Today, the folks over at UVA’s facebook page invited curator Molly Schwartzburg to share with them some of her favorite items in the miniature book collection on the Facebook Live streaming video platform. For those of you not on Facebook, here’s the video. We’re impressed that those teeny tiny books are actually in pretty good focus! Check out some of our beautiful and unusual minature treasures.

Monthly Archives: September 2017

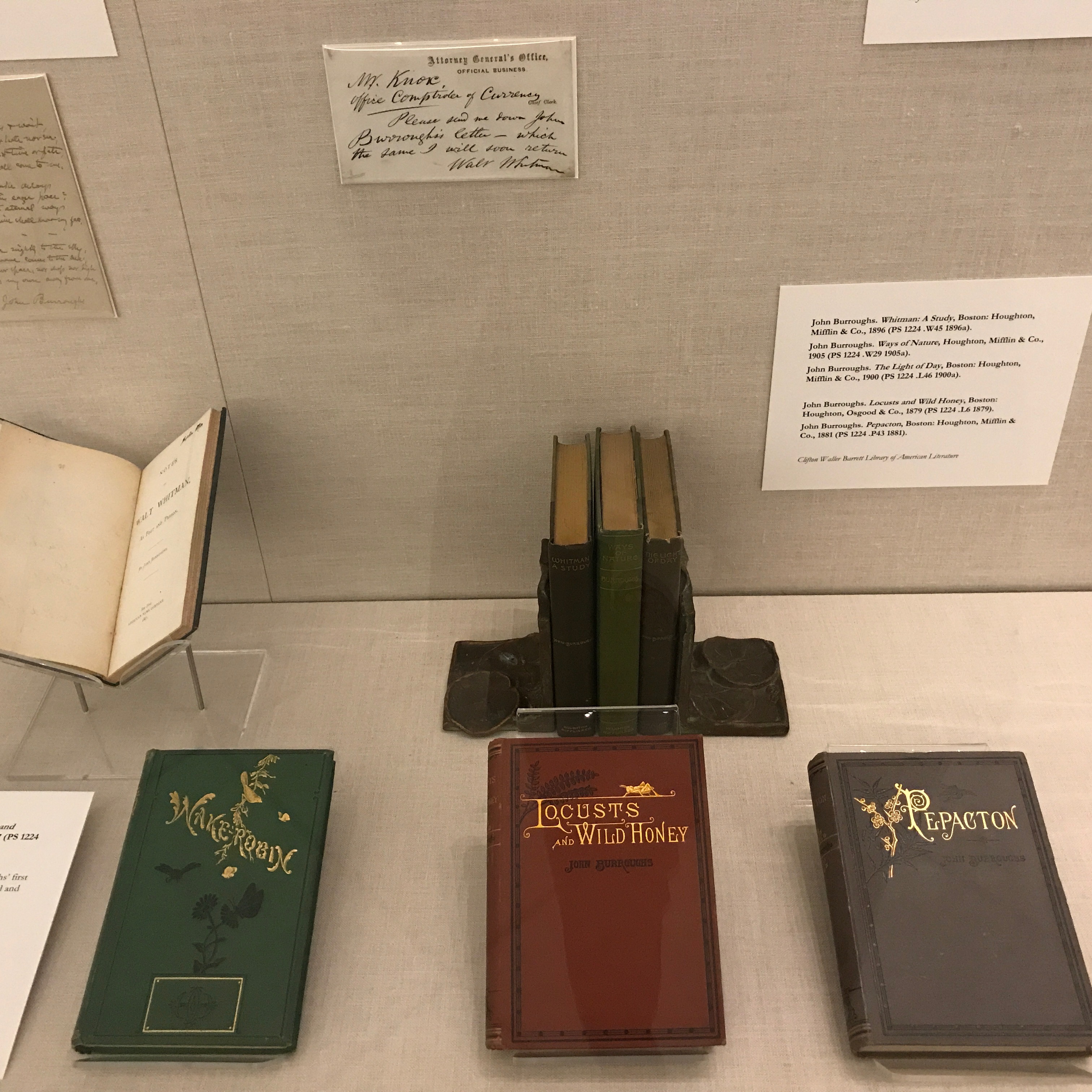

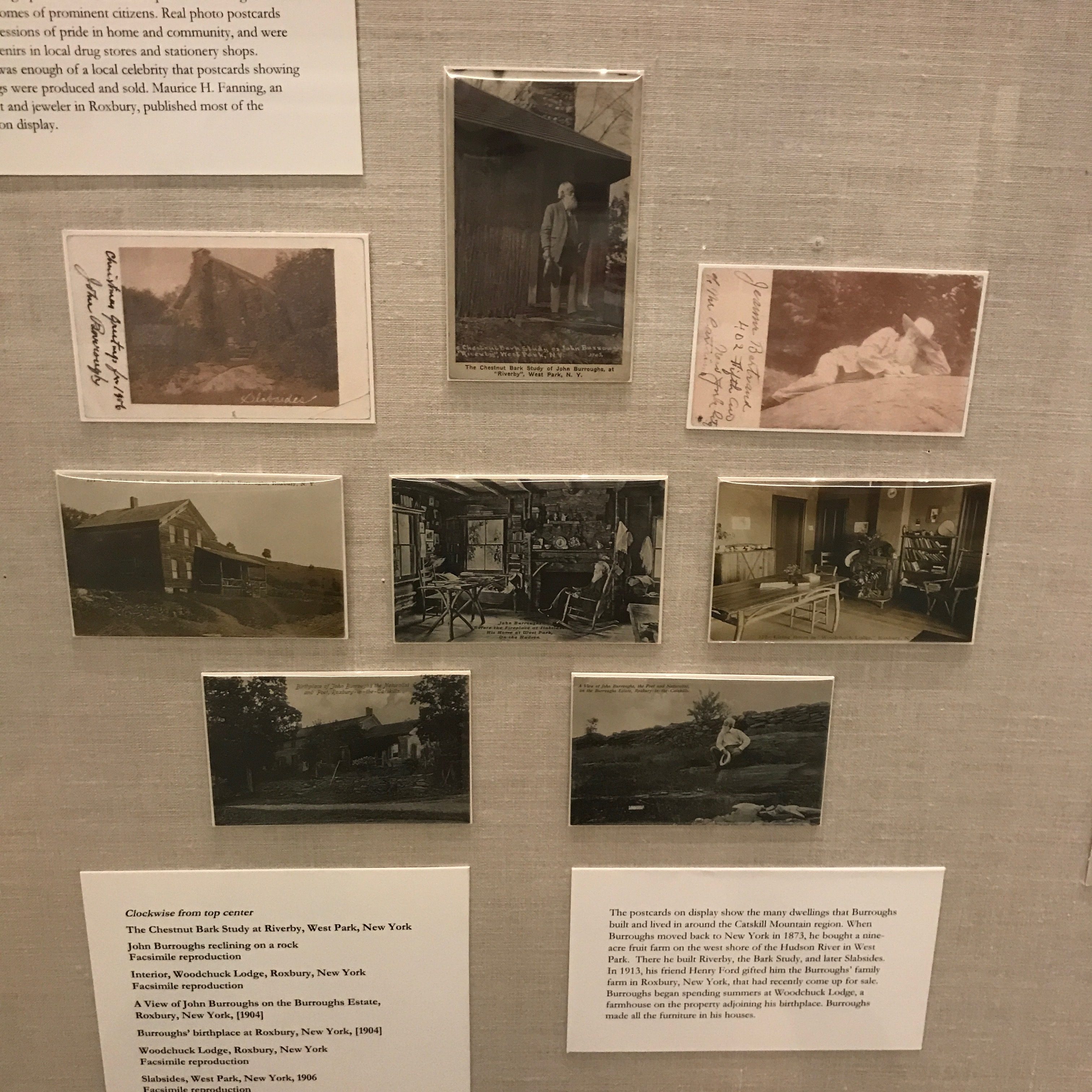

