This post by Ervin “EJ” Jordan Jr., Research Archivist & Associate Professor at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, concerns a recent acquisition, “Isabella, Jumain, Miriam and Rosa Letter,” March 7, 1865 (MSS 16853)

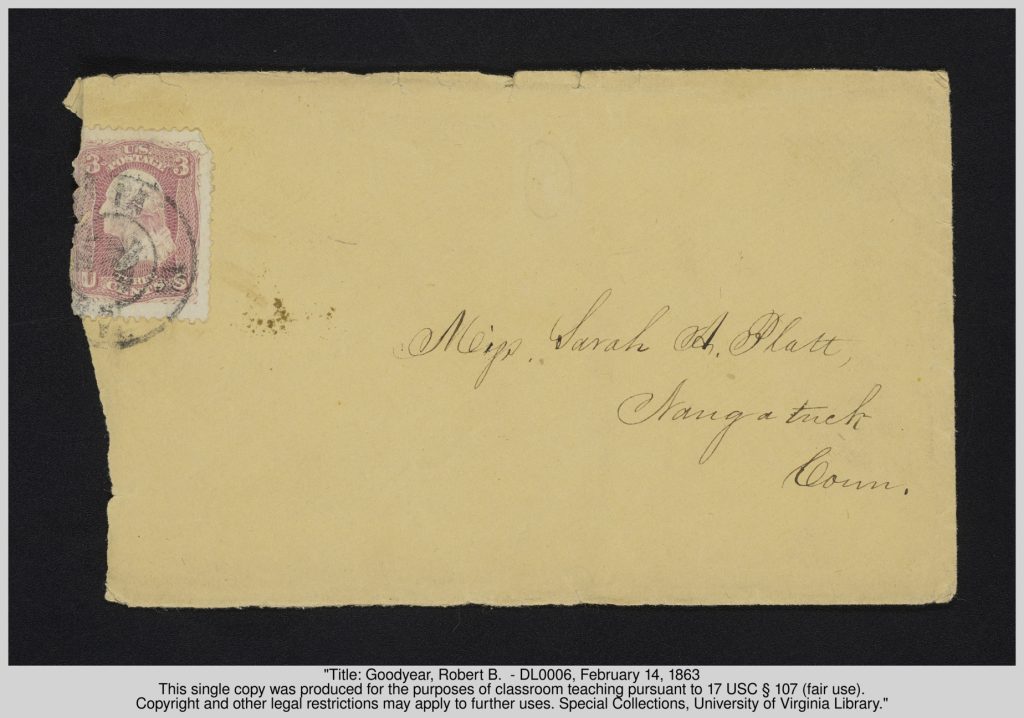

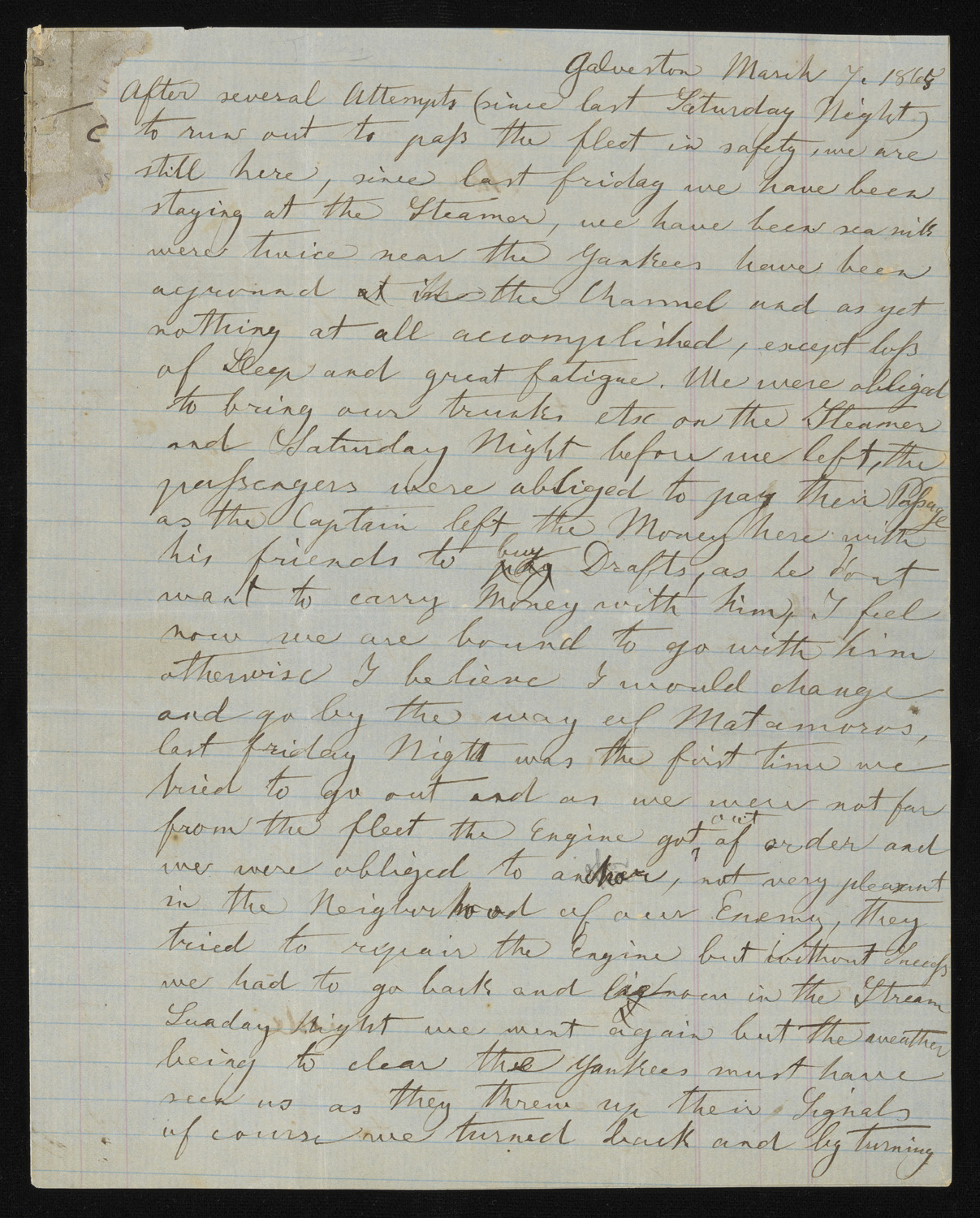

This document of historical rarity on a unique maritime aspect of the American Civil War was recently acquired by the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. It consists of March 7, 1865 letters of an anonymous family of four Confederate women Isabella and her daughters Jumain, Miriam, and Rosa (their surname unknown) to their husband/father in Havana, Cuba. Trapped by the Union Navy’s blockade of Galveston, Texas, their anxious departure attempts were a backdrop of Southern blockade-running activities (‘running the blockade’). Postal supply shortages and costs necessitated these letters’ single sheet of blue stationery; its 160-year survival implies receipt by the husband/father, interception by federal blockaders or never having been mailed. (Its cover envelope is missing). Extant letters by blockade runners’ civilian passengers are rare as mail confiscated by Union blockaders was usually destroyed.

Building a Blockade: Team Union Navy Blockaders

