This week, we are pleased to feature a guest post from Anne Causey, Public Services Assistant for the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

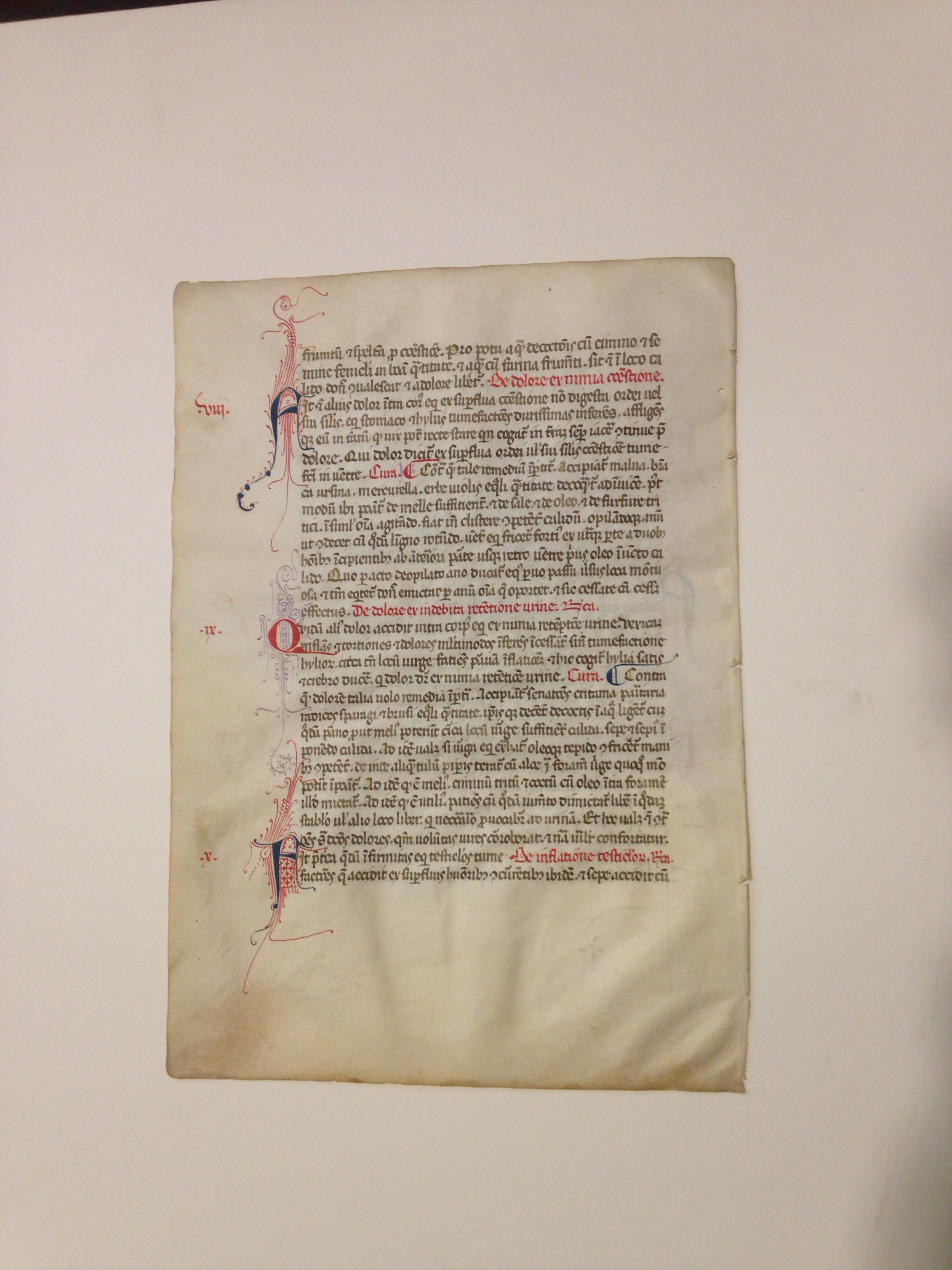

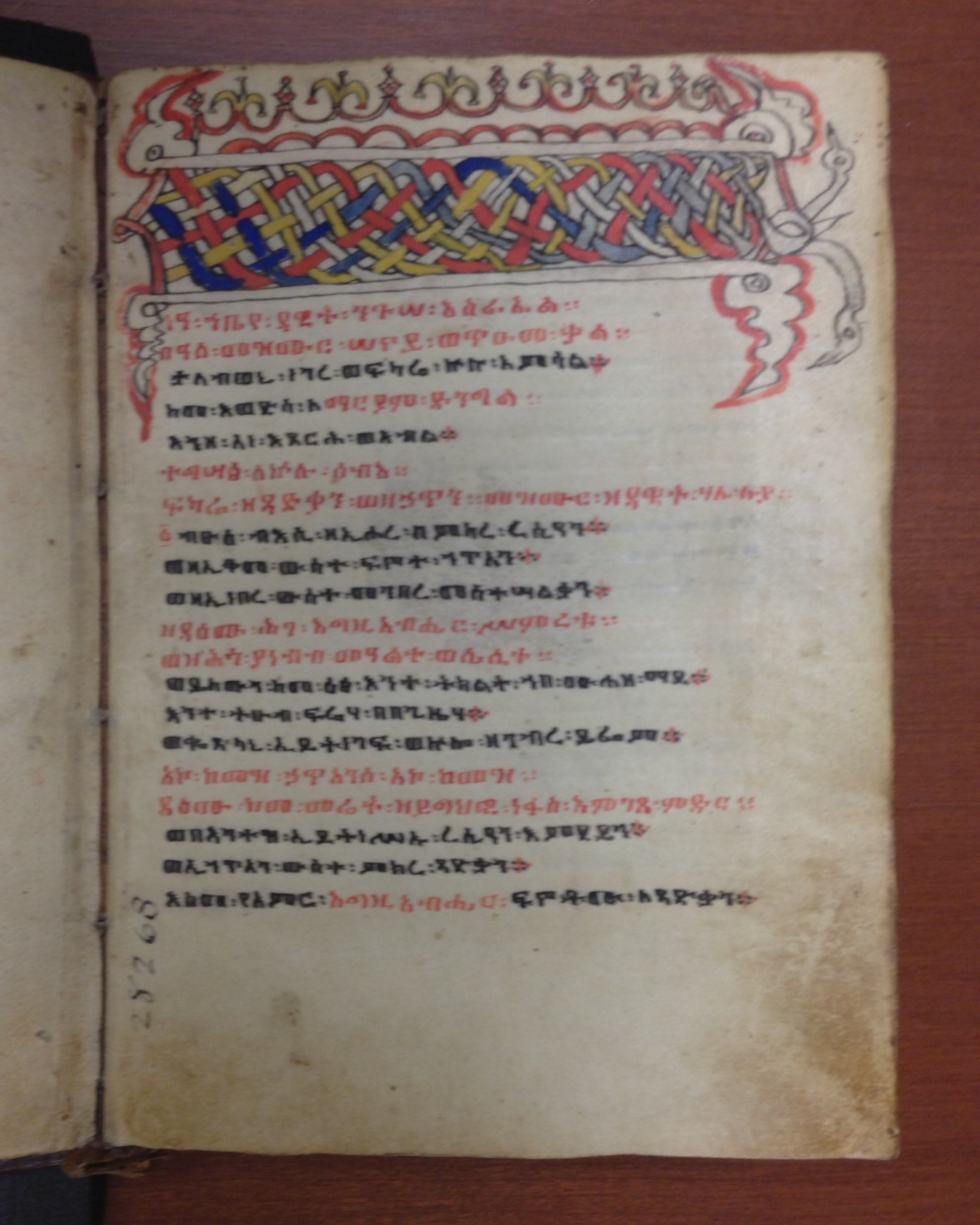

When I joined the Small Special Collections Library eight years ago, I realized how much I loved medieval manuscripts: books from before the emergence of printing (ca. 1450), which are often artfully decorated in vibrant natural colors, and sometimes gold leaf. Mostly I loved them because they are so beautiful (and so old), and amazingly enough, all done by hand!

