Small Special Collections Library Manuscript and Archives Processor Ellen Welch is back with another story from her work to process the papers of Anna Maria Hickman Otis Mead Chalmers (1809-1891):

It has been very exciting to process this collection and learn of an enslaved person called Othello “Tillo” Freeman. Anna Maria Hickman’s grandfather, General William Hull, who served in the American Revolutionary War and was governor of Michigan, enslaved Othello Tillo Freeman—and “Tillo” is mentioned in legal documents and in the family correspondence. Othello Freeman, if that is even his real name, is represented in the collection by the perspectives and bias of the family. They characterize their relationship with Tillo as being someone that they needed to take care of instead of recognizing that he should be a free man (1. Historic Newton). The collection was part of our backlog of holdings that are open but needed a higher level of processing to give more visibility and description of marginalized persons in the collection. Thanks to our curator, Molly Schwartzburg, for facilitating an addition to the Mead Chalmers family papers which led to the rediscovery of this historic collection that documents the stories of enslaved people and the generations of the Hull family. They lived in Michigan, Massachusetts and Virginia during epic moments in our history from 1821 to 1897. The collection contains nineteenth century correspondence that would be relevant to historians and scholars because it reveals the complicated relationships of enslavement, including letters about Othello Freeman, as well as a letter written by a formerly enslaved person, William.

Content warning: the collection does contain offensive language.

The papers of Anna Maria (Campbell Hickman) Otis Mead Chalmers (1809-1891 (MSS 4966) and her family offer a deep look into a 19th century American family with a sharp focus on enslaved and formerly enslaved persons. The collection documents the life of a young, widowed woman, Anna Maria Mead Chalmers, who was the granddaughter of General William Hull (1753-1825). She was a mother of four children and became a businesswoman in Richmond, Virginia. She was a writer, an editor of the Southern Churchmen, an educator and founder of Mrs. Mead’s School for Young Ladies, and a director of The Southern Churchmen Cot (“Retreat for the Sick”), a hospital for children. Anna Maria’s family enslaved people who are mentioned in the papers, including Othello “Tillo” Freeman (1790’s-1860’s?).

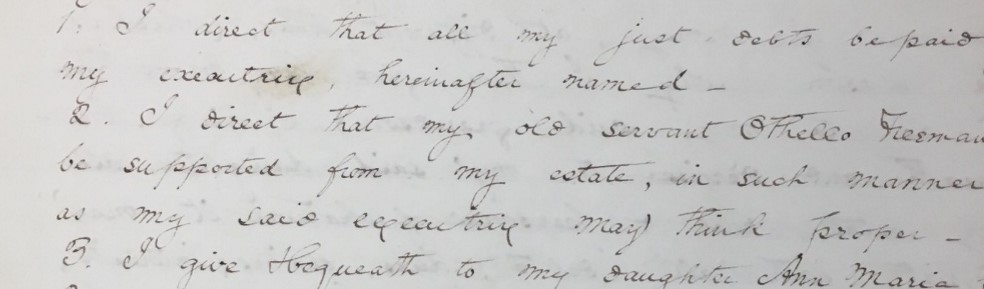

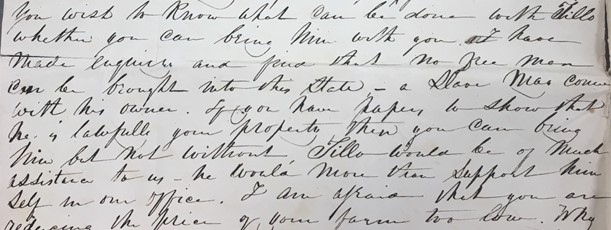

In the correspondence of the Mead-Chalmers family are letters describing Othello “Tillo” Freeman. According to the History of Newton Massachusetts, Town and City, From Its Earliest Settlement to Present Time 1630-1880 by Samuel Francis Smith, Tillo was the last known enslaved person in Newton, Massachusetts (2 Smith, S. F.). When Tillo could not work anymore, Anna Maria’s mother, Nancy “Ann” Binney Hull Hickman (1787-1847) left a stipulation in her will that his housing, clothing, and medical care would be provided for him. At the time, this would have been considered generous but there was no discussion of granting him his freedom from enslavement. Instead, the family also inquired about slave laws for travelling with the family so that they could bring Tillo with them when they moved from Newton, Massachusetts to Richmond, Virginia.

Nancy Ann Binney Hickman last will and testament (September 16, 1846) making provisions for the care of Othello “Tillo” Freeman

Letter from Zachariah Mead to his mother-in-law Nancy Ann Binney Hickman explaining that if she moves to Virginia from Massachusetts that she will need to have legal papers to bring Tillo with her. (August 24, 1838)

Letters in the collection show that the Mead and Chalmers family describe themselves as being anti-slavery but not supportive of abolition. They believed in educating enslaved persons but did not free them because they felt that the enslaved needed the protection of their white enslavers.

