No, not that “Breaking Bad”! In fact, this writer confesses to having never seen the television series. Rather, this post concerns the practice of “breaking,” that is, disbinding a book or manuscript and dispersing the individual leaves, plates, or sections. The breaker believes that, at least in some instances, a book or manuscript is worth more broken up than intact. Breaking up a book or manuscript may increase its monetary value, enhance its pedagogical utility, result in irreparable harm to the cultural record, or paradoxically, all of the above. The question is a complex and controversial one, and opinions run the gamut from a willingness to break up anything for any expedient reason to the view expressed in the latest edition of John Carter’s ABC for Book Collectors: “Breaking up books, whether for filthy lucre or from higher motives, is wrong.”

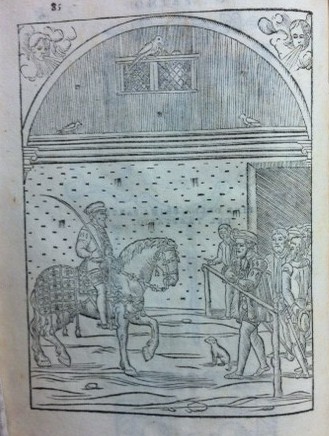

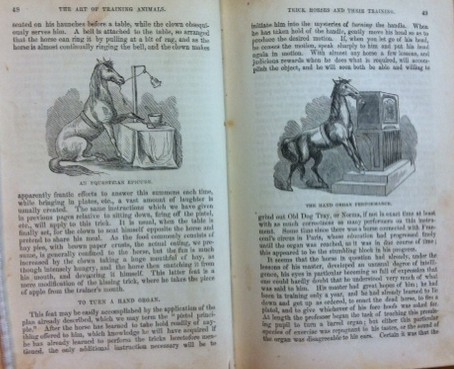

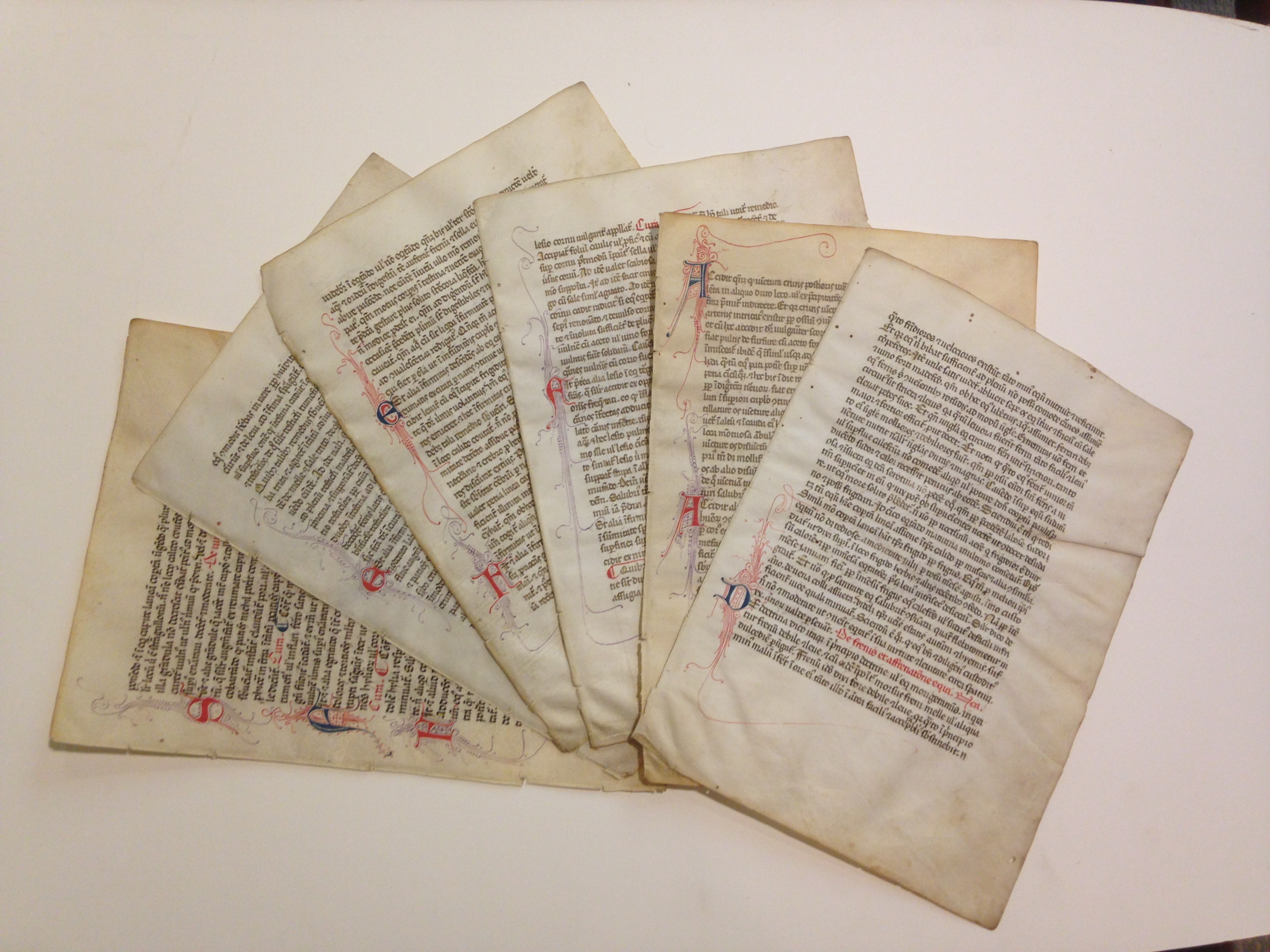

Disjecta membra: disbound, but not dispersed. Six recently acquired leaves from a mid-14th century manuscript of Giordano Ruffo’s De Medicina Equorum. (MSS 15703)

It has long been, and remains, a frequent practice among book and print dealers to break up color plate books—especially imperfect copies—and sell the plates individually, with the text often discarded. Although this practice has effectively placed John James Audubon’s spectacular double elephant folio Birds of America on the endangered editions list, how else could one hope to possess one of its hand-colored engravings? Some might cast a kinder eye on the bookseller Gabriel Wells, who in 1921 broke up a modestly imperfect copy of the Gutenberg Bible, selling the nearly six hundred leaves individually or in sections, tipped into a specially published “leaf book.” Thanks to Wells, dozens of educational institutions worldwide have been able to acquire Gutenberg leaves for instruction and exhibition (U.Va. owns two at present). And by breaking up dozens of imperfect copies, some significant and valuable, U.Va.’s Rare Book School has created an extraordinary teaching resource for the history of book illustration and typography that has been used by several thousand students to date.

Perhaps nowhere has the practice of breaking been more fraught than in the realm of medieval manuscripts. In the last century alone, hundreds of medieval codices (especially Books of Hours) have been broken up, with the illuminated and more highly decorated leaves sold as works of art, some of the remaining leaves repurposed as specimens in paleography study collections (such as Special Collections’ Rosenthal Medieval Manuscript Collection), and others turned into collectibles or simply discarded.

