This post, by Manuscripts and Archives Processor Ellen Welch, introduces a new acquisition: the Madeleine Coleman Roach Papers (MSS 16869), documenting the service of a twenty-three-year-old African American woman, Madeleine Coleman, in the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion of the United States Women’s Army Corps during the Second World War.

The 6888th Battalion was an all-female mostly Black military unit that has been made famous by several books and movies—most recently in a 2024 film, Six Triple Eight, directed by Tyler Perry and filmed in Atlanta, Georgia; Chattanooga, Tennessee; and the United Kingdom (available on Netflix). The 6888th accomplished the near impossible feat of clearing a huge backlog of mail addressed to service members abroad. The women systematically sorted and routed an estimated backlog of 17 million items to over seven million service members in record time, which significantly uplifted the morale of service members in the war. The collection contains photographs, diaries, a memory book, a prayer book, certificates, newsletters, telegrams, menus, and ephemera belonging to Corporal Madeleine Coleman. Watch Six Triple Eight and then visit the Special Collections Library to meet Corporal Coleman and the extraordinary women in this collection.

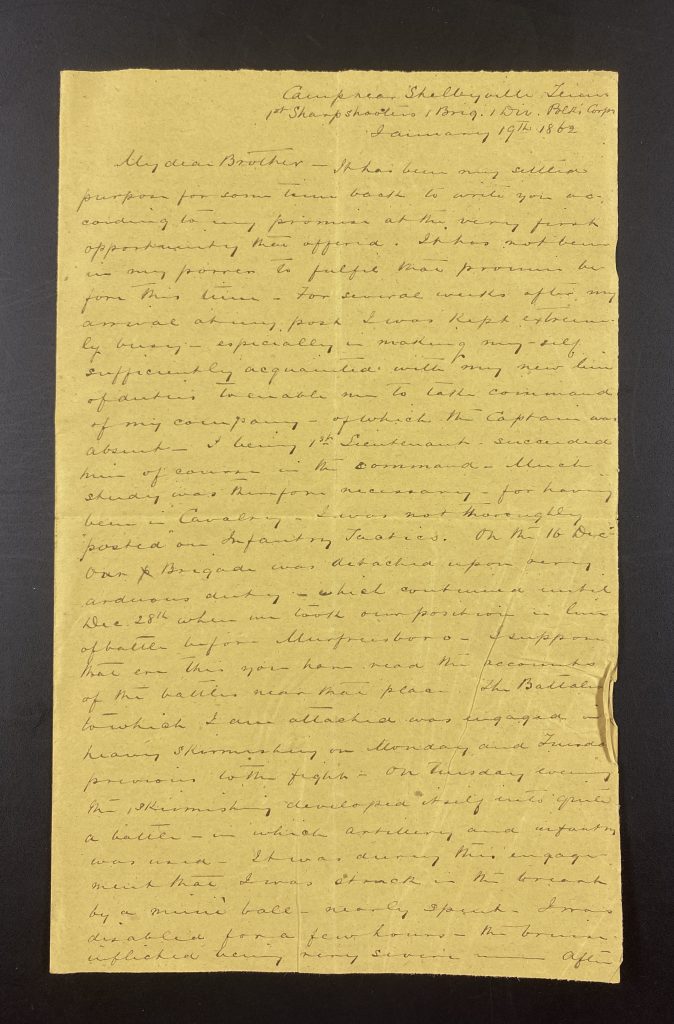

Madeleine Coleman Roach

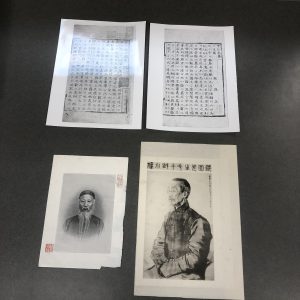

- Madeleine Coleman in her uniform. Madeleine Coleman Roach Papers (MSS 16869)

- Madeleine Coleman Roach Papers (MSS 16869)

Madeleine Coleman, originally from Milstead, Alabama, and Atlanta, Georgia, moved to New York and enlisted in the Army on January 1, 1943, following the enlistment of her boyfriend and future husband, John Roach, also from New York. She entered active service in September and was promoted to corporal, the same rank as Roach. Coleman was determined to follow him abroad and to achieve equal military rank. She trained in Fort Des Moines, Iowa; Fort Devens, Massachusetts; and Camp Sibert, Alabama, before heading overseas in 1945. John Roach trained at several locations in Texas and was also stationed overseas. They both trained as stenographers and corresponded with each other throughout the war until they married in 1946 in Roen, France.

