On this, our last day before the library closes for the holiday, we are delighted to share a post by Regina Rush, Reference Librarian and Special Collections’ resident Christmas addict (resisting all treatment with jolly glee, we should add). Regina starts counting down to next Christmas on December 26, y’all. So, without delay, here she is!

Where does space begin? Can Mars support life? Which is better, Coke or Pepsi? Questions such as these have puzzled, befuddled, and confounded us since the dawn of humankind. But of all the mind-numbing questions in life, none shares the contemplative intensity and gravitas of the question asked by eight-year-old Virginia O’Hanlon in 1897:

“Is there a Santa Claus?”

Is the Old Jolly Elf for real, or have parents for generations been perpetrating a SERIOUS FRAUD?!

Really, she needed to know. Not even Booker T. Santa or Langston Santa would tell her. (Photo by anonymous elf.)

If truth be told, I had my doubts. That is, until one afternoon a couple of months ago, when I answered the phone at the Public Services Desk.

Let me start at the beginning. Mid-October can be a hectic time for the The Desk, as we call it. We field questions from nervous students making their first deep dive into primary research. We provide box after box to the more seasoned researchers who have made our reading room their second home and the staff their second family. Alumni show up for football games and decide to come research their time at the university in the days leading up to the game. Genealogists pop in, often on a cross-country archives crawl to learn about their family history. The Desk, to quote the immortal sage Forrest Gump, “is like a box of Chocolates, You never know what you’re gonna get.”

This particular Wednesday afternoon, the phone rang, as it often does when six things are happening at once. “Special Collections Reading Room, May I help you?” A disembodied, but not unpleasant, voice responded, “Good Afternoon, my name is …” the researcher introduced himself and launched into the purpose of his call: obtaining a copy of an item held in our large collection of American trade catalogs.

–“Is it possible to receive a copy of this item?”

–“We would need to pull the catalog and evaluate its condition. If it looks like it can withstand scanning, I will be happy to send it to you.”

I directed him to our online reference form, and asked him to send all the pertinent information necessary to identify the item. A staff member would research his query and get back in touch with him. “In fact,” I continued, “you can include my name in your query so it can be assigned to me.” The call was quickly forgotten as I turned my attention to other researchers. But the next day, when I opened the researcher’s reference request… It. Stopped. Me. Dead. In. My. Tracks. Not only had I been assigned a reference request from the Jolly Elf himself, I had actually spoken to the big man the day before.

HOLY MAKING A LIST AND CHECKING IT TWICE, BATMAN!

Old Kris Kringle himself was requesting information from one of our trade catalogs concerning a new purchase he had recently made–of what else?!– a sleigh.

See for yourself:

From R. C. at 1:02 PM on Wed Oct 11 2017

Category: Standard Reference

I would like any information on Ames Dean Sleighs.

it could be Jamie Dean out of Michigan.

I bought a Sleigh and would like to know all I can about it

Thank you for all your help.

Mr. C. aka Santa Claus

attn. Regina

Author: Small, Albert H. (Albert Harrison); Alliance Carriage Co; American Carriage Company; Ames-Dean Carriage Co; Anchor Buggy Co; Arkla Industries Inc; Barnett Carriage Co; Biddle & Smart Co; Columbia Carriage Co; Consumers Carriage and Manufacturing Co; … [more]

Format Book

Publication Date1888; 1974

Availability:Available

Special Collections Call Number TS199.A5 C2 (54 volumes)