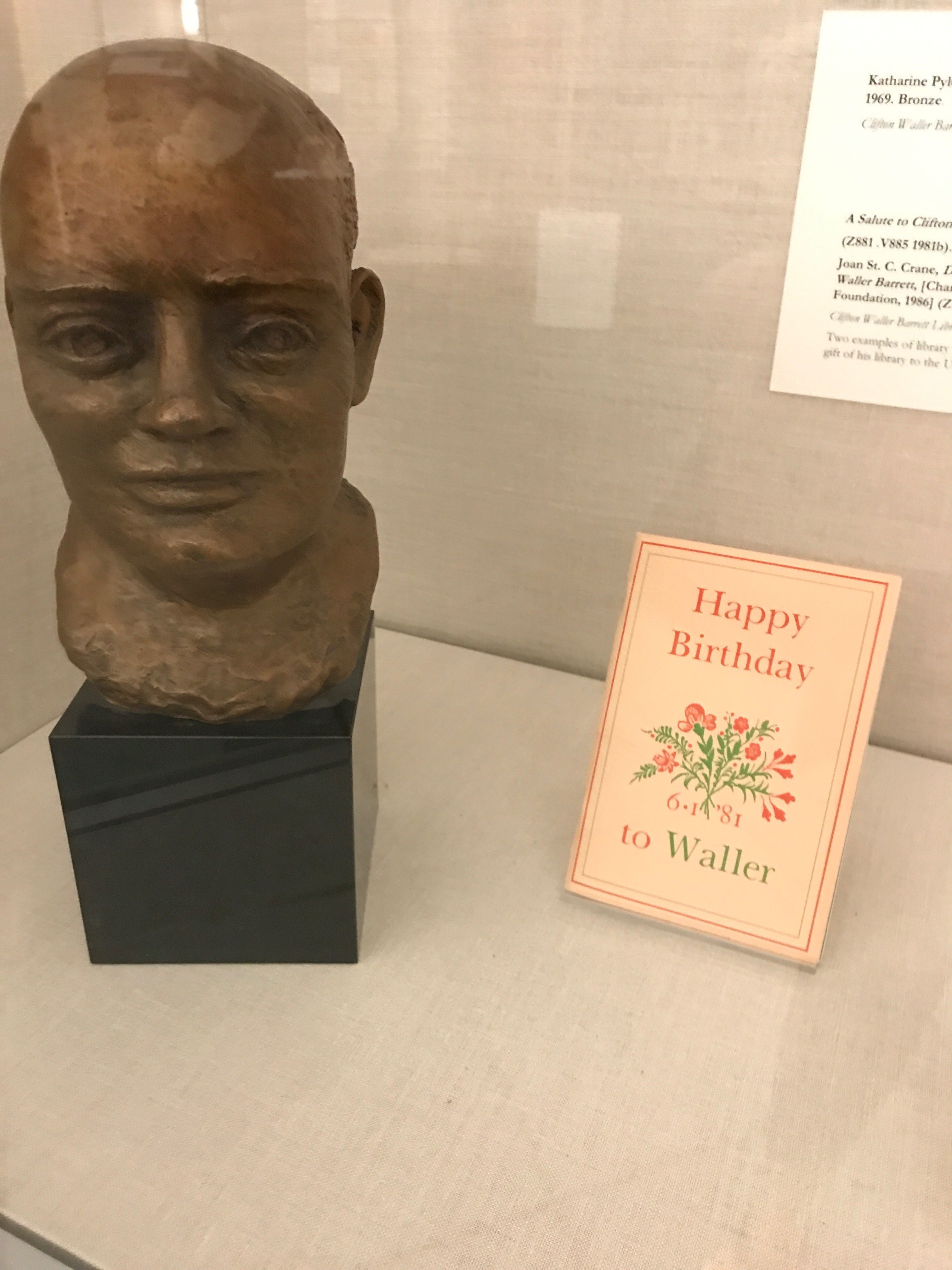

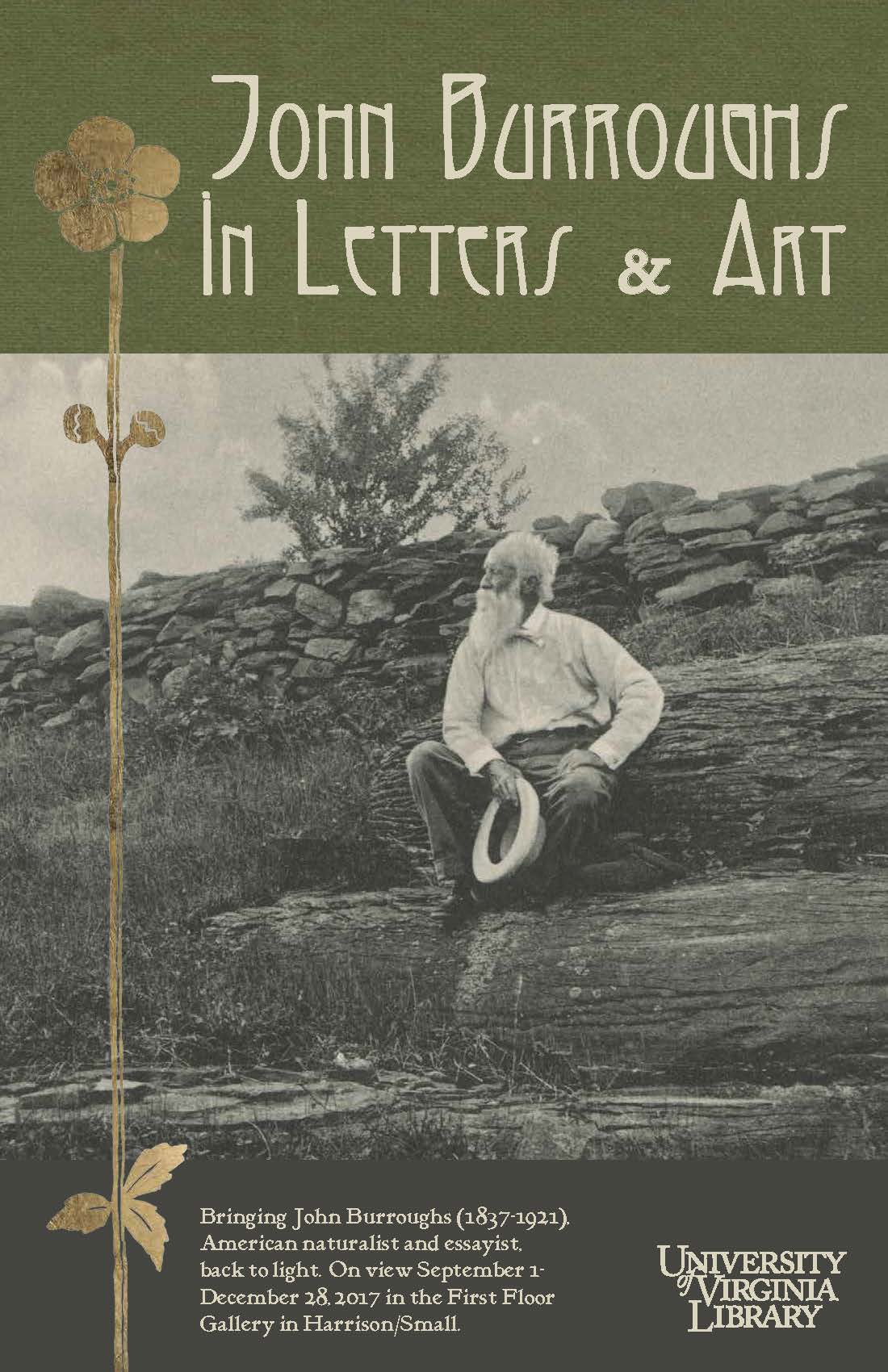

On View Now: “John Burroughs: In Letters & Art”

We are pleased to announce our latest First Floor Gallery exhibition, “John Burroughs: In Letters & Art.” It runs through December 28, 2017.