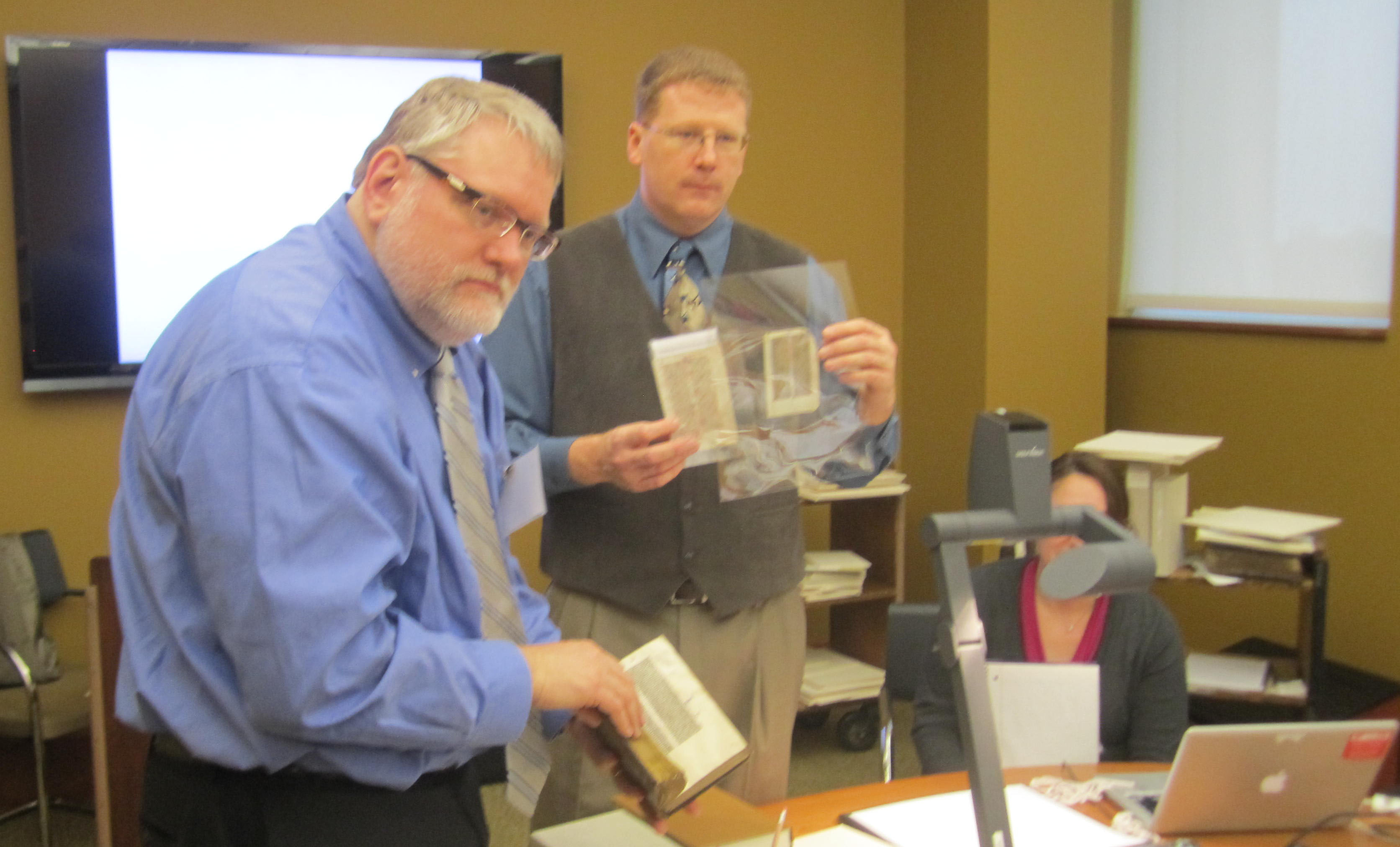

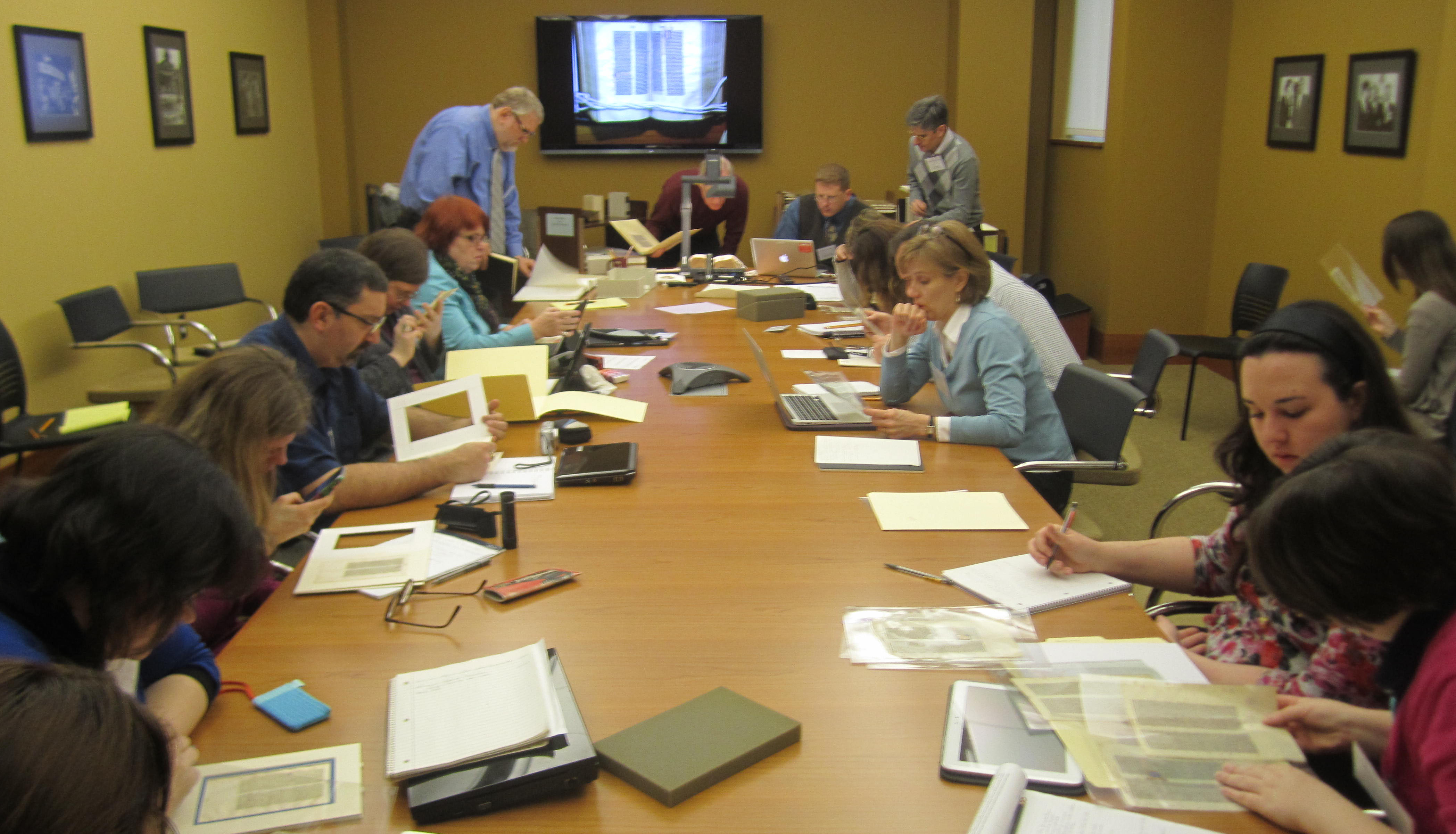

I am always searching for opportunities to learn more about these gems, so in March I attended “Understanding Medieval Manuscripts,” a two-day seminar at the University of South Carolina. The class was hosted by USC and Scott Gwara, USC professor of English and comparative literature, along with guest lecturer Professor Eric J. Johnson, curator of early books and manuscripts at the Ohio State University, who brought along 8 codices (books) and 40 fragments from his institution for study. In the class, I discovered that beyond the beauty of these illuminated books, there is much to learn–even from a single page of text.

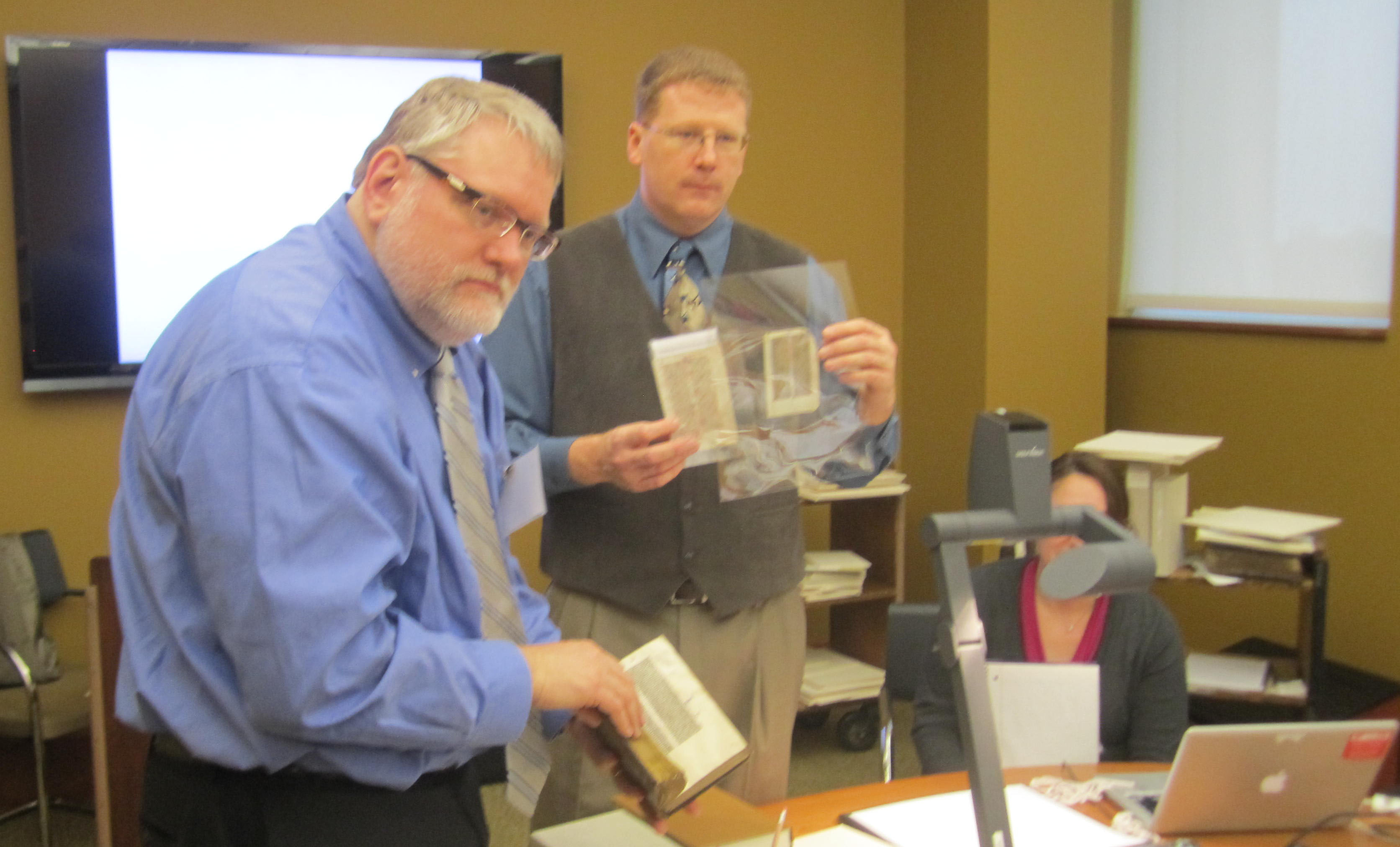

Professors Scott Gwara and Eric Johnson show fragments of medieval manuscripts to the class. (Photograph by Anne Causey)

The Basics

Professor Johnson started us off with a discussion of parchment. Parchment (or, “vellum”) is treated animal skin, and was the dominant surface for writing from the fourth century C. E. to the fourteenth century C. E.

Making parchment was a planned process – “not an afterthought,” he said. It could take eight to 16 weeks. One has to kill the animal, drain the blood, soak it in water and lime; set the skin on a herse (frame) and with a curved blade and gloves strip away the flesh side and “pull off as much hair and gunk as possible.” The uneven sheet that is left can be cut into regular pieces

You’ll see lots of imperfections in the skin, Johnson pointed out. The hair and flesh side are easy to distinguish: the hair side has lots of follicles and is rougher. There may be sewing holes that were elongated and repaired on the herse, or round holes that came from a wound or insect bite. “The saggy bits,” such as the neck, shoulders and belly, become translucent and are sometimes wrinkled.

You can determine man-made damage such as cuts and scrapes, or ink that burned through from the letters, or there may be elemental damage – extreme temperatures can cause parchment to be brittle and brown.

There are other things to look for as well. What kind of quill did the scribe use – small bird or large? What is the pricking and ruling like? What kind of ink ? Was it lampblack (not as good for parchment) or was it oak gall mixed with sap? Are visible differences due to a change in the ink or the introduction of a different scribe? Are there scribal errors and corrections – eye skip errors, erasures, insertions?