Anna Maria Mead Chalmers recounts memories of living with her grandparents, General William Hull and Sarah Fuller Hull, in Newton, Massachusetts and describes their first meeting of an African American named Sam. He survived being enslaved and beaten in Louisiana and escaped to the Hull farm where he was given rest and, after he recovered, worked on their hay fields for the rest of his life. Anna Maria Chalmers refers to him as a “hired” [African American] working on the farm. Her recollection focuses on the kindness that her grandmother bestowed upon Sam who stayed on the farm until his death thirty years later. He was called “Sam the fiddler” because he played the fiddle for the children. He is characterized as faithful and loyal, and while he may have felt gratitude, this description does not take into consideration that he never had the opportunities that existed for free white men.

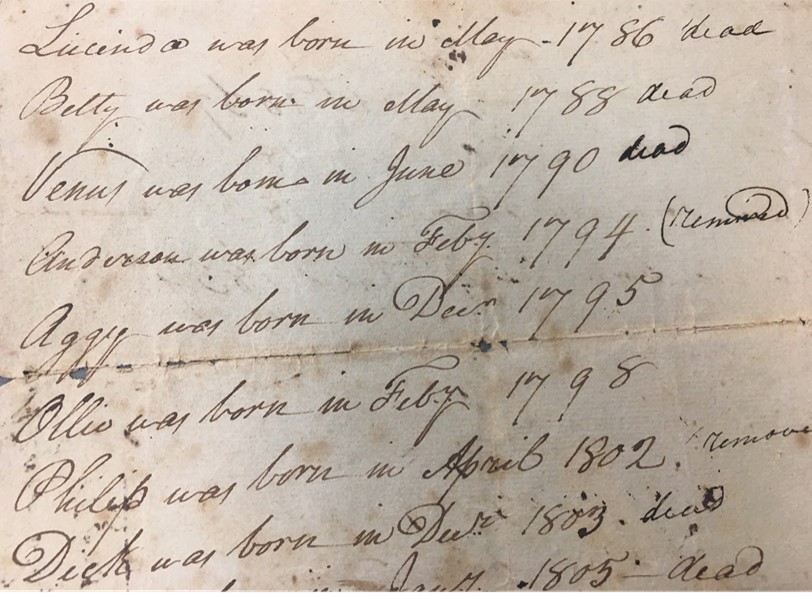

There is also a leather-bound account book containing a list of the first names of enslaved persons. It is not clear who owned the book or the location of the enslaved persons, but the list is extensive and dates from 1767 to 1845. Also included in the account book are records for horses and business transactions.

Another formerly enslaved person, William, wrote a letter to Mrs. Chalmers (May 2, 1875) in which he expresses sorrow for the death of her husband, David Chalmers. The letter appears to express the mutual affection shared between Mr. and Mrs. Chalmers and William. It offers a rare glimpse into the realities that people experienced in the institution of enslavement, showing that as wrong as it is to own a person, there are a range of emotions that are hard to describe when people are living close together, with their relationships intertwined in daily life. According to the context provided in these family letters, the family acted as benevolent providers by teaching enslaved persons to read the Bible, paying for their bedding, clothing, medical care, rest, and retirement if they could not work. The family and the formerly enslaved person express intimacy and concern for one another as people might do when they live close together, but at the same time, they are forcing them to serve in bondage or limiting their freedom by offering them work with very low wages. Even though the language in the correspondence appears to be caring and intimate, it must be noted that enslaved persons had no choice in the relationship and that only the family perspectives are fully represented.

![Letter from William, who drove the carriage for Mr. Chalmers, to Anna Maria Mead Chalmers after Mr. Chalmers’s death. May 2, [1875]](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/William.jpg)

Letter from William, who drove the carriage for Mr. Chalmers, to Anna Maria Mead Chalmers after Mr. Chalmers’s death. May 2, [1875]

