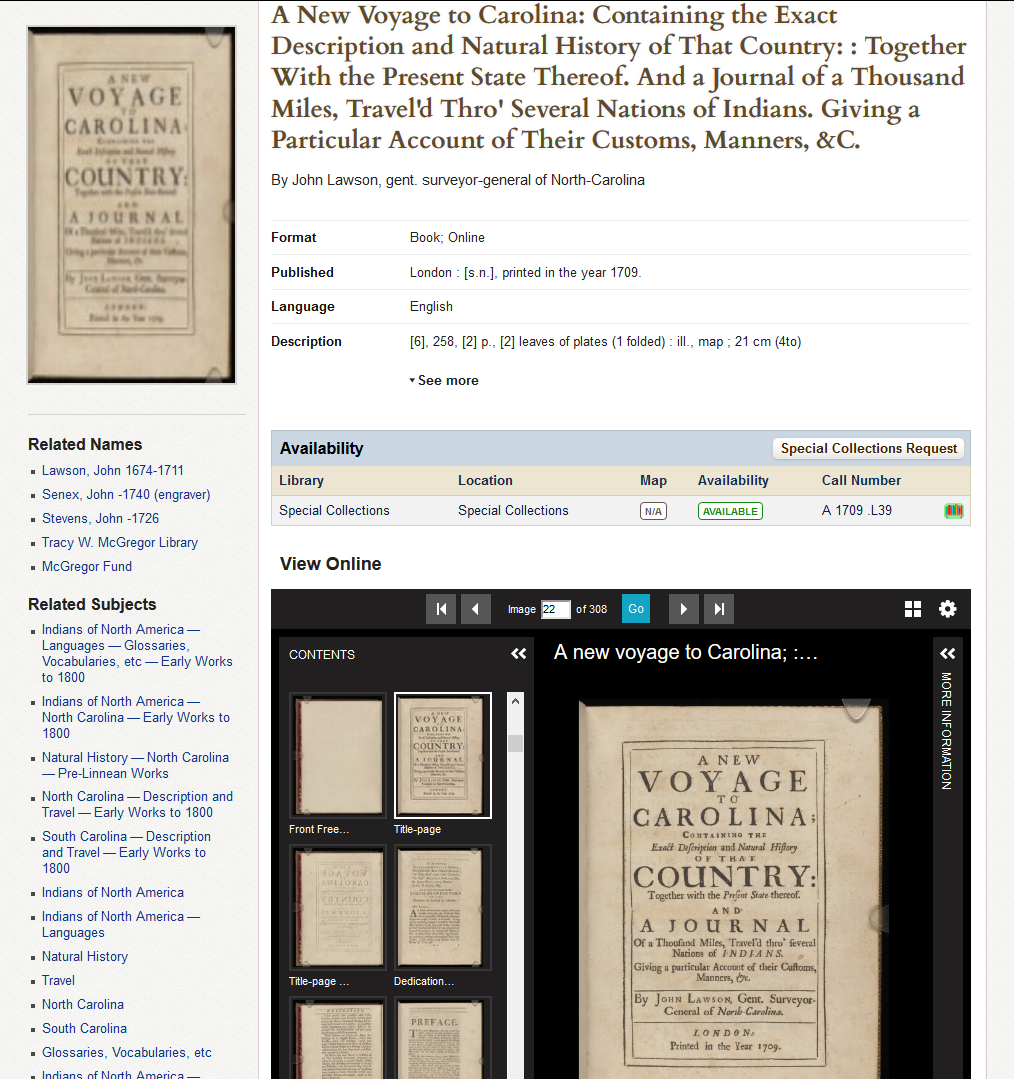

On November 5 high-resolution scans of John Lawson’s A New Voyage to Carolina (London, 1709) were added to the U.Va. Library’s digital repository and made publicly accessible through Virgo, the Library’s online catalog. This brought to a successful close our six-year effort to improve access to the world-renowned Tracy W. McGregor Library of American History.

First, some background. On the day that Alderman Library was dedicated in June 1938, U.Va. received a truly transformational gift: the Tracy W. McGregor Library of American History. Initially formed by Detroit philanthropist Tracy W. McGregor, the McGregor Library was then, and remains, one of the nation’s foremost collections of rare books documenting the discovery and settlement of the New World, and the pre-1900 history of North America and the United States.

