Welcome to another story about one of the many interesting collections in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia. I am Ellen Welch, an Archives processor and an Albemarle County local who enjoys sharing knowledge about historical collections, particularly those from Charlottesville and Albemarle County. This is a post about Hugh Carr (1843-1914) and his family who were African American owners of the land where Ivy Creek Natural Area in Charlottesville and Albemarle County, Virginia sits today. Part of my work is responding to suggestions for improvements in describing our collections. My colleague, Katrina Spencer, Librarian for African American and African Studies, recently sent me a request to add more description to the Ivy Creek Natural Area collections MSS 10770, and MSS 10176.The description was so minimal that the African American history of the Carr family was invisible to anyone searching our collections. With the suggestion from Katrina, I was able to bring the Carr family history into the description so that patrons can know more about this important family in Albemarle County during the nineteenth century.

The Ivy Creek Natural Area—which is well known for its beautiful views of the Blue Ridge mountains, and its numerous hiking trails, and nature programs—was created in 1978 from the sale of the Carr land. Hugh Carr, born into enslavement, purchased the River View Farm after emancipation in 1870. He doubled the acreage of the farm and built a farmhouse where he raised his family through four generations. The local government, the Nature Conservancy, and the Ivy Creek Foundation preserved this property, making it a National Historic Landmark, and recovered a treasure of local history that memorializes the lives of the Carr family. As a longtime local resident, I had known about the Ivy Creek Natural Area but had no knowledge of Hugh Carr. Similarly, the description in the collection title made no mention of Hugh Carr or River View Farm. This is what makes reparative work so essential in libraries and historical repositories. It is exciting to shine a light on their remarkable lives, making them well known to our patrons today and in the future.

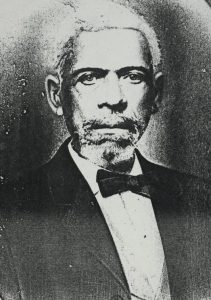

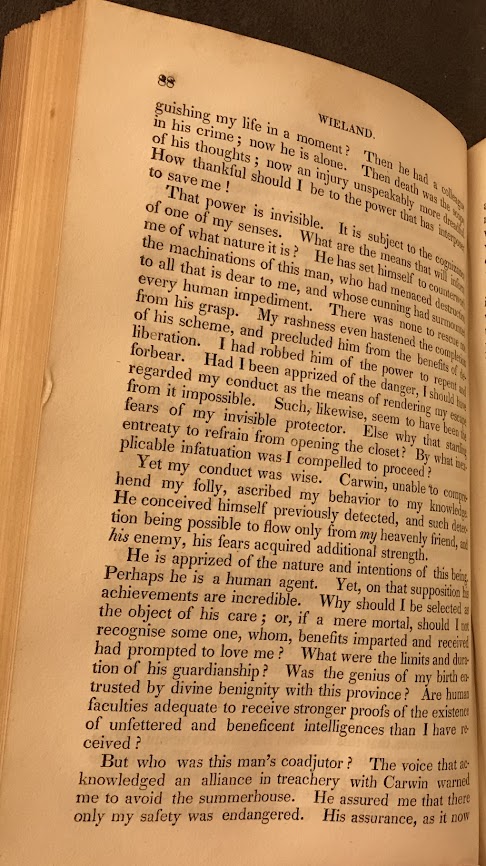

The collections, Papers of the Ivy Creek Foundation and its history of Hugh Carr’s River View Farm, MSS 10770-a , MSS 10176 introduce Hugh Carr (1843-1914), an African American born in enslavement, who bought a 58-acre tract of land for $100, which became River View Farm (Martin Tract from John Shackelford) in Albemarle County in 1870 after emancipation. Hugh Carr continued to purchase land for the farm, and, by 1890, it was over 200 acres, making Carr among the largest African American landowners in Albemarle County. (Brickhouse)

Aerial view of Hugh Carr’s “River View Farm.” Hugh Carr and Ivy Creek Natural Area papers MSS 10770-a Box 1, Folder 11

Receipt for Hugh Carr’s purchase of the land for his farm. Hugh Carr and Ivy Creek Natural Area papers, MSS 10176-a Box 1, Folder 1