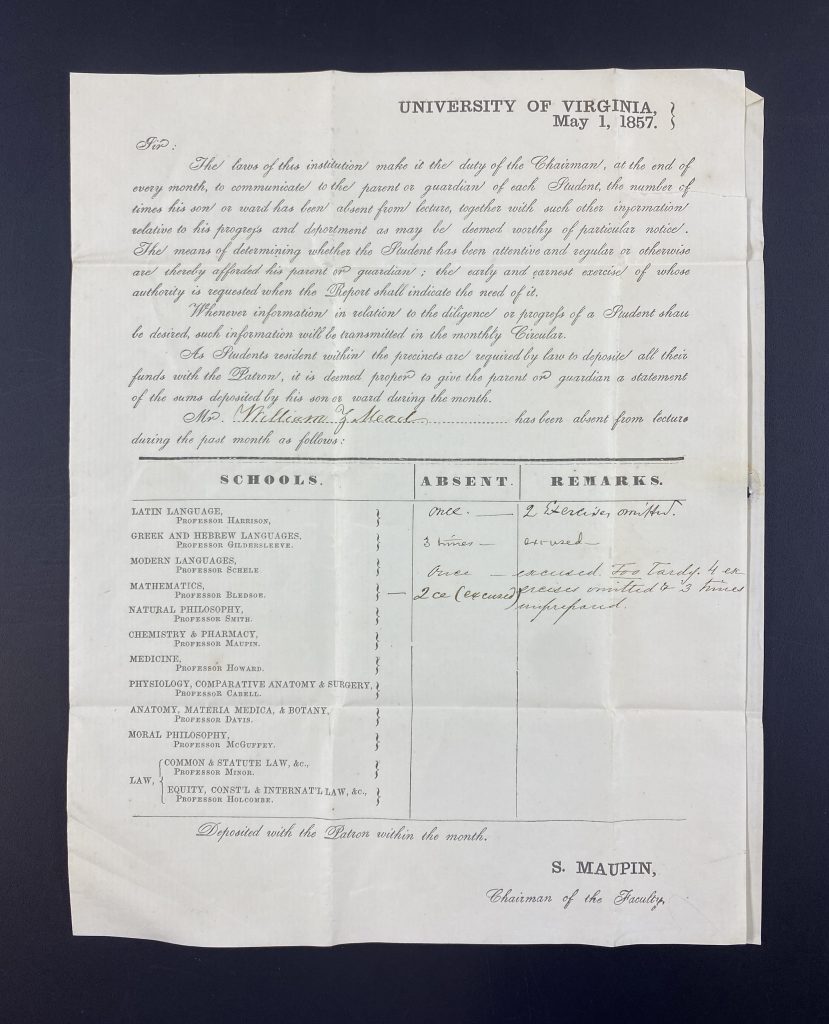

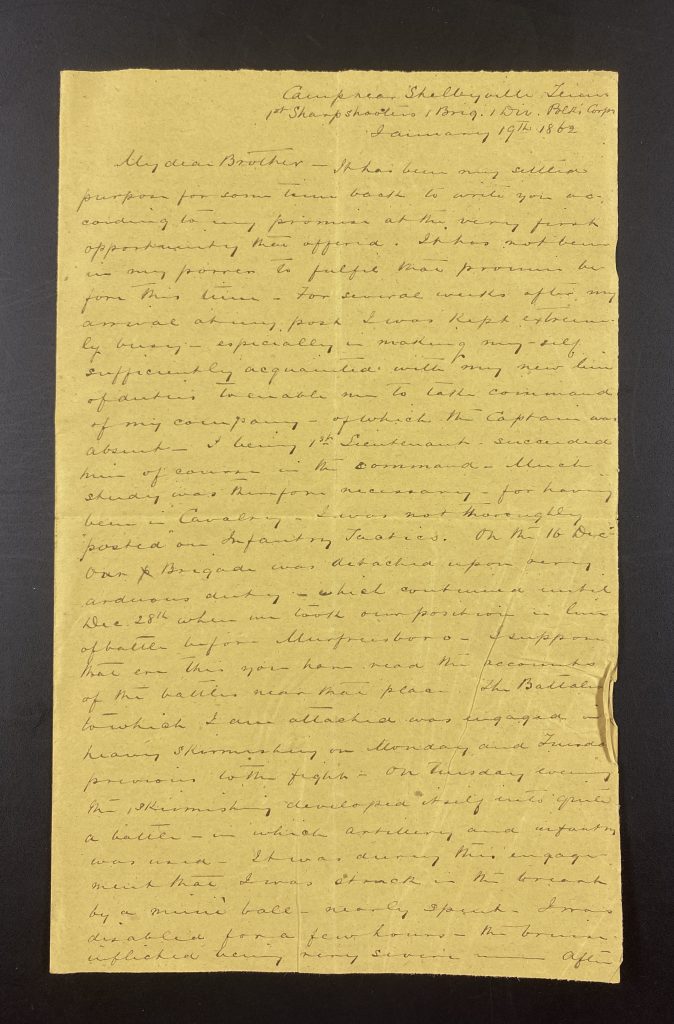

Letter from Lieutenant William Mead describing the Battle of Murfreesboro where he was injured. (January 19, 1862)

William Mead graduated from the University of Virginia in 1857 before the Civil War began. The collection has many references to Charlottesville and the University of Virginia, including comments about university professors Basil L. Gildersleeve, Gessner Harrison, Socrates Maupin, John Minor, Schele De Vere, James L. Cabell, Frederick George Holmes, and Alfred T. Bledsoe. Charlottesville families include Peter and Frances (“Fannie”) Meriwether, Frances Poindexter, Rector, and Mrs. Ebenezer Boyd, William Cabell Rives, Franklin Minor, Thomas Walker Gilmer and Elizabeth Anderson Gilmer, and Dr. Mann Page.

