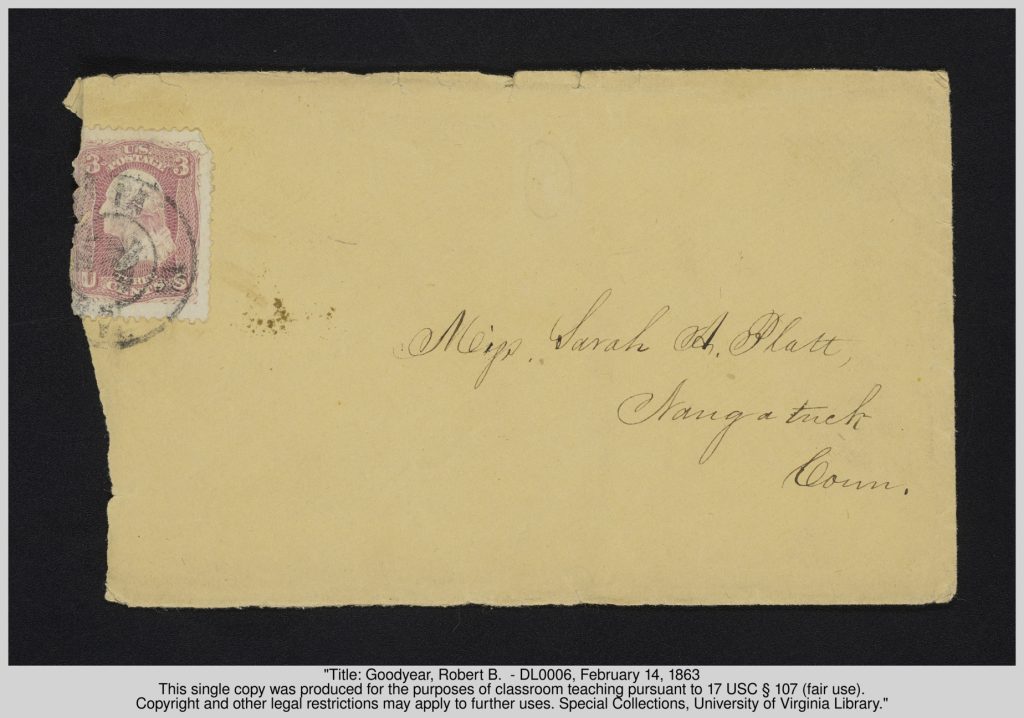

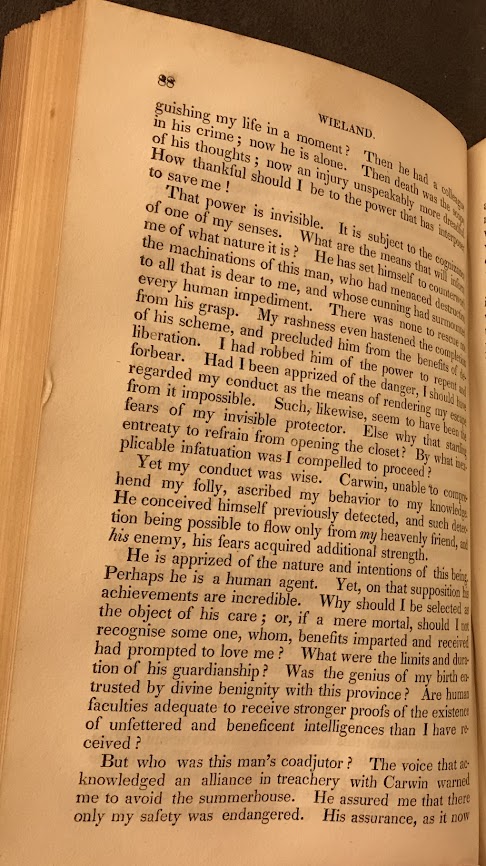

July is Disability Pride Month. This post is contributed by Ellen Welch, Manuscripts and Archives processor. Ellen recently processed a letter, MSS 16844, typed and signed by Helen Keller.