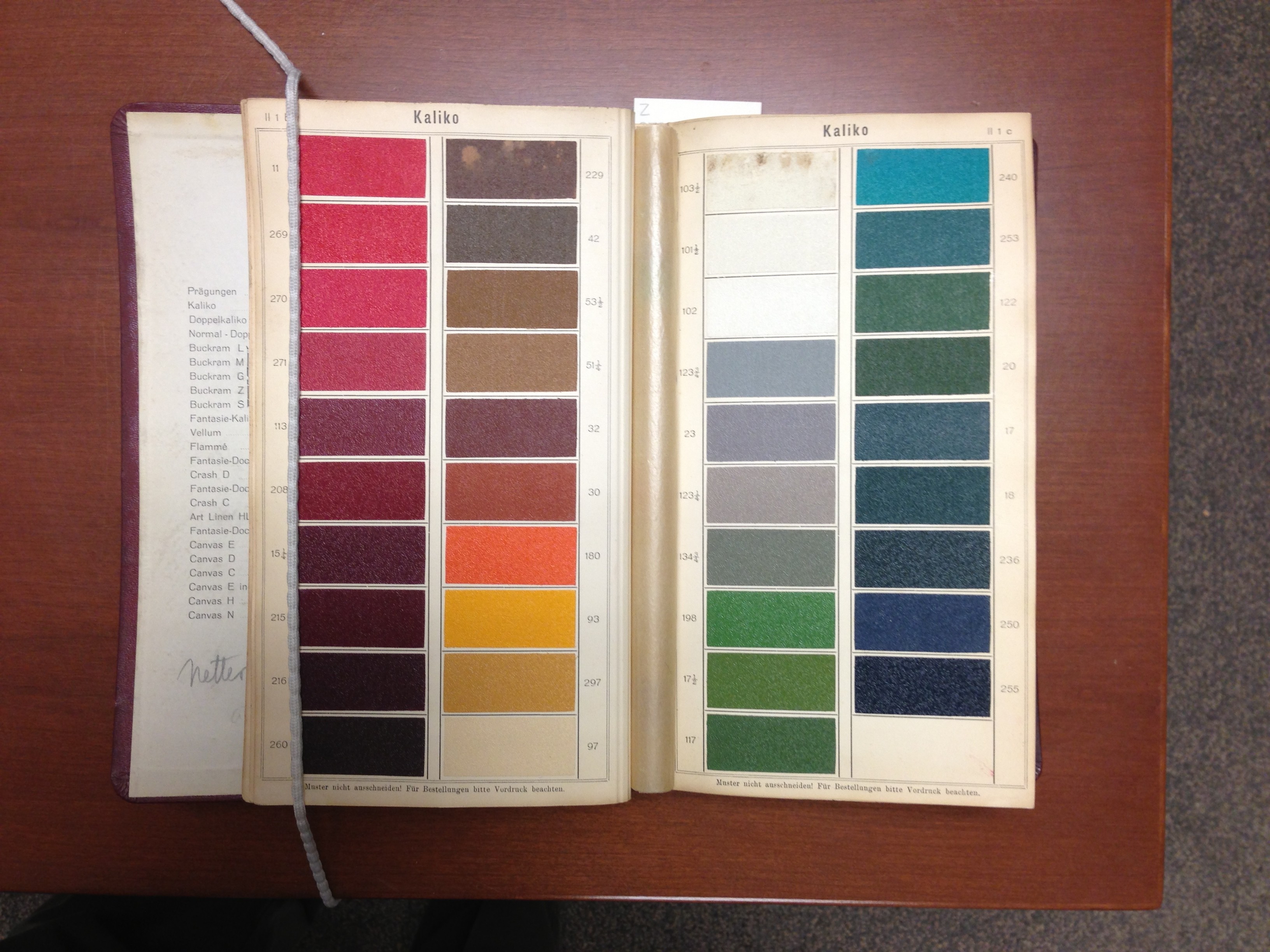

“This is text under the text – every last bit of manuscript has gone through a craft process,” Johnson said. By studying a manuscript’s physical characteristics and comparing it to other examples, we learned, you can determine how and when it was produced. He suggested that when teaching to undergraduates, you might even pair fragments with incunables (the earliest printed books, from about 1450 to 1501) as well as books from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

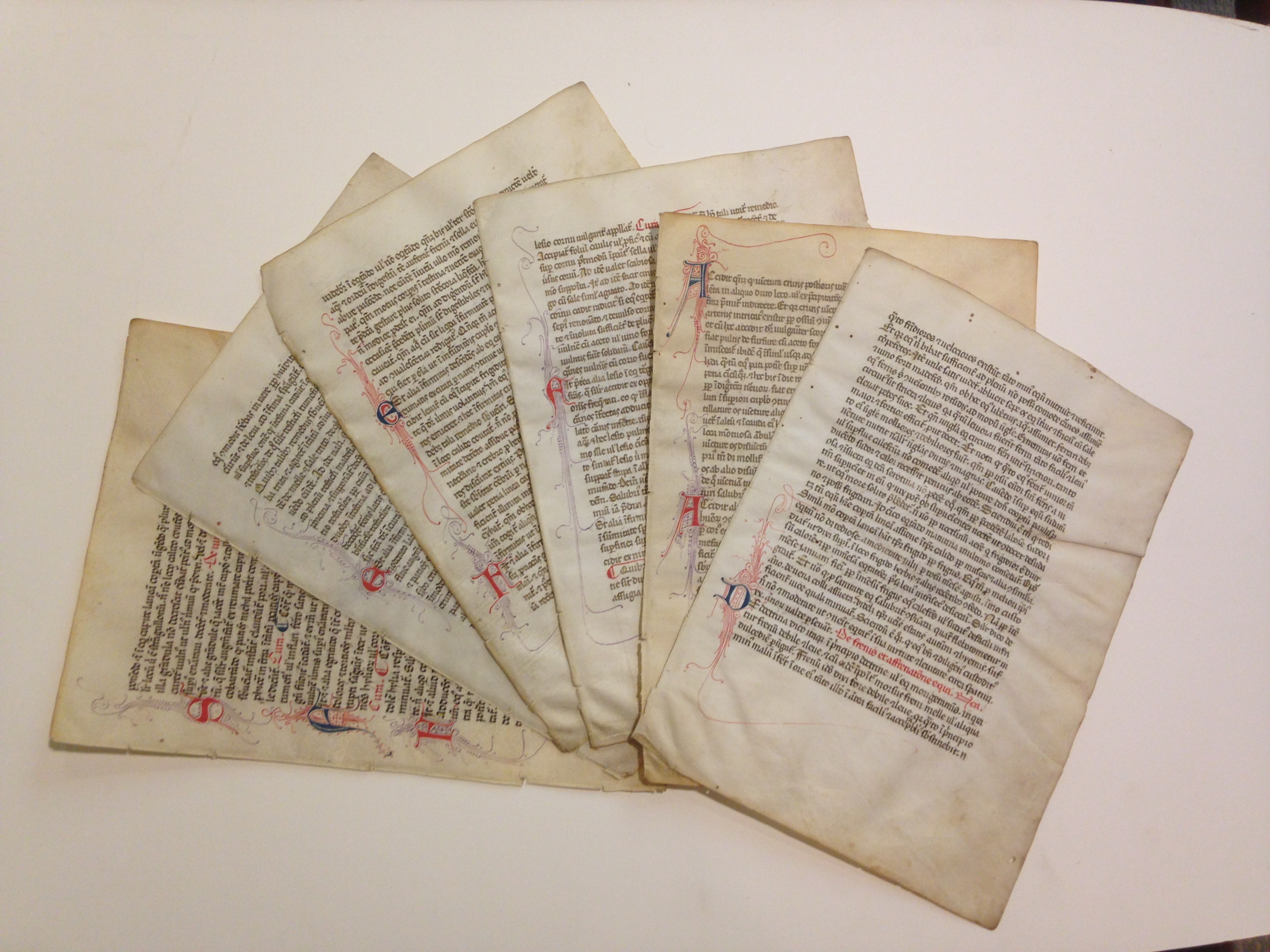

The Unexpected Beauty of Fragments

In the class, we discussed and reviewed Bibles, books of hours, breviaries and psalters. We had ample time for hands-on examination, which we did in pairs. Surprisingly, the category Eric Johnson is most excited about? Fragments! And not even the “prettiest” fragments at that.

