Now that we have your attention, in this post we feature a miscellany of recent book acquisitions.

An account of two balloon ascensions made in Valencia, Spain on March 12 and 15, 1784. The first was unmanned; the second carried “un gato grande.” (Photo by David Whitesell)

Before the rise of newspapers, news was often disseminated in the form of inexpensive pamphlets sold in bookshops and hawked on the street. We recently acquired the second recorded copy of a most unusual relación printed in Valencia, Spain and dated March 24, 1784. Its unnamed author describes what are perhaps Spain’s earliest balloon ascensions, undertaken only nine months after the Montgolfier brothers first launched their hot air balloon. The Spanish balloon, constructed primarily of paper and measuring 18 x 12 feet (1103 cubic feet), was smaller than the first Montgolfier balloon. Its six-panelled blue surface was lavishly decorated with the arms of Valencia and King Carlos III, an inscription from Homer, and other decorations appropriate for a pioneering aerial billboard. At 5:15 p.m. on March 12, 1784, the balloon ascended from an orchard just outside Valencia’s city wall, soon disappearing into the clouds before landing one league distant from the city. After some repairs, the balloon was relaunched from the same site on March 15, this time with “una jaula de alambre con un gato grande dentro de ella” (a wire cage with a large cat inside) suspended beneath. The balloon rose to a height of approximately 3,000 feet, then hovered motionless for ten minutes before making a gentle five-minute descent. Presumably the cat had much to say upon landing but, because it immediately clawed its way free and fled, its feelings about having been “el primer viajante aëreo de su especie” (the first aeronaut of its species) have been lost to posterity. We have found reference to a cat being sent aloft in a French balloon exactly one month earlier, on February 15, 1784, but it did not survive the flight, so the Spanish gato may well have been the first successful feline aeronaut. This relación joins the Small Special Collections Library’s extensive aeronautical history collection.

