Front cover of Cook’s Fremont: a poem (Salem, Mass., 1856) bound with The Eucleia (Salem, Mass., ca. 1865) (PS1378 .C7 1865; Robert & Virginia Tunstall Trust Fund)

Special Collections is world renowned for its printed and manuscript holdings of American literature, amassed through purchase, gift, and the happy receipt of several substantial collections, most notably the Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature. Deposited at the University of Virginia Library in 1960 and gradually given to the Library over the next three decades, the 250,000-item collection comprehensively surveys American literature in all genres from ca. 1775 to 1950. On its arrival the Barrett Library was rather awkwardly arranged in terms of “major” and “minor” authors—distinctions which of course lose meaning as literary reputations wax and wane and as scholarly interests shift.

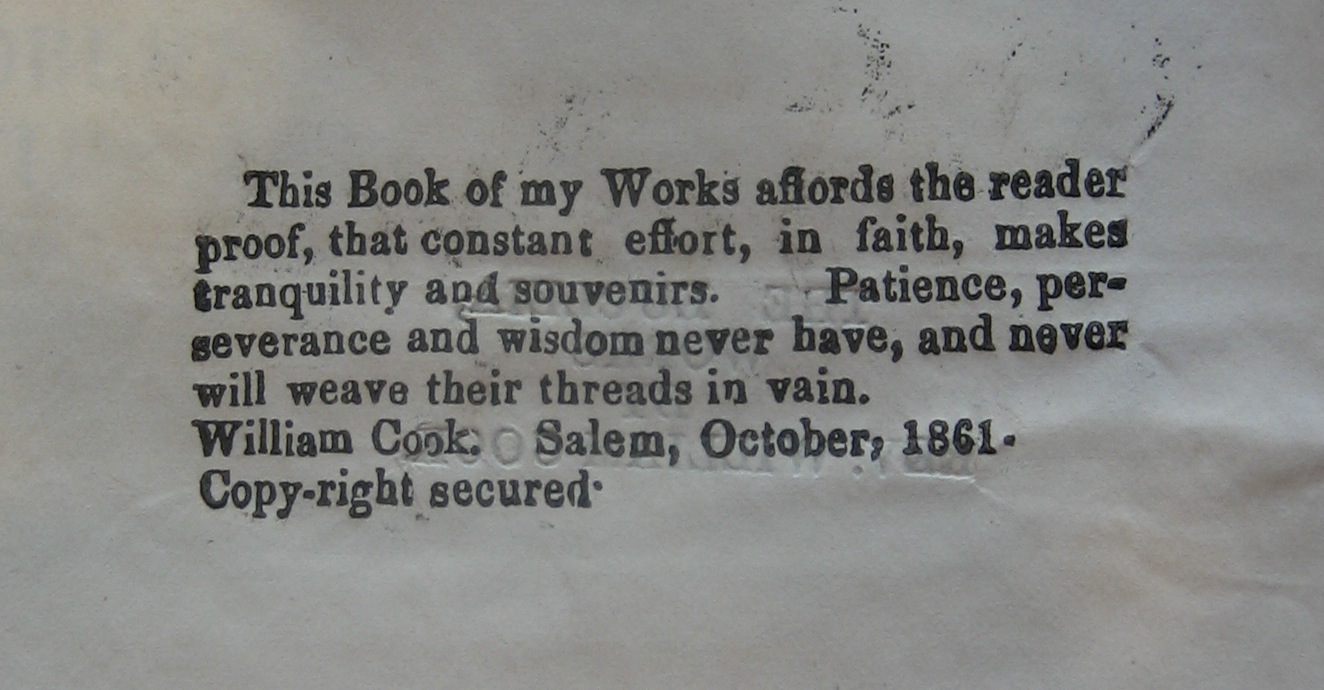

Title page verso to William Cook, The Eucleia: works (Salem, Mass., ca. 1865) (PS1378 .C7 1865; Robert & Virginia Tunstall Trust Fund)

This week’s post highlights one of these “minor” authors—William “Billy” Cook—whose work deserves wider recognition. The son of a ship captain and a lifelong resident of Salem, Mass., Cook (1807-1876) studied at Yale before his ambitions were checked by physical and mental illness. Back in Salem he conducted a private school for some years, where his students studied Latin, Greek, and mathematics (at which Cook excelled). He also studied for the ministry and conducted religious services at his home, though Cook never advanced beyond the rank of deacon. Beloved for his eccentricities and known locally as “Reverend,” Cook was for decades a fixture of Salem life.