The dirtier they are, the better – it means they have been used a lot and they have a lot to say—undergrads have a huge opportunity to access them.

Look at your manuscripts – fragments with many hands [multiple scribes] and imperfections. They are really great places to learn. You can pass them around and give students a chance for the tactile experience.

Professor Johnson talks to the class about a fragment of a medieval manuscript.

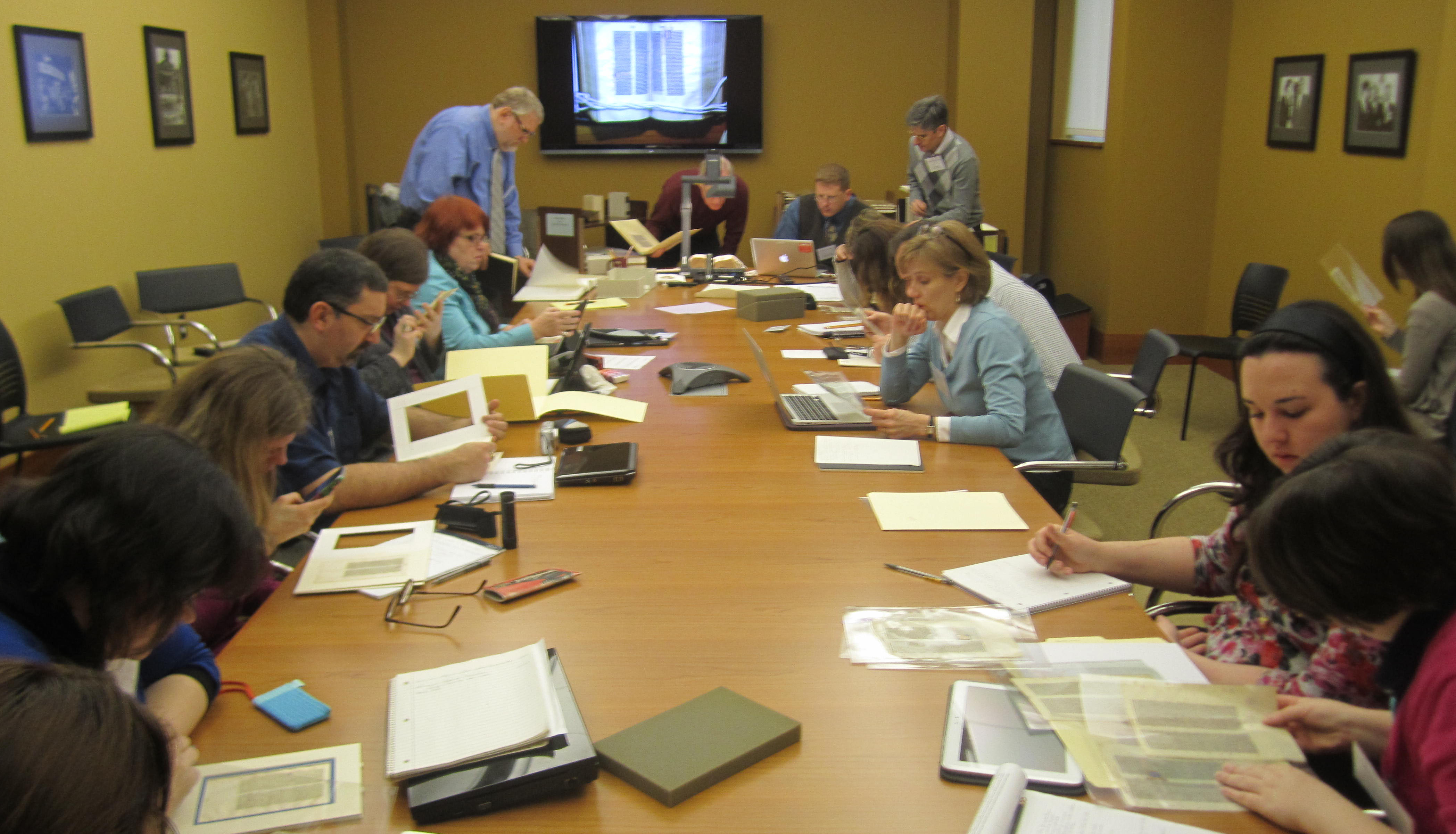

Students from South Carolina, North Carolina, New York, Michigan, and Virginia study fragments of medieval manuscripts during class. (Photograph by Anne Causey)

Sometimes fragments come about because someone has broken apart a medieval manuscript. Breaking books is a problem for many reasons – including the fact that pages lose their context. People often want the decorated pieces to frame as artwork and don’t care about the text or meaning. However, the undecorated fragments have much to say to us, Johnson said:

Studying them is not so much about coming up with the right answer but coming up with answers to help us interact with a book.

Returning Home, Energized!