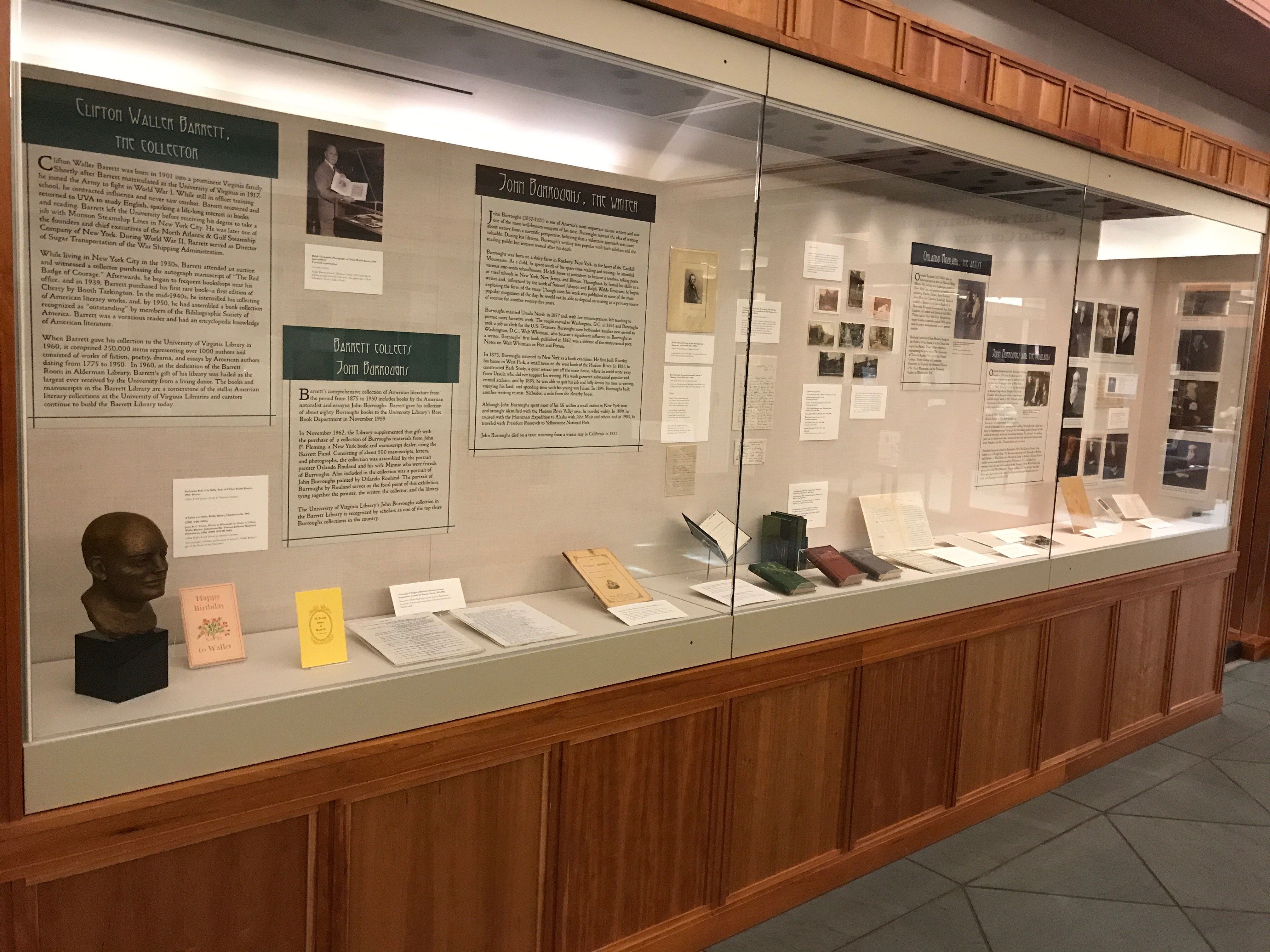

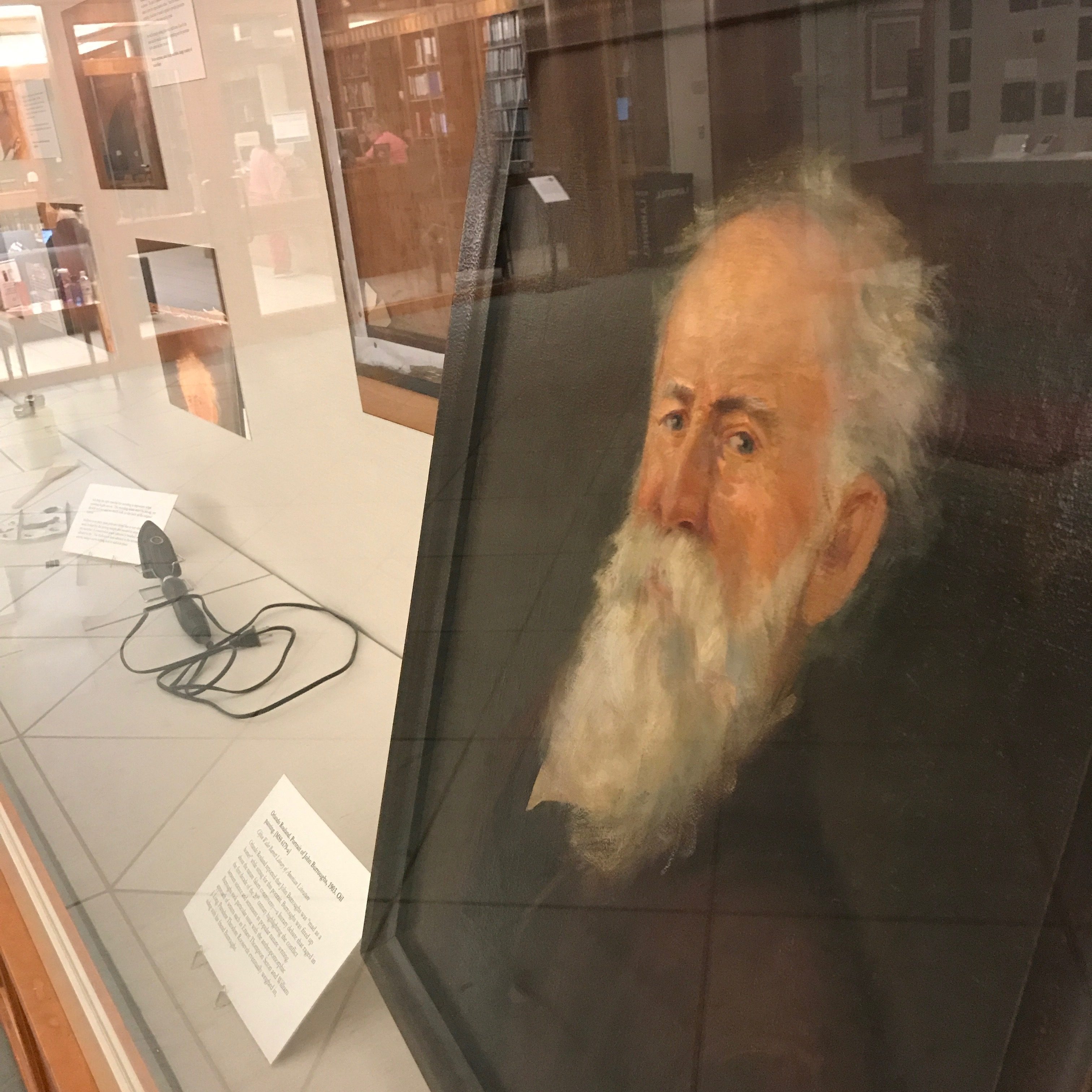

Inspired by the recent conservation treatment of a portrait of Burroughs painted by Orlando Rouland, this exhibition brings an important American naturalist back to light. The painting serves as the focal point of the exhibition, tying together writer, artist, collector, and