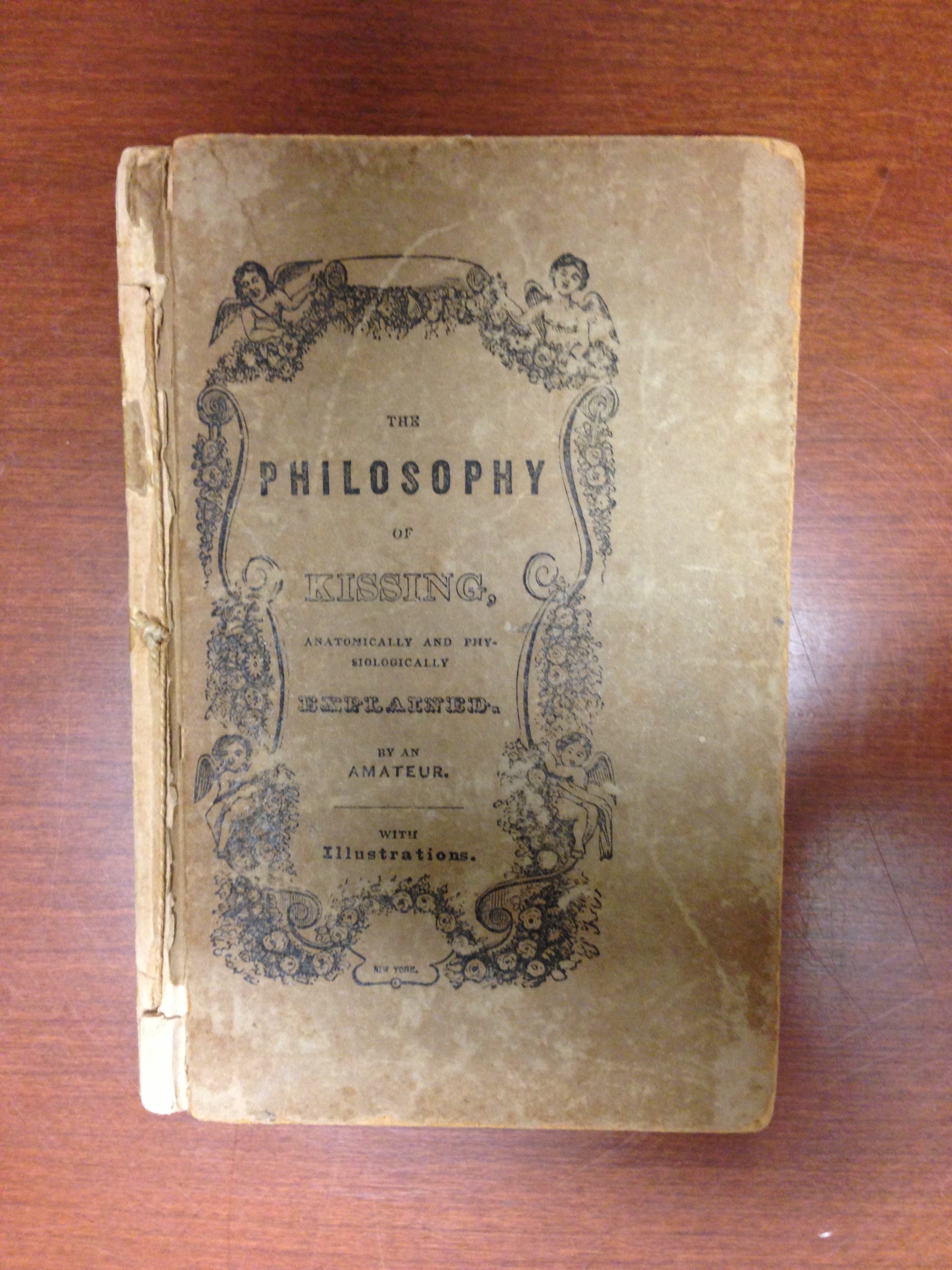

Original printed front cover to The Philosophy of Kissing, Anatomically and Physiologically Explained. New York: R.H. Elton, 1841. (Photo by David Whitesell)

The second quarter of the 19th century saw a profusion of popular works devoted to courtship and marriage. Most were issued in a small, portable format and, to make them suitable for gift giving, dressed in attractive bindings. The Philosophy of Kissing, Anatomically and Physiologically Explained (New York, 1841), is one of the more unusual. The book’s perspective is stated up front: “Even Sir Isaac Newton, great philosopher as he doubtless was, kissed, and was kissed, though by no means to a remarkable extent, yet never enquired the WHY–never discovered the WHEREFORE. It was reserved for a later era and a more philosophical age … He ascertained existing phenomena, but found not the cause.” Perhaps so, but one might well add, tongue in cheek, that Newton fully understood the principle of gravitational attraction. The book might have been more successful—only one edition was published—if it had focused more on the how than on the why. This copy retains its original illustrated covers and contains a number of illustrations, including phrenological charts of the brain’s amatory regions.