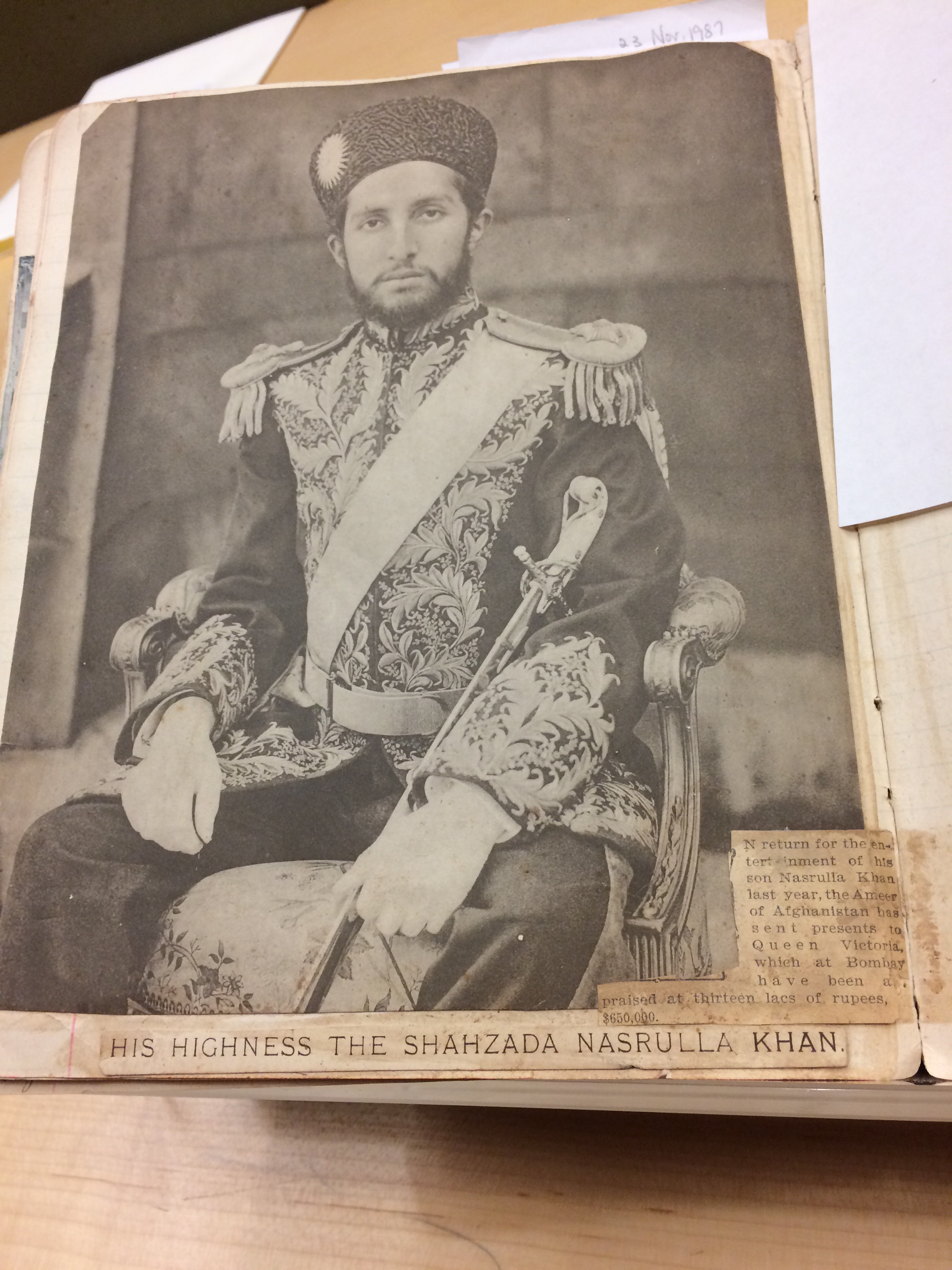

How I, of all people, had lucked into this reference request, I will never know. Needless to say, I did not disappoint. When Santa calls, I answer. I sent Santa scans from several trade catalogs from the Albert H. Small American Trade Catalogs collection. This collection boasts over 3,000 American manufacturer’s catalogs, mostly from the 19th and early 20th centuries, ranging in subject from beekeepers’ and dentists’ equipment to stationery, toilets, furniture, and yes, even sleighs! This collection is one of the many amazing gifts given by alumnus Albert H. Small, the library’s namesake and donor of the phenomenal Albert H. Small Declaration of Independence Collection.

The catalog from the Albert H. Small American Trade Catalogs collection requested by Santa. (TS199 .A5 c2 no. 3)

Images of Sleighs from the Whitney Wagon Works’ Catalogue of Carriages and Sleighs (TS 199 .A5 C2 no. 48) The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library serves researchers across the globe, including the Jolly Ole Elf from the North Pole!