library. The exhibition showcases books, manuscripts, and other materials from the Burroughs collection. John Burroughs’ (1837-1921) essays on nature were widely read by both scholars and the reading public during his lifetime. He counted among his friends prominent men including Walt Whitman, Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Ford, John Muir, and Thomas Edison.The Burroughs collection is part of the Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature at the University of Virginia.

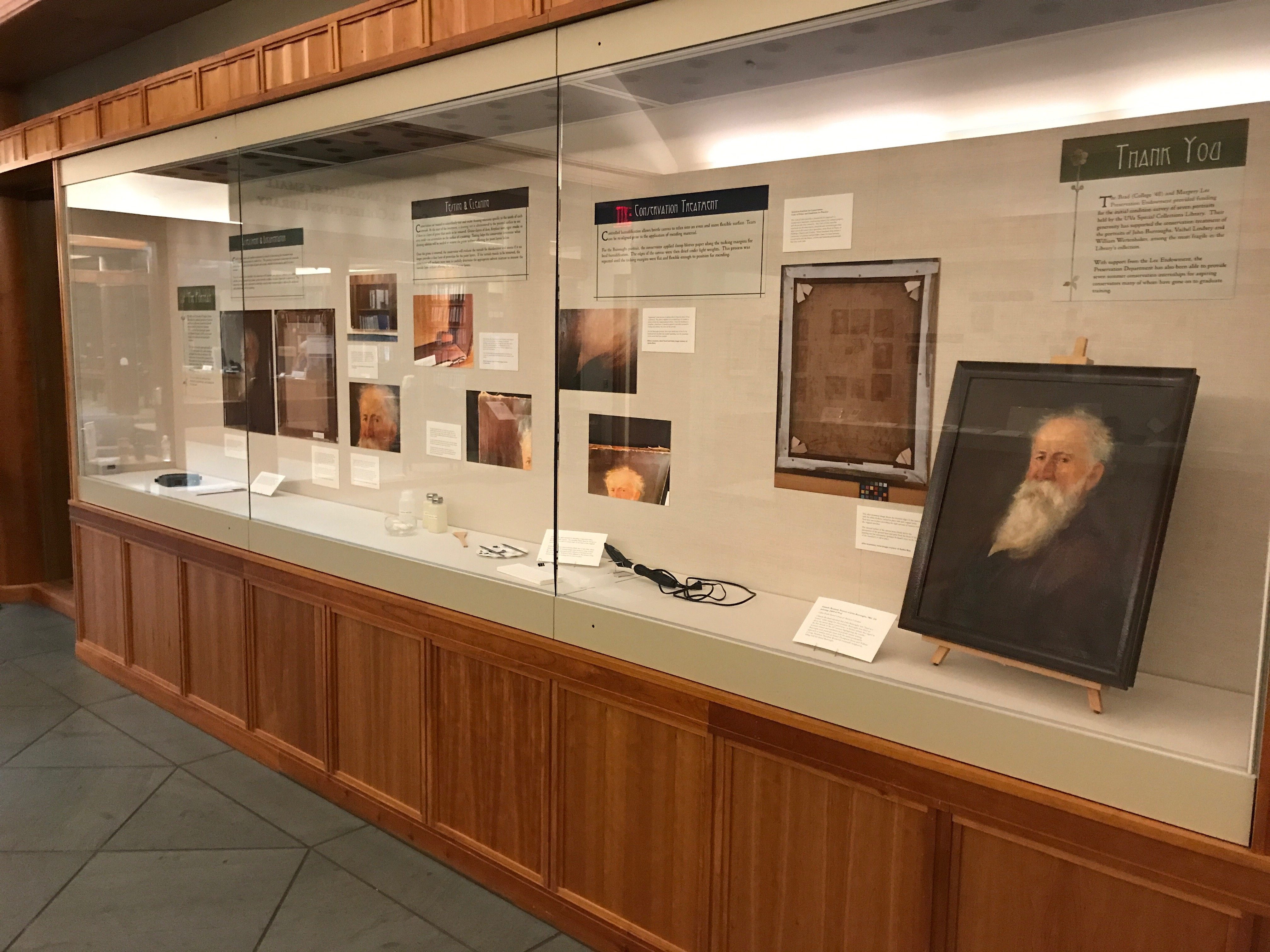

Here are a few tastes of the exhibition in photographs:

The portrait around which the exhibition was planned. Nearby are some of the tools used in its conservation treatment.

