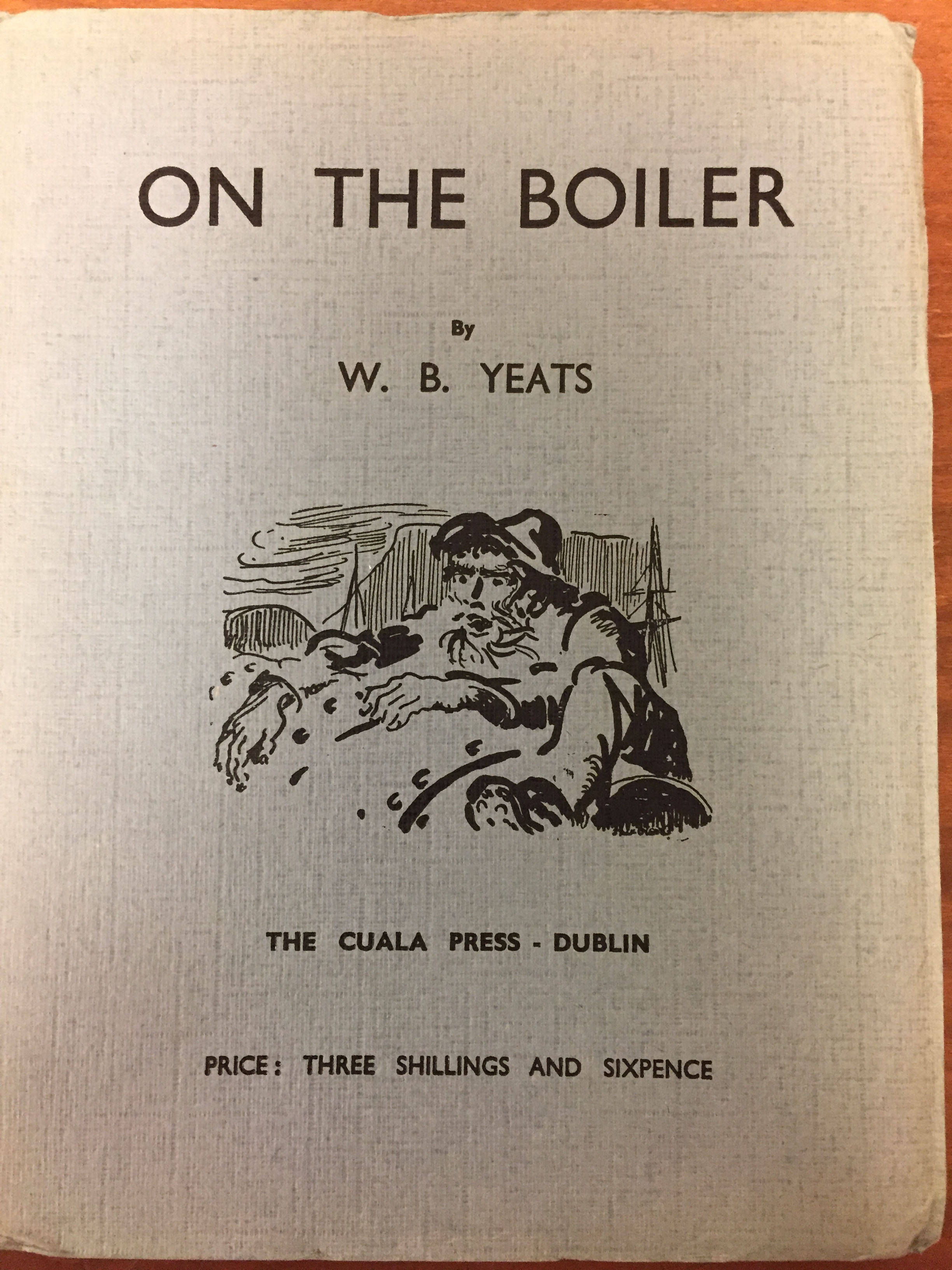

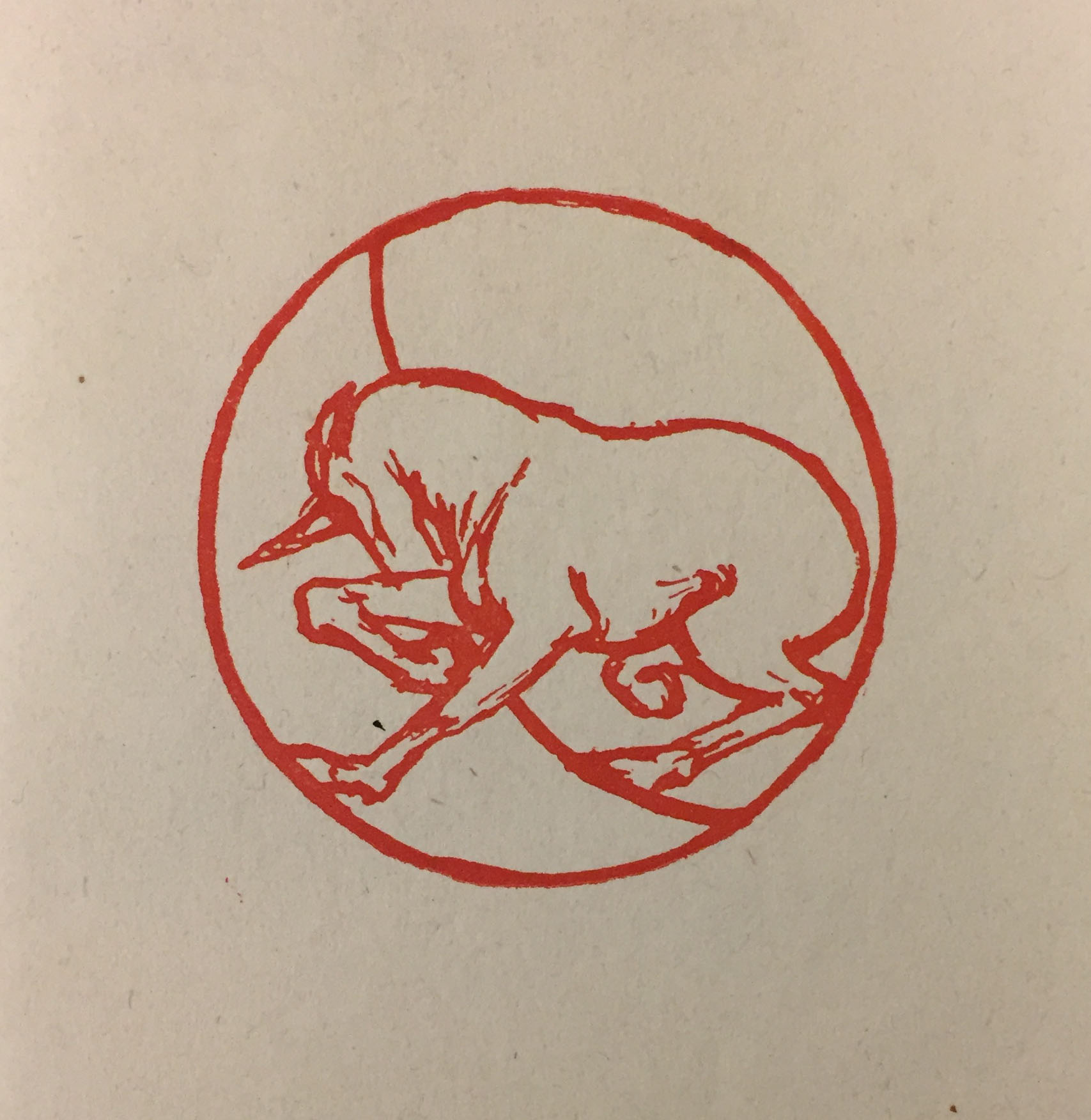

I was particularly interested in finding books published by the Cuala Press, the printing press founded and operated by Yeats’ sister Elizabeth in Dublin. The books printed by the Cuala Press are distinguished by their uniform specifications, such as Caslon Old Face 14-point size font, 22-centimeter height, and blue-grey Ingres paper for the binding. Another characteristic of these books is the use of red ink, such as for the unicorn device found in The Wild Swans at Coole (1917) in Special Collections. This image of a sleeping unicorn was drawn by Robert Gregory, an Irish artist. Another image of a unicorn can be found in Last Poems and Two Plays (1939). An exception to these specifications is On the Boiler (1939), which is a political essay written by Yeats and printed commercially in Dublin by Alex Thom and Co., Ltd. for the Cuala Press. There is a drawing by Jack B. Yeats on the front cover.