Anna Maria Otis Mead Chalmers was extraordinary in having been as well educated as any man in Boston (3 Duval, Maria Pendleton) and shared her knowledge with other privileged young white girls, including Amélie Rives Troubetzkoy, the famous writer. She and some of her family members were friends with literary authors including Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel P. Willis, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Oliver Wendell Holmes. The letters refer to these writers, but there are no letters written by or to the authors themselves.

The collection also includes correspondence from Anna Maria Mead Chalmer’s cousins, James Freeman Clarke (1810-1888) and his sister, Sarah Freeman Clarke (1808-1896). Sarah Clarke was a landscape artist, a world traveler, and a member of the transcendentalist movement (4 Maas, Judith). James Clarke was an American theologian, author, and abolitionist (5 Wikipedia).

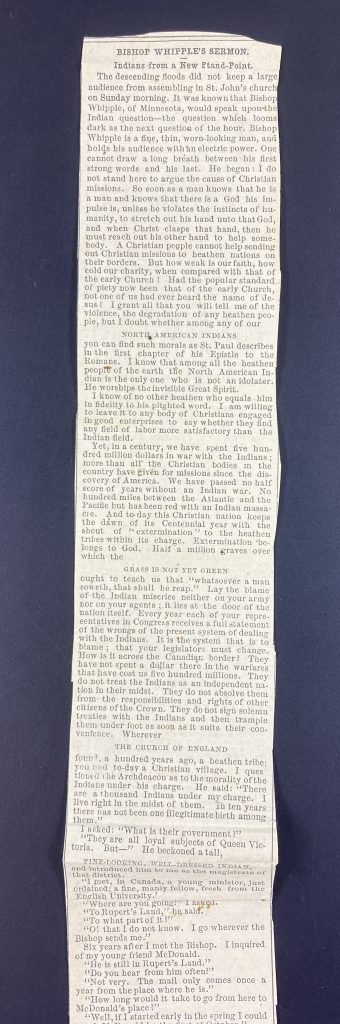

Also of interest in the collection are letters about General William Hull (1753-1825) who fought in the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. He was born in Derby, Connecticut and moved to Detroit Michigan when his government work, which involved the taking of land from Indigenous persons, led him to become the Governor of the Territory of Michigan and the commander of the Army of the Northwest Territory during the War of 1812. He was appointed by Thomas Jefferson and was a friend of General Lafayette. After being unsuccessful in fighting off the Canadians (however claiming that the government did not give him the resources to defend Michigan) he was court-martialed by James Madison who later commuted his sentence (6 Detroit Historical Society). For years, the family fought a claim to refute the charges and receive his backpay. In contrast to General Hull’s work with the government in taking land from Indigenous people, the family kept a newspaper clipping of a sermon by Bishop Henry Benjamin Whipple (1822-1901) printed in 1876 which displays Whipple’s outrage at the United States government for taking lands from Indigenous persons.

Covering a wide-range of historic themes, including: the taking of Indigenous lands; enslavement of African Americans; the story of a widowed woman trying to earn a living in the nineteenth century; the War of 1812 and the American Civil War; as well as politics, religion, transcendentalism, local Charlottesville history and professors at the University of Virginia—this is a collection of letters rich in history that shows the inner workings of government and society, and how those systems impact people’s everyday life. Collections like the Papers of Anna Maria (Campbell Hickman) Otis Mead Chalmers (1809-1891) help us to envision our collective past and broaden our perspective on our history and our future. This one is worth a deep dive into the history of the nineteenth century locally and nationally.

Sources:

- Historic Newton, Historic Burying Grounds Preservation

Attachments F-1 – F3 for Historic Resource Proposals - Smith, S. F. History of Newton Massachusetts. Town and City. From Its Earliest Settlement to Present Time 1630-1880.” Boston: The American Logotype Company, 1880.

- Duval, Maria Pendleton. “The Lengthened Shadow of a Woman” in The Richmond Times Dispatch. August 10, 1913 (Description of Anna Maria Mead Chalmers education in William B. Fowle’s school as being the best in Boston and Mrs. Chalmer’s school as being up to the standards of Harvard)

- Maas, Judith. “Sarah Freeman Clarke: Artist, Traveler, Diarist” The Beehive. Massachusetts Historical Society. November 21, 2019

- “James Freeman Clarke.” Wikipedia. Accessed June 7, 2022.

- “William Hull” Detroit Historical Society. Detroit Encyclopedia. Accessed June 7, 2022.

Other articles of interest:

Martin, Susan. “The Unstoppable Anna Maria Mead Chalmers,” The Beehive. Massachusetts Historical Society. June 7, 2022.