The 6888th Battalion

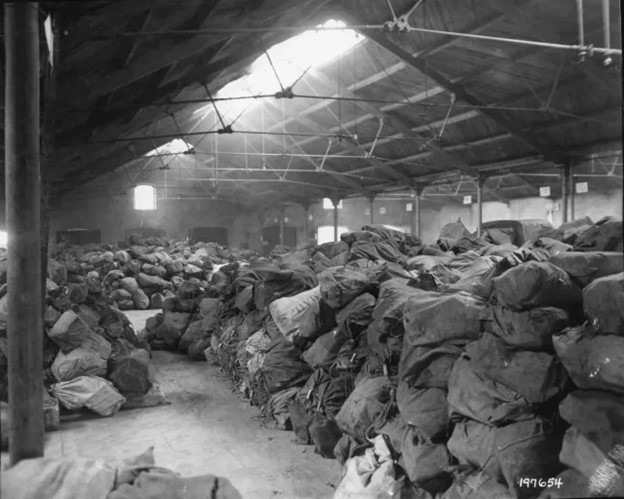

The 6888th Battalion at work. Corporal Coleman was one of 855 African American and Hispanic women (one from Puerto Rico and one from Mexico) in the 6888th who served overseas in Birmingham, England and Roen, and Paris, France. Madeleine Coleman Roach Papers (MSS 16869)

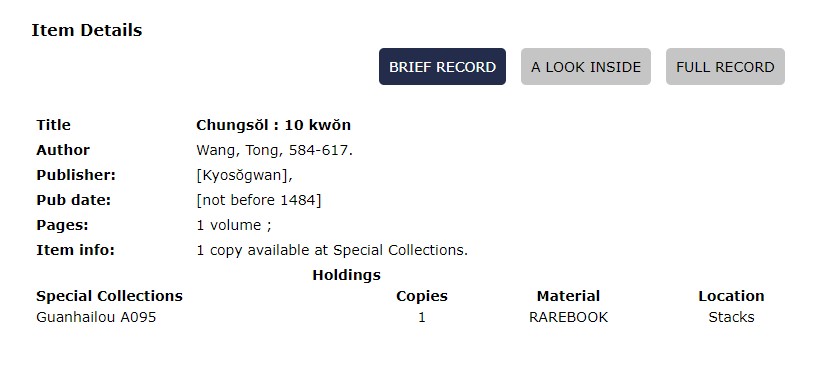

The 6888th wrote a camp newsletter entitled “Special Delivery.” Two complete issues and four partial issues are in the Madeleine Coleman Roach papers (MSS 16869).

African American women were selected from the Women’s Auxiliary Corps (WAC), the Army Service Forces, and the Army Air Forces to form the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, nicknamed “Six Triple Eight.” First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and civil rights leader Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune successfully advocated for the admittance of African American women as enlisted personnel and officers in the WAC. The response was the creation of the 6888th, a unit assigned to clear the significant backlog of mail for service members abroad. (2) General Eisenhower wanted this mail to be delivered as a means of helping with the morale of the troops. (1) Major Charity Edna Adams Early was selected to command the battalion. She was proud of the work her unit did, performing their tasks in record time. The women were trained to identify enemy aircraft, ships, and weapons and to be prepared mentally and physically for full military operations. In Birmingham, England, and in Roen and Paris, France, they found warehouses stacked to the ceilings with mailbags and rooms filled with packages of spoiled food and gifts, along with rodents. (3) The 6888th tracked individual service members by maintaining about seven million information cards, including serial numbers to distinguish different individuals with the same name. Recently recorded oral history interviews with two surviving 6888th members—Fannie Griffin McClendon and Anna Mae Robertson —provide first-person accounts of their work.

