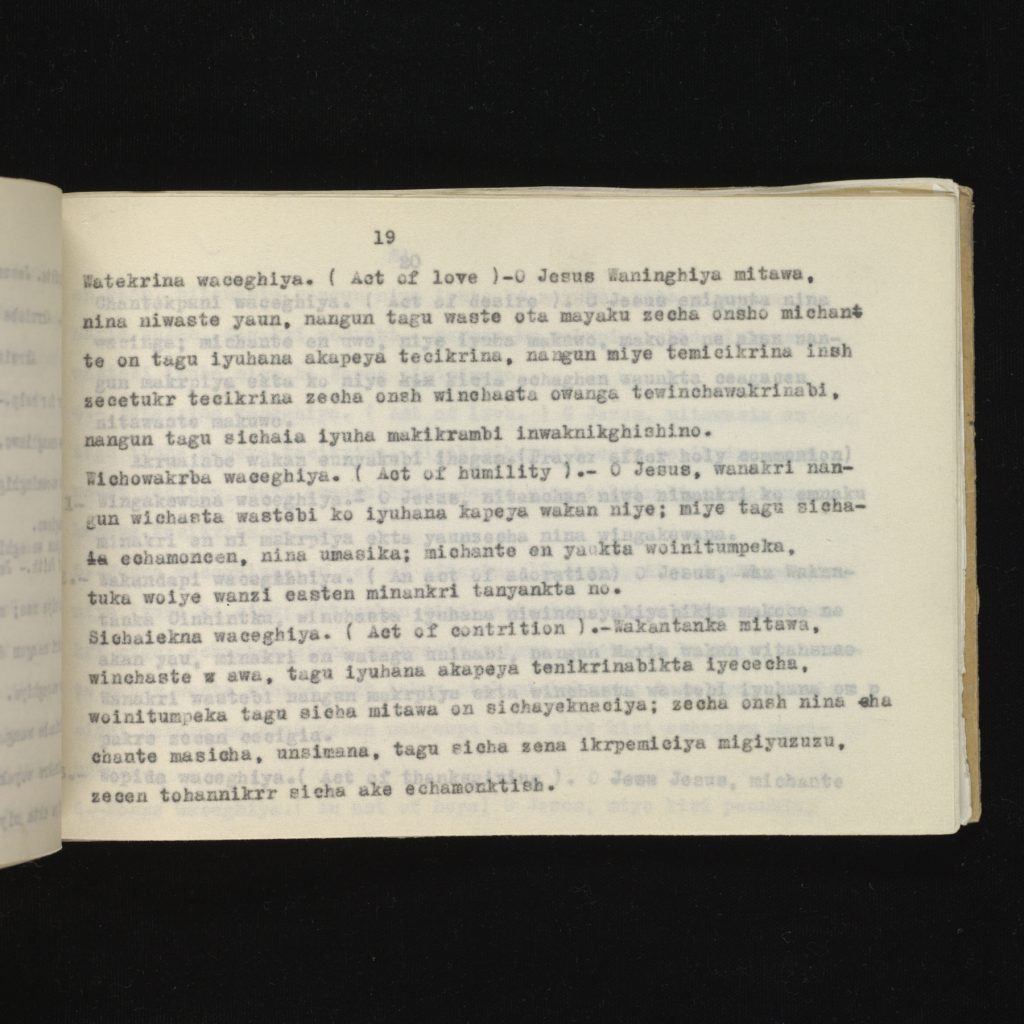

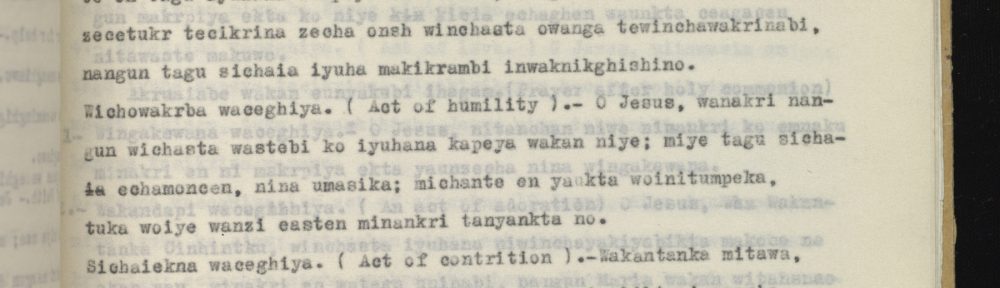

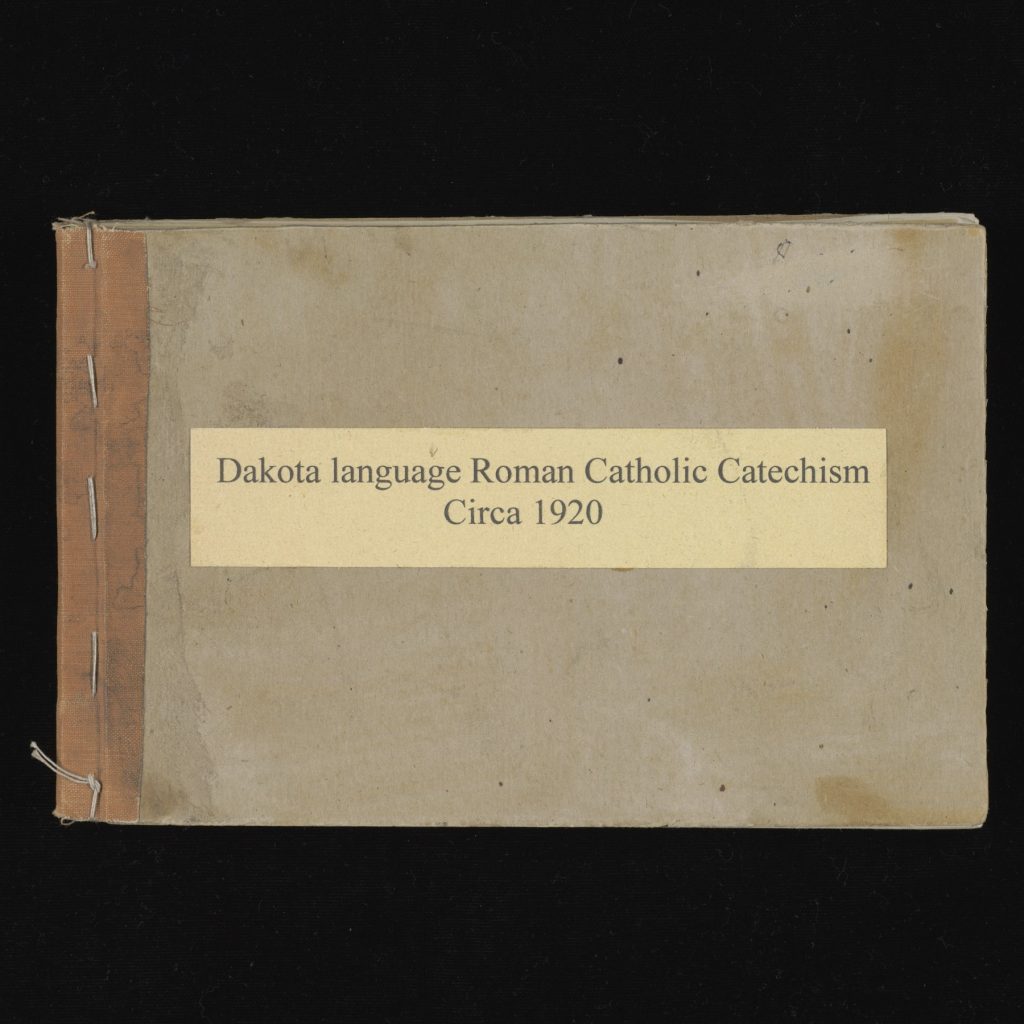

This post is by Ellen Welch, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Manuscript and Archives processor, about a recent acquisition of a Roman Catholic Catechism (MSS 16778), translated in the Dakota language around 1920. It is not known who translated this document, but earlier Christian documents like this one were often translated by missionaries attempting to use the Dakota language to convert Indigenous people to Christianity. They soon learned that the Dakota beliefs would not translate easily to English and Christianity. Instead, these translations have helped to preserve the Dakota language.

