This year marks the 150th anniversary of the first publication of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Special Collections holds a collection of more than 1500 items related to this and Charles Dodgson’s other works, such as Through The Looking Glass and various works on logic and mathematics. The portion of the collection relating to Alice is the largest, and includes hundreds of editions as well as parodies, interpretations, and reimaginings of Alice’s adventures from all periods and in many different languages. This collection was built by U.Va. Professor of Philosophy Peter Heath, who taught at the university from 1962 to 1995. His own book, The Philosopher’s Alice (1974), juxtaposes the novel’s text with Heath’s own philosophical commentary.

In honor of Professor Heath’s collection, undergraduate Wolfe Docent Susan Swicegood curated the mini-exhibition “Happy 150th Birthday, Alice!” Faced with the daunting prospect of selecting just a handful of items from the remarkable Heath collection, Susan decided to focus on how illustrators have envisioned the figure of Alice herself over the course of the book’s publishing history. She did a beautiful job, and has filled three exhibition cases with items to stimulate memories and artistic inspiration for all generations of Alice readers. Here are just a few examples to tempt you:

This detail comes from a pop-up edition advertised as a “come to life panorama.” With her rosy cheeks and curly hair, this Alice looks more like a cherub than a curious Victorian child. Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, illustrated by A. L. Bowley. (London: Raphael Tuck, [1920s]). (PR 4611 .A7 1920b). Peter Heath Lewis Carroll Collection. Gift of Diana Salcedo and Philip Heath.

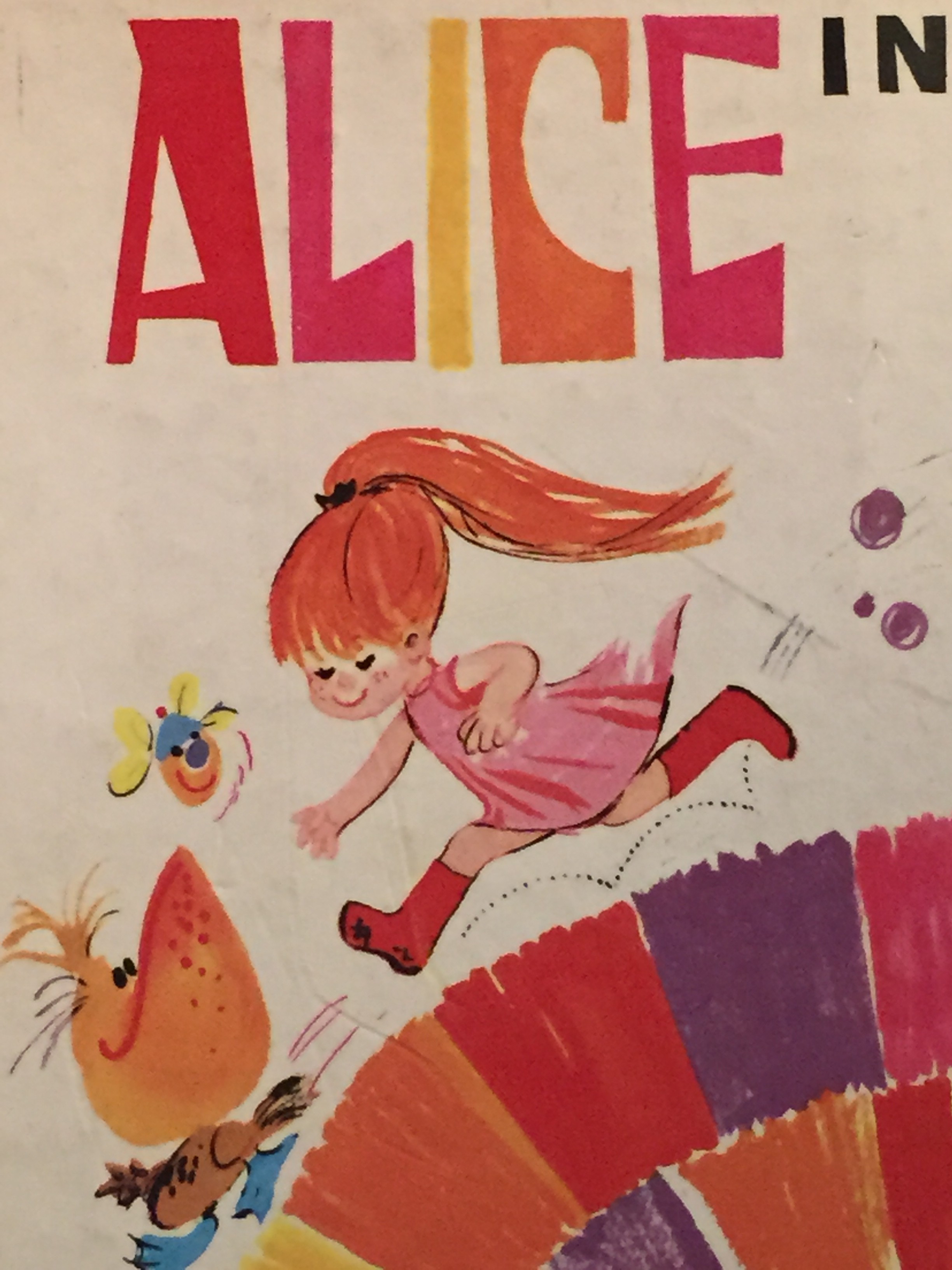

- Alice parodies use the book’s playful structure as an avenue for political or social commentary. This space-age Alice no longer travels down a rabbit hole, but to a new planet. Renzo Rossott, Alice in 2000, illustrated by Grazia Nidasio. (London : Ward Lock Limited, [1970]) (PR4611 .A72 R68 1970). Peter Heath Lewis Carroll Collection.Gift of Diana Salcedo and Philip Heath.