The Assignment

The assignment for the 6888th was to expedite a two-year backlog (17 million letters and packages) of mail to the seven million World War II American service members, government personnel, and Red Cross workers stationed in England and France. (2)

“Bags and bags of mail. Mission Accomplished.” Courtesy of National Archives via National Museum of United States Army.

Many pieces of mail and packages from home failed to reach service members because the military units moved quickly to new locations or because names and addresses were incomplete. Some mail had been sitting in bags for two to three years. With no encouragement or news from home, morale became very low. The 6888th Battalion sailed for two weeks from the U.S. to Glasgow, Scotland, on the ship Ile de France amidst threats from nearby German U-boats. Arriving by train in Birmingham, England, in February 1945, they worked in poorly maintained buildings such as the King Edwards School or airplane hangar warehouses, described as a “cold, dark, dirty warehouse” with broken windows, infested with rats and with mold growing on the mail. They fixed up the school and cleared the mail backlog in 90 days (half of the expected six months). They worked around the clock in three consecutive eight-hour shifts, seven days a week, and learned to become detectives searching envelopes for clues to determine the intended recipient. (3) Their filing system and efficiency made them so successful that they were asked to clear up the Army mail in Roen and Paris, France, which they did in five months. Their motto was “No Mail, Low Morale.” (2)

Discrimination

Initially the women of the 6888th recognized that the assignment was considered secondary to war efforts performed by white men and women. Despite the discrimination and racism of white officers and fellow soldiers, the women of the 6888th are now recognized for their achievement with awards, monuments, and praise. Their work is valued as being an important component of the World War II military effort. “They fired no shots, and they fought no battles … And yet, their courage and their dedication achieved a different kind of victory. Almost 80 years later, the 6888th continues to stand as a testament to the outstanding achievements of Black women Soldiers throughout U.S. Army history.” (3)

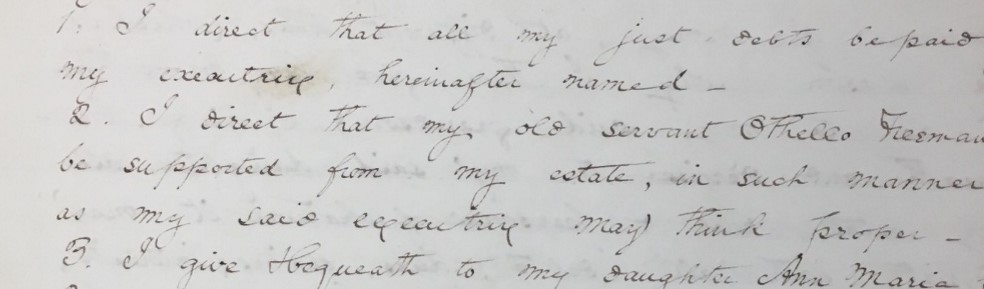

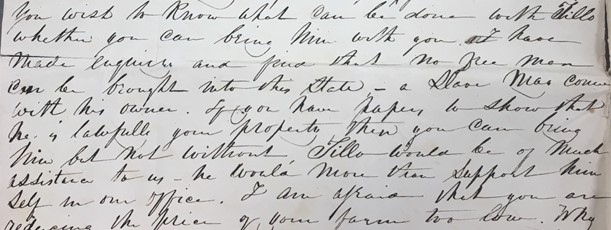

Coleman describes being forced into a segregated unit in Camp Sibert, Alabama. Madeleine Coleman Roach Papers (MSS 16869)

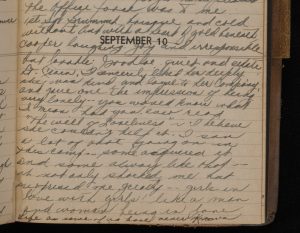

Coleman often wrote in her diary about the racial discrimination she and her fellow battalion members faced during training and from fellow Americans serving overseas. She described experiences of racism at Camp Sibert, Alabama, particularly from white women or, as she called them, “Southern crackers.” She wrote about segregation and “the appalling lack of democracy and equality in the United States.”

