This week, we are pleased to feature a guest post from researcher Maria A. Windell, Assistant Professor of English at Ball State University. Dr. Windell visited Special Collections a few months ago to work on an article entitled “Military, Diplomatic, and Novel Imperial Imaginaries: Literary History and the Writings of David Dixon Porter,” about Civil War hero Admiral David Dixon Porter. It is drawn from a larger project on the Porter family and nineteenth-century literary history. While she was here, Maria found one particularly intriguing artifact that she generously agreed to share with us.

In March of 1855, Congress appropriated $30,000 for the purchase of…camels. The Army was hoping to find a more reliable and cost-effective way of navigating the American Southwest, as the broad swaths of territory gained just seven years before in the U.S.-Mexican War had proven difficult for horses to travel. Looking for a creative solution to these issues, the Army and Congress began to consider how camels might be adapted for transportation and perhaps even combat purposes in the United States.

A camel as illustrated in the “Report of the Secretary of War…respecting the Purchase of Camels for the Purposes of Military Transportation” (Washington: A.O.P.Nelson, 1857). (UC 350 . U5 1857. Bequest of Paul Mellon. Image by University of Virginia Library Digitization Services.)

Secretary of War Jefferson Davis (yes, future president of the Confederacy) tapped Major Henry Wayne of the Army to head an expedition to purchase camels for use in the U.S.; Wayne had long been interested in incorporating camels into the Army’s supply chain. Davis and Wayne then chose Lieutenant David Dixon Porter of the Navy to captain the Supply, the ship that would sail the camels from the Middle East to Indianola, Texas. Porter’s brother-in-law, Gwinn Harris Heap, who had lived in Tunis for many years, accompanied the expedition as, among other things, its resident illustrator.

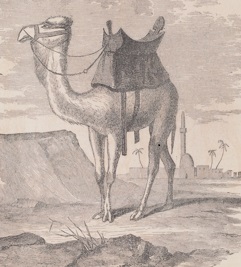

The expedition set out in 1855, and returned to Texas with thirty-four camels (including two calves born at sea) eleven months later. While the expedition was thus successful, the camel experiment ultimately failed. While the camels adapted quite nicely to the southwestern climate and landscape, Americans—and their horses—were unable to accept the aroma and mannerisms of their new four-legged companions. More importantly, the Civil War arrived, drawing interest and funding from the experiment. Some of the camels were sold to circuses and zoos, some were sold to private individuals, and some escaped into the desert (Texans reported encountering feral camels even into the twentieth century).

Camels being loaded for transport, as illustrated in the report. (Image by University of Virginia Digitization Services)

While the expedition failed to yield a permanent “Camel Corps,” it did yield a fairly comprehensive governmental report. At the request of Congress, Davis published a volume on the experiment with the rather utilitarian title Report of the Secretary of War, Communicating, In Compliance with a Resolution of the Senate of February 2, 1857, Information Respecting the Purchase of Camels for the Purposes of Military Transportation. The report is mostly a series of dispatches from Major Wayne and Lieutenant Porter; a number of Heap’s illustrations are included, as are the entries into the Supply’s log for the trip back to the U.S. Wayne also submitted lengthy excerpts and translations from various tomes on the camel, and Davis incorporated these into the report as well. There are certainly some entertaining events and illustrations to be found in the approximately 240-page report, but much of the volume is filled with mundane dispatches and camel arcana.

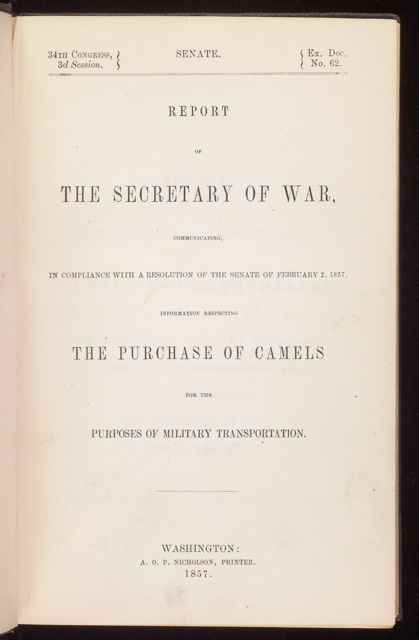

Title page of the report. (UC 350 .U5 1857. Bequest of Paul Mellon. Image by University of Virginia Library Digitization Services.)

In some ways, the publication of this 1857 report might be seen as the end of the expedition (the experiment took several years to peter out). Yet the report is in some ways also the beginning of the story of the camel event—it demonstrates how the experiment became a narrative of national interest before becoming a forgotten element of the national past. And the particular copy of the report held in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia demonstrates this in a particularly vivid way: it bears an inscription showing the volume to have been gifted. While it was quite common for novels, poetry, and story collections to be gifted during the nineteenth century, the gifting of a War Department report published for congressional use was certainly not the norm.

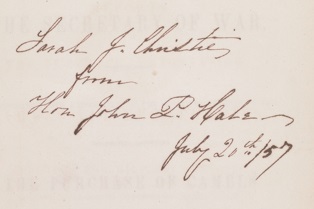

The inscription in UVa’s copy of the report. (Image by University of Virginia Library Digitization Services.)

The inscription in UVa’s copy of Davis’s Report reveals that such was the unusual fate of this particular volume. At the time of the report’s publication, John P. Hale was a United States Senator from New Hampshire. Sarah J. Christie was the daughter of an attorney Hale had practiced law with in Dover, NH, years before. At the time he gifted the volume to Christie in 1857, Hale had likely long been married to Lucy Lambert (the Hales’ daughter, Lucy Lambert Hale, was engaged to John Wilkes Booth at the time of Lincoln’s assassination in 1865). While the inscription does not then necessarily imply a romantic gift, it does reveal that Hale believed Christie would be intrigued by the report.

Hale’s gifting of the report on the camel expedition to Christie demonstrates the appeal of the expedition for Americans further removed from political and military duties. As the volume is clean of Christie’s—or any other—marginalia, there is no way to judge of her reaction to the report. Nevertheless, Hale clearly assumed it had enough interesting content to offset its overall tedium: accounts of Tuscany, Tunis, and the Crimea; of slight diplomatic rows with Turkey and Egypt over substandard gifted camels (the insult!); and of the birthing of calves while at sea. The possibility of baby camels certainly captured the imagination of the staff at Harper’s Weekly, which (prematurely) declared the camel experiment a success before noting, “The Secretary of War, Mr. Jefferson Davis, has not yet had the pleasure of presenting to the people a native camel.[. . .] It is, perhaps, indiscreet to attempt to be precise in promising the advent of little humpbacked strangers; but we can assure the public that the hopes of the Department are very high and confident.”

While the camel expedition and experiment may have captivated nineteenth-century Americans, it faded into a largely forgotten event—overshadowed in national memory, as it was at the time, by the enormity of the Civil War. The volume held in Special Collections, however, attests not only to the strange and interesting event’s occurrence, but also to the remarkable interest it generated—even inspiring the gifting of a governmental report initially published for congressional use.