Since 1938 the McGregor Fund of Detroit, Mich., has partnered with the U.Va. Library to provide for the superb library collected by its founder, Tracy W. McGregor. The McGregor Fund’s first benefaction was the magnificent McGregor Room in Alderman Library, built expressly to house the McGregor Library and to serve as a Special Collections reading room. Other major McGregor Fund gifts have included the recent McGregor Room renovation; a substantial acquisitions endowment for the McGregor Library, which has quintupled in size since 1938; a series of publications based on the collection; and the annual Tracy W. and Katherine W. McGregor Distinguished Lecture in American History.

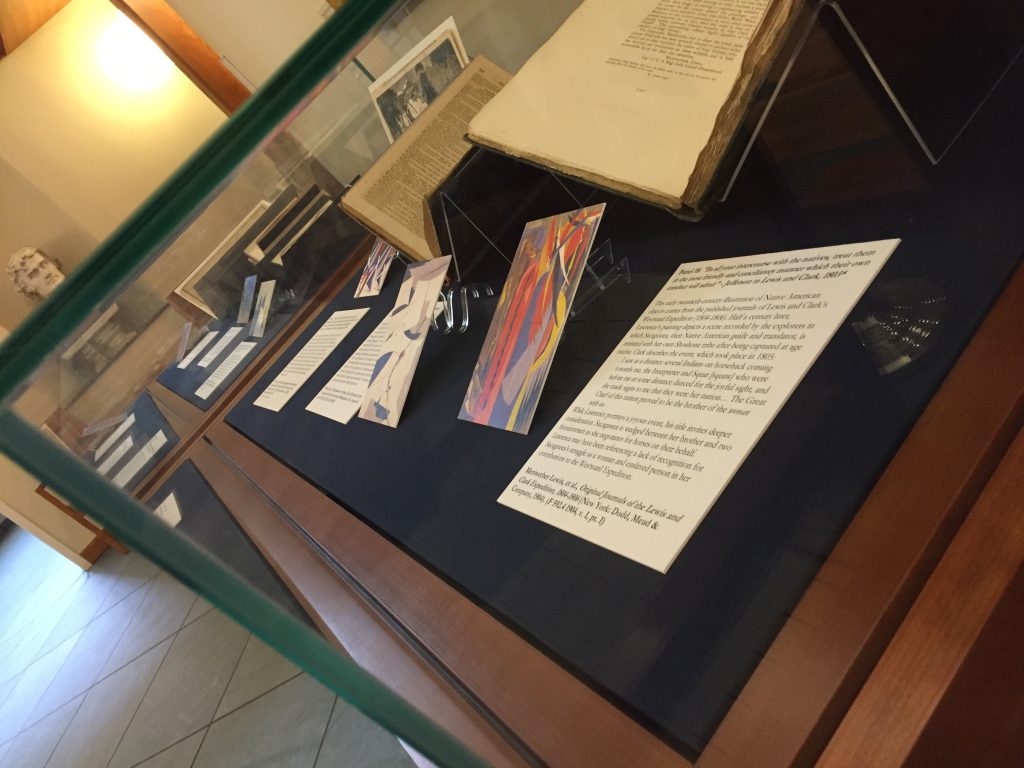

In 2013 the McGregor Fund offered to finance a major initiative to expand public access to the McGregor Library. We proposed a two-pronged approach involving the rarest and most significant works in the 20,000-volume McGregor Library: 1) prepare and make freely accessible online high-resolution digital images of these works, and 2) improve their discoverability in Virgo and other bibliographical databases by upgrading their catalog records. The McGregor Fund generously provided an initial grant of $245,000, awarding an additional $70,000 in 2017 so that we could expand the project’s scope.