She also mentioned discrimination against women in the service. According to an article by Melissa Thaxton and Jennifer Dubin, “It is estimated that 150,000 women served in the WAAC/WAC during the war, about 4% of whom were African American.” Segregation practices required African American women in the Army Corps to remain at 10% of the overall force. Even after receiving full military training and extensive education for skilled positions in medicine or education, they would be placed in clerical positions or as manual laborers. While white men in America had served in military combat since the Revolutionary War, no women were allowed to enter military service until 1901 (and only then, as nurses). The military did not accept African American women until World War II—and then only in limited roles. The women in the 6888th were the first female African American unit to serve in World War II. They were successful despite the discrimination they faced. In 2022 they were recognized for their service with the Congressional Gold Medal “…not only for their successful completion of their mission at the end of World War II, but for their sustained collective pursuit of racial and sex equality in the face of significant social and political barriers.” (3)

Retired Colonel Edna W. Cummings declared, “The Congressional Gold Medal is the nation’s gratitude for the 6888th Battalion and the thousands of African American women who served in the Army during World War II. Their service will never be forgotten as soldiers and trailblazers for gender and racial equality.” (3)

Alyce Dixon, a former corporal in the 6888th expressed her feelings about her service, “We’re all human — whether Black, white, red or brown, and we all have something to offer.” (3)

Elaine Bennett explained that she joined the WAC “because I wanted to prove to myself, and maybe to the world, that we [African Americans] would give what we had back to the United States as a confirmation that we were full-fledged citizens.” These pioneer women who had limited opportunities for employment at home sought a life of adventure and patriotism amidst adversity and made a difference in the world. (3)

Madeleine Coleman’s Diary

Corporal Coleman had an active social life at dances at the service club. Madeleine Coleman Roach Papers (MSS 16869)

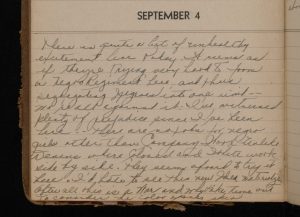

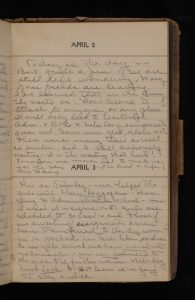

Coleman’s diary, written before her service overseas, features excerpts from her daily life of training, marching, drilling, and working in the office and field in the Army from 1943-1944. She wrote about her exhaustion from work, her anxieties about army inspections, and her private thoughts on the harsh treatment against African Americans and women in the Corps, especially at Camp Sibert, Alabama. She often encouraged herself with positive messages, such as “what’s next for you little girl.” She also described her social experiences, with dates and dances at the service club. Her diary entries reflect her commitment to John Roach while she compares him with other men that she dated.

- Pages in Coleman’s diary about her daily work and school schedule. Madeleine Coleman Roach Papers (MSS 16869)

- Diary entry: “I lived a lifetime today.” Madeleine Coleman Roach Papers (MSS 16869)

Of interest are diary entries which exhibit straightforward curiosity when she learned about women in lesbian relationships for the first time.

Coleman describes her surprise that her friend is a lesbian. Madeleine Coleman Roach Papers (MSS 16869)

Photographs

There are about 35 photos in the collection depicting Coleman’s service and showing women in uniform, many in Rouen and at the French Riviera. Included is a photograph of her commanding officer, Major Charity Adams Early, who was a popular leader and one of the highest-ranking African American female officers in the nation. There are also documents of John Roach’s military service in Texas, Italy, and Army bases in the South Pacific.