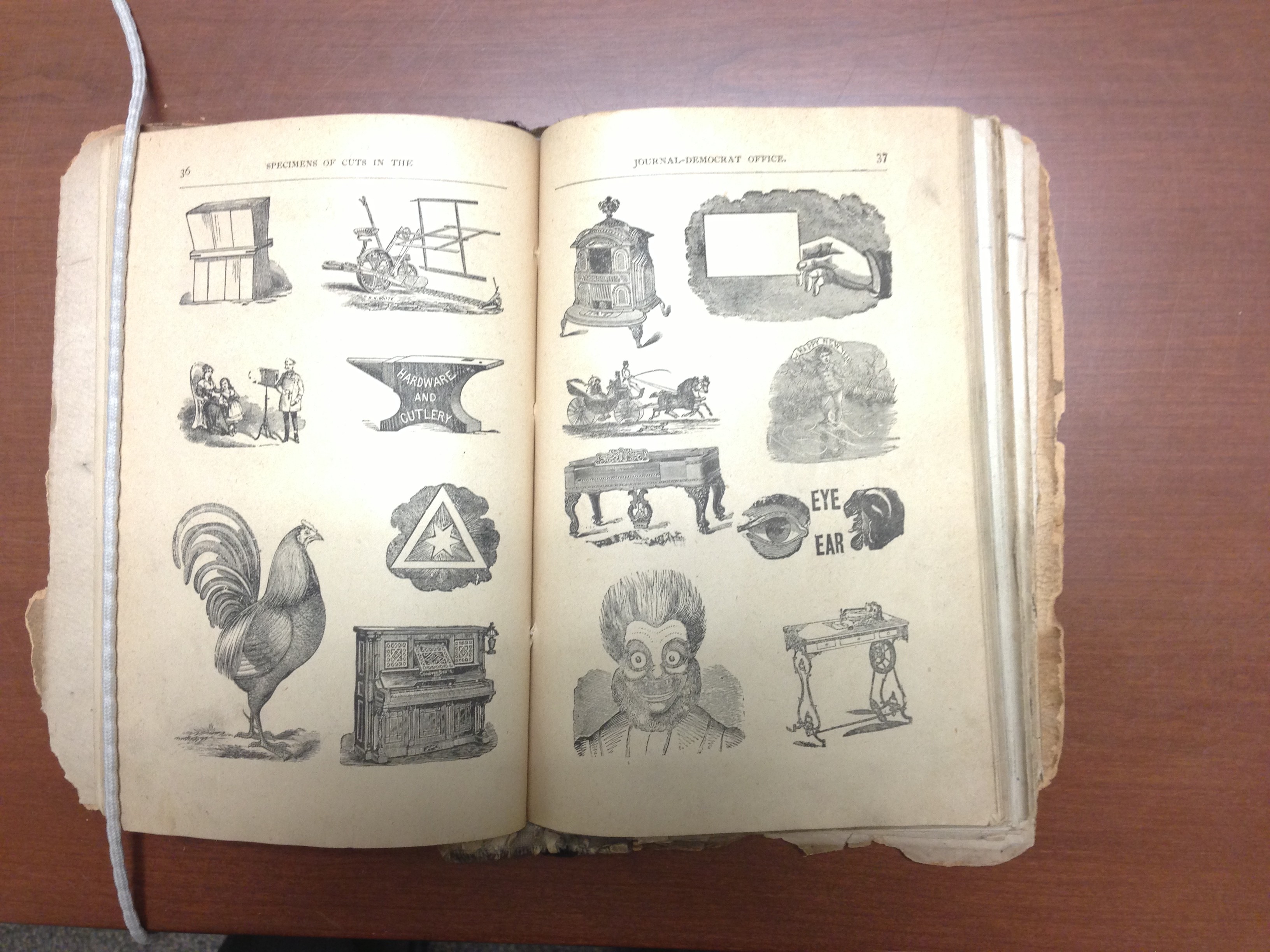

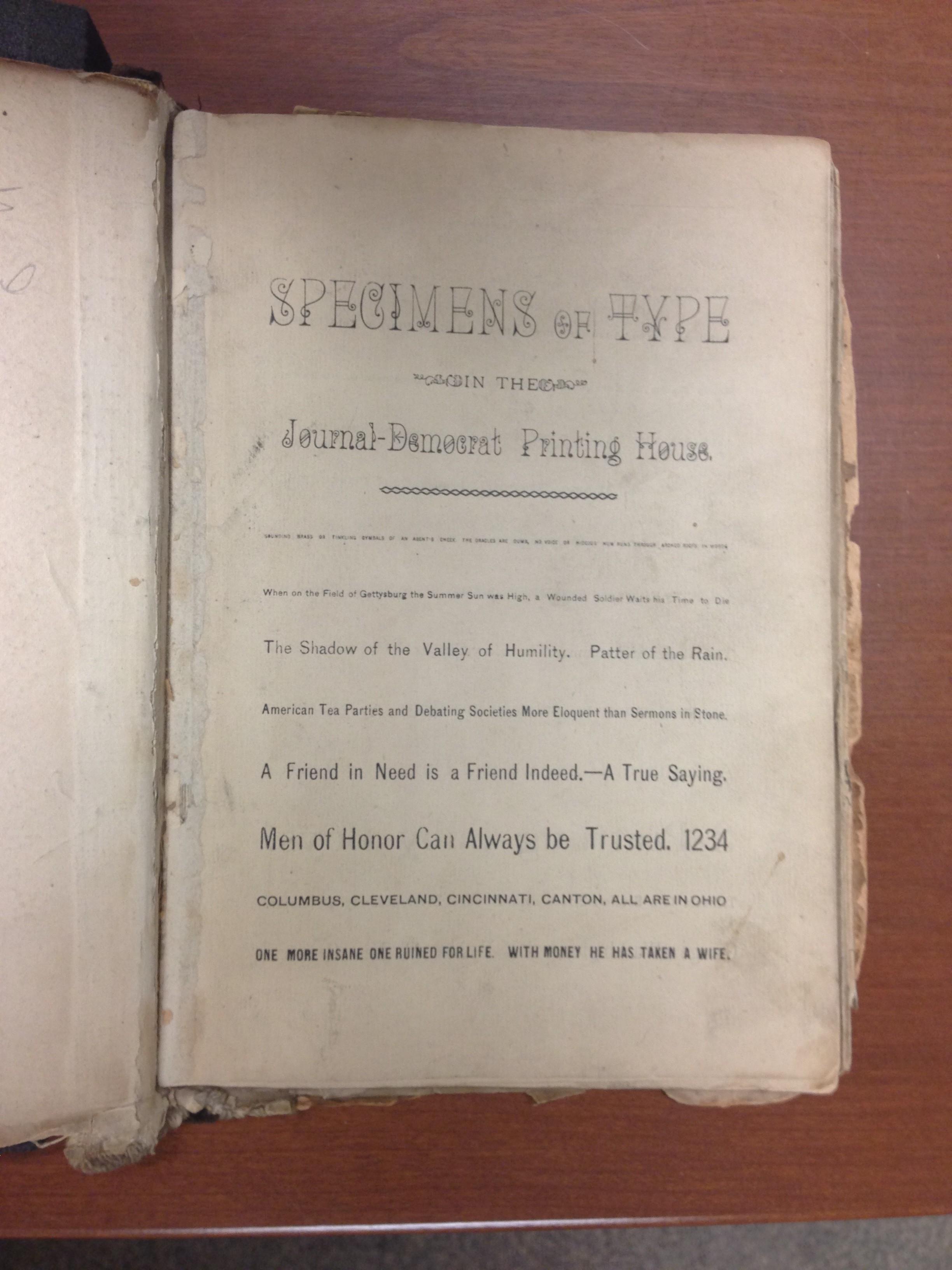

First page of Specimens of Type in the Journal-Democrat Printing House (Warrensburg, Mo., ca. 1885), showing the smallest text types available in this printing shop. The textual snippets selected for typesetting are fascinating in their own right. (Photo by David Whitesell)

The Small Special Collections Library boasts a large collection of type specimen books dating back to the 18th century. These can be either specimens issued by typefoundries, alerting printers to the typefaces, ornaments, and vignettes available for purchase; or specimens issued by printers, showing potential customers what resources were on hand for their book and job printing needs. Type specimens range in format from simple broadsides to massive, finely printed trade catalogs. Because most soon became outdated and were discarded, today many type specimens are rare. Although particularly useful to the bibliographer and printing historian, type specimens are valuable sources for investigating the nexus between print and society. One recent acquisition is the only known copy of a type specimen issued ca. 1885 by a rural Missouri printer: Specimens of Type in the Journal-Democrat Printing House. The Journal-Democrat was published out of Warrenton, Missouri and, like many newspapers of the time, also printed pamphlets, the occasional book, and especially all manner of jobbing work: blank forms, letterheads, posters, fliers and the like.

This specimen book begins with 18 pages of typefaces in various sizes and decorative styles, most far more suited for jobbing work than for books. Following are 60 pages of ornaments and stock cuts akin to today’s clip art, which provide a unique window into what a frontier printing shop thought appropriate for its clientele.