The Federal government imposed a naval blockade (April 1861-May 1865) of Southern seaports during the Civil War, patrolling 3,550 miles of coastline with a blockading fleet of 400 ships assigned to six geographically-based squadrons: Atlantic, North Atlantic, South Atlantic, Gulf, East Gulf and West Gulf. Captured blockade runners were taken to federal-held ports as war prizes, their cargo’s cash value shared among ships’ crews as prize money. Several seized vessels were commissioned for Union naval service. The blockade gave notice that foreign nations trading with the Confederate South risked confrontation with the United States. Although the smaller Confederate Navy (100 ships) never seriously challenged the Union Navy (700 ships) nor imposed its own blockade, Southern commerce raiders attacked Northern merchant vessels and whaling fleets in the Atlantic, Arctic and Pacific Oceans, decimating trade and increasing shipping insurance rates.

Breaking the Blockade: Team Confederate Blockade Runners

Southern blockade runners, privately or government-owned, were specially-built seagoing steamships constructed or purchased in Britian, Scotland and Ireland with large cargo holds and comfortable cabins. Known as “greyhounds of the sea” for their gray paint and swiftness, many bore colorful names like Let Her Rip, Rattlesnake, Banshee, and Vulture. One Confederate government-owned vessel, the Fingal (later the ironclad CSS Atlanta), returned from Europe in late 1861 with 10,000 rifles, 400 barrels of gunpowder, and a million bullets.