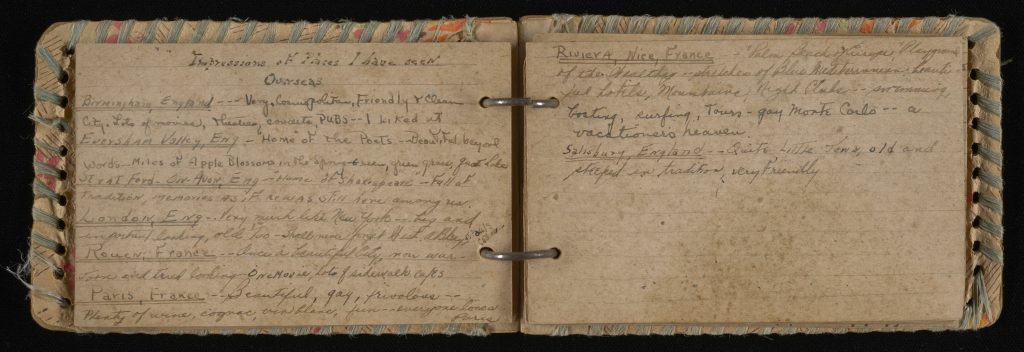

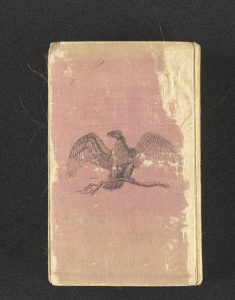

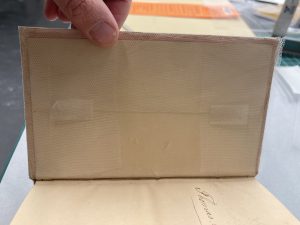

Coleman’s “Memory Book” highlights the various places she lived and worked during the war. It includes signatures and messages from fellow soldiers. Madeleine Coleman Roach Papers (MSS 16869)

After the War

Sailing home. Madeleine Coleman Roach Papers (MSS 16869)

After the war, Madeleine Coleman Roach became a secretary at the Woodrow Wilson Vocational School (August Martin High School) in New York City. She graduated from York College with honors in African American Studies in the early 1980s. Part of the college library is named for her. John Roach was employed with the postal service. They had two daughters, Rouena and Phoebe, and lived in South Ozone Park, New York. Madeleine Roach died in 1984 at the age of 65 following the death of her beloved husband, John Roach, in 1983.

With an origin story that started with discrimination and segregation as part of the WAC, the 6888th was a precursor to the Civil Rights movement in America.

“The Six Triple Eight’s achievements are remarkable considering the fraught social and political climate of the time. Indeed, the women of the 6888th Postal Directory Battalion proved to be pioneers in military service during an era when racial segregation was law, and few opportunities were available to women to work outside the domestic sphere.” (3)

The current celebration of the 6888th Battalion in films and documentaries as well as in books and archives is well-deserved and long overdue.

Sources

- Chamberlain, J. “African American Women in the Military During World War II” Posted in African American History, Films, Military, Motion Pictures, U. S. Army. The Unwritten Record. National Archives. 12 March, 2020. https://unwritten-record.blogs.archives.gov/2020/03/12/african-american-women-in-the-military-during-wwii/

- Fargey, Kathleen. “Women of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion” 14 February, 2014. Buffalo Soldier Educational and Historical Committee. Accessed 3/21/25. https://www.womenofthe6888th.org/the-6888th

- Thaxton, Melissa and Dubina, Jennifer. “A Different Kind of Victory: The 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion.” National Museum of United States Army. Accessed 3/21/25. https://www.thenmusa.org/articles/a-different-kind-of-victory-the-6888th-central-postal-directory-battalion/

For More Information

Rose, Naeisha. “Remembering a 6888 Veteran”. Queens Chronicle. Queens New York. 13 February 2025. Accessed 2/25/25

https://www.qchron.com/editions/queenswide/remembering-a-6888-veteran/article_0ef47078-4275-5df5-ae74-4fb5f9c1e9f3.html

Lauria-Blum, Julia. “No Mail, Low Morale, The Six-Triple-Eight Delivered” Metropolitan Airport News. 1 February 2025. “No Mail, Low Morale” The Six-Triple-Eight Delivered!

Perry, Tyler, “Triple Six Eight: Everything you need to know. Tudum by Netflix. Accessed 3/17/2025 https://www.netflix.com/tudum/articles/tyler-perry-new-netflix-movie-six-triple-eight

![March 17 and 18 diary entries with “Work[,] school[,] dull" written for each day.](https://smallnotes.library.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/000060287_0002-193x300.jpg)

![Fourth page of a handwritten letter, containing two notes: first, “Miriam” [middle daughter?] to “Dear father" dated March 7th, 1865; the second, from “Rosa” [youngest daughter?] to “my dear father.”](https://smallnotes.library.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/000059429_0004.jpg)

![Letter from William, who drove the carriage for Mr. Chalmers, to Anna Maria Mead Chalmers after Mr. Chalmers’s death. May 2, [1875]](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/William.jpg)