This week we are pleased to share a guest post by two graduate students in the English department, Neal D. Curtis and Samuel Lemley who are currently doing research for a grant-funded project on the early history of the UVA Library. Neal, a 3rd-year PhD student, specializes in bibliography and the eighteenth century. Sam, a 4th-year PhD candidate, is working on a dissertation on antiquarianism as a literary mode in early modern England. Their project on the Rotunda Library is funded by a William R. Kenan Grant, an International Center for Jefferson Studies (ICJS) fellowship, and a research grant from the Institute of the Humanities and Global Cultures (IHGC) at UVA.

As part of an ongoing project on the design, history, and layout of the University of Virginia’s first library, we spent two weeks in the late summer this year deciphering cryptic shelf-marks in books. A shelf- or press-mark is a letter, number, or other sign stamped inside or on a book that signals the book-press, case, or shelf to which the marked book belongs. Often overlooked, historical shelf-marks can bring to light the provenance of individual volumes and reveal the ways in which collections were shelved and accessed in the past—a big deal for bibliographers and book historians.

The approximately 3,100 books (8,000 volumes) originally shelved in the Rotunda are known, thanks to a 29-chapter catalogue printed in 1828. This catalogue makes reconstituting the University’s first library relatively easy, but its historical arrangement in the Rotunda remains obscure. This is due in part to the scant information provided by the catalogues that survive. The 1828 catalogue and its 1825 manuscript precursor list titles, authors, and dates, but don’t specify how the books were arranged on the Rotunda’s shelves. A later catalogue, begun in 1857, adds shelf numbers beside each title, but presumably the books were also marked to prevent mis-shelving and loss.

In search of these hypothetical marks, we began by examining the first fifty books listed in the 1828 published catalogue. All of these books are classed in Chapter One (“Ancient Languages”), and most are still held in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library—a result of the fact that this section of the Rotunda library was shelved on the main floor of the dome room rather than in the upper galleries, which burned along with the books they held in 1895. (But that’s a story for another time…)

Our search revealed three types of shelf-mark, each representing a phase in the history of the collection:

1.

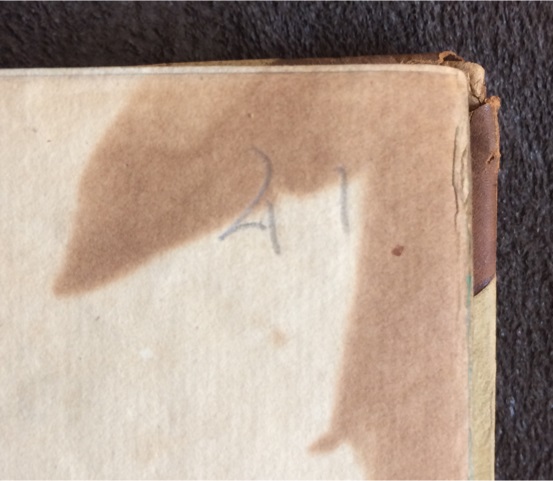

Type 1 shelf-mark: “41”, ca. 1825 (PA3458 .A2 1794, vol. 1)

The first and earliest type is rudimentary: a number penciled on the front flyleaf of each volume, indicating the chapter or subject heading to which the marked book belongs. This number evidently refers to chapter headings in 1825, and not those in 1828. We know this because the pencilled numbers fit a 42-part (or chapter) system employed in 1825 rather than the 29-part system devised in 1828. To clarify by way of example, a book that would be categorized in Chapter 1 (“Ancient Languages”) in 1828 is here labeled “41”, for Chapter 41 (“Philology”) in 1825. Confirming this prediction, the same book appears in the first chapter of 1828 and the 41st chapter of 1825.

2.