The Carr family and their descendants were excellent farmers, modeling the best agricultural practices for other farmers. According to Hugh Carr’s grandson, Dr. Benjamin Whitten, the farm had “horses, milk, and beef cattle, a flock of sheep, pigs, chickens, and crops. They also worked other jobs, while farming their land, waking at 3 a.m. to begin their work every day. (Brickhouse)

Barn at River View Farm, which can still be visited today at Ivy Creek Natural Area, which is located 6 miles from the City of Charlottesville going west on Hydraulic Road toward the South Rivanna Reservoir, off a left turn before the Reservoir bridge. Hugh Carr and Ivy Creek Natural Area papers, MSS 10770-a Box 1, Folder 11

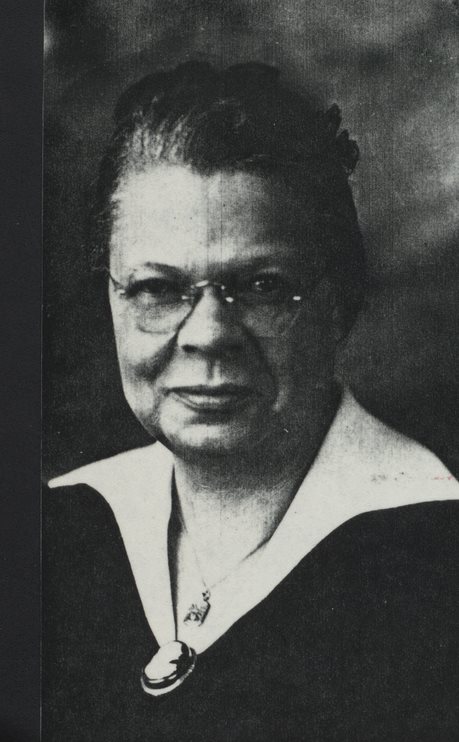

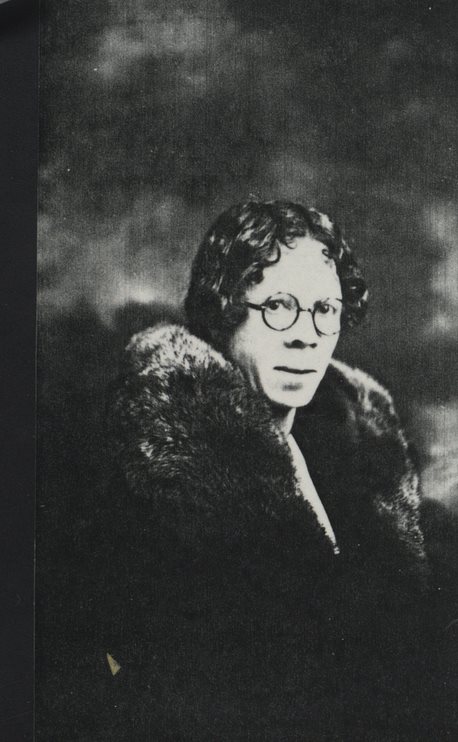

Hugh Carr married his first wife, Florence Lee in 1865 when they were still enslaved by Richard H. Wingfield of Woodlands Plantation. After two years, she left Carr, and they were eventually divorced. Hugh Carr married Texie Mae Hawkins (1865-1899) in 1883. They had six daughters, Mary Carr Greer (1884-1973), Fannie Carr Washington (1887-?), Peachie Carr Jackson (1889-1977), Emma Clorinda Carr (1892-1974), Virginia Carr Brown (1893-1935), and Ann Hazel Carr (1895-1975), and one son Marshall Hubert Carr (1886-1916).

