By: Sue Donovan, Conservator for Special Collections

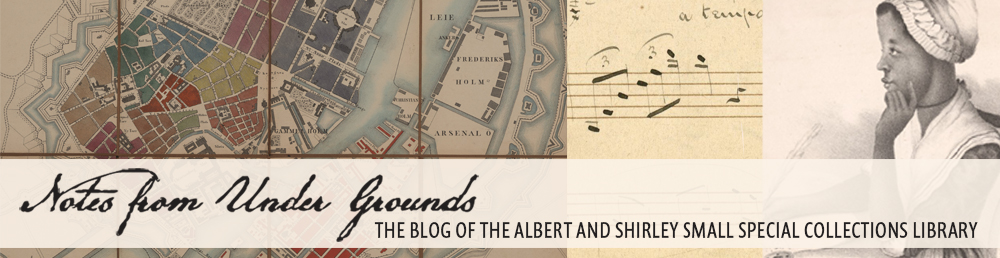

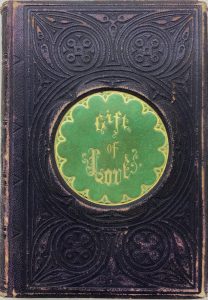

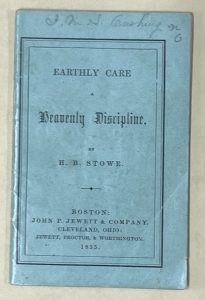

A wonderful opportunity for collaboration took place recently in Shannon Library’s Special Collections Conservation Lab. As part of our Orange Flag Workflow, or the process by which rare book catalogers and archivists alert us to preservation issues, a book entitled The Zoological Keepsake came to my bench. Published in 1830 in London, the book had its original boards which were covered in silk. It was purchased as part of the History of Childhood collection, and it is described as “a child’s miscellany of facts, literature, and prose on animals” (from The National Library of Australia’s catalog). The cataloger had flagged it because the silk was quite damaged and even missing in some parts. I had never worked with a book bound in silk before, so I knew it was time to reach out to a colleague in textile conservation, Claudia Walpole.

- Before Treatment of The Zoological Keepsake, front cover.

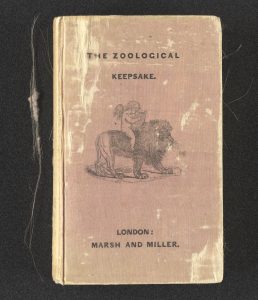

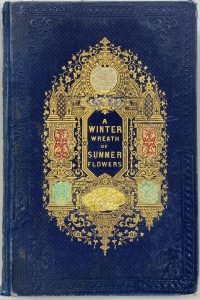

- Before Treatment of The Zoological Keepsake, back cover.

Claudia cautioned against using any kind of adhesive to reattach or stabilize the silk since it could cause discoloration of the silk. Instead, she suggested using bobbinet tulle (“bobbinet” is the term for tulle that is machine-made in the UK) sewn around the book. Since any covering would have to be made to allow the boards to open independently, the first thought that came to my mind was to use the bobbinet like a dust jacket wrapper. The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library has one of the largest collections of dust jackets, so I am familiar with the kinds of wrappers that go around brittle paper, but I couldn’t use the same kind of wrapper with The Zoological Keepsake because it would create static that could damage the silk further.

Creating a wrapper with bobbinet in the style of a dust jacket wrapper seemed to have potential, so I set to work experimenting with how to adapt a conservation textile to library and archives conservation.

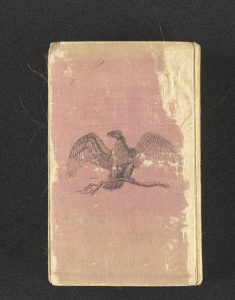

Nylon bobbinet was smooth and blended in well with the original silk, and I found out that I could weld two pieces together on the ultrasonic encapsulator, a piece of equipment that we use frequently to make reversible plastic enclosures for unbound sheets of paper, drawings, and maps.

I molded nylon bobbinet around the book cover by welding a top seam with the encapsulator and using a heated spatula to create a crisply-creased bottom seam.

- Image of nylon bobbinet placed on top of a green cutting mat where each square is ½ inch.

- The welded edge of two pieces of nylon bobbinet.

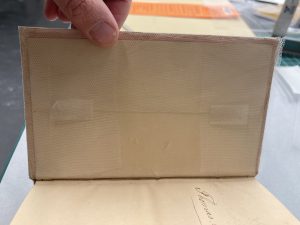

Then I needed to fold a flap of the wrapper around each board to keep the wrapper in place. I experimented with using heat alone to attach the nylon to itself, but all my attempts failed, so I ended up using strips of heat-activated mending paper to tack the side flaps to the top and bottom flaps to hold everything in place.

Inside the front board of The Zoological Keepsake, showing the heat-activated mending paper.

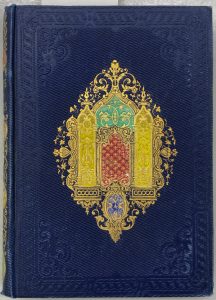

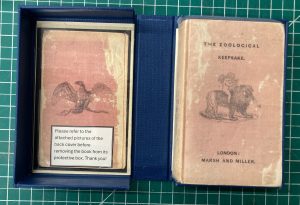

Once in place, the bobbinet does a good job of protecting the original silk of the binding. All of the damaged silk is enclosed and protected from further damage. However, the bobbinet does make the book feel more slippery in the hands, so I thought it would be better to limit handling by placing the book itself in a drop-spine box.

I made a custom box for the volume and included an image of the verso of the book inside the box itself so that anyone curious about the back wouldn’t have to handle the book to see the design.

Image of The Zoological Keepsake shown inside a drop-spine box with the bobbinet wrapper in place.

Overall, this was a great project to work on. It involved collaboration with a conservator in a different field and the adoption of a little-used material in library and archives conservation. I am pleased with the result, and I learned a lot! Two conservators have already reached out to me about the material and the process, so I think it will be helpful to other conservators if they encounter a similar item in the future.