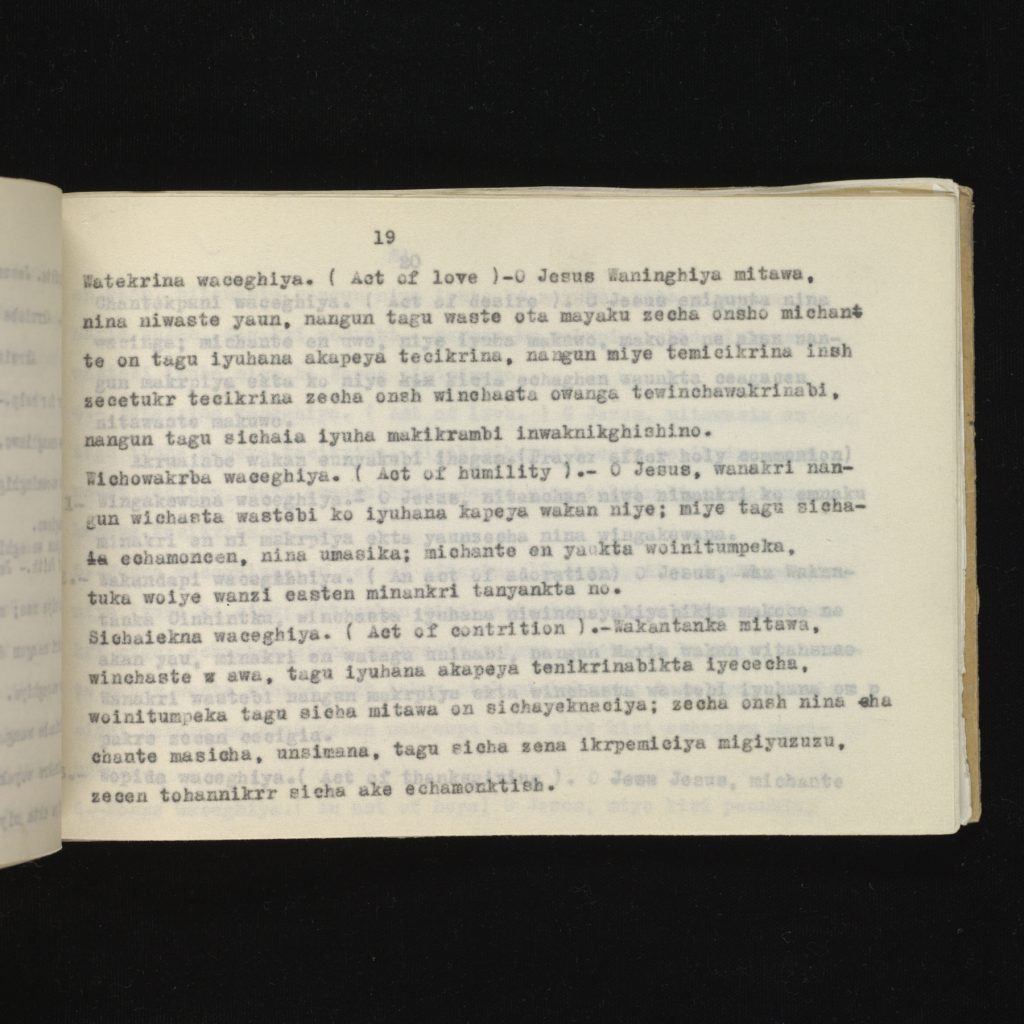

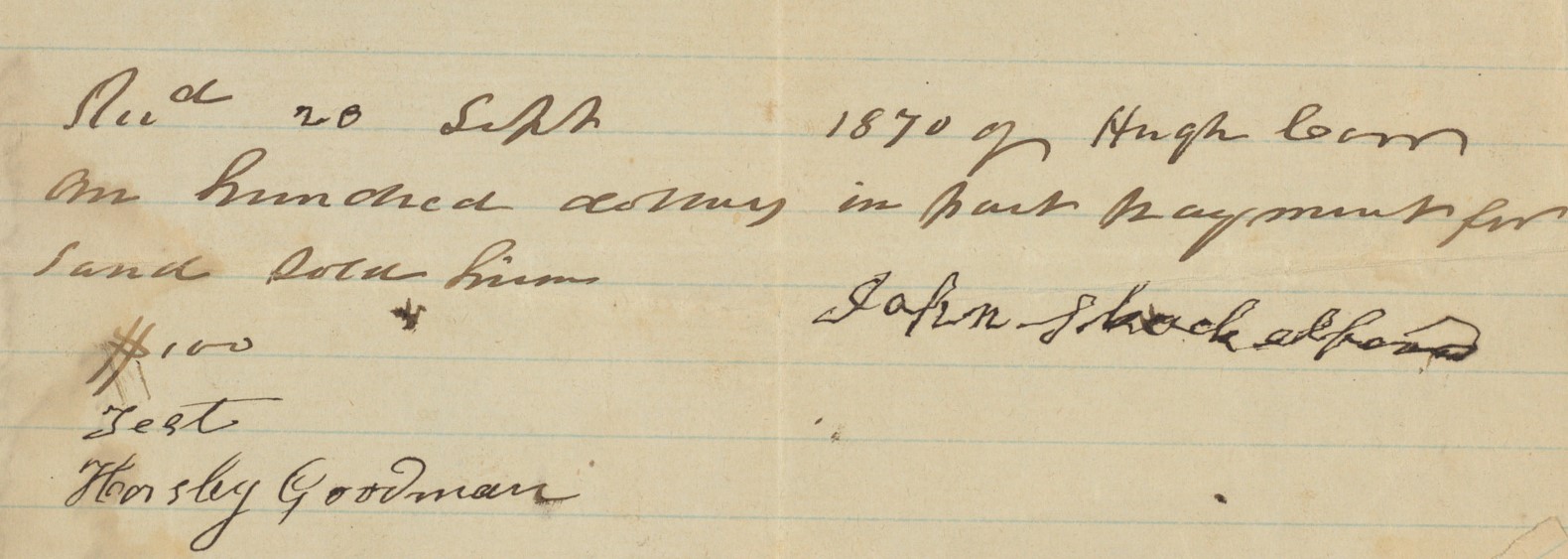

MSS 16844, Letter written by Helen Keller. November 25, 1944.

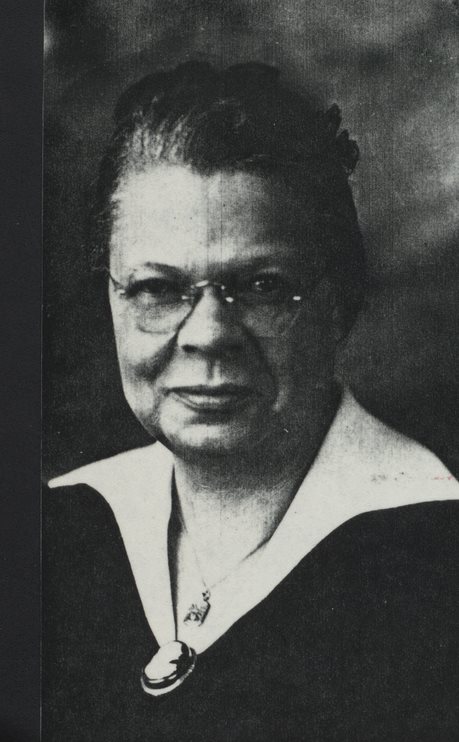

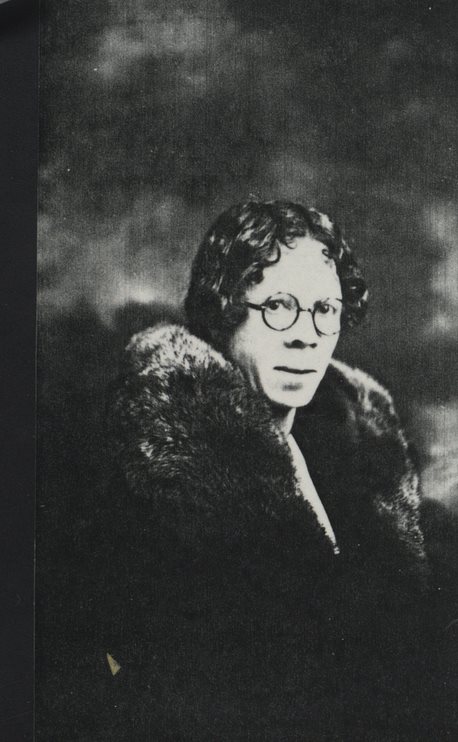

Helen Keller (1880-1968) was an influential twentieth century author, activist, educator, and humanitarian. Born in Tuscumbia, Alabama, she lost the ability to see and hear due to an illness that she contracted before she was two years old. Throughout her life, Keller advocated for people with disabilities, labor rights, and women’s suffrage, and co-founded the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in 1920.