Blockade runners exported cotton for British textile industries, tobacco, sugar and rice to Europe in exchange for munitions, shoes, blankets, meat, coffee, medicines, and Bibles. They also carried civilian passengers and private and diplomatic mail to and from Europe and the South’s Atlantic and Gulf Coast ports (usually as night runs to avoid detection): Fernandina and St. Augustine, Florida; Beaufort and Wilmington, North Carolina; Charleston, South Carolina; Savannah, Georgia; Mobile, Alabama; New Orleans, Louisiana; Galveston and Brazos Island, Texas. Favored foreign ports included Liverpool (Great Britain), Bermuda, the Bahamas (Nassau), Halifax, (Nova Scotia, Canada), Tampico, Matamoras and Vera Cruz (Mexico), and Havana, Cuba. European nations were officially neutral but vessels owned or crewed by their citizens dominated blockade-running. After the war international arbitration (the Alabama Claims, 1869-1872) resulted in Britain’s compensating the United States $15.5 million for ‘damages’ caused by British-built Confederate ships.

Blockade-running was a business often financed by joint stock ventures euphemistically known as ‘exporting and importing companies’ whose investors reaped profits ten times their cargoes’ original value. Such voyages were inherently perilous–1,500 ships were run aground, captured or sunk, drowning crews and passengers. “King Cotton” exports slumped by 95 percent; the Confederate South’s cotton embargo strategy to pressure European intervention in the war failed, contributing to its ruined economy.

The golden age of blockade-running ended by the early spring of 1865 as the Union army and navy increasingly captured Confederate seaports; though blockaded, only Galveston remained under Southern control. Ironically, blockade runners’ successes may have helped strangle the blockaded Confederacy by increasingly trafficking extortionately-priced luxury goods like silks and champagne while Confederate armies suffered shortages of badly-needed military supplies.

The Letter(s): “We have had some adventures”