An image of a sleeping unicorn, drawn by Robert Gregory, appearing in W. B. Yeats, The Wild Swans at Coole (Churchtown: Cuala Press, 1917) (PR5904 .W5 1917)

Another unicorn image, from W. B. Yeats, Last Poems and Two Plays (Dublin: Cuala Press, 1939) (PR5900 .A3 1939)

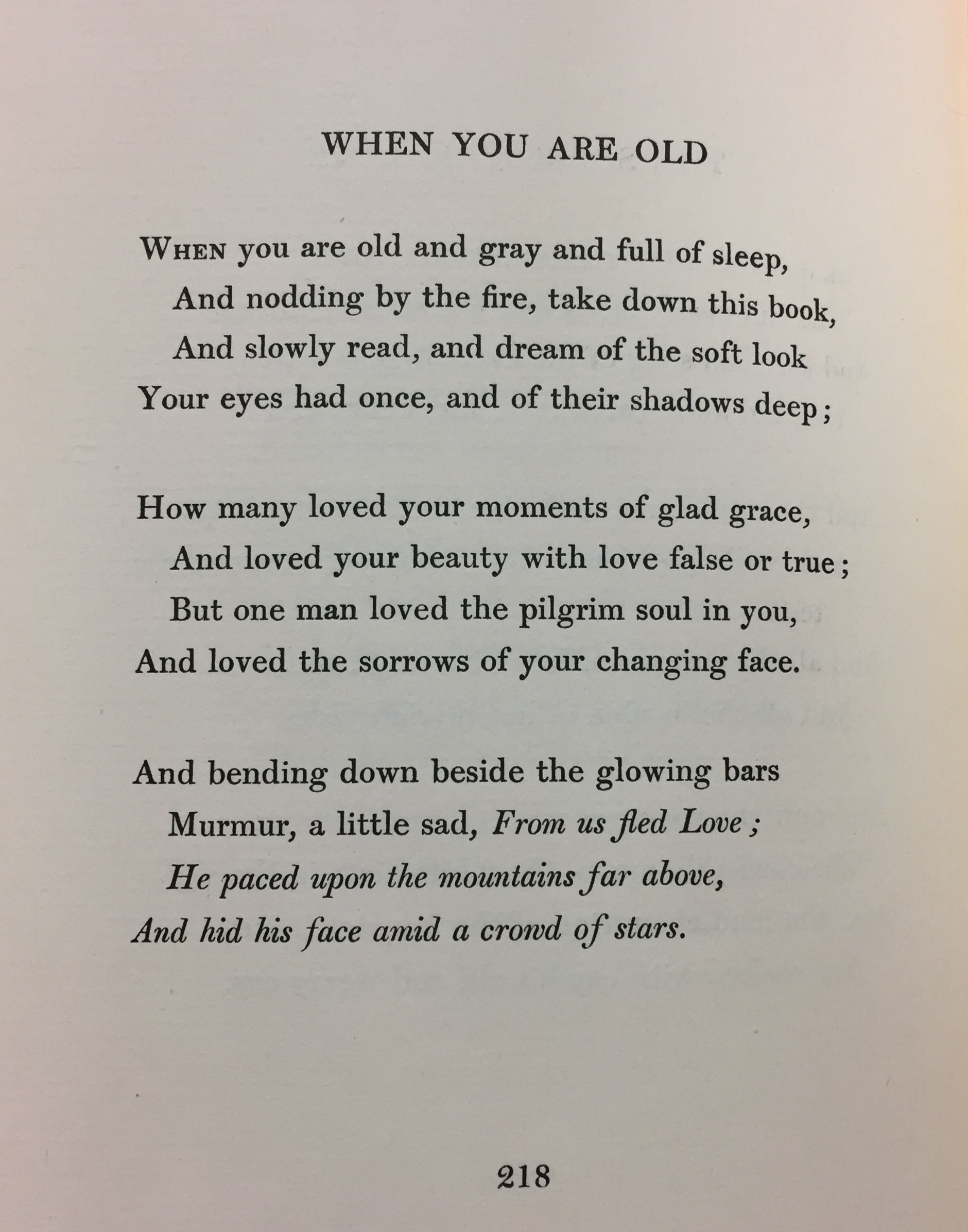

One of Yeats’ poems that we had discussed in class was “When You Are Old,” and so, I was also hoping to find books in Special Collections that contained this poem. In addition to finding it in multiple sources, including The Macmillan Company’s Poems (1895) and T. Fisher Unwin’s Early Poems and Stories (1925), I discovered that Special Collections also has an autograph manuscript. I also noticed discrepancies between the different publications of the poem, which sparked another area for me to explore.