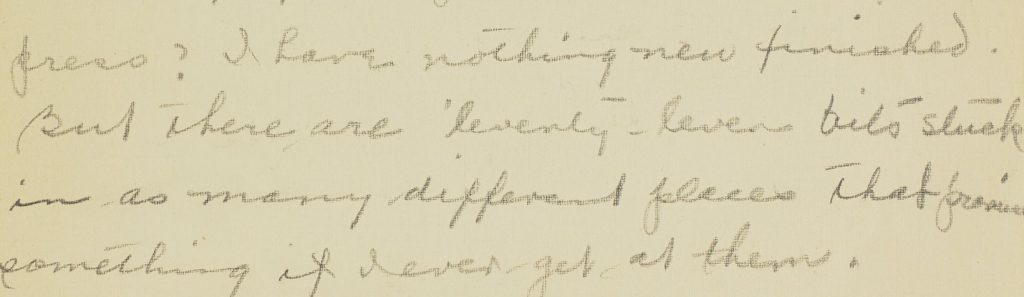

The letter written by Keller that Special Collections holds is dated November 25, 1944, and contains an appeal for funds for the American Foundation for the Blind, where she worked for twenty years. The letter is intriguing–particularly when you consider that Keller had to develop the skills to type without the ability to see the keys on the typewriter. The bottom of the typed letter also bears Keller’s handwritten signature.

Helen Keller using a typewriter at Radcliffe College, 1900.

My curiosity about how Keller would have been able to type the letter led me to research how that was possible. In 1892, Frank H. Hall, superintendent of the Illinois School for the Blind, invented the Hall Braille Writer. According to Erik Larson in his 2004 book A Devil in the White City, during the 1893 Chicago World Fair Keller approached Hall, hugged, and kissed him, thanking him for his invention. Keller would have been about twelve or thirteen at the time. She was taught to use the Hall Braille Writer by her teacher, Anne Sullivan (1866-1936). Sullivan held Keller’s finger to every key and hand spelled the letter of the alphabet that the braille key represented. This was slow work and required a great deal of memorization. With practice, Keller was able to type. No one typed for her. Through assistive technology, Keller had the ability to type independently.

