Recount, O Muse, the editors who fell during the epic battle for Shakespeare’s words three centuries ago. Pope, that poetic genius, was blinded by Shakespeare’s meter; Theobald, may he rest in peace with his dictionaries, died of dulness; Johnson, the father of our language, was cut to the core by the Bard’s vulgar words; and Malone, the lone Irishman, lost his ear. In this, the battle of Shakespeare editions, each editor thought he was victorious. But alas! they all cried “huzzah!” too soon, for each editor soon felt the perfectly timed twist of the rhetorical knife or the slap of a rhetorical glove.

In all seriousness, over the course of the eighteenth century, editors battled with each other over the words of Shakespeare. The complicated work of editing Shakespeare began in earnest, arising from both the Enlightenment spirit of scholarship and a growing recognition of Shakespeare’s importance. Each editor sought to claim the “true” Shakespeare. Yet before the days of the First Folio’s renown (which Samuel Johnson first suggested editors use in 1765), editors typically used their predecessor’s editions as their base texts. They did not start with early folios or quartos, which were difficult to locate. For various reasons, each editor asserted the rightness of his own edition of Shakespeare, and as a result, each edition was met by equally strong criticism. Perfecting the noble art of the insult, editors padded their own editions with criticisms of their predecessors. In a few cases, they were so fired up they wrote entire books dedicated to explaining how their predecessors were wrong.

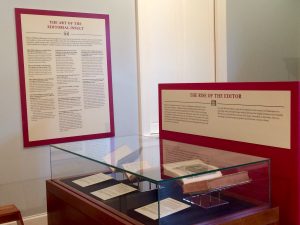

Our current exhibition, Shakespeare by the Book, has an entire section entitled “We Quarrel in Print: Editing Shakespeare.” Alongside books, it features a listicle of our favorite editorial insults from the eighteenth century, mined from the footnotes and the books in the exhibition. Read on to see the list in its entirety!

Editor William Warburton on Nicholas Rowe’s 1709 edition of Shakespeare (1747):

A Wit indeed he was; but so utterly unacquainted with the Business of Criticism, that he did not even collate or consult the first Editions of the Work he undertook to publish; but contented himself with giving us a meagre Account of the Author’s Life, interlarded with some common-place Scraps from his Writings.

Editor Lewis Theobald on Alexander Pope’s 1725 editing of a passage in Hamlet (1726):

[N]o Body shall perswade me that Mr. Pope could be awake, and with his Eyes open, and revising a Book, which was to be publish’d under his Name, yet let an Error, like the following, escape his Observation and Correction.

Lewis Theobald’s Shakespeare Restored is a book entirely dedicated to criticizing Pope’s edition of Shakespeare.

Editor William Warburton on Lewis Theobald’s 1733 edition of Shakespeare (1747):

Mr. Theobald was naturally turned to Industry and Labour. What he read he could transcribe: but, as what he thought, if ever he did think, he could but ill express, so he read on; and by that means got a Character of Learning, without risquing, to every Observer, the Imputation of wanting a better Talent.

Editor William Warburton on Lewis Theobald’s 1733 edition of Shakespeare (1747):

Mr. Theobald was naturally turned to Industry and Labour. What he read he could transcribe: but, as what he thought, if ever he did think, he could but ill express, so he read on; and by that means got a Character of Learning, without risquing, to every Observer, the Imputation of wanting a better Talent.

Critic Thomas Edwards in a satirical “supplement” to William Warburton’s 1747 edition of Shakespeare (1748):

Poor Shakespear! your anomalies will do you no service, when once you go beyond Mr. Warburton’s apprehension; and you will find a profess’d critic is a terrible adversary, when he is thoroughly provoked: you must then speak by the card, or equivocation will undo you. How happy is it that Mr. Warburton was either not so attentive, or not so angry, when he read those lines in Hamlet,

Give me that Man

That is not passion’s slave, and I will wear him

In my heart’s core; aye, in my heart of heart—

We should have then perhaps heard, that this was a way of speaking, that would have rather become an apple than a prince.