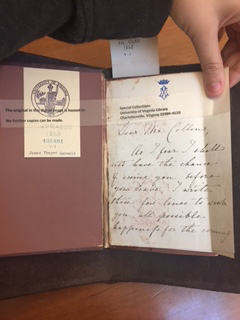

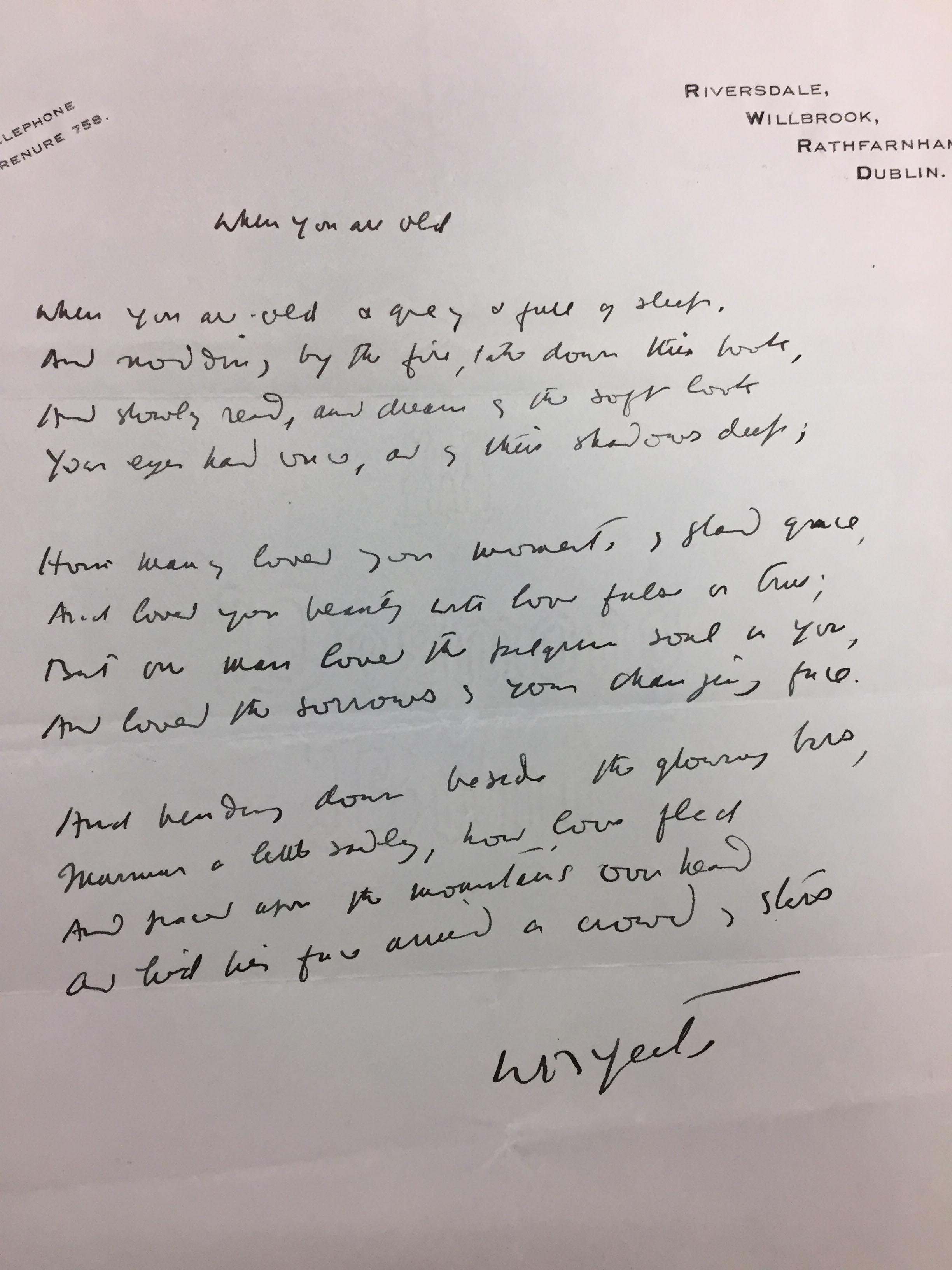

A manuscript of the poem “When You Are Old,” written and signed by William Butler Yeats sometime during the 1930s, per the printed address. (MSS 4243)

Yeats wrote the poem “When You Are Old” following the rejection of his marriage proposal by the beautiful actress Maud Gonne in 1891. The poem first appeared in The Countess Kathleen and Various Legends and Lyrics, which was published in 1892 by T. Fisher Unwin in London, and reprinted in 1893 by Roberts Bros. in Boston. In both publications the poem stands alone as an uncollected work. However, the lyrics were revised and collected under the title “The Rose” before the first edition of Yeats’ Poems was published 1895 by T. Fisher Unwin. Yeats again revised the poem for the 1899 edition of Poems. Poems was reprinted again in 1901, 1904, 1908, 1912, 1913, 1919, and 1920 with no revisions made to “When You Are Old.” In the prefaces to the 1912 and 1920 editions of Poems, Yeats writes that “he ha[s] not again retouched the lyric poems of my youth,” thus the 1901 text of the poem “When You are Old” became the standard version. This can be further confirmed in other publications of the poem, such as Macmillan and Co’s Early Poems and Stories (1925), which contains the same version of the poem.

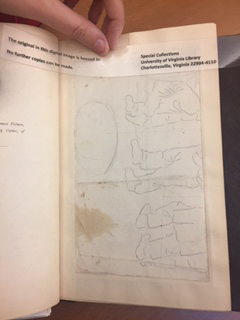

Original version of the poem, “When You Are Old,” as it appears in W. B. Yeats, Poems (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1895) (PR5900 .A3 1895)

The autograph manuscript in Special Collections of “When You Are Old” lacks a date, but it contains a telephone number in the top left corner and the address Riversdale, Willbrook, Rathfarnham, Dublin—the address of Yeats’ last Irish home that he signed the lease for in July 1932. He lived at this home with his wife, George, and two children Anne and Michael, and it was also the setting for his last meeting with Maud Gonne in the summer of 1938. In addition to Yeats’ home address being an indicator of time, letters written by Yeats on the same stationery can help confirm the date of the manuscript. For example, there is a manuscript currently located at the National Library of Ireland that is a 1935 correspondence between W.B. Yeats and Lennox Robinson. Furthermore, another factor used in determining the manuscript’s date is the text itself, for it is the standard version.