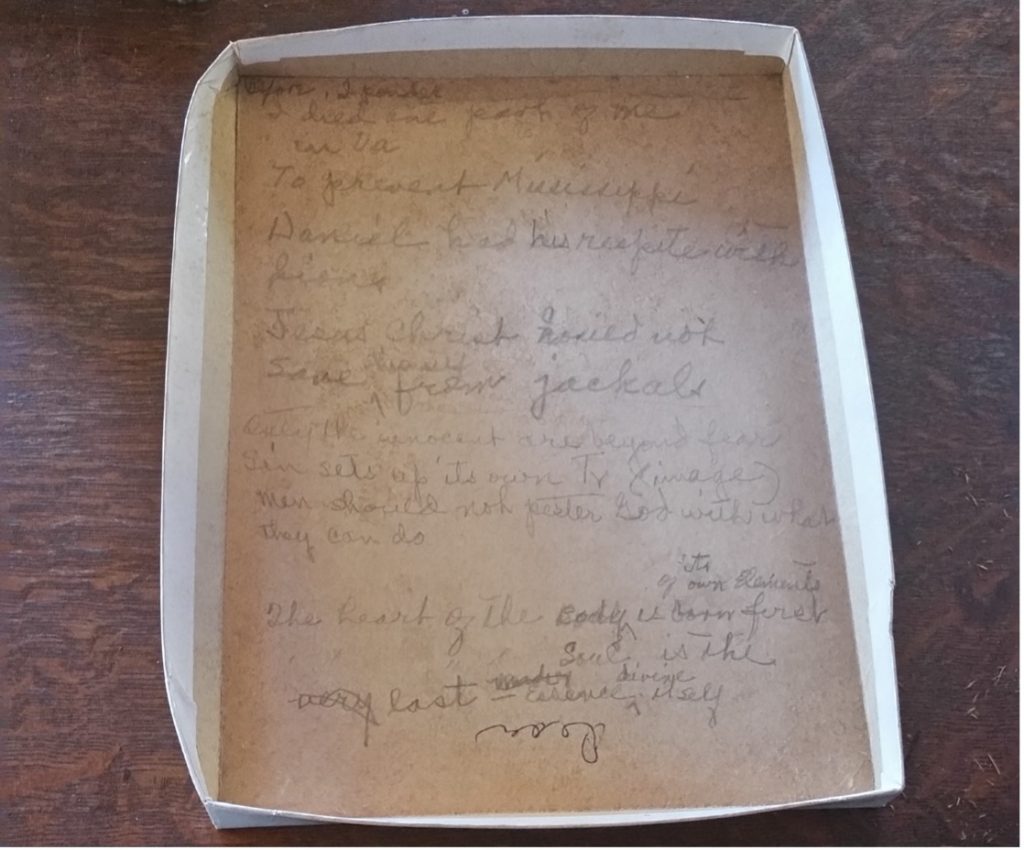

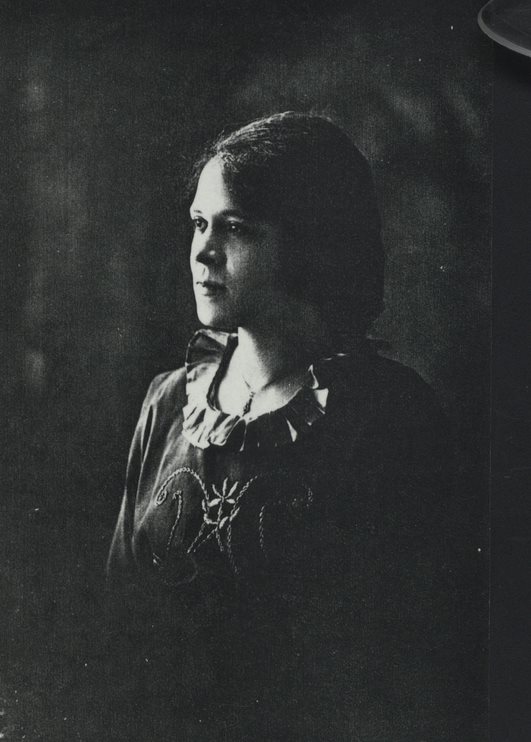

As seen on MSS 16844, Keller could also write by hand. Her handwriting is legible and consistently upright like the writing in calligraphy. The neat handwriting of someone who could not see what they were writing seemed unusual to me. Upon viewing Keller’s letter, my first thought was that someone else typed it for her and she signed her name at the bottom. As a person without a visual disability, I assumed it would be impossible for a person who is blind to use a typewriter. I was previously unaware of the challenges that a blind person must overcome in typing and writing. Processing this letter allowed me to confront a bias I was unaware of and revealed the challenges a person with disabilities might encounter and overcome.

I learned that it bears this specific style because of the use of an assistive writing board and a method called square-hand. People with visual disabilities would place a piece of paper on the writing board, which had horizontal grooves on it. The paper would press into the grooves, creating lines that could be felt as a person’s hand moved across the page, keeping their writing straight. As they wrote along the grooves, with their left index finger they would cover the letter they had written with their right hand, preventing the letters from overlapping. They would often use a finger’s width to create spaces between the words they wrote. Writing within the grooves gave letters a square appearance, which is where the term square-hand comes from.

A nineteenth century writing board used at the Perkins School for the Blind. (2)

A letter that Keller wrote when she was nine years old. Notice the tiny wiggle at the beginning of the drops of the letters “y,” “g” and “p,” showing the indent of the writing board. (1)