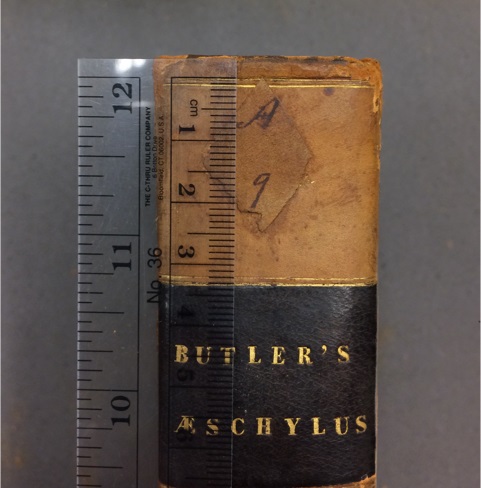

Type 2 shelf-mark: “A | 9”, ca. 1828 (PA 3825 .A2 1809a)

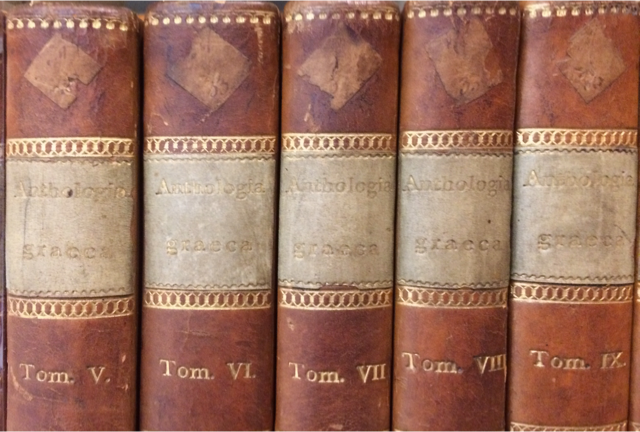

A set of books originally shelved in the Rotunda showing early shelf-marks on spines. (PA3458 .A2 1794, vols. 5-9)

The second type of shelf-mark is a small, diamond-shaped leather label pasted at the head of the spine of each volume. These labels list the shelf and position of each book in an alphanumeric shorthand. For example, the label pictured here specifies ‘A9’—that is, the book 9th in sequence on the shelf labelled ‘A’. Presumably the librarian would have known the case number based on the subject of the book; otherwise, the case number could have been found by consulting the catalogue and finding the book under the appropriate chapter heading. Evidently, this shelf-marking system endured: next to the same title in the 1857 catalogue appears ‘1A’, meaning that this book was shelved in the first case on the first shelf from ca. 1828 until ca. 1895, when the 1857 catalogue was replaced.

3.

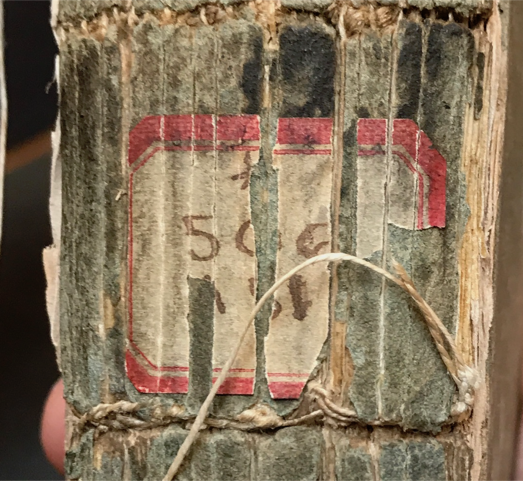

Type 3 Shelf-Mark, illegible. (Q11 .P6 n.s. v.2 1825)

Type 3 Shelf-Mark (trace): DDC call no., ca. 1896-1906 (PA3458 .A2 1794, vols. 1-2)

The third and latest type of pressmark is a red and white paper label pasted at the foot of the spine of each volume. Unfortunately, these survive only in fragments, and most have been removed entirely. However, the ink from some of these shelf-marks bled through, staining the leather underneath.These traces reveal that the call numbers on these labels belonged to Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC)—a system of library organization invented in 1876 and only implemented at the University of Virginia from ca. 1896 to 1906. It’s therefore safe to assume that these labels were added after the fire in 1895 when books were reclassified and re-shelved in the newly-renovated Rotunda. Presumably these labels were removed when the books were re-catalogued according to the Library of Congress Classification (LCC) system and transferred to Alderman in the 1930s.