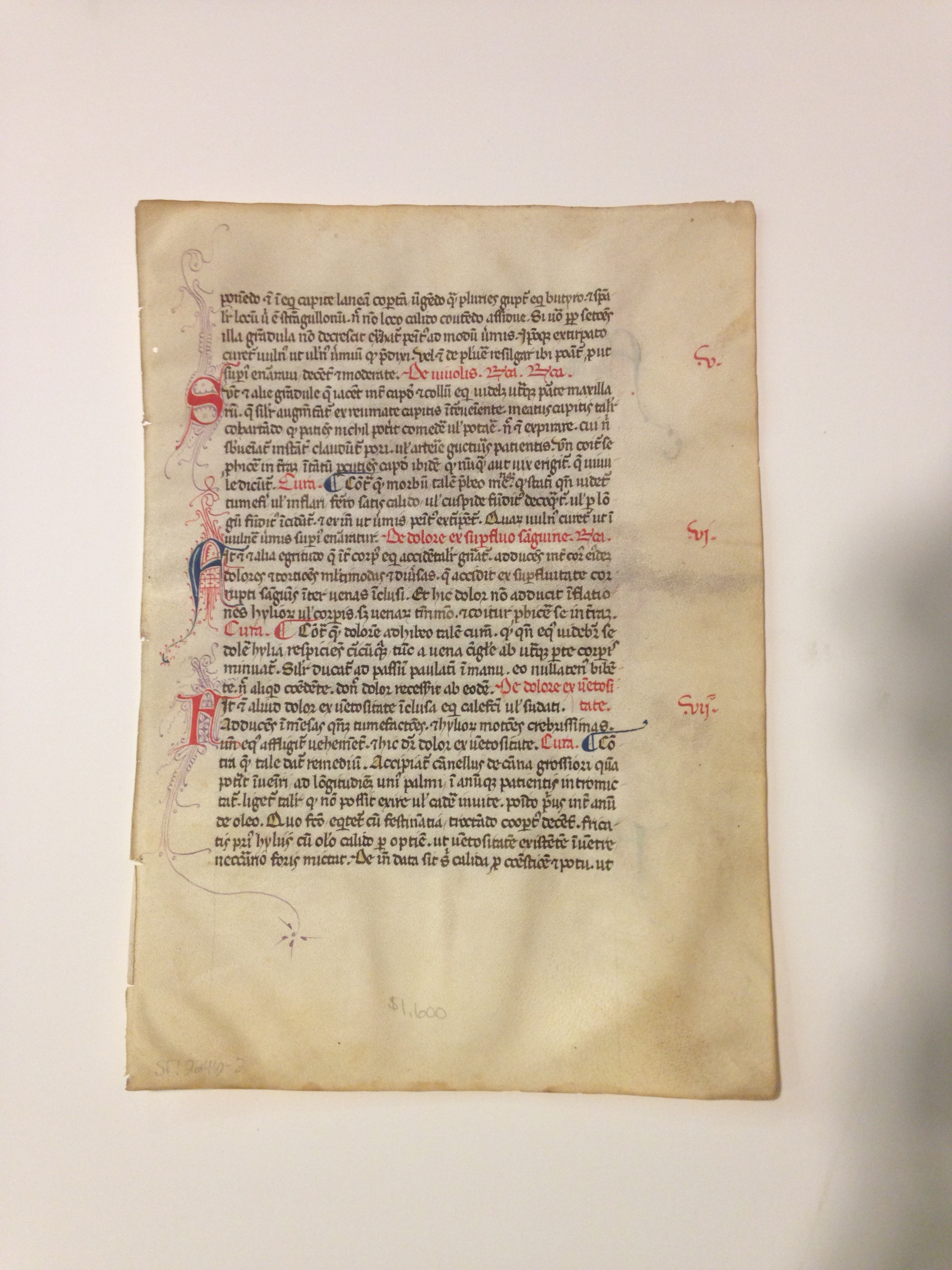

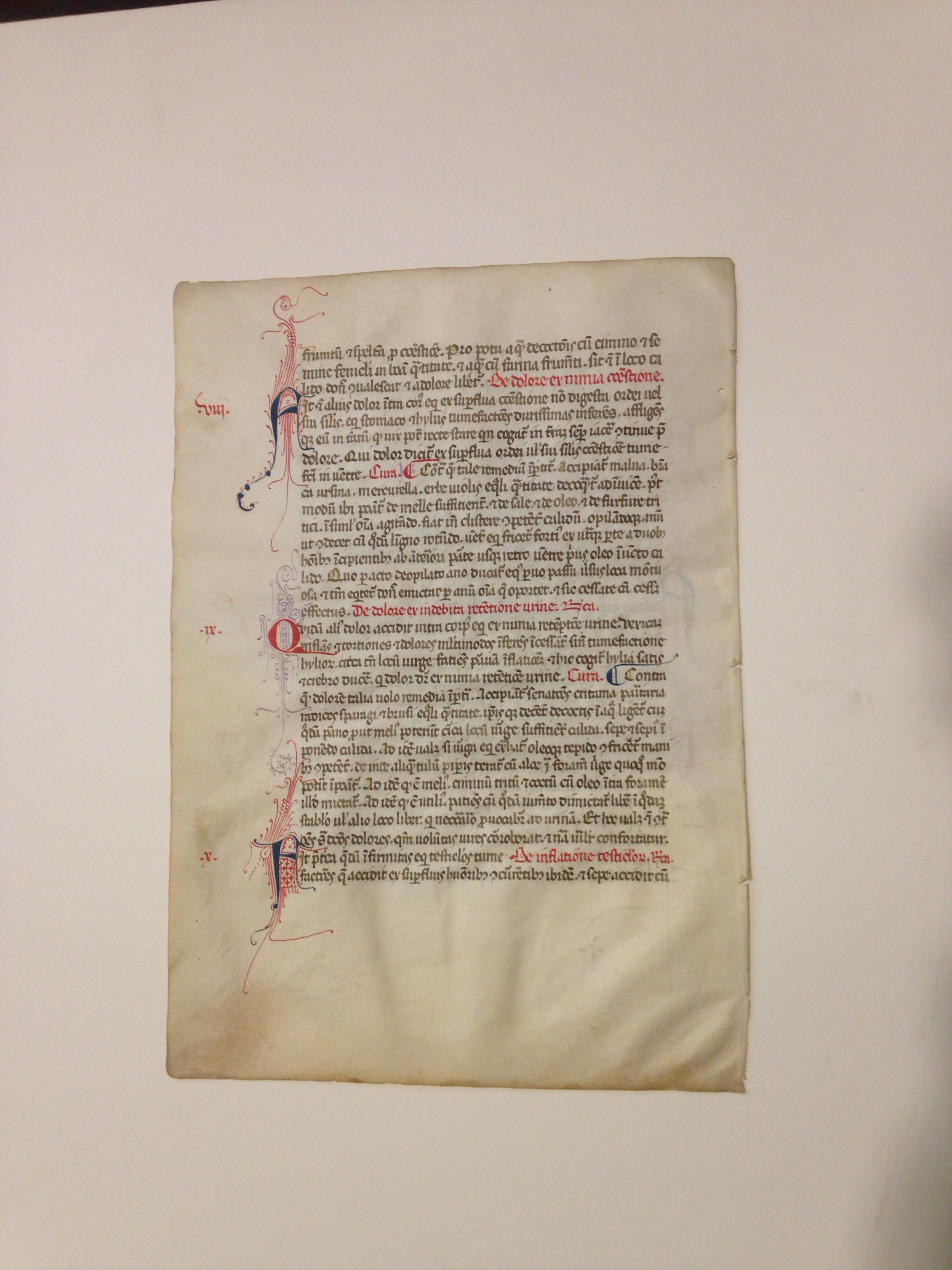

The manuscript leaves are finely rubricated in red and blue with incipits, paragraph marks, chapter numbers in the outer margin, and fine initial letters with penwork extensions in red or purple. (MSS 15703)

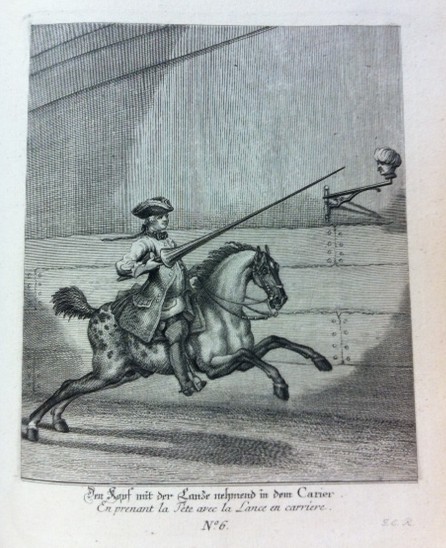

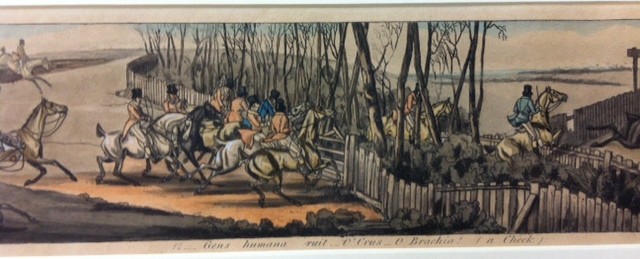

Consider Special Collections’ most recent medieval manuscript acquisition: six finely rubricated vellum leaves from a mid-14th century Latin manuscript, written in Italy, of Giordano Ruffo’s De Medicina Equorum, a treatise on the care of horses originally composed in the 13th century. Secular manuscripts on such topics from the medieval period are of great rarity—indeed, a survey conducted fifty years ago located only 21 manuscript copies of Ruffo’s text, all in European libraries—and we jumped at the opportunity to add these leaves to our Marion duPont Scott Sporting Collection.

Here is what we know about their provenance. In December 2011, 21 leaves from an imperfect copy of Ruffo’s manuscript were offered at a Sotheby’s auction in London. The leaves went unsold but were bought privately following the auction. This past fall we learned of the manuscript when an American bookseller’s catalog, in which eight of the leaves were offered, arrived in the mail. We promptly placed an order for all eight leaves, but two had already been sold. The bookseller subsequently reported that he had originally acquired 11 of the 21 leaves, three of which were sold to two different American research libraries, and two to private collectors in the U.S. and Europe, before U.Va. bought the remaining six. Eleven leaves, five new owners on two continents, with ten leaves still unaccounted for. U.Va.’s interest is primarily in the text, given our extensive holdings on the horse and equestrian sports, though the leaves will also be quite useful for research and instruction in the medieval book, paleography, &c. The other institutional and private collectors presumably were more interested in the leaves as paleographical specimens.

Verso of the manuscript leaf shown above. the chapters concern treatments for certain equine ailments. (MSS 15703)

All parties have benefited from these transactions: the booksellers made money, and the five new owners have acquired useful materials for their collections. But what of the manuscript itself? Any attempt to study the text and its relation to other exemplars has been seriously, perhaps fatally, compromised. (Fortunately, the bookseller kindly sent us study images of the five leaves we missed.) This is a chronic dilemma for any researcher using medieval manuscripts as primary sources. Various efforts are under way to reunite dispersed manuscripts virtually—Manuscriptlink (to which U.Va. intends to contribute its six Ruffo leaves), a project based at the University of South Carolina, is but one example. But these initiatives are unlikely to redress more than a small fraction of the losses already sustained, and still to come. And digital images—it bears constant repeating—can never supersede access to the original artifact.