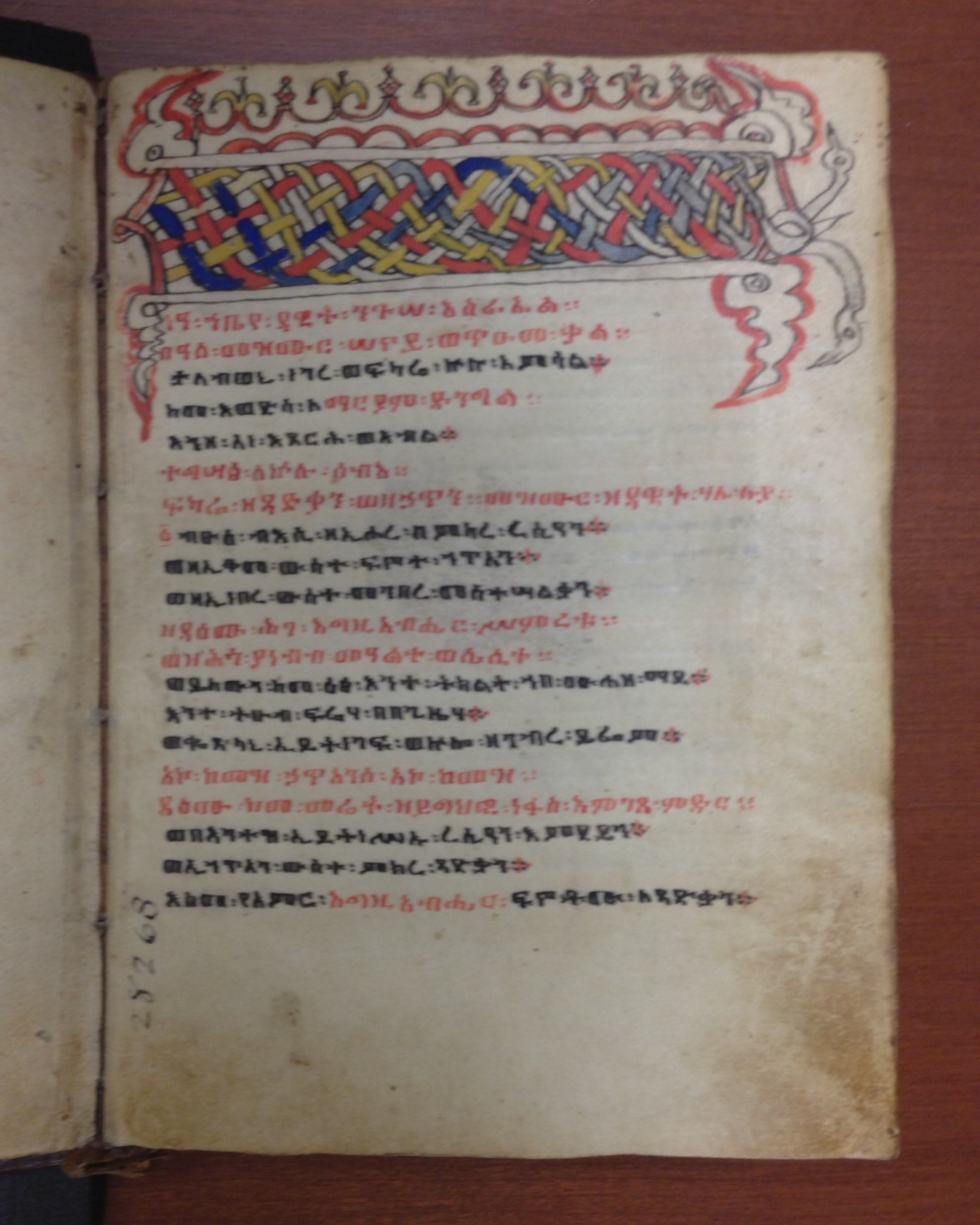

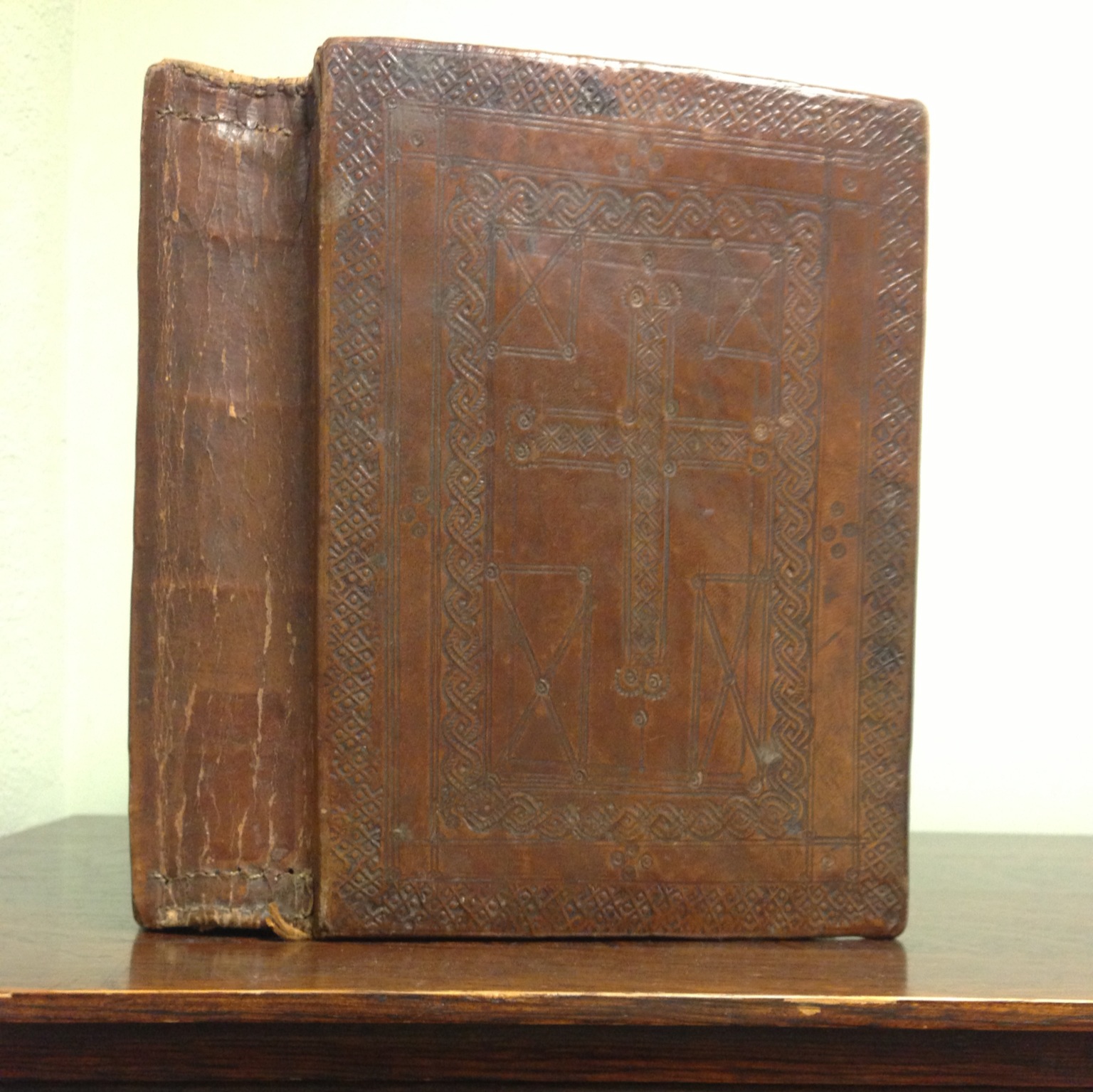

Spine and front cover of the Mäzmurä Dawit, an early 19th-century Ethiopic manuscript of the Book of Psalms. (Photo by David Whitesell)

Our collection of medieval manuscript codices, fragments, and single leaves on vellum, parchment, and paper, receives constant use from U.Va. classes, Rare Book School courses, and scholarly researchers. The manuscripts are valuable for any number of reasons, including their texts, what they reveal about the materials and methods of medieval book production, manuscript illumination, and paleographical studies of the various scripts employed by medieval scribes. We recently acquired a manuscript codex which, we hope, will prove useful in the classroom for placing the medieval book in broader perspective.

This finely preserved manuscript of the Mäzmurä Dawit, or Book of Psalms, is written in Ge’ez, the liturgical language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. It dates to the early 19th century but looks centuries older. Indeed, it wonderfully demonstrates the close ties between the Western European manuscript tradition and the earlier, and more persistent, Christian tradition from which it sprang. In appearance its blind-tooled goatskin binding over thick wooden boards resembles a 14th-century European binding. Its parchment leaves were prepared and written using traditional methods that Europe had largely abandoned three centuries earlier as it embraced the printed book. And in terms of illumination and binding construction, it is uniquely Ethiopian.