The implications for this discovery are far reaching. We expect that additional research will establish the number and size of the shelves in the Rotunda, the distribution and organization of volumes in each case, and the aesthetic of the books arrayed in their original order beneath the Rotunda’s dome. Identifying these pressmarks will also enable researchers and special-collections staff to approximate the date a particular book was added to the collection. All of this, we hope, will help us paint a detailed portrait of the university’s first library in use.

Hello:

Very interesting research. I commend you on your undertaking.

But I strongly disagree with one of your conclusions. In the last sentence of your second paragraph you state: “A shelf-mark in a catalogue is useless without its corresponding mark on the book!” I disagree.

Assume you have a catalogue which list a book entitled: “The Anatomy of a Butterfly” and the catalogue states it is housed on shelf A-1. You do not need any mark on the book whatsoever to inform you where to place the Anatomy book. The book can contain no markings whatsoever and if the shelf identifier is listed in the catalogue one will know exactly where to place the book. (Maybe this is the responsibility of the librarian who may have the catalogue in hand and not the book user). (Or maybe it is the collector who wishes to have no marks in his books–thus they remain “pure”). Accordingly the catalogue is not “useless”. In fact if the book is unmarked, the catalogue is absolutely essential to inform you where to house the book.

Likewise if the Anatomy of a Butterfly is marked with “Shelf A-1”, you will know where to house even if the catalogue fails to identify the shelf or even if the catalogue fails to list the book. In summary you do not need the marking “Shelf A-1” on both the book and the catalogue.

However if you wish to identify the specific shelf, e.g. the physical location of the shelf within the library, the shelf will need to be marked or you will need a historical record to identify the physical location of shelf A-1.

Of course a catalogue listing the books grouped together on Shelf A-1 or pulling together and identifying all of the books with a marking of Shelf A-1 can be important, even if the marking is not on both the catalogue and book and even if the physical location of the shelf cannot be identified. It can tell us a great deal about the concepts of teaching and learning at the time of the markings. For example were art and law books shelved together at one time suggesting a similar discipline and approach and later separated or were they separate early and then grouped together later? (The art and law example is for illustrative purposes, not to imply any scholarship on that combination or lack thereof).

The physical attributes of a library are also a very interesting area of study. Comments about library architecture are outside the scope of my comments here, but very interesting work was recent completed on this subject. I cannot recall the title or authors, but maybe Mr. Goggle can find it. Likewise knowledge about the physical size of Thomas Jefferson’s libraries (extend of shelving and book cases and so forth) at both Poplar Forest and Monticello can aid the scholar in identify or confirming the extent of Mr. Jefferson’s libraries.

Again, thanks for the update on your work. Very interesting stuff.

Dennis

Dennis,

Right you are! Thanks for pointing out our error—I think we meant something along the lines of, “without corresponding marks on the books, the catalogue must be consulted every time the book is returned and reshelved.” “Useless” is far too strong a word here. I’ve asked the editor to change this. Stay tuned. Meantime, it seems you’ve thought about this. I’d be glad to correspond in future as we work out how books were arranged beneath the Rotunda’s dome. Thanks again.

Yep. I have thought about this stuff. I will try to find the architecture of libraries article I mentioned to you. Jefferson designed the Rotunda library shelves so standing in the middle you could not see the shelves. But I wonder if more was at work? I would enjoy keeping up with your work. Is there a way to keep in touch outside of this blog?

Dennis, you can reach me at svl6fy@virginia.edu — send a note so I have your contact information and we can correspond as our work progresses.

I’ve came across 5 sets of “POKER” Fauntleroy playing cards, Cincinnati, U.S. Playing Card Company, 1890-1912 (PS1214. L554 1886). They are in a hard cardboard holder, with step by step instructions, ‘how to play poker’. They also include the value of each card all the way to the Ultimate ‘ROYAL FLUSH’!

Could someone please help me to put the real value upon this antique collection?

We are unable to assist with evaluating your collection, but we can recommend where to go: the website “Your Old Books” has recommendations for how to find a reputable appraiser: http://rbms.info/yob/

This site is maintained by the Rare Book and Manuscript Section of the American Library Association. Good luck with your quest for information!