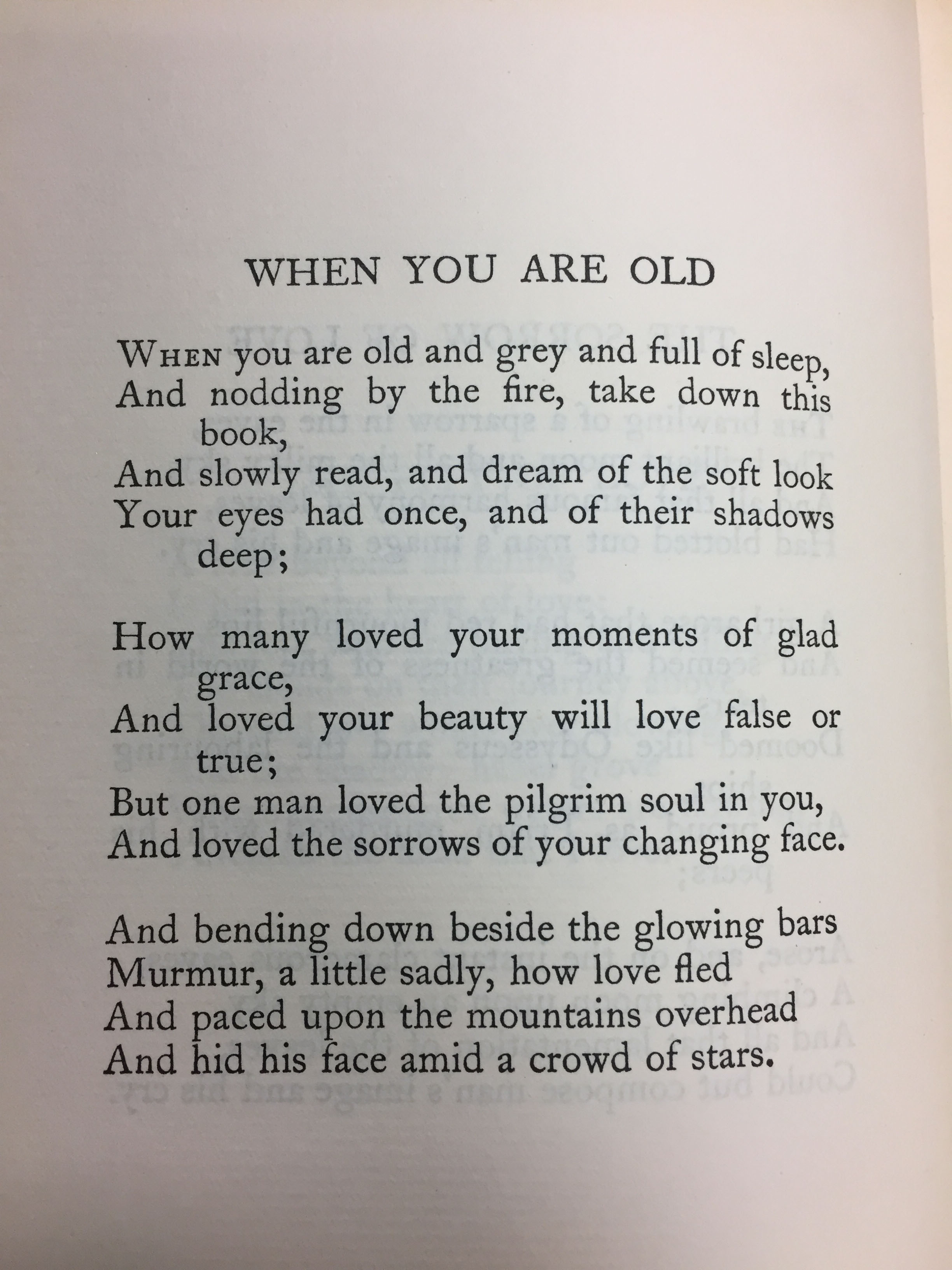

Revised version of the poem, “When You Are Old,” as it appears in W. B. Yeats, Collected Works in Verse and Prose (Stratford-on-Avon: Shakespeare Head Press, 1908) (PR5900 .A3 1908 v.1). Note the changes to the last stanza; the same changes appear in the manuscript (shown above).

Above are images of the poem “When You Are Old” as it appears in Poems (1895), in The Collected Works in Verse and Prose (1908), and in the manuscript (post-1932).

― Ann Nicholson