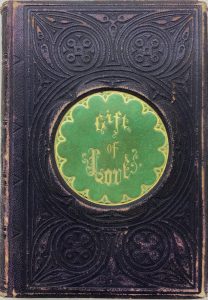

A book with arsenical emerald green inlay. Rufus W. Griswold, Gift of Love. New York: Leavitt and Allen, 1850. (PN6110.E5 G7 1850)

This post was written by Charlie Webb, a fourth-year student majoring in art history and working with our conservator Sue Donovan through the University Museums Internship. Charlie enjoys historical costuming and craft and can be found practicing viola as a member of the Charlottesville Symphony, fencing with the Virginia Fencing Club, or attempting to climb the hills of Charlottesville on an ancient mountain bike.

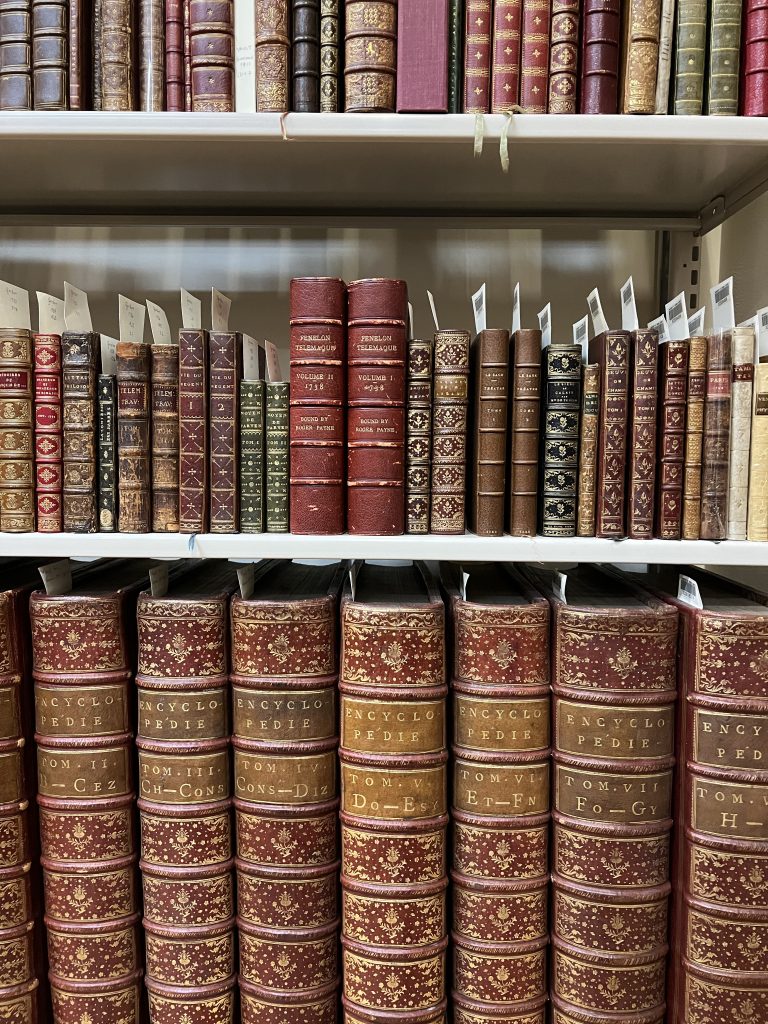

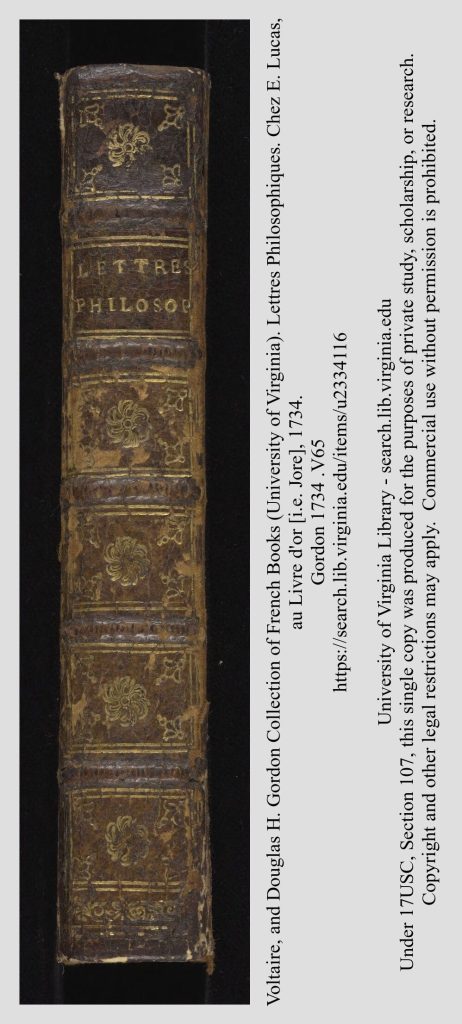

In mid-19th century England, France, and the U.S., a new trend arose across fields of textile and paper artisanship. Chemists discovered that, by including arsenic and copper in their dyes, they could achieve a range of incredibly vibrant green pigments. From approximately 1830 to 1870, arsenical pigments were used in many decorative effects, from bright green cloth binding to powdery green inlays and inks for colored engravings. Today, the Winterthur Library in Delaware has developed the Poison Book Project, which includes a list of books that have been tested to include the specific combination of arsenic and copper that produces a poisonous-looking color—arsenical “emerald green” bookcloth (Marcoon, 2021). The interest in arsenical books lies in concerns of safety, as pigments containing arsenic can flake off and be unintentionally ingested by those handling the books. With frequent exposure, or in large amounts, these arsenical pigments can cause skin and lung irritation, skin lesions, and even cancer of the skin and lungs (Arsenic, 2024).