Alexander Pope satirizing the voice of Lewis Theobald in The Dunciad, who pays homage to the goddess Dulness with his edition of Shakespeare (1728):

Here studious I unlucky Moderns save,

Nor sleeps one error in its father’s grave,

Old puns restore, lost blunders nicely seek,

And crucify poor Shakespear once a week.

For thee I dim these eyes, and stuff this head,

With all such reading as was never read;

For thee supplying, in the worst of days,

Notes to dull books, and Prologues to dull plays;

For thee explain a thing ‘till all men doubt it,

And write about it, Goddess, and about it.

Samuel Johnson first on Alexander Pope’s 1725 edition of Shakespeare…

This was a work which Pope seems to have thought unworthy of his abilities, being not able to suppress his contempt of the dull duty of an editor. He understood but half his undertaking.

…and then on Lewis Theobald’s 1733 edition (1765):

Pope was succeeded by Theobald, a man of narrow comprehension and small acquisitions, with no native and intrinsick splendour of genius, with little of the artificial light of learning.

Critic William Kenrick on a footnote in Samuel Johnson’s 1765 edition of Shakespeare (1765):

Had our editor nothing to offer better than this? And hath he so little veneration for Shakespeare, as so readily to countenance the charge against him of writing nonsense? Did you, Dr. Johnson, ever read the scene, wherein this passage occurs, quite through?

Critic Joseph Ritson on Edmund Malone’s 1790 edition of Shakespeare (1792):

But it is not the want of ear and judgement only of which I have to accuse Mr. Malone: he stands charged with divers other high crimes and misdemeanors against the divine majesty of our sovereign lord of drama; with deforming his text, and degrading his margin, by intentional corruption, flagrant misrepresentation, malignant hypercriticism, and unexampled scurrility. These charges shall be proved—not, as Mr. Malone proves things, by groundless opinion and confident assertion, but—by fact, argument and demonstration. How sayest thou, culprit? Guilty or not guilty?

Critic John Collins accusing George Steevens of bribing the printers to show him proof sheets so he could plagiarize Edward Capell’s 1768 edition of Shakespeare (1779):

You will then find, my Lord, a regular system of plagiarism, upon a settl’d plan pervading those later editions throughout, and that,—not [Doctor Johnson’s] former publication, as one would naturally suppose, but—Mr. Capell’s, in ten volumes, 1768, is made the ground-work for what is to pass for the genuine production of these combin’d editors, and is usher’d to the world upon the credit of their names…But I cannot help observing, —that such injustice, as requir’d the united efforts of effrontery and falsehood to conceal it, amounts to a full acknowledgement of the superior worth of the person injur’d, and is an undeniable argument of as much indigence on the one hand as of abundance on the other.”

Editor Thomas Caldecott on the whole lot of his predecessors, in a review of Thomas Bowdler’s Family Shakespeare (1822):

In spite of the national veneration universally felt for our great bard, he has been subjected, amongst us, to a series of more cruel mutilations and operations than any other author who has served to instruct or amuse his posterity. Emendations, curtailments, and corrections (all for his own good) have been multiplied to infinity, by the zeal and care of those who have been suffered to take him in hand. They have purged and castrated him, and tattoed and be-plaistered him, and cauterized and phlebotomized him, with all the studied refinement, that the utmost skill of critical barbarity could suggest. Here ran Johnson’s dagger through, “see what a rent envious Pope has made,” and “here the well-beloved Bowdler stabbed:” while, after every blow, they pause for a time and with tiresome diligence unfold the cause why they that did love him while they struck him, have thus proceeded.

If you would like to see more editors behaving badly, come see Shakespeare by the Book in person. The exhibition runs through December 29th, 2016, with the Folger Shakespeare’s Library’s First Folio making its appearance for the month of October.