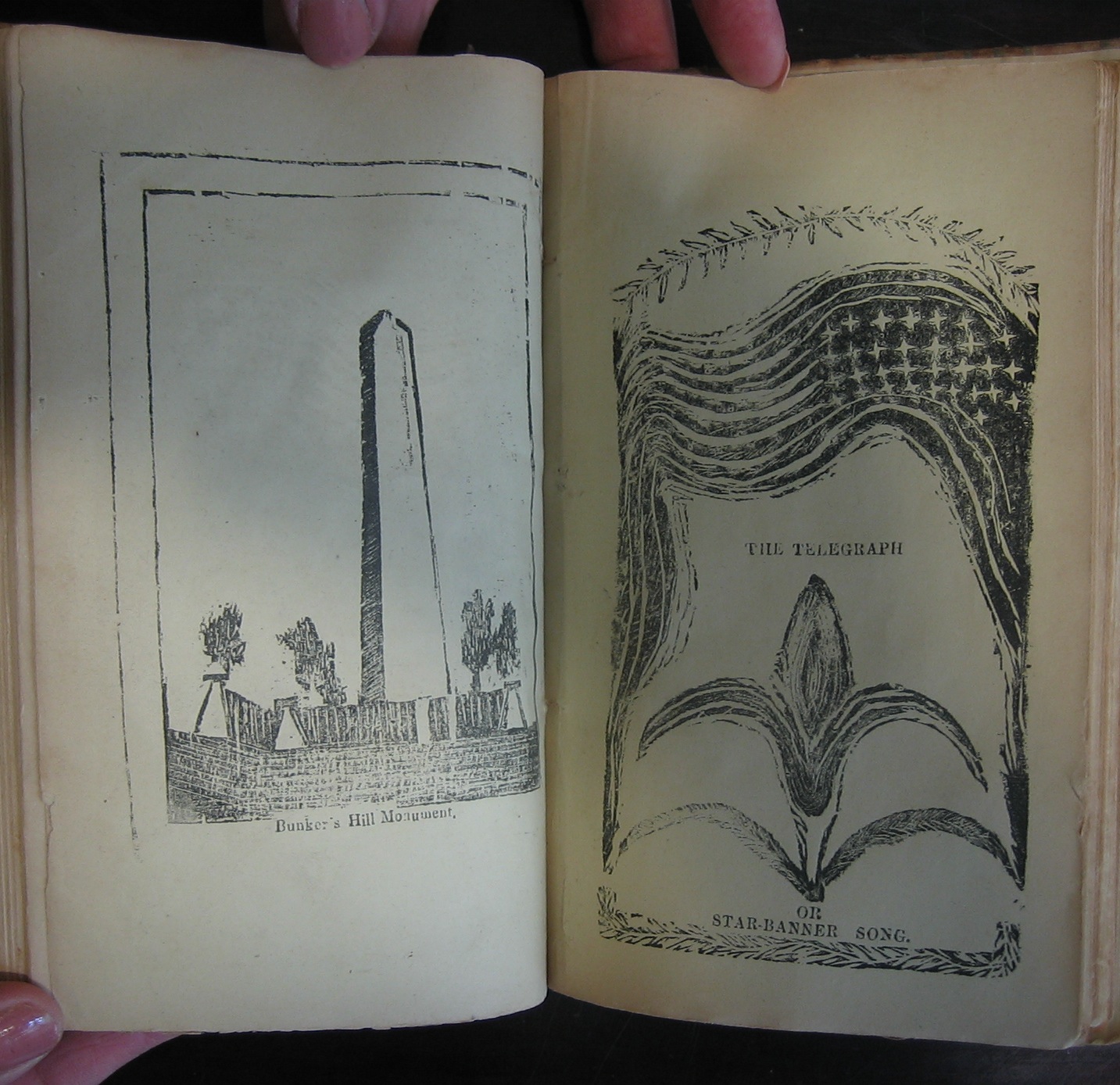

Back cover of Cook’s The Ploughboy, part third (Salem, Mass., 1855) and front cover of his The Telegraph, or Star-banner song (Salem, Mass., 1856); both bound with The Eucleia (Salem, Mass., ca. 1865) (PS1378 .C7 1865; Robert & Virginia Tunstall Trust Fund)