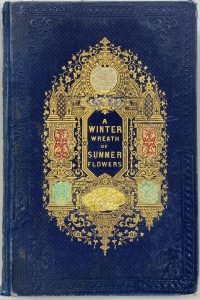

This ornate book cover features floral and architectural designs with arsenical green inlay. Samuel Griswold Goodrich, A Winter Wreath of Summer Flowers. New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1855. (PZ9.G625 W55 1855)

The Poison Book Project works to identify books that contain this chemical combination in order to safely house them for future research and, eventually, add them into the larger list of known arsenical books. In Special Collections conservation, our process for analyzing potentially arsenical books broadly follows the structure outlined above. After cross-referencing the arsenical book database provided by Winterthur with the UVA Library’s collections, we searched the library stacks for those books that had previously been tested by Winterthur—most of which were found in the Special Collections library. In analyzing “emerald green” bookcloth and decoration, it was necessary for us to visually identify the book as potentially containing arsenic before continuing with elemental analysis. Because of the variations in the 19th-century publishing industry, books from the same edition could be bound very differently, so many of the volumes on the Poison Book Project list that were in UVA’s collections were not bound in green cloth at all.

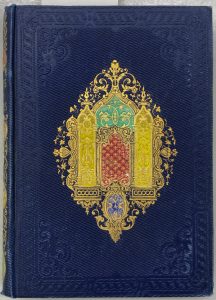

This book, bound by the same publisher as that of the previous book, features similar decoration. Samuel Griswold Goodrich, The Wanderers by Sea and Land: With Other Tales. New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1855. (PZ9.G625 W27 1855)

Once a book was visually identified by its vibrant green color, we tested it using an XRF (X-ray fluorescence) spectrometer, a tool that identifies the elements composing a material by analyzing the unique peaks each element gives off when excited by X-rays. For those books that contained any amount of arsenic, especially in combination with copper and iron, we enclosed them in inert plastic bags along with a Poison Book Project slip explaining the hazards of handling the book and replaced them on the shelf. Throughout this entire process, we took great care not to touch potentially arsenical objects with bare hands and designated one person to handle the books while the other wrote slips and recorded notes, in order to minimize potential contamination. Additionally, while we focused our analysis on those books already confirmed by the Winterthur study, we took note of those areas of the stacks that housed many books with the characteristic arsenical green color for later analysis.

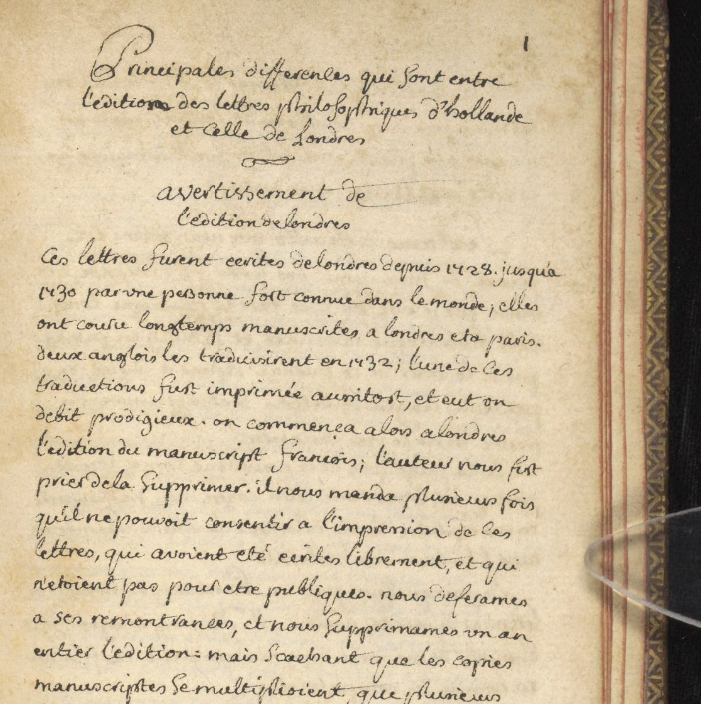

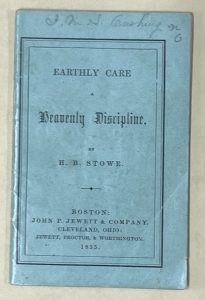

Despite its unassuming minty color and size, the paper covers of this book contained over 24 ppm (parts per million) of arsenic—the highest concentration of arsenic we encountered during the project! Harriet Beecher Stowe, Earthly Care: A Heavenly Discipline. Boston: Boston: John P. Jewett and Co.; Cleveland, Ohio: Jewett, Proctor and Worthington, 1854. (PS2954.E3 1854)

Eventually, the goal of the Poison Book Project is to safely house arsenical books so that they can be studied without the dangers that come with handling arsenic. Fortunately, such limited handling of these books does not restrict the information within. Most of the arsenical books that we have identified have duplicates elsewhere in UVA’s collections, and the arsenical copies can still be handled in the Special Collections reading room with the necessary protective equipment. The information that we have collected about the arsenical books at UVA will be shared with Winterthur to be added to their compiled list of “emerald green” arsenical books. And, as we begin to analyze previously untested books, we hope to be able to add new information about these books to the Poison Book Project’s database.

Citations

Arsenic. (n.d.). World Health Organization. Retrieved December 16, 2024, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/arsenic

IDing Arsenic Bookbindings. (n.d.). Poison Book Project. https://sites.udel.edu/poisonbookproject/arsenic-bookbindings/

Marcoon, A. (2021, December 29). Uncovering Undercover Toxins. Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library. https://www.winterthur.org/uncovering-undercover-toxins/