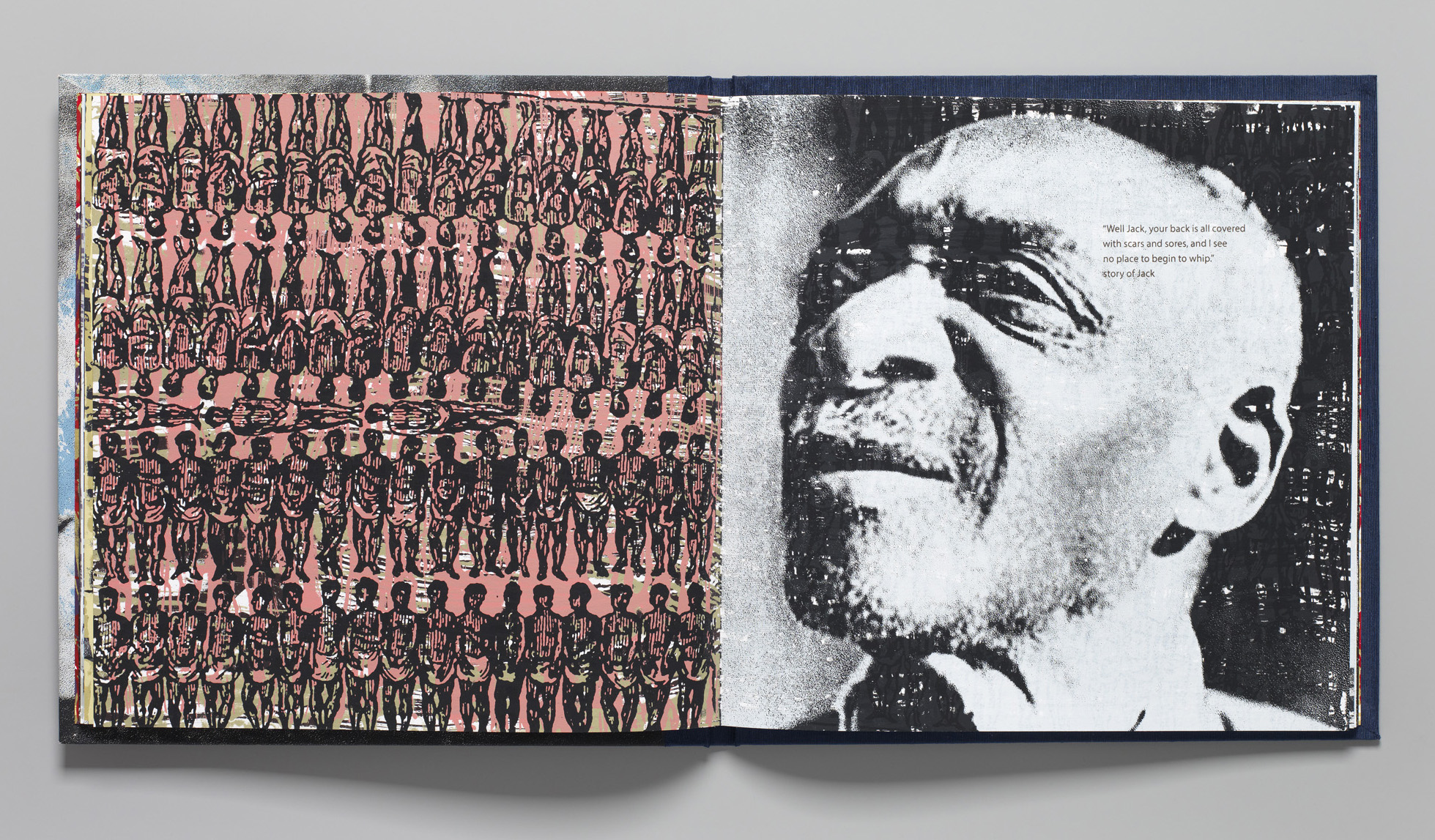

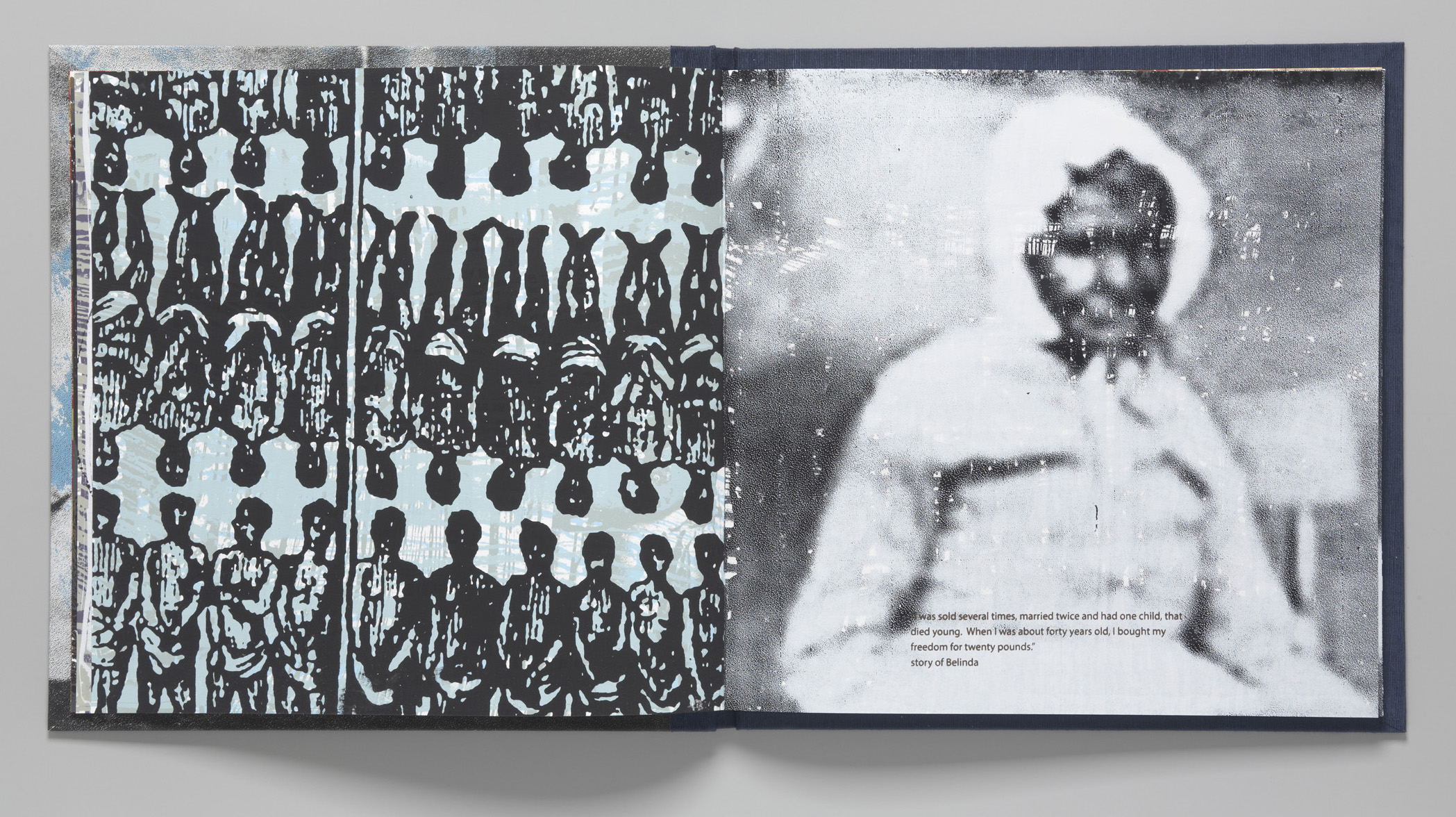

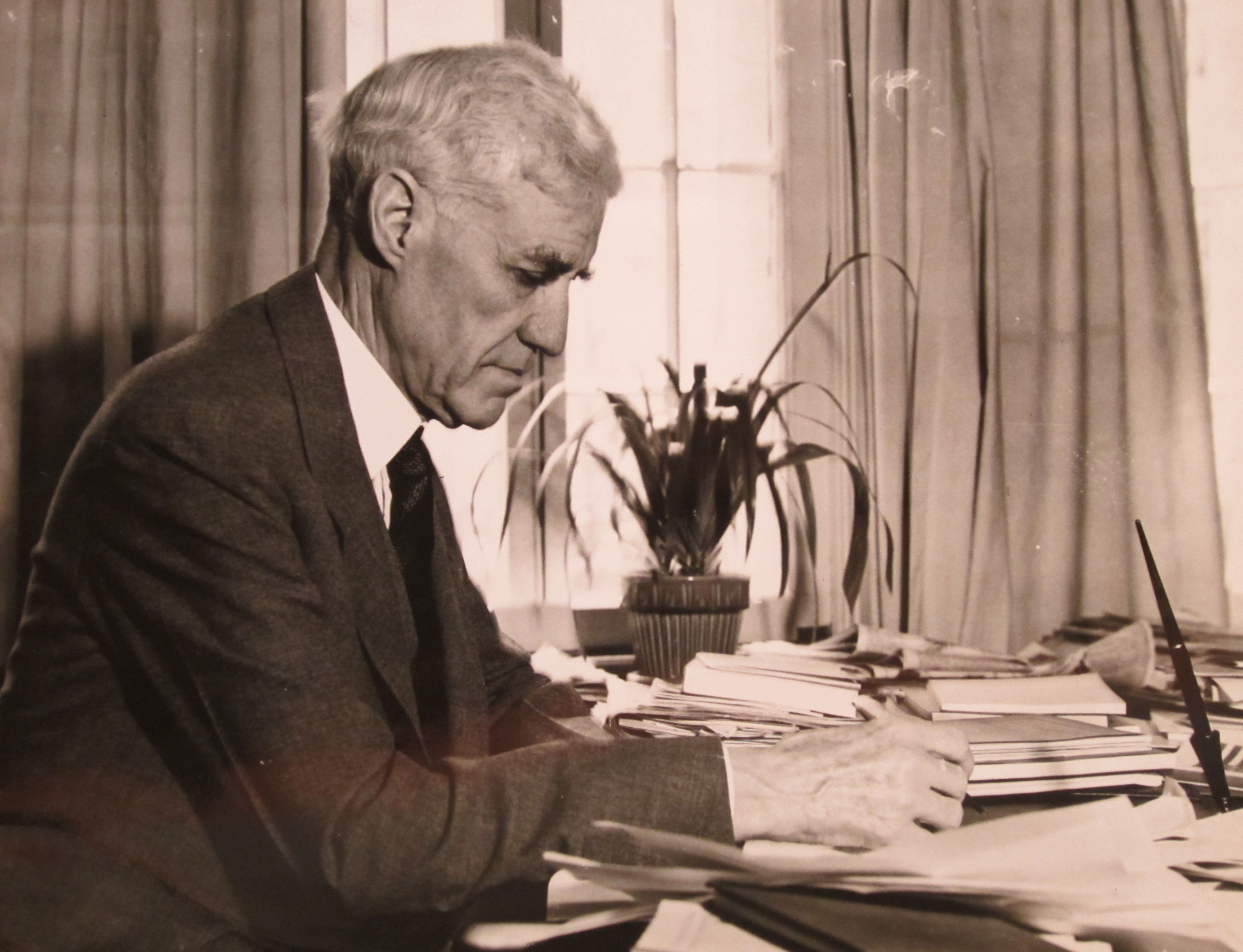

Key members of Team McGregor include: Sam Pierceall, Imaging Specialist and Project Coordinator; Adam Newman, student supervisor; and Christina Deane, Manager, Digital Production Group (photo by Eze Amos)