Hugh Carr, who did not know how to read and write, highly valued education for his daughters and son. He raised them by himself after Texie Mae died in 1899. Most of his children earned college degrees and post graduate degrees, becoming teachers and community leaders. Six of the Carrs’ seven grandchildren, ten of thirteen great grandchildren, and nine of twelve great-great grandchildren graduated from college. (National Register of Historic Places Registration Form)

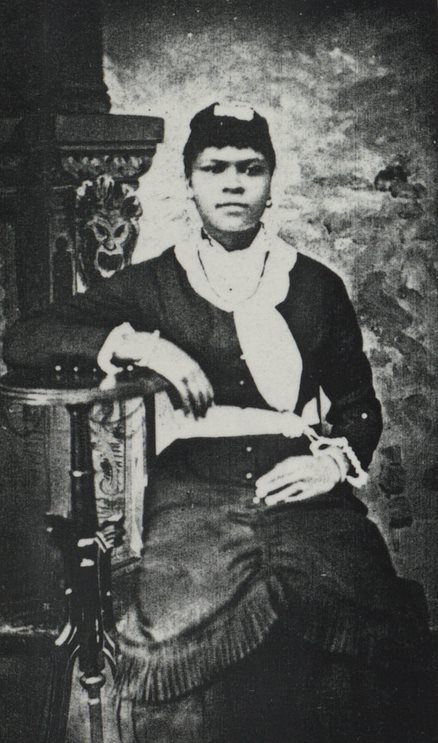

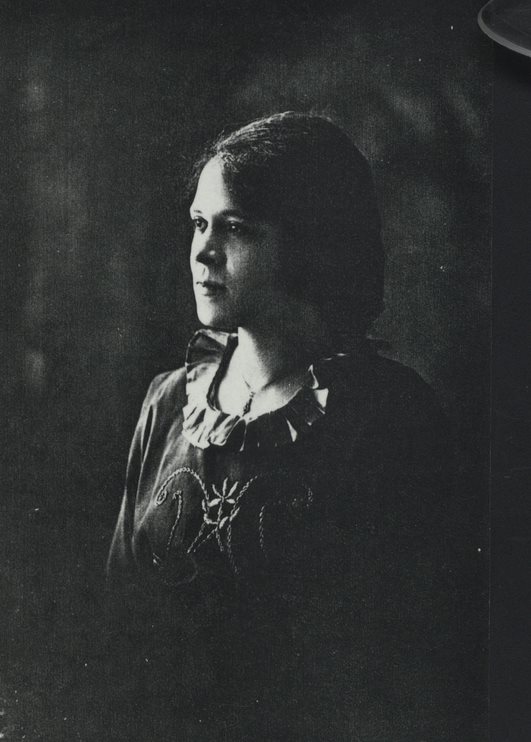

Mary Carr Greer , daughter (1884-1973). Teacher and Principle who invited students to stay at her house, which was near the Albemarle Training School, during bad weather. Hugh Carr and Ivy Creek Natural Area papers, MSS 10770-a Box 1, Folder 11

Fannie Carr Washington, sister. Hugh Carr and Ivy Creek Natural Area papers, MSS 10770-a Box 1, Folder 11

Peachie Carr Jackson (1889-1977) daughter. Hugh Carr and Ivy Creek Natural Area papers, MSS 10770-a Box 1, Folder 11

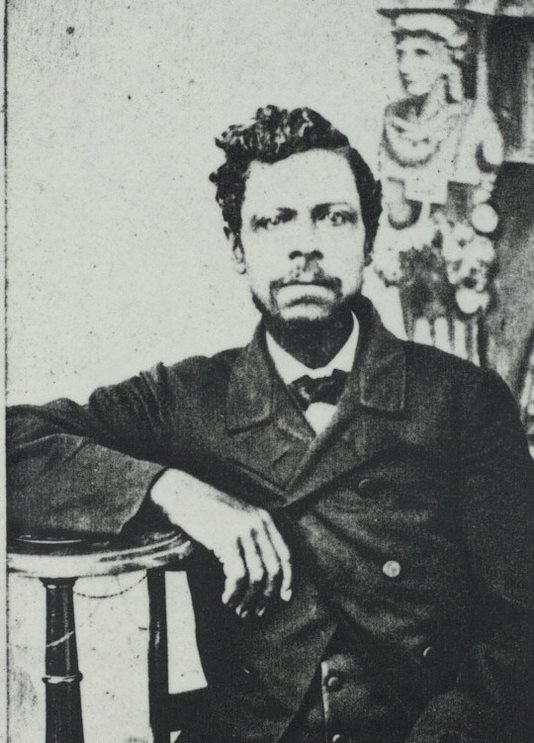

Marshall Hubert Carr (1886-1916) son. Hugh Carr and Ivy Creek Natural Area papers, MSS 10770-a Box 1, Folder 11