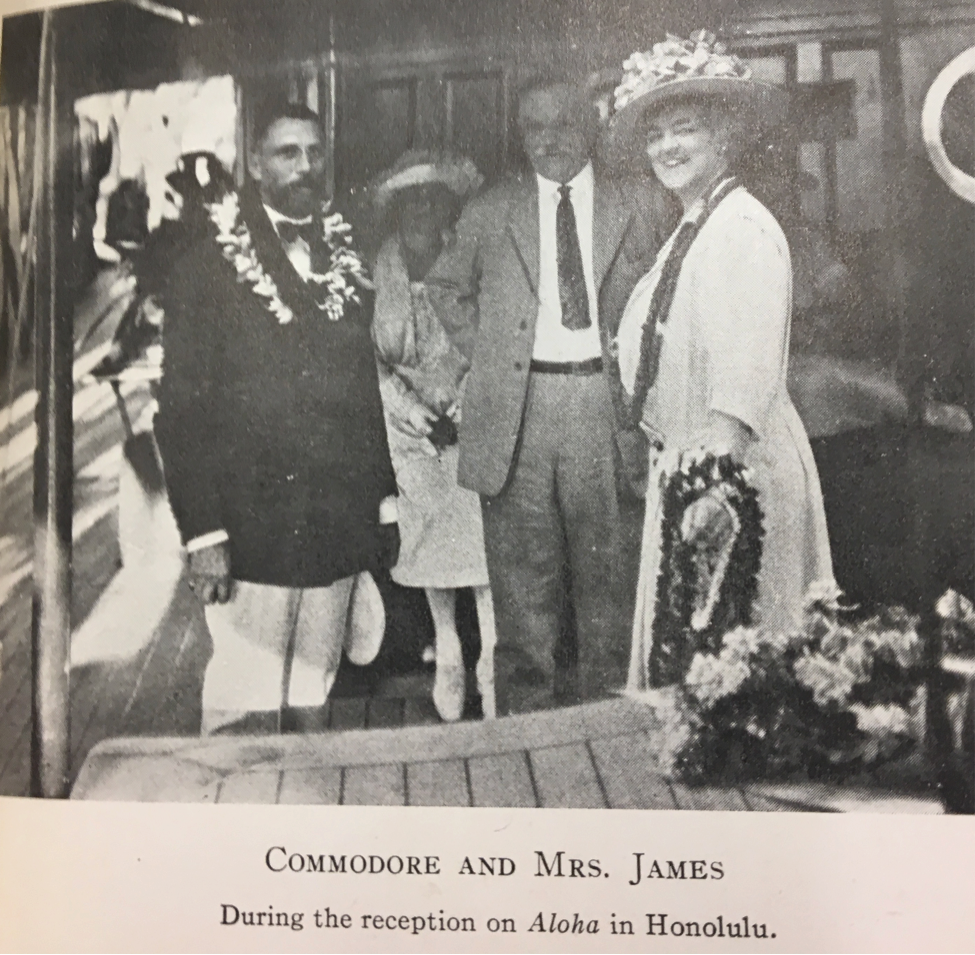

Now, for those of you concerned about violating Santa’s privacy by including his request in this blog, REST ASSURED, I obtained his permission. Sheesh! Not doing so would certainly have landed me at the top of THE Naughty List.) He even let me share his picture with you:

R.C. and L. C. aka Mr. and Mrs. Santa Claus and their little canine elf. Photo courtney Rich Clarner. For real, you guys.

As the New York Sun allayed the fears of young Virginia in 1897, I hope by sharing my story, I have helped dispel any lingering doubts of Old St. Nicks’ existence. To all the Hoos’ in Hooville who still do not believe, I can say with 100 PERCENT certainty,

Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus!

Wishing all my colleagues at the University of Virginia Library and all the loyal readers of “Notes from Under Grounds” a very safe and happy holiday!