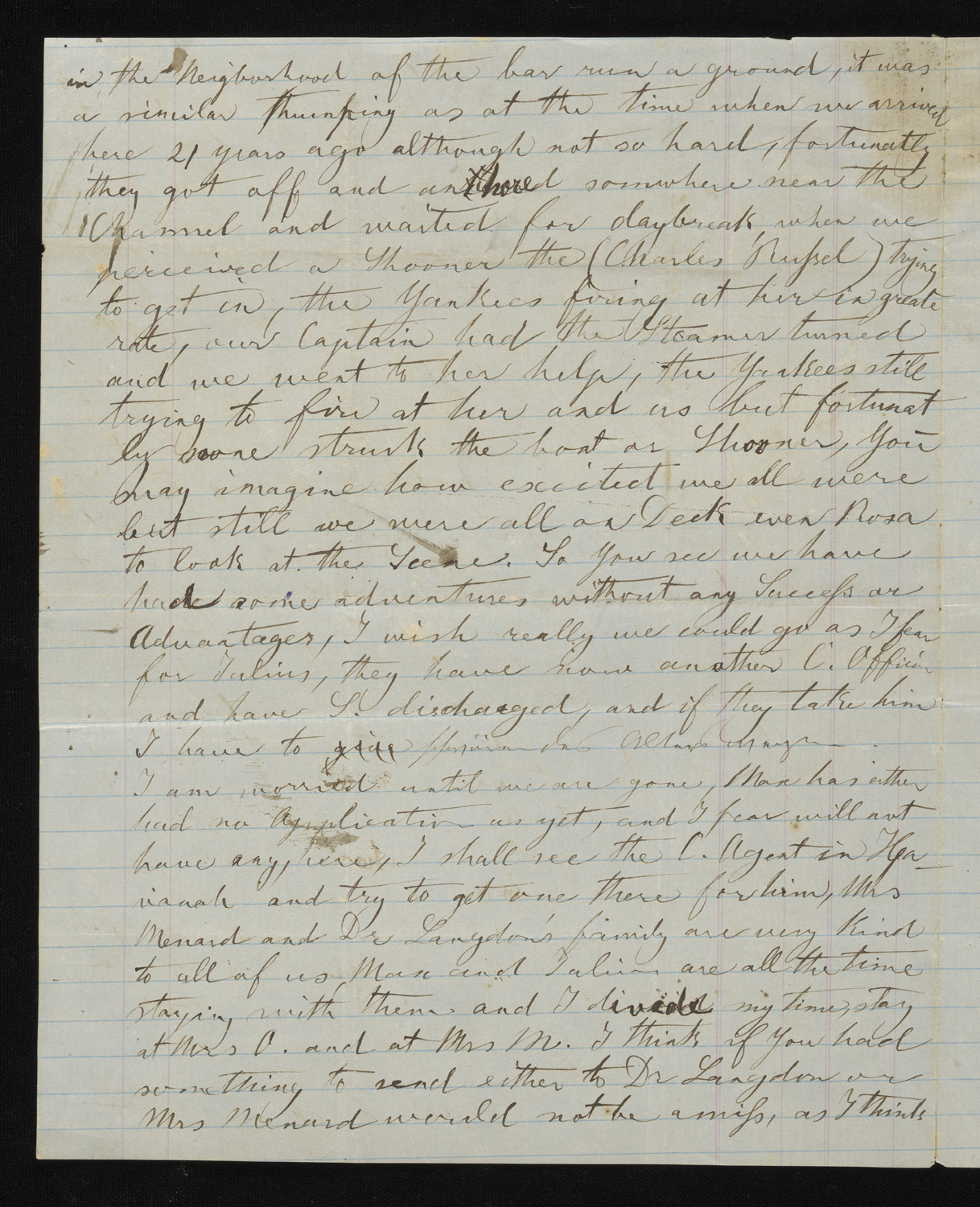

In the first of this anonymous family’s four March 7, 1865 Galveston letters, “Isabella” writes to her unidentified husband of her frustrated attempts to join him in Cuba via Matamoras, Mexico—a regular route for self-exiled Confederates. Several tries by an unnamed blockade runner [paddle steamer CSS Lark?] on which she and their three daughters booked passage, had been thwarted by Union ships [the West Gulf Blockading Squadron, 990 miles of the Gulf of Mexico coastline from St. Andrews Bay, Florida, to Texas-Mexico border] “since last Saturday night” (March 4). Their misfortunes (“We have had some adventures, without any Success or Advantages”) were compounded by seasickness, “loss of Sleep and great fatigue,” their ship’s running aground and frequent engine trouble, barely avoiding seizure. An incoming schooner, Charles Russel, was turned away because of “Yankees firing at her in great rate.” Isabella provides a clue of the family as Texans, remarking “when we arrived here 21 years ago” [1844] and concludes: “I must close now the Children want to add some[.] I wish you farewell again with the hope of Your Health and Happiness.”