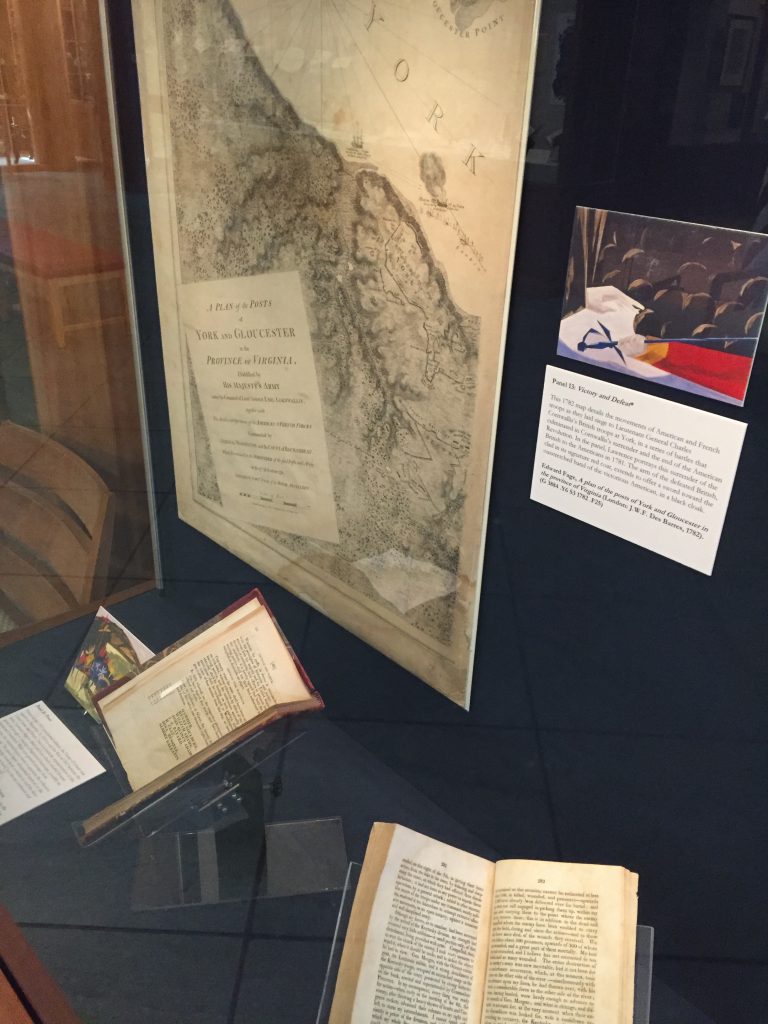

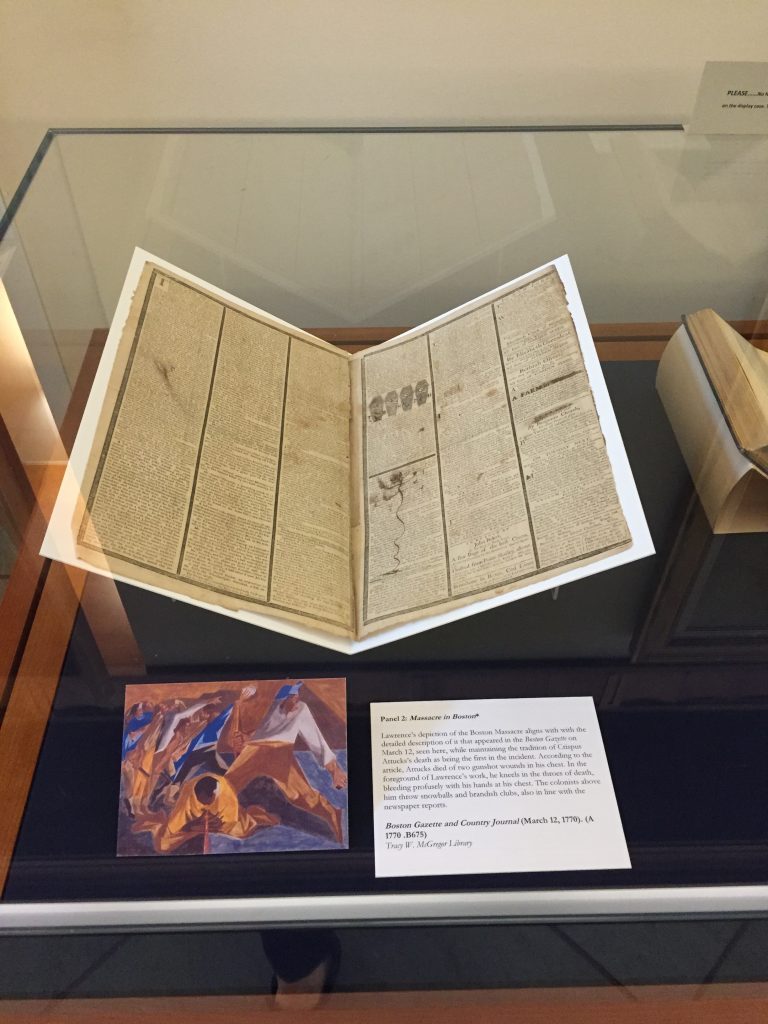

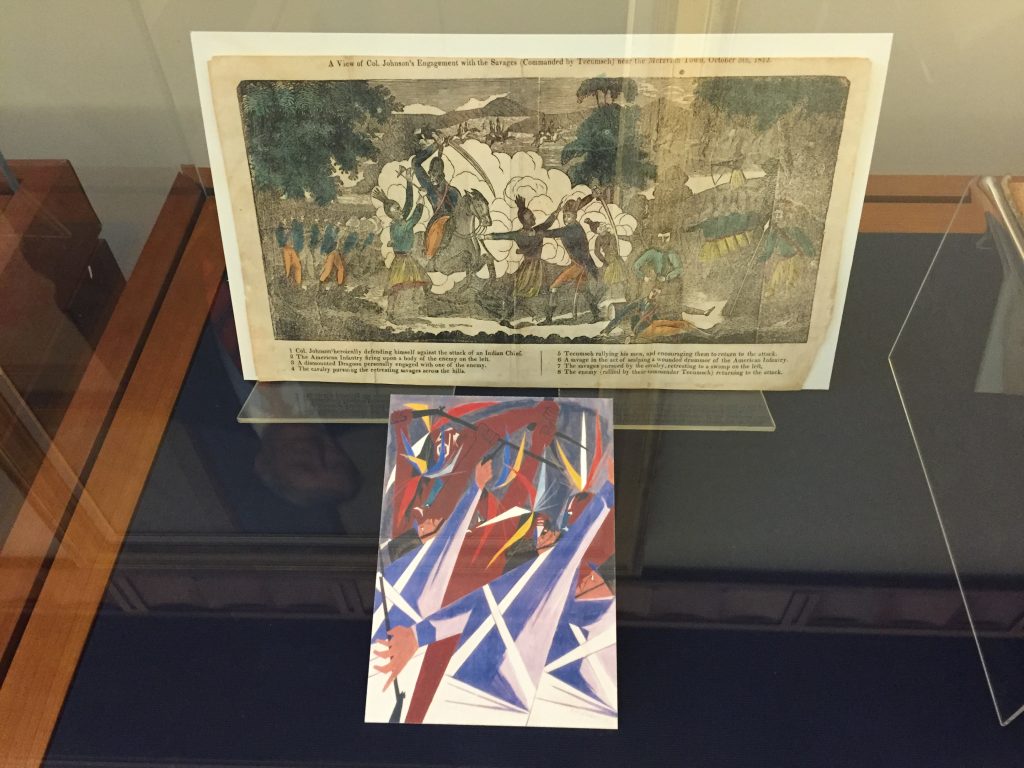

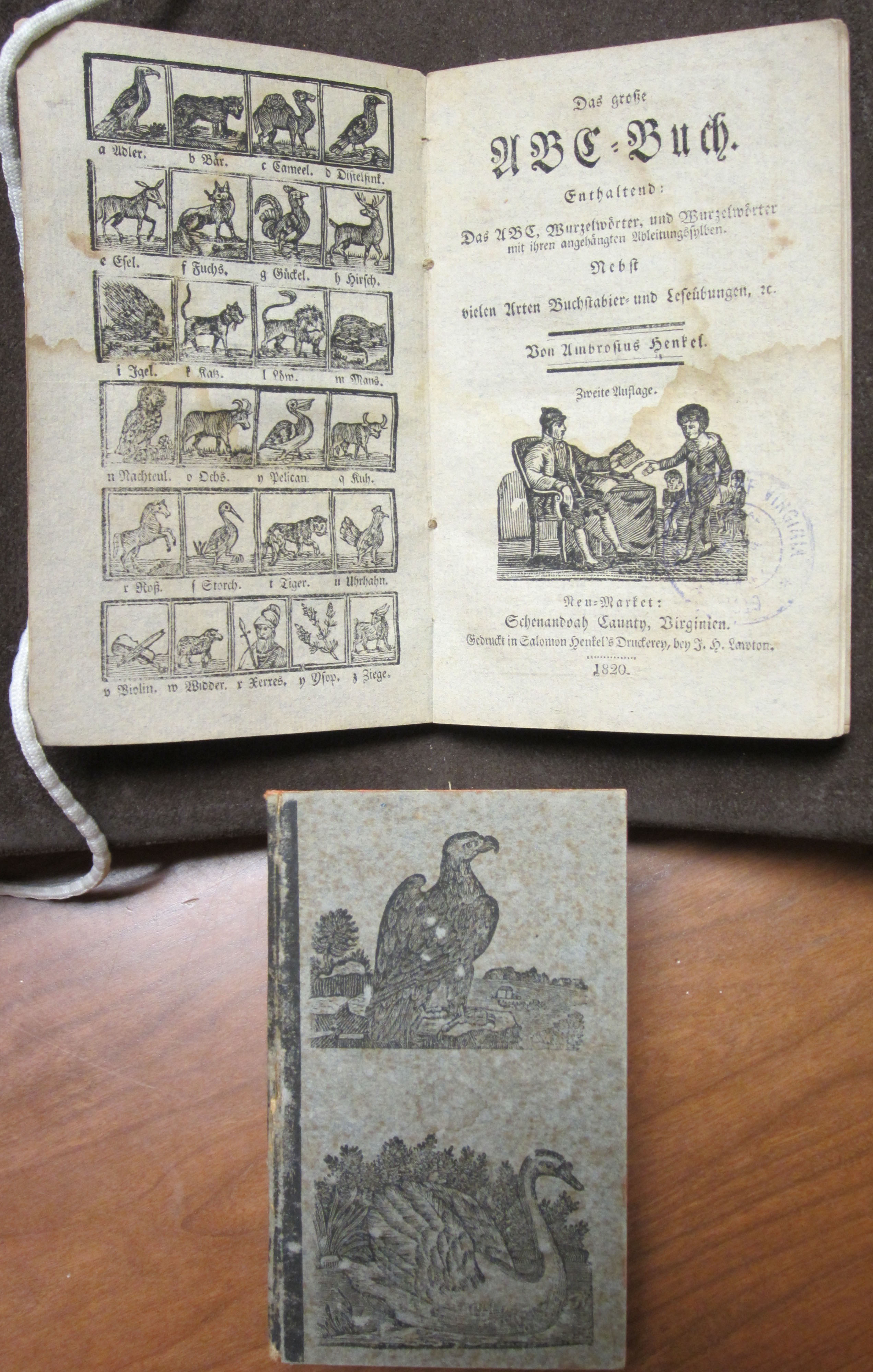

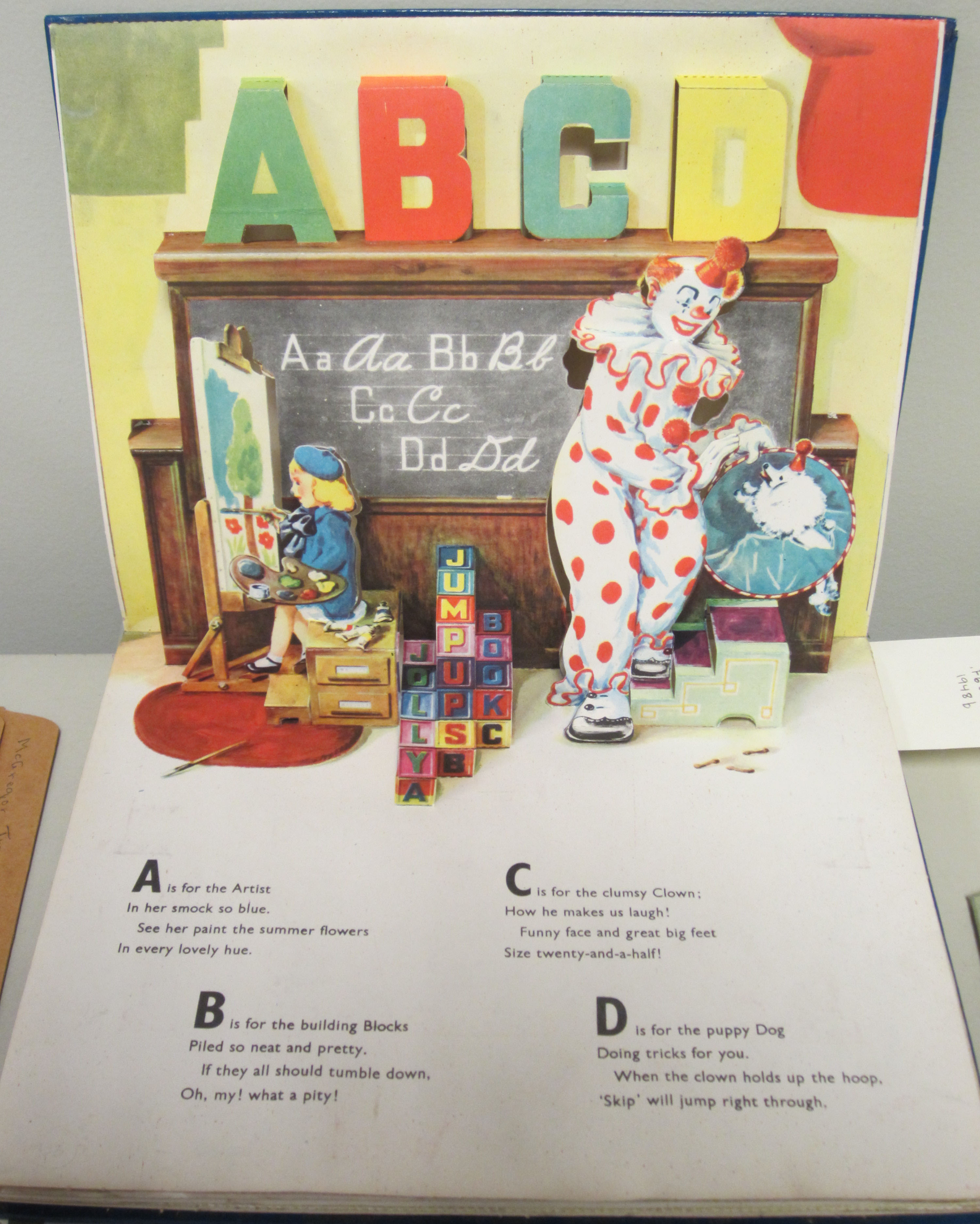

McGregor Grant Project work began on January 13, 2014, and ten days later the first scanned book was posted online: Amerigo Vespucci’s account of his third exploratory voyage along the Brazilian coast, published in Strasbourg in 1505. Since then the skilled student and professional staff of the U.Va. Library’s Digital Production Group have digitized a total of 136,067 pages from 547 rare McGregor Library works. Now researchers anywhere in the world may freely access these volumes by calling up their Virgo records, to which the images are linked. The books can be read using the Virgo image viewer or downloaded in PDF form. Concurrently project cataloger Yu Lee An substantially enhanced the Virgo records for 2,051 McGregor Library books—fully 10% of the entire collection.

The volumes selected for scanning and recataloging are not only the McGregor Library’s most significant works, but also those most heavily used for research and instruction. Mindful of our obligation to preserve these books for future generations, we can minimize wear and tear on these priceless works by offering more viewing options to infinitely more readers. Moreover, the digital images have been archived permanently so that the volumes should never need rescanning.