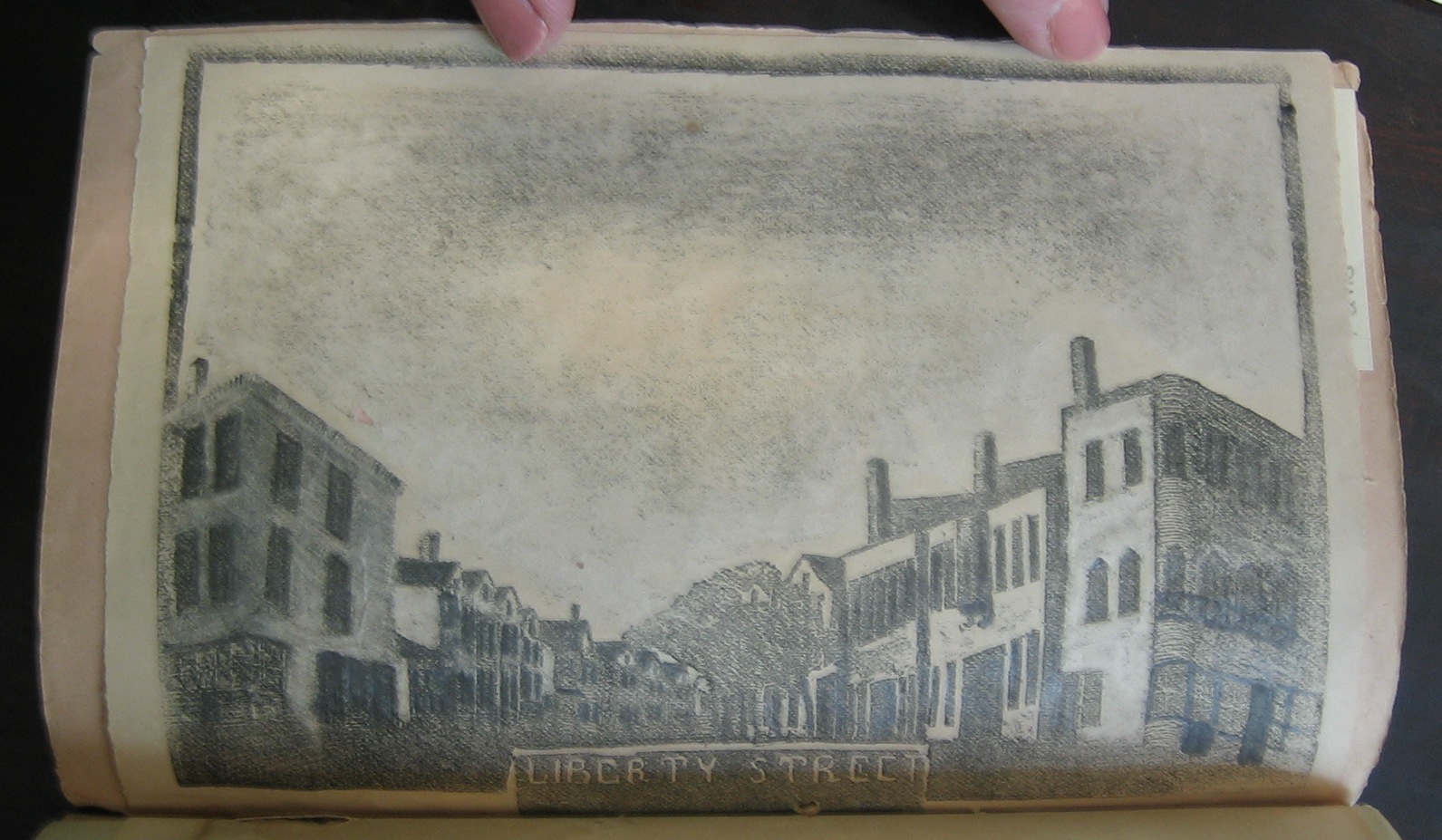

Finding himself jointly summoned in the early 1850s by the Muses of Poetry and Art, Cook began composing verse in which Salem and its residents, contemporary political events and figures, and various philosophical themes loomed large. Unable to afford the services of a commercial printer, Cook salvaged some worn type and a small cast-off jobbing press from a local newspaper office. With this equipment Cook could print only a page or two at a time, but time was a commodity he had in abundance. Over the next two decades Cook issued nearly 50 broadsides and poetry chapbooks, the latter hand-stitched by Cook in printed wrappers or bound in decorated cloth covers. Many were illustrated with Cook’s charming woodcut illustrations, which were typically heightened with pencil (mostly to correct uneven inking) and sometimes in colors. Because Cook often assembled and hand-bound his chapbooks in customized collections, his works exist in many variants.

Many of Cook’s woodcut illustrations (this one heightened with pencil) are contemporary depictions of Salem street scenes, such as this view of Liberty Street. William Cook, The Columbia (Salem, Mass., 1863) (Barrett PS586 .Z93 C673 C6 1863)

Strictly speaking, one might classify Cook’s works as examples of “mendicant verse,” a not uncommon sub-genre of 19th-century American minor poetry. Cook supplemented his modest income by peddling these chapbooks on Salem’s streets and to the increasing number of visitors who sought out his singular company. Late in life Cook took up painting, establishing a gallery in his home on Charter Street which attracted a new generation of visitors and chapbook purchasers. Although it would be stretching a point considerably to compare him with, say, William Blake, Cook is undeniably a fascinating practitioner of “folk” or “outsider” art.