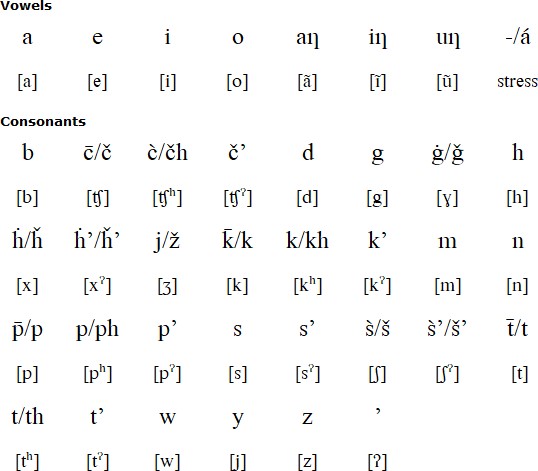

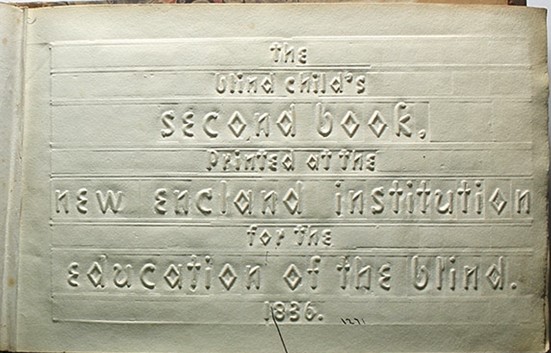

In the nineteenth century, there were many different tactile reading and writing systems for people with visual disabilities, including Embossed Roman letters, Boston line letter, New York Point, and French, English, and American braille. The origin of braille came about during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) when, in 1815, a French artillery captain named Charles Barbier de la Serre (1767-1841) developed a tactile code using raised dots for soldiers to use to silently communicate in the dark. This system came to be known as night writing. The National Institute for Blind Youth in Paris (est. 1785) adopted night writing to teach their students. In 1824, a fifteen-year-old student at the school named Louis Braille (1809-1852) modified Barbier’s night writing code, making it more legible for people with visual disabilities. Barbier’s code adapted phonetic sounds, whereas Braille’s interpreted letters of the alphabet, included numbers and punctuation, and was more compact and easier to quickly interpret. Braille’s improved method bears his name, braille. By 1916, it was the dominant tactile reading method. At present, there are over one hundred and thirty-three braille codes for different languages.

The title page of a book printed in Boston line letter, published in 1836 by what is now the Perkins School for the Blind. (2)

Sample page from Procedure for Writing Words, Music, and Plainsong in Dots, by Louis Braille, 1829. (2)

While braille has prevailed as the tactile reading method, other methods were also being developed in the nineteenth century. There was inconsistency and controversy among the various schools for the blind between maintaining the use of New York Point or moving to braille. This became known as “The War of the Dots,” which lasted in the United States for nearly eighty years. Caught in the middle of the debate, people with visual disabilities had to learn as many as five or six different tactile reading methods. When they gained literacy in one, it wasn’t unusual for them to discover that the books they wanted access to were exclusively printed in another format. (3) New York Point was often recommended by instructors without visual disabilities because it was more accessible for them. However, by 1854 braille prevailed with the help of educators and advocates with visual disabilities.

Keller was distraught that she had to learn multiple tactile codes to access reading material. In 1909, she advocated for the adoption of braille. By 1932, all English-speaking countries used it because of its improved accessibility. Almost two-hundred years after Braille proposed his method, braille is used worldwide in over one hundred and thirty languages. While people with deaf blindness, like Keller, still rely on methods like braille for access to materials, in the late-twentieth and now into the twenty-first century, people with visual disabilities also have access to audio text, voice-recognition software, artificial intelligence, and other technologies. (3) From writing boards, line types, and braille to assistive developments for the typewriter, audio text and artificial intelligence, technology over the past two-hundred years has increased inclusion, equity, and access for people with disabilities.

Through processing this letter typed and signed by Helen Keller, I have become aware of the many ways that people with disabilities have had to interact with the world around them throughout history. The determination and strength they have shown in developing, learning, and advocating for inclusive technologies is incredible. In a world that often overlooks or takes for granted the challenges they face; it is important to recognize them and their accomplishments. The presence of Keller’s letter in our collection serves as a reminder of her achievements and is an inspiration for us all.

For more information about Helen Keller:

- Keller, Helen. Midstream: My Later Life. Garden City: Doubleday, Doran & Co. Inc., 1929. https://archive.org/details/midstreammylater017614mbp/page/n7/mode/2up.

- Keller, Helen. “Optimism.” New York: T. Y. Crowell and Company, https://archive.org/details/optimismessay00kelliala/page/n7/mode/2up.

- Keller, Helen. The Story of My Life. New York: Signet Classics, 2010.

- Keller, Helen. The World I Live In. New York: New York Review Books, 2003. https://archive.org/details/worldilivein0000kell/mode/2up.

Sources:

- Riener, Mimzy, “How Did Helen Keller Navigate her World,” Late Night Writing Advice Blog. https://mimzy-writing-online.tumblr.com/post/683836657798152192/how-did-helen-keller-navigate-her-world.

- McGinnity, B.L., Seymour-Ford, J. and Andries, K.J. (2004) Reading and Writing. Perkins History Museum, Perkins School for the Blind, Watertown, MA. https://www.perkins.org/archives/historic-curriculum/reading-and-writing/

- Letizia, Nelle, “History of tactile print systems explored in new Vancouver exhibit”, Washington State University Library, 29 May 2024. https://news.wsu.edu/news/2024/05/29/history-of-tactile-print-systems-explored-in-new-vancouver-exhibit/