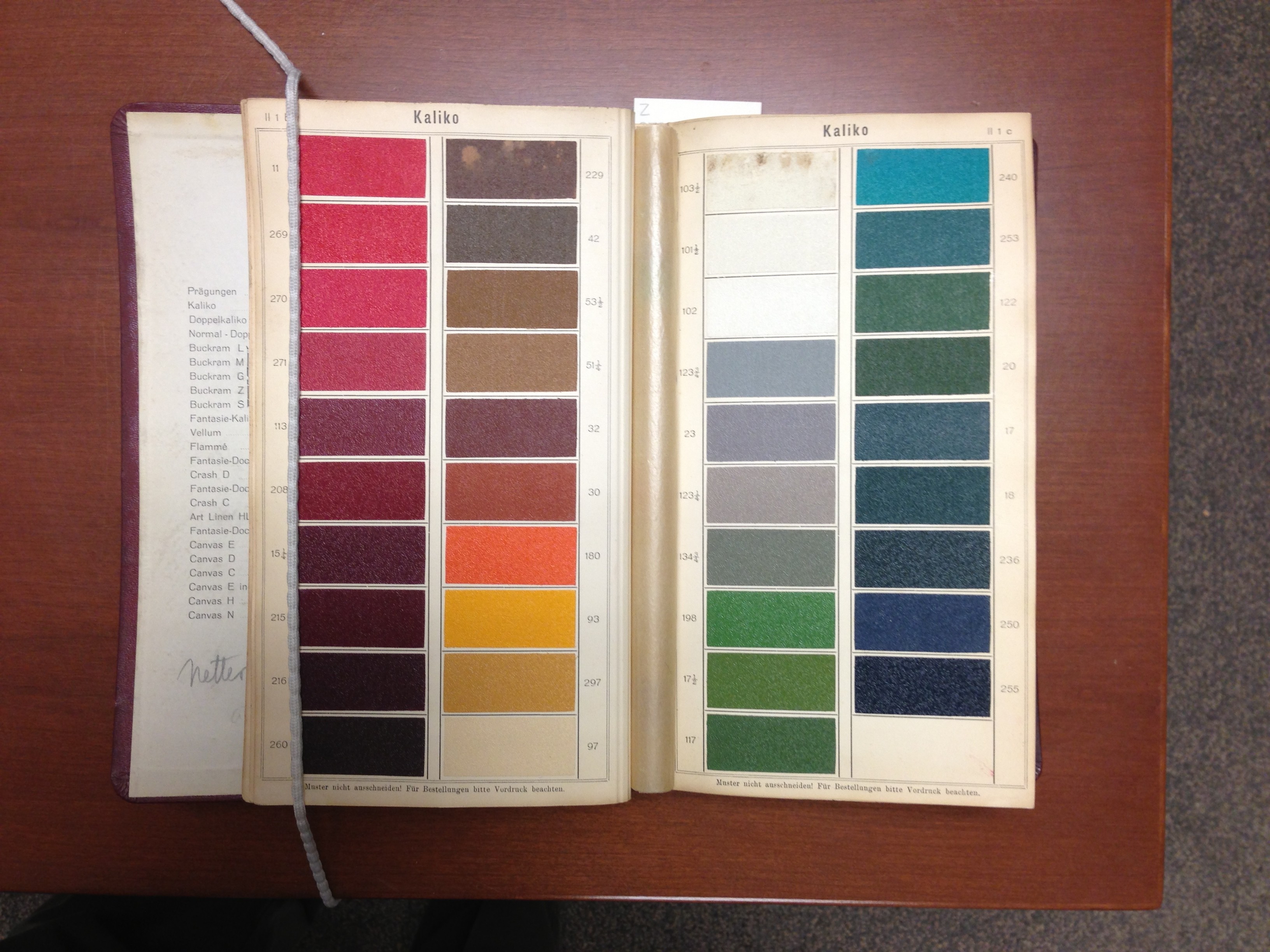

Two pages from Netter & Eisig’s Bucheinbandstoffe sample book (Göppingen, ca. 1912), with mounted cloth samples showing the range of colors in which this particular fabric was available. (Photo by David Whitesell)

From the 1820s onward, many books have been issued in “publisher’s cloth bindings,” i.e. bound in decorative cloth bindings prior to public sale. Bibliographers, booksellers, collectors, and library catalogers have traditionally described these in simple terms: “bound in publisher’s red cloth, gilt.” Recently bookbinding historians have come to understand that, by consulting sample books distributed to commercial binderies by bookbinding cloth manufacturers, it is possible to describe publisher’s bindings far more precisely. Such sample books are of legendary rarity, in part because the bookbinding cloth market was dominated by a handful of firms, who typically demanded the return of old sample books before new ones were sent. Hence we were delighted to acquire a fine, complete, and previously unrecorded copy of the Bucheinbandstoffe sample book issued ca. 1912 by Netter & Eisig of Göppingen, Germany. Included are 585 mounted samples of some 45 different fabrics showing the range of colors, qualities, and grains available. The first three pages provide samples of 48 different specialty grains which could be embossed into most cloth rolls prior to shipment. These cloths can be found on tens of thousands of publisher’s bindings for early 20th-century continental European imprints.