When Carr died in 1914, he bequeathed parts of the farm to each of his children. Their eldest daughter, Mary Louise Carr Greer became principal of the Albemarle Training School and was an influential educator in the local community. Her husband, Conly Greer, was the first African American extension agent for Albemarle County and the last family member to farm at River View Farm. After his death in 1956, Mary Carr Greer continued to live there but the land was rented to local farmers. When Mary Greer died in 1973, she left the estate to her only child, Evangeline Greer Jones, who in turn sold it. (Brickhouse)

Following its sale, the farm was slated to become a subdivision with 200 homes, but with strong support from University professors, the Nature Conservancy, and the Ivy Creek Foundation, the land was purchased jointly by the City of Charlottesville and Albemarle County in creation of the Ivy Creek Natural Area in 1978. (National Register of Historic Places Registration Form)

The history of the Carr family, their River View Farm, and the Ivy Creek Area are not only preserved but are a living memory that is thriving today. The cultural heritage of the Carr farm remains in evidence on this site. The property serves as the first stop on the Union Ridge Heritage Trail tour of African Americans, a program administered by the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center. (National Register of Historic Places)

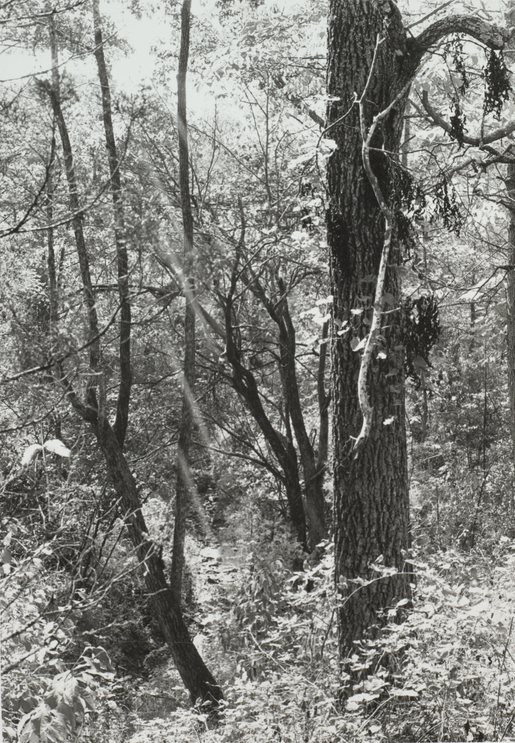

Ivy Creek Natural Area with 400 species of wildlife. Hugh Carr and Ivy Creek Natural Area papers, MSS 10770-a Box 1, Foder 11

Evangeline Greer Jones, granddaughter of Hugh Carr, wrote that she “is glad to see the farm as a home for a wide variety of wildlife, flowers and trees.” She thinks her family would be glad to see how it has turned out. A sign at the Ivy Creek Natural Area reads, “Take only pictures, leave only footprints. However, it is permissible to pick fruit from the trees in the orchard if eaten on the spot.” Jones wrote that she “is very much pleased to know that people can come and visit.” (Brickhouse)

(If you ever need to request a correction or suggest a change to a description of one of our collections, you can find the Suggestion description forms here.)

Sources:

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (contains many details about the Carr and Greer family and the River View Farm)

Brickhouse, Robert. “Nature Preserve Ex-Slave’s Legacy” The Daily Progress. September 12, 1982 (collection material)

Grohskopf, Bernice. “Legacies Nature and History at Ivy Creek: How Hugh Carr rose out of Slavery to Create the Farm that became Our Secret Garden” Albemarle Magazine. 1988 June-August.

For more information:

Flowers, Charles V. “The Creation of Ivy Creek Natural Area” Adapted from interview with Paul Saunier, Jr. The Sun, Baltimore, Maryland. April 15, 1984. (collection material)

Flowers, Charles V. “Ivy Creek is an Oasis of the Unspoiled” Interview with Dr. Benjamin Whitten. The Sun, Baltimore, Maryland. April 1984 (collection material)

Ivy Creek Foundation, Accessed 1/27/2023