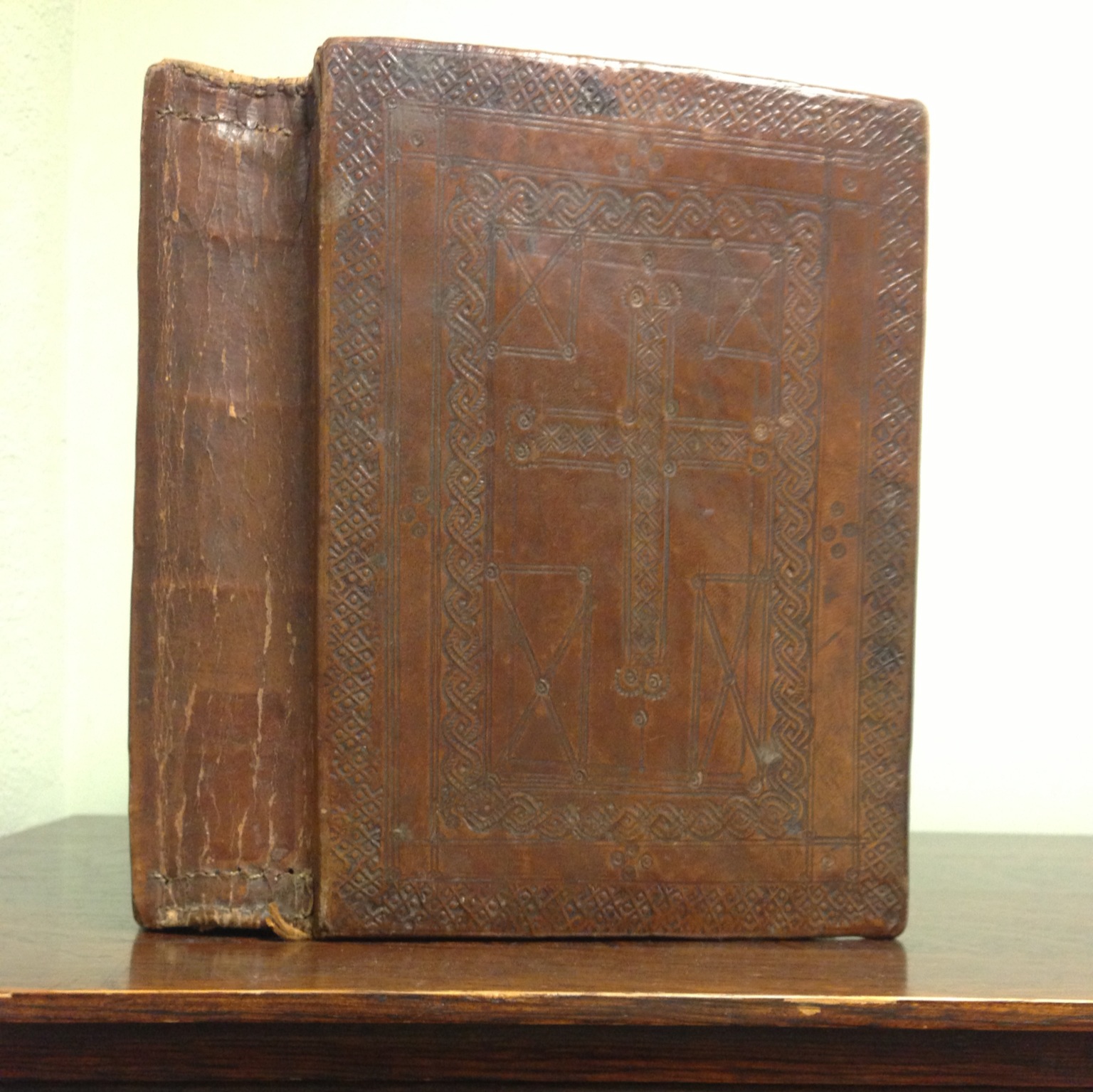

Afterward the course ended, I wanted to rush back to the Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library and immediately begin examining our fragments! Besides our thirty more-or-less complete medieval manuscript codices, there are 235 fragments in the Rosenthal Medieval Manuscript Collection alone. These date from the ninth century C. E. on, and some of the fragments are unidentified and undated. Just what I needed!