We look forward to seeing you in the gallery!

Identifying Early Shelf-Marks from the Rotunda Library

This week we are pleased to share a guest post by two graduate students in the English department, Neal D. Curtis and Samuel Lemley who are currently doing research for a grant-funded project on the early history of the UVA Library. Neal, a 3rd-year PhD student, specializes in bibliography and the eighteenth century. Sam, a 4th-year PhD candidate, is working on a dissertation on antiquarianism as a literary mode in early modern England. Their project on the Rotunda Library is funded by a William R. Kenan Grant, an International Center for Jefferson Studies (ICJS) fellowship, and a research grant from the Institute of the Humanities and Global Cultures (IHGC) at UVA.

As part of an ongoing project on the design, history, and layout of the University of Virginia’s first library, we spent two weeks in the late summer this year deciphering cryptic shelf-marks in books. A shelf- or press-mark is a letter, number, or other sign stamped inside or on a book that signals the book-press, case, or shelf to which the marked book belongs. Often overlooked, historical shelf-marks can bring to light the provenance of individual volumes and reveal the ways in which collections were shelved and accessed in the past—a big deal for bibliographers and book historians.

The approximately 3,100 books (8,000 volumes) originally shelved in the Rotunda are known, thanks to a 29-chapter catalogue printed in 1828. This catalogue makes reconstituting the University’s first library relatively easy, but its historical arrangement in the Rotunda remains obscure. This is due in part to the scant information provided by the catalogues that survive. The 1828 catalogue and its 1825 manuscript precursor list titles, authors, and dates, but don’t specify how the books were arranged on the Rotunda’s shelves. A later catalogue, begun in 1857, adds shelf numbers beside each title, but presumably the books were also marked to prevent mis-shelving and loss.

In search of these hypothetical marks, we began by examining the first fifty books listed in the 1828 published catalogue. All of these books are classed in Chapter One (“Ancient Languages”), and most are still held in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library—a result of the fact that this section of the Rotunda library was shelved on the main floor of the dome room rather than in the upper galleries, which burned along with the books they held in 1895. (But that’s a story for another time…)

Our search revealed three types of shelf-mark, each representing a phase in the history of the collection:

1.

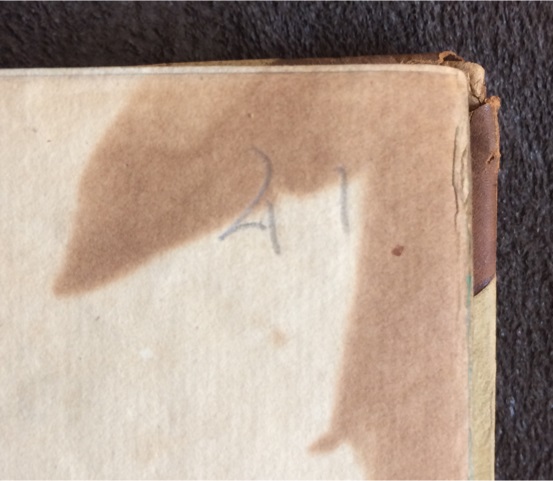

Type 1 shelf-mark: “41”, ca. 1825 (PA3458 .A2 1794, vol. 1)

The first and earliest type is rudimentary: a number penciled on the front flyleaf of each volume, indicating the chapter or subject heading to which the marked book belongs. This number evidently refers to chapter headings in 1825, and not those in 1828. We know this because the pencilled numbers fit a 42-part (or chapter) system employed in 1825 rather than the 29-part system devised in 1828. To clarify by way of example, a book that would be categorized in Chapter 1 (“Ancient Languages”) in 1828 is here labeled “41”, for Chapter 41 (“Philology”) in 1825. Confirming this prediction, the same book appears in the first chapter of 1828 and the 41st chapter of 1825.

2.