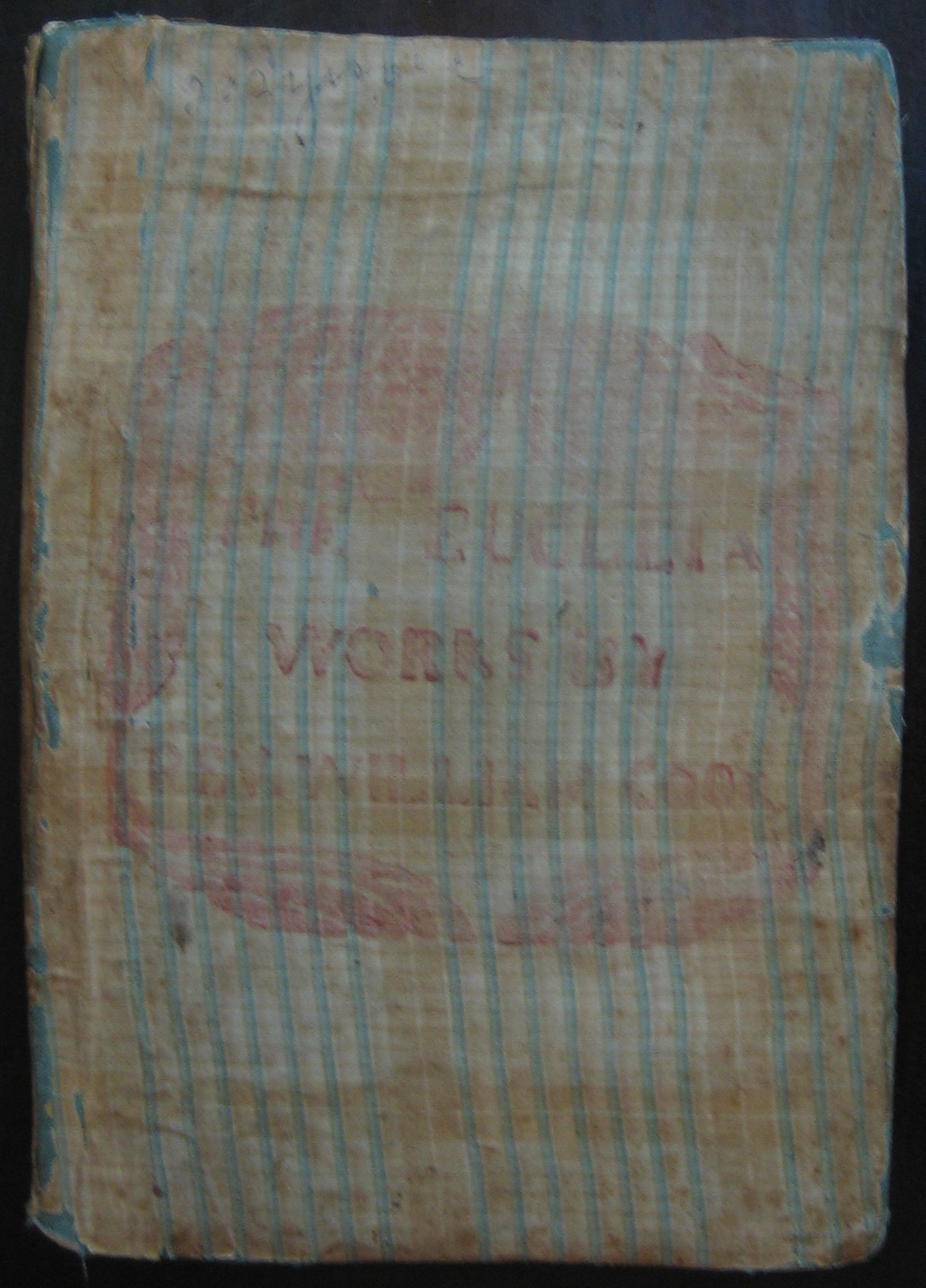

At one time it was not hard to find Cook’s ephemeral publications in New England, but today these are rarely encountered. Until recently the Clifton Waller Barrett Library could boast of holding only 13 Cook chapbooks. Now we have added ten more, increasing our holdings to approximately half of Cook’s recorded oeuvre. Fortuitously, all ten are gathered in one of Cook’s nonce collections, entitled The Eucleia with special added title page, hand bound by Cook in a remnant of striped cloth with woodcut title block stamped on the front cover. As far as we can tell, nothing has been written about Cook since 1924, when Lawrence W. Jenkins’s short article and checklist appeared in the Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society. Perhaps by having now gone “under Grounds,” Billy Cook will soon receive the attention he deserves.

Front cover of a William Cook nonce collection containing ten chapbooks, The Eucleia: works (Salem, Mass., this copy assembled ca. 1865). Cook bound this copy in a “publisher’s binding” covered in a striped cloth remnant with woodcut title stamped in red. (PS1378 .C7 1865; Robert & Virginia Tunstall Trust Fund)