Charles Brockden Brown’s Wieland, a novel in the Sadlier-Black Collection of Gothic Fiction, gives a tantalizing glimpse into the development of the modern American view of the afterlife. This post was contributed by Emily Pierson, a recipient of the Lillian Gary Taylor Fellowship in American Literature. This fellowship supported her research for her dissertation on the cultural context and impacts of garden cemeteries in nineteenth-century America.

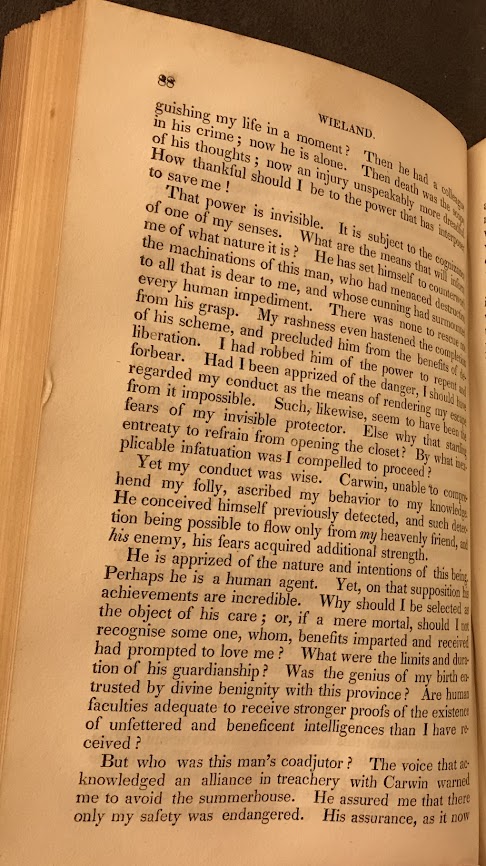

When I proposed a dissertation about cemeteries, I think the last thing my advisors expected was for me to spend several weeks reading novels. The early drafts of that last chapter contained a handful of attempts to link the two subjects, most of which got cut from the final version. Among those works, though, was a particularly interesting Gothic novel called Wieland, or, the Transformation: An American Tale, a remarkably unpromising title when searching for tales of the dead. Wieland, however, presents the reader with a world in which the possibility of the living and the dead interacting with one another is a real one, even if there is a perfectly natural explanation for the tale’s seemingly supernatural events.

The story is that of Clara and her brother, the eponymous Wieland. Following the death of their father, the two encounter a series of mysterious events including phantom voices. Clara presents several possibilities for the origins of these voices: angles, demons, spirits of the dead, even the voice of God. Though ultimately proven to be the voice of a man named Carwin who had briefly made their acquaintance, it was the attempted explanations that were far more interesting to me than the ultimate reveal.

Published in 1811, Charles Brockden Brown presented in his novel possibilities that were outside of the bounds of orthodox interactions between the living and the dead. He begins by calling attention to the family’s adherence to nontraditional theological positions, which are further emphasized in the subsequent chapters as the siblings and their companions muse on the possibilities of interactions between the spiritual and the physical. Before the Fox sisters heard their rappings or the Banner of Light published its first edition, Clara and her brother were pondering whether the mysterious lights and voices they saw and heard might be the spirit of their father. Later on, Wieland proclaims that he will stand as a witness before the bar of Heaven to condemn Carwin. A few lines later, he cries out to his dead wife and children, “I have sent you to repose, and ought not to linger behind.”[1] Two lines of dialogue tease at the possibility that Brown was already viewing the afterlife as an extension of this one, a phenomenon usually discussed in the same breath as the rise of Spiritualism nearly 30 years later.

Brown is not the only author hinting at or explicitly describing an afterlife in which the deceased continue to have remarkably life-like interactions. Walt Whitman seems to speak to the dead, while Harriet Beecher Stowe’s little Eva tells those around her that she hopes to see them in Heaven.[2] Most famously and explicitly, Elizabeth Stuart Phelps’s The Gates Ajar presents a cosmology in which the dead are keen to watch over the living, hope for their reunion, and even play piano. Wieland’s commentary on the bar of his Maker, followed so quickly by commentary about rejoining his dead wife and children, reads as an early participation in this same popular theology of the afterlife.

What, then, does any of this have to do with cemeteries? I was, admittedly, disappointed that Clara is denied the opportunity to attend the burial of her sister-in-law and her children. There are, in fact, no visits to cemeteries in the book. However, those proposals that the afterlife is connected to this one rather than totally distinct from it are precisely the driving force behind cemetery design in the nineteenth century. Family plots gave the opportunity for the living to visit their dead relatives and presented a visual map onto which the living could imagine their own heavenly reunions. Though I found no ghosts or graveyards, Wieland offered a tantalizing look at the development of the mentality that pervaded the nineteenth century and has still left its mark on the way we talk about the living and the dead.

[1] Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Toms Cabin., 2013. 274; Walt Whitman, “Vigil Strange I Kept on the Field One Night,” Leaves of Grass, 1891-1892. See also Whitman’s “Come Up from the Fields, Father.”

[2] Charles Brockden Brown, Wieland, or, The Transformation: An American Tale, 1811. 211; 218.

Toward the final chapters, Clara does in fact visit the family plot on her way to her former house on the Weiland estate, if I recall correctly.