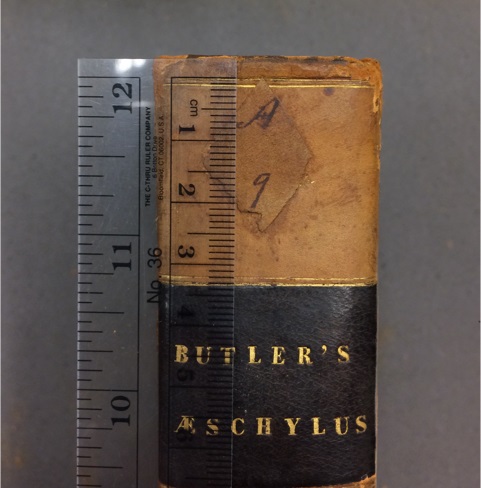

Type 2 shelf-mark: “A | 9”, ca. 1828 (PA 3825 .A2 1809a)

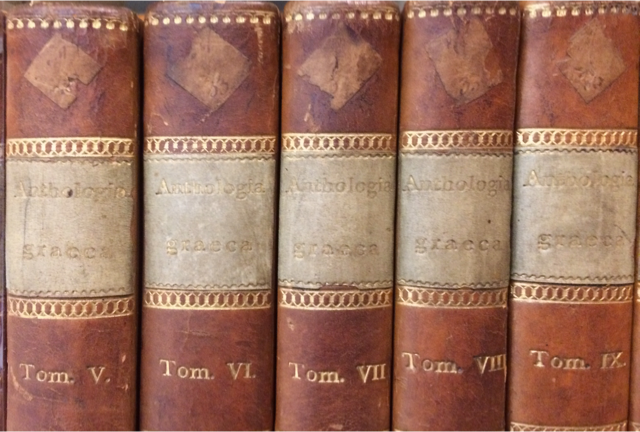

A set of books originally shelved in the Rotunda showing early shelf-marks on spines. (PA3458 .A2 1794, vols. 5-9)

The second type of shelf-mark is a small, diamond-shaped leather label pasted at the head of the spine of each volume. These labels list the shelf and position of each book in an alphanumeric shorthand. For example, the label pictured here specifies ‘A9’—that is, the book 9th in sequence on the shelf labelled ‘A’. Presumably the librarian would have known the case number based on the subject of the book; otherwise, the case number could have been found by consulting the catalogue and finding the book under the appropriate chapter heading. Evidently, this shelf-marking system endured: next to the same title in the 1857 catalogue appears ‘1A’, meaning that this book was shelved in the first case on the first shelf from ca. 1828 until ca. 1895, when the 1857 catalogue was replaced.

3.

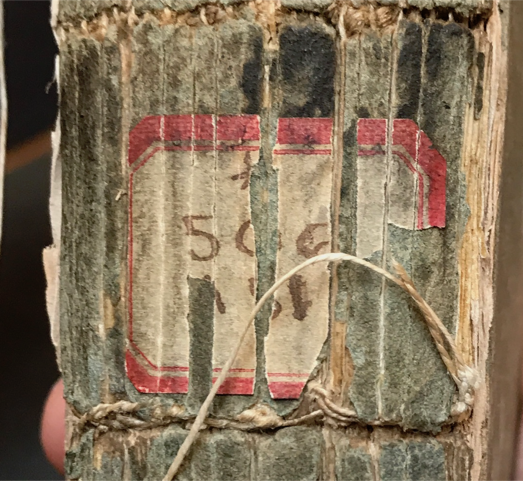

Type 3 Shelf-Mark, illegible. (Q11 .P6 n.s. v.2 1825)

Type 3 Shelf-Mark (trace): DDC call no., ca. 1896-1906 (PA3458 .A2 1794, vols. 1-2)

The third and latest type of pressmark is a red and white paper label pasted at the foot of the spine of each volume. Unfortunately, these survive only in fragments, and most have been removed entirely. However, the ink from some of these shelf-marks bled through, staining the leather underneath.These traces reveal that the call numbers on these labels belonged to Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC)—a system of library organization invented in 1876 and only implemented at the University of Virginia from ca. 1896 to 1906. It’s therefore safe to assume that these labels were added after the fire in 1895 when books were reclassified and re-shelved in the newly-renovated Rotunda. Presumably these labels were removed when the books were re-catalogued according to the Library of Congress Classification (LCC) system and transferred to Alderman in the 1930s.

The implications for this discovery are far reaching. We expect that additional research will establish the number and size of the shelves in the Rotunda, the distribution and organization of volumes in each case, and the aesthetic of the books arrayed in their original order beneath the Rotunda’s dome. Identifying these pressmarks will also enable researchers and special-collections staff to approximate the date a particular book was added to the collection. All of this, we hope, will help us paint a detailed portrait of the university’s first library in use.