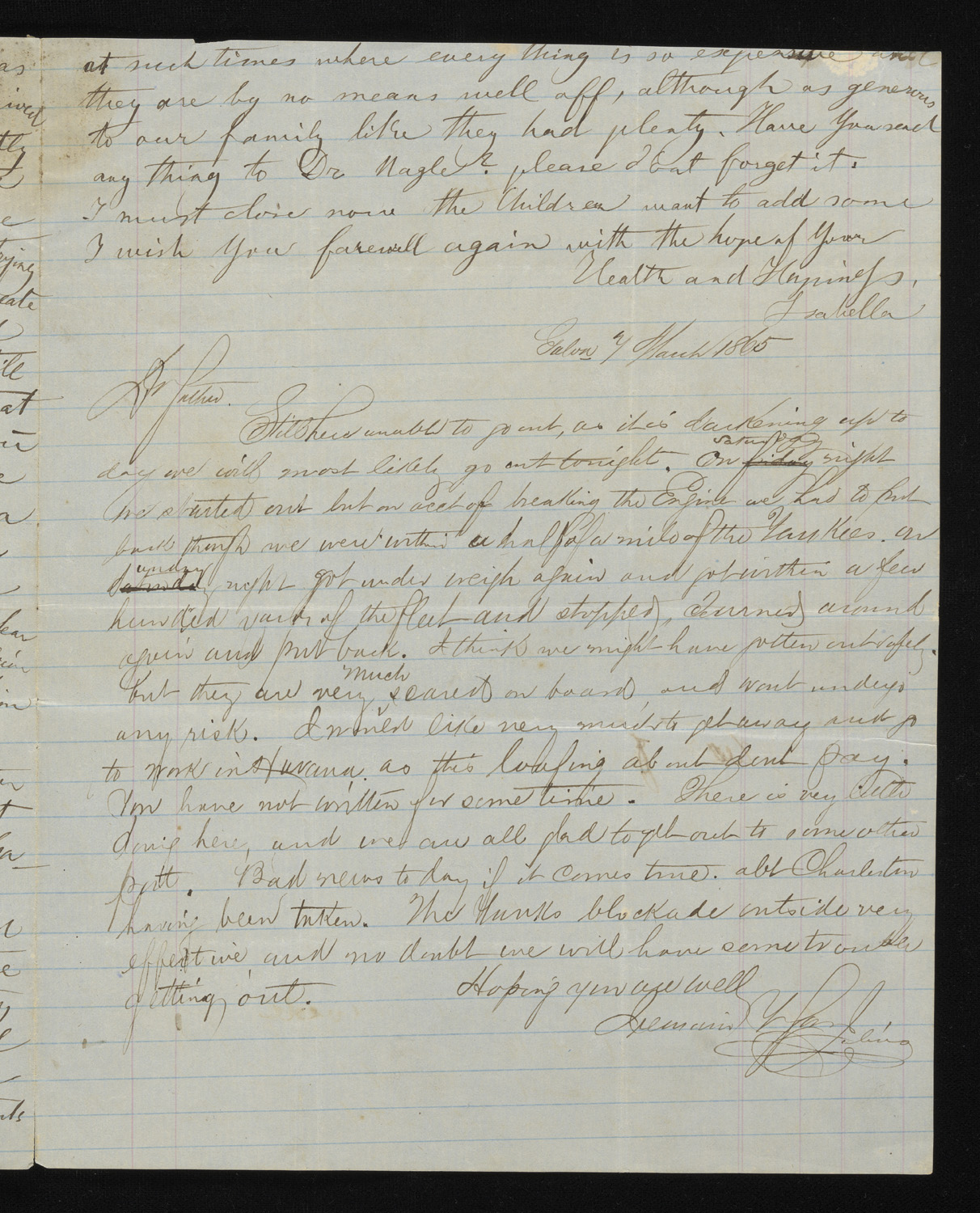

The second letter, “Jumain” [eldest daughter?] to “Dear father,” offers sentiments similar to her mother’s. She relates another sailing attempt Sunday night (March 5) that only traveled a few hundred yards, stopped by engine troubles a half mile from the Yankees, forcing a return to Galveston. Another attempt was planned for that night (March 7) but she concedes the “Yanks blockade outside very effective, and no doubt we will have some trouble getting out.” She hopes for gainful employment in Havana “as this loafing about don’t Pay” and concludes “Bad news today if it comes true about Charleston having been taken.” [Confederates evacuated this South Carolina city in February 1865; Union troops subsequently burned it.]

The third letter, “Miriam” [middle daughter?] to “Dear father,” complains: “We have not as yet departed for one reason or another, but if we do not get out tonight we will probably have to stay until next moon.” She says because “Mother” (Isabella) had already written about “our proceedings” it would only trouble him to repeat them.

The fourth and last letter, “Rosa” [youngest daughter?] to “my dear father” in childlike handwriting, is the briefest: “I bid You good bye again.” In a penciled postscript her mother Isabella reports interrupting Rosa’s initial use of ink because it was in short supply. (The first seven letters “my dear f” are in ink.) Isabella made her use a pencil “fearing she would [turn] the ink over” but Rosa apparently pouted at being denied an ink pen: “She does not like [using] the Pencil and therefore only bid you good Bye.”

![Fourth page of a handwritten letter, containing two notes: first, “Miriam” [middle daughter?] to “Dear father" dated March 7th, 1865; the second, from “Rosa” [youngest daughter?] to “my dear father.”](https://smallnotes.library.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/000059429_0004.jpg)

The Confederacy never lifted the Union blockade, and the war ended a month after the family’s last known breakout attempt; subsequent efforts, if any, are unknown. On May 24, 1865, the South’s last blockade runner, CSS Lark (built in England for the Confederate government), departed Galveston for Havana. Three weeks later, June 19, 1865, during its postwar Union military occupation, Galveston became the birthplace of Juneteenth.

Select Bibliography

Dead Confederates, A Civil War Era Blog,“Builder’s Drawing of Wren and Lark.”

Heidler, David and Heidler, Jeanne, eds. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000.

Mr. Edwin W. Hemphill, University of Virginia Library “Bibles from Britain for the Blockaded Confederacy,” 29 May 1949, MSS 3224, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections, University of Virginia Library.

Isabella, Jumain, Miriam and Rosa Letter, 1865, MSS 16853, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections, University of Virginia Library.

The New York Times, February 2, 1865: “Correspondence of the Associated Press/HAVANA, Saturday, Jan. 28.”

U.S. Naval War Records Office, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion Series 1, vol. 22. Washington: GPO, 1894-1922.

Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia: “CSS Lark”; “Danish West Indies”; “History of Galveston, Texas”; “List of ships built by Cammell Laird”; “Postage stamps and postal history of the Confederate States.”

Wilson, Paula. St. Croix Landmarks Society, 2007, https://www.stcroixlandmarks.org/history/transfer-day/