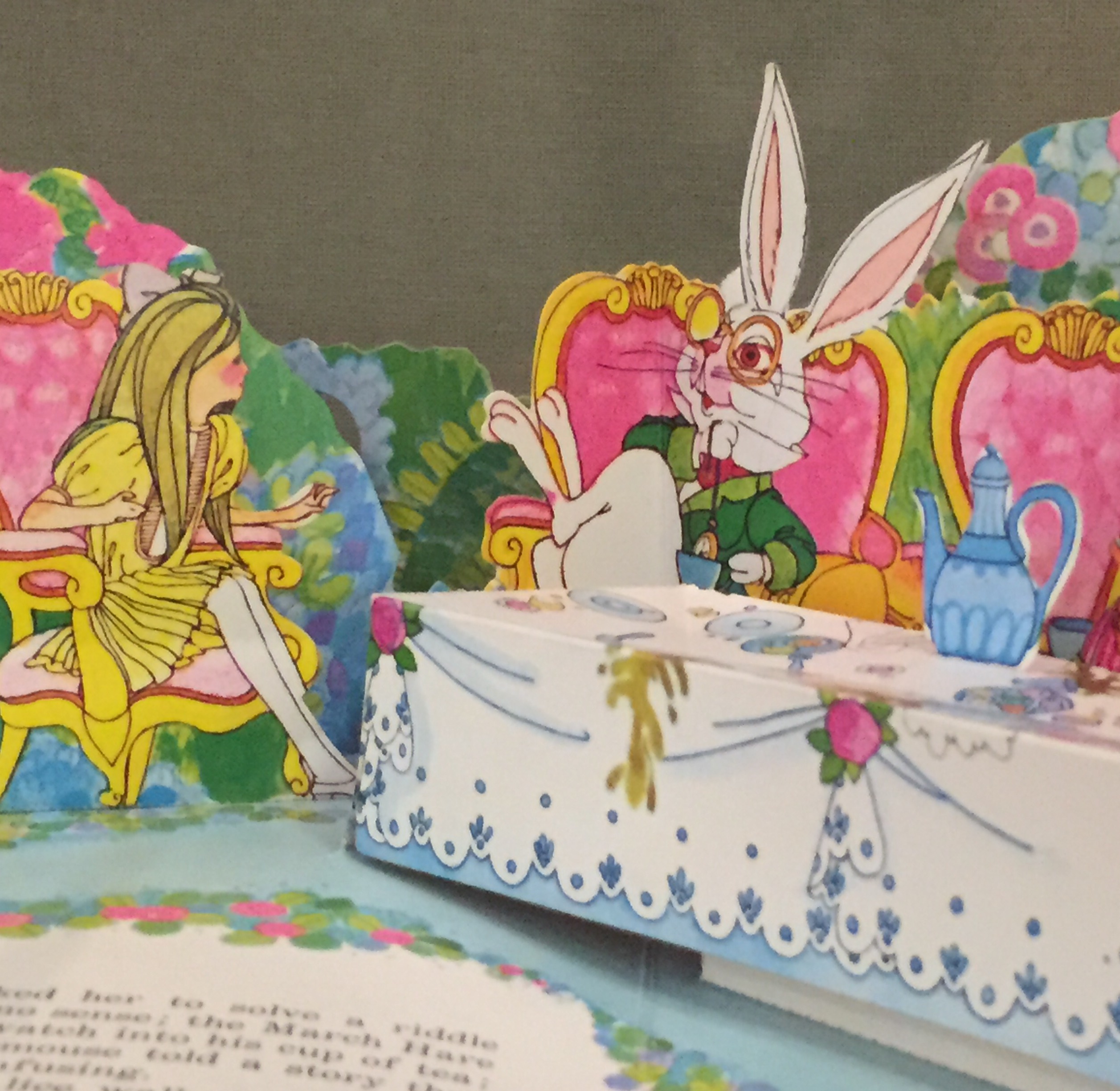

Alice got a big makeover in the 1970s, as modern printing techniques gave illustrators brighter and more dynamic colors that embody childish imagination, and finally giving Wonderland its psychedelic flair. This beautiful pop-up book displays a fabulous, hippie Alice at the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party. Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland Retold by Albert G Miller, designed by Paul Taylor, illustrated by Dave Chambers, Gwen Gordon and John Spencer. (New York: Random house [1968]) (PR4611 .A72 M53 1968). Peter Heath Lewis Carroll Collection. Gift of Diana Salcedo and Philip Heath.

The exhibition is broken into three sections: “The Origins of Alice,” which looks at how Alice’s visual identity first emerged, “Alice in the Golden Age of Illustration,” focusing on the lavish aesthetic of the early twentieth century, and “An Alice for Every Generation,” looking at Alices from the 1960s through our own time, with examples ranging from the iconic Disney animation aesthetic to the edgy pen and ink imaginings of Ralph Steadman.

We encourage you to stop by and visit the exhibition, which is on view in the First Floor Gallery through September 18. It’s a visual feast–or should we say, tea party?

![Engraved reproduction of the famous Dove Mosaic discovered by Giuseppe Alessandro Furietti at Hadrian's Villa and now in Rome's Capitoline Museum. Furietti believed it to be the actual mosaic created by Sosus for the royal palace at Pergamon, as described by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History. Giuseppe Alessandro Furietti, De musivis (Rome, 1752), plate [1]. (NA3750 .F8 1752)](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/X1.jpg)