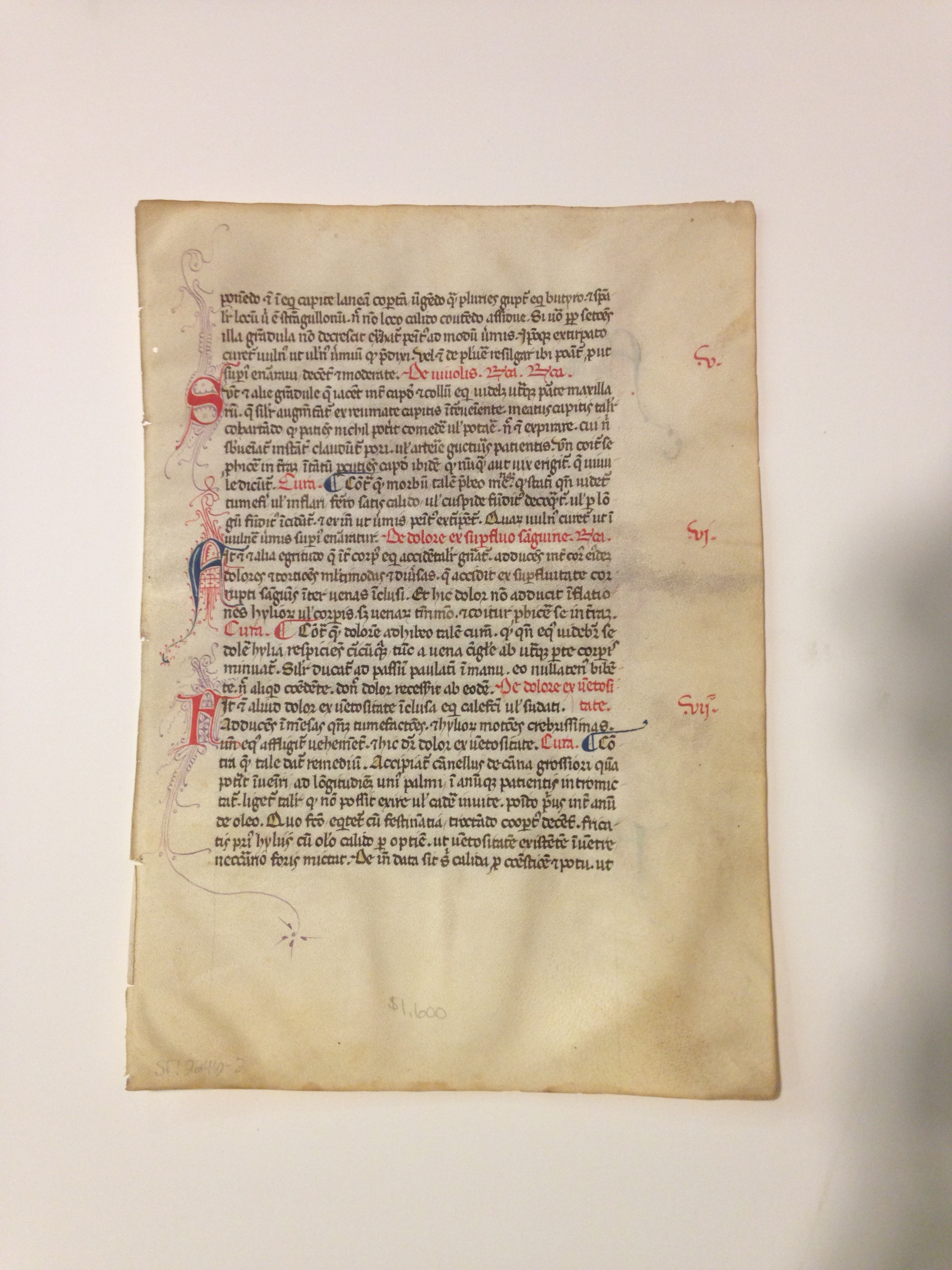

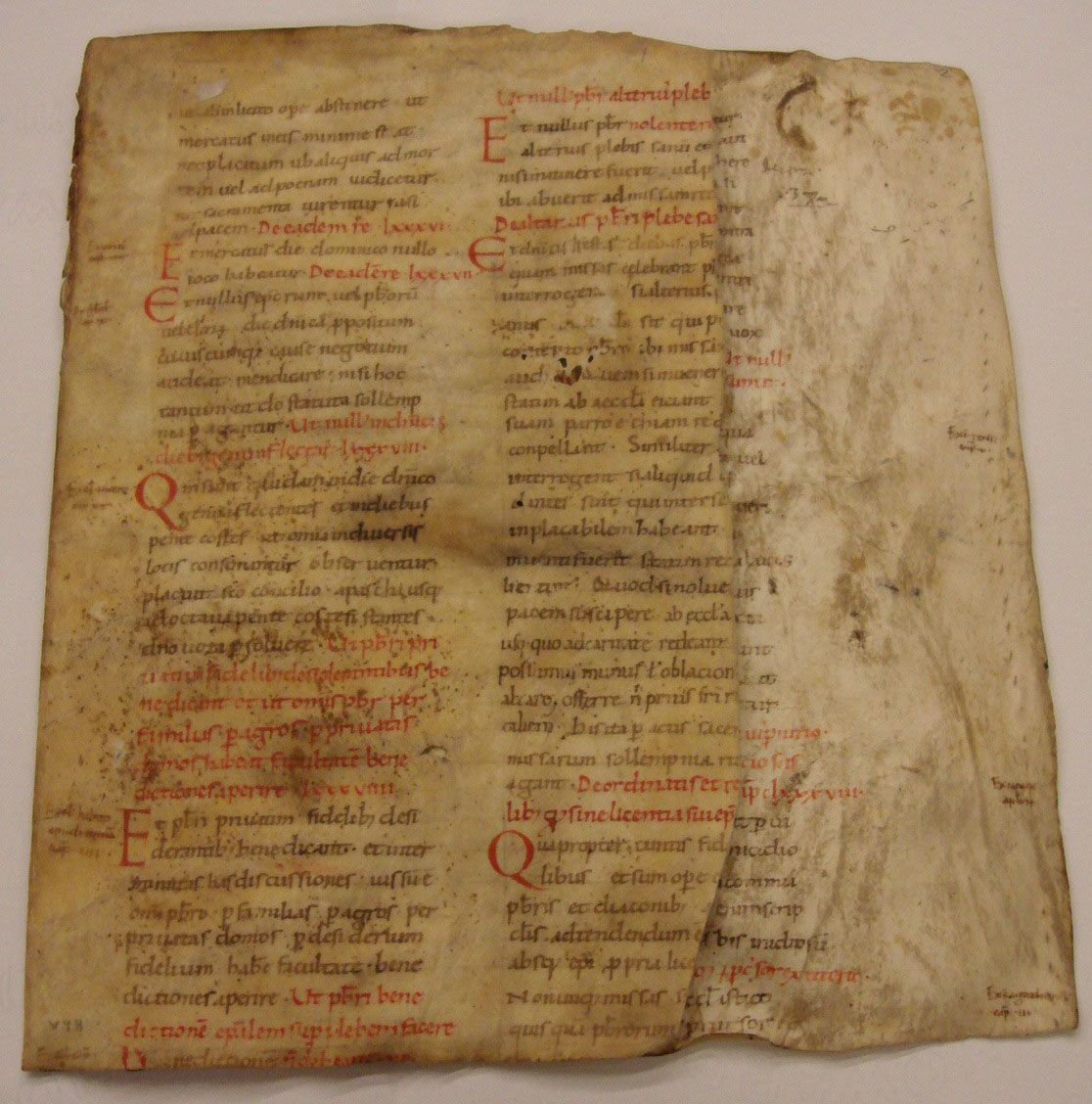

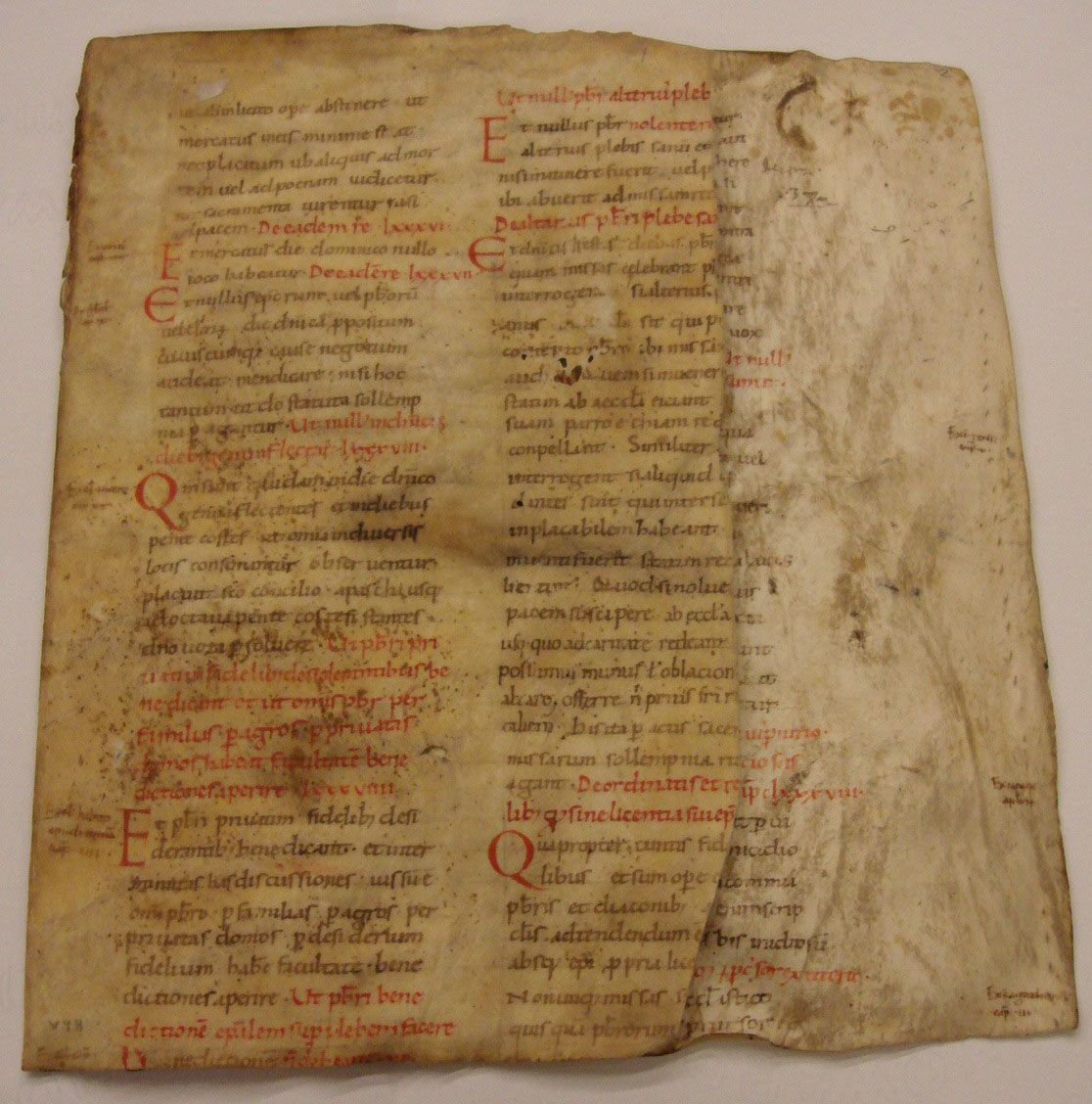

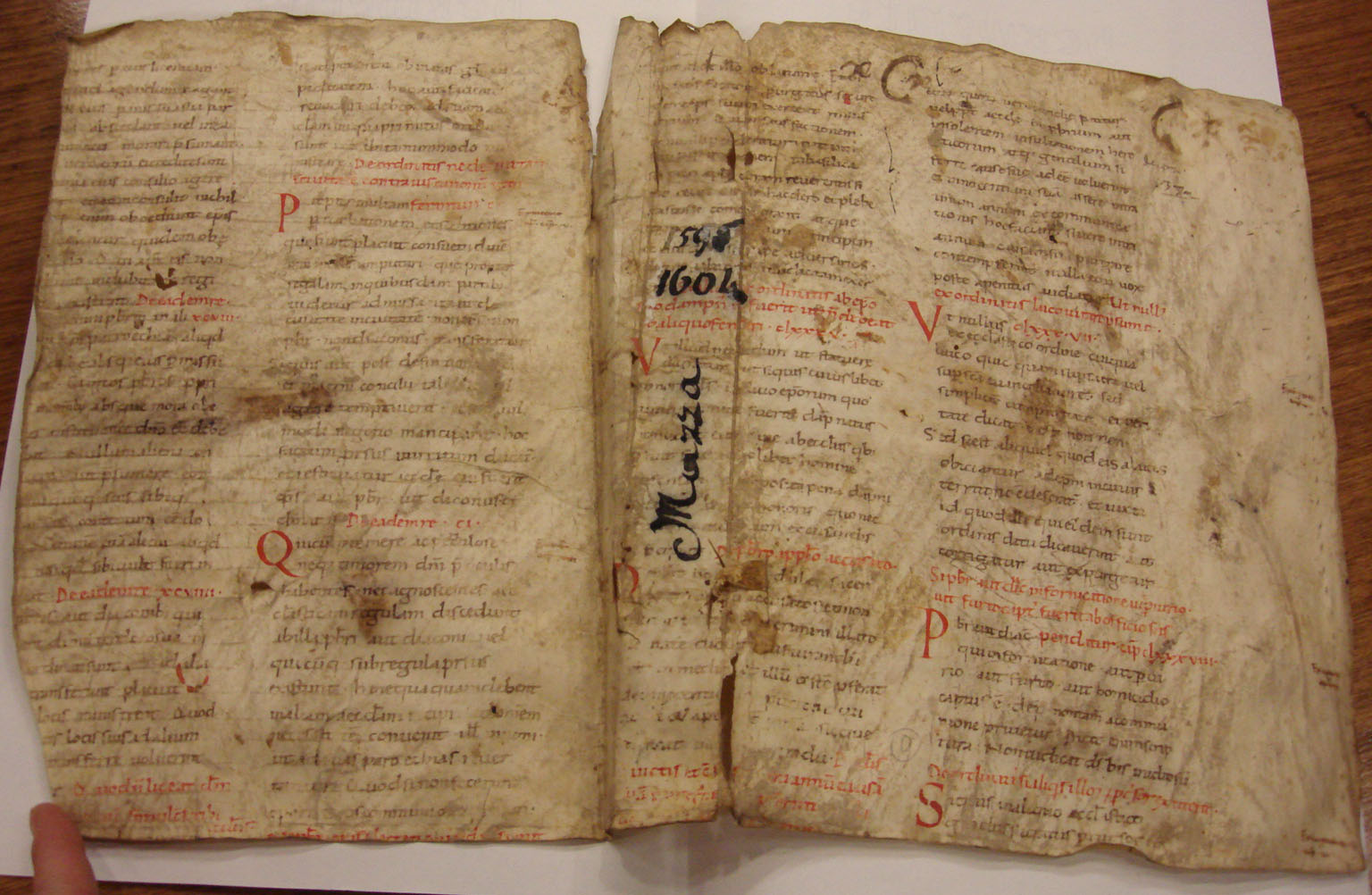

Unidentified fragment from the Rosenthal Medieval Manuscripts Collection. (MSS 9772. Photograph by Anne Causey)

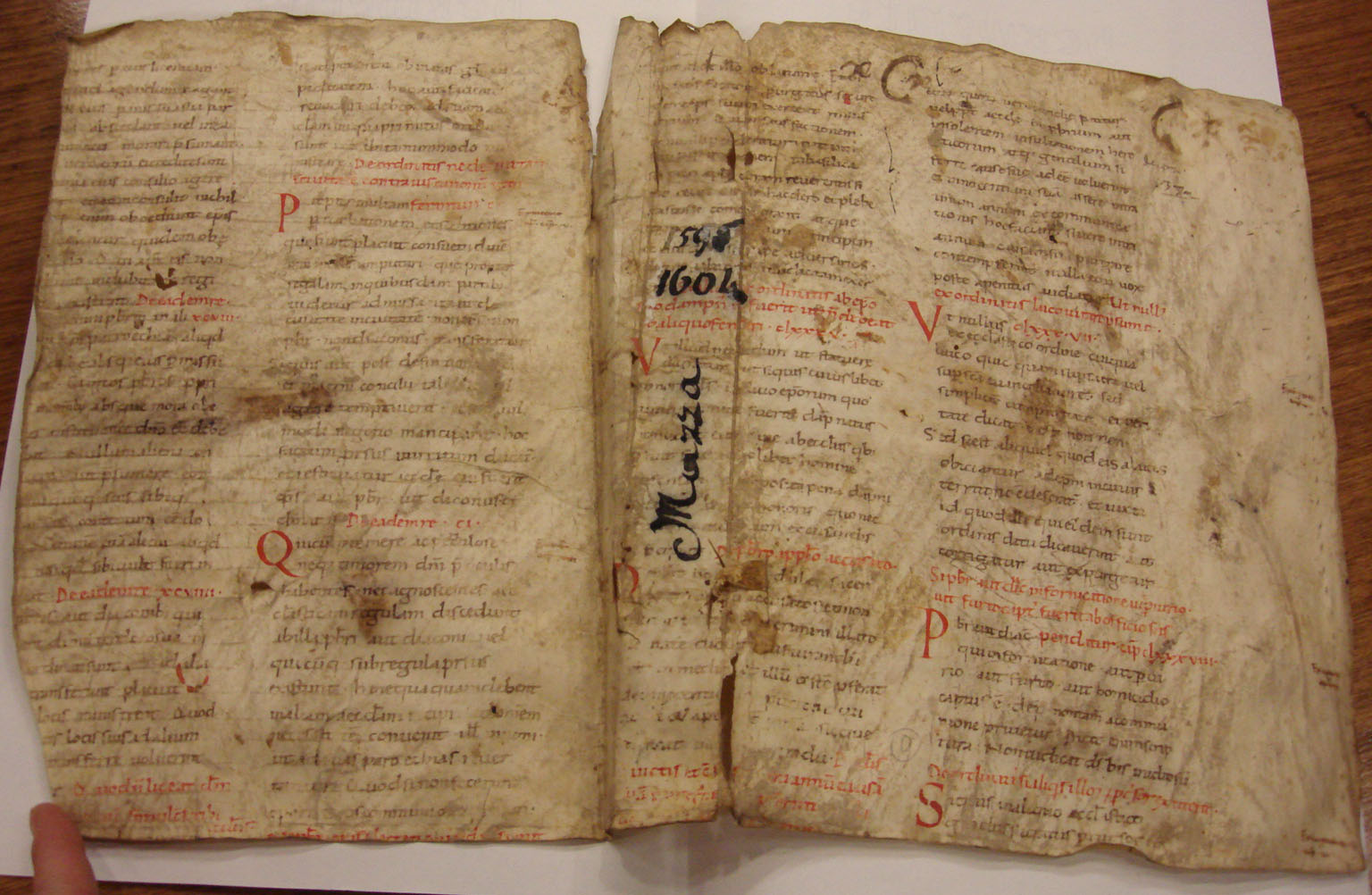

The Rosenthal manuscripts were purchased in 1972. The collection contains no pre-800 manuscripts because they are so rare and expensive; interestingly, a note in the collection indicates that just one of these earlier fragments would have cost almost as much as the entire collection. Most of the fragments are vellum, though some later leaves are paper; many were reused as covers for archival bundles or book bindings and show traces of use such as fading, stains, cut edges, remains of glue, and pen and ink scrawls.

There is nothing identifying the fragment, so we must examine it for clues. You will notice the black ink written in the middle–down the “spine.” That was likely added later when the fragment was used to rebind a book. On the right side of the fragment, there is a wrinkled pattern, and it is slightly translucent–probably what Professor Johnson referred to as the “saggy bits,” either from a shoulder or neck of the animal. On the far right edge, you can see holes that were probably prickings made to help rule the page for the scribe. (MSS 9772. Photograph by Anne Causey)

The Rosenthal Collection is not the only place to find medieval fragments at the Small Special Collections Library. There are 20+ manuscript fragments in the Atcheson Hench Collection.

I look forward to using all I learned regularly in my job, whether it’s assisting researchers and students in the reading room or teaching undergraduates how to start understanding these beautiful artifacts.

This amazing course was FREE, underwritten by sponsors in South Carolina, including The Humanities Council of South Carolina, Irvin Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, College of Arts and Sciences, and the Department of English at USC. Also, Scott James Gwara, professor of English and comparative literature at USC, was a most generous host who added his knowledge of Latin and medieval manuscripts to the class.