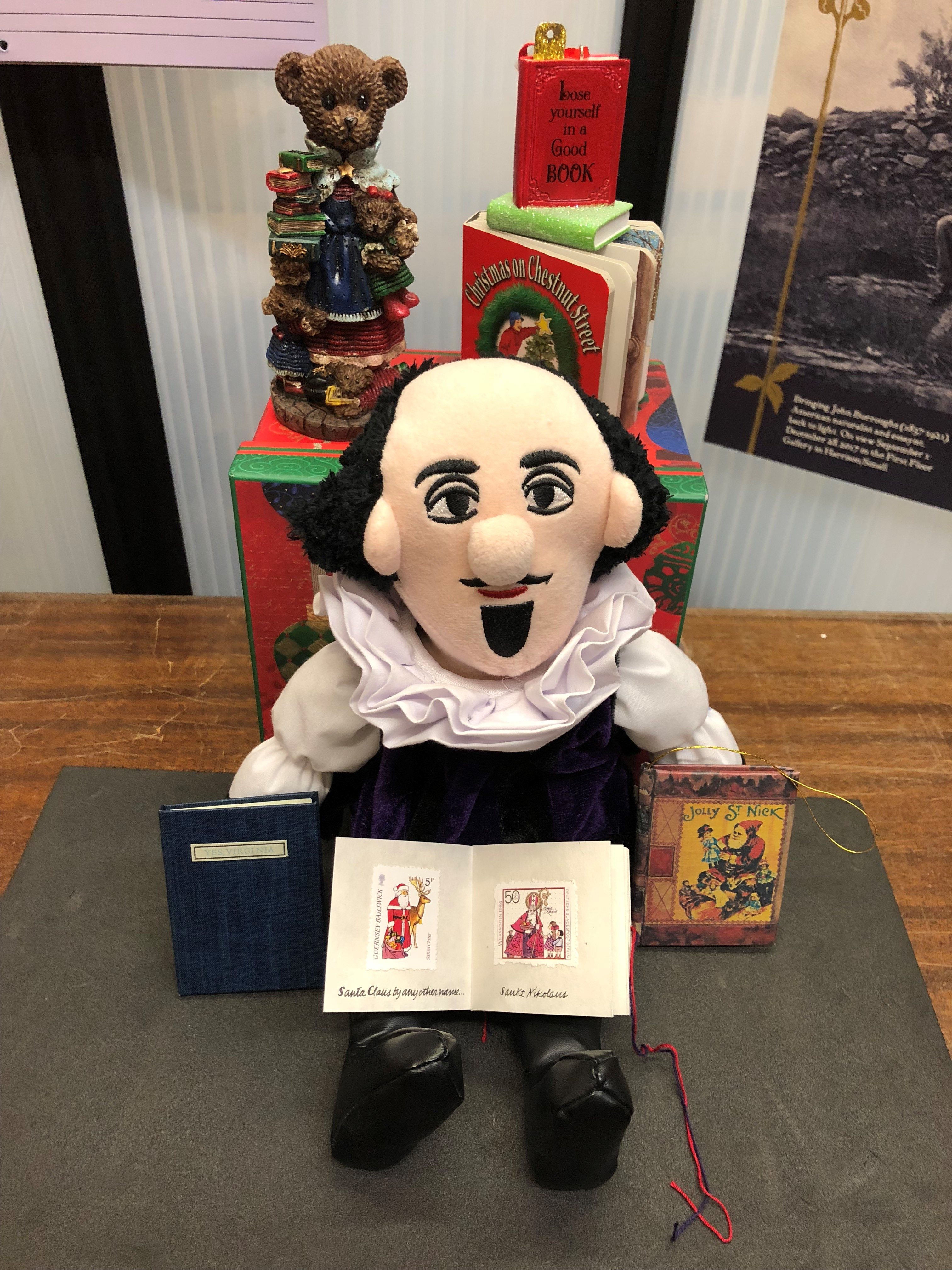

The Old Bard of Avon has been busy lately reading several books from our McGehee Miniature Book Collection. They’re just his size! Shown are Jolly St. Nick (Lindemann 05410), Yes, Virginia (Lindemann 3004), and Santa Claus By Another Name (Lindemann 6589). All other items pictured are courtesy Regina Rush. (Apologies to Will Shakespeare, we forgot to make him a Santa hat!).