The Dakota peoples tribal/rightful lands cover area from present day Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and parts of Canada. They form the Oceti Ŝakowiŋ, the Seven Council Fires which are divisions of the Sioux. Unfortunately, most missionaries and Christian Indigenous residential schools forbade the Dakota people from speaking their language, to the extent of trying to erase their culture and almost making the Dakota language extinct. These translations give us an opportunity to explore the Dakota language and celebrate the culture of the Dakota people.

In addition to these documents, there is now a digital app “Dakhód Iápi Wičhóie Wówapi” from researchers at the University of Minnesota that teaches the Dakota language to online users, particularly the next generation. It is ironic that the missionaries translated the oral Dakota language for the purpose of promoting Christianity—but in the end, it is the beauty of the Dakota language that survives in this archival object. Today, having these historic documents written in the Dakota language—and modern-day online tools to read and speak the Dakota language—gives new life to an important Indigenous community and promotes acceptance and respect for diverse cultures.

Translations of Christian documents into the Dakota language were used to convert people to Christianity. Today they keep the Dakota language alive.

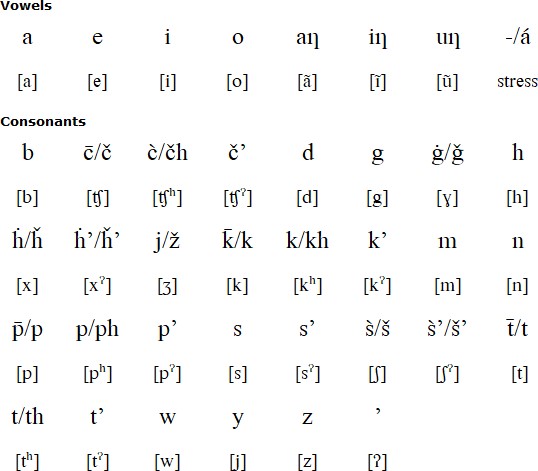

Early missionaries, interpreters, and linguists lived with the Dakota people and studied their oral language (1). In 1834, they began recording and deciphering the Dakota words phonetically and created an alphabet (2). After printing the Holy Bible in Dakota, called Dakota Wowapi Wakan, they produced several reading books, a catechism, a monthly Dakota newspaper, the Book of Genesis, the Gospel of Mark, and by 1865, the New Testament. Their Christian work included studying the Dakota language to identify the meanings of God, religion, and power. The linguists found that these words might seem to have the same meaning on a superficial level, but on closer study, it became clear that the meanings of these words in Dakota were more complex and had different meanings (1).

Harvard postdoctoral College Fellow Gili L. Kliger agrees that the missionaries encountered a range of Indigenous concepts that resisted translation into English. She writes, “It was not just that Wakantanka [great spirit] did not mean “God,” but that the translations exposed the limits of the English language. Wakan has a general meaning of “holy” or “spirit” with no straightforward equivalent in English.” (3) Stephen Riggs, a nineteenth century Christian missionary, also wrote, “The words for “salvation” and “life,” and even “death” and “sin,” did not mean what they did in English.” (4)

Missionaries forced Christianity on Indigenous people while the American government silenced their language, and removed their culture, land, and homes. Yet they were the people whose religions showed respect for other life forms. “Respect and humility are the building blocks of Indigenous lifeways, since they not only lead to minimal exploitation of other living creatures but also preclude the arrogance of aggressive missionary activity and secular imperialism, as well as the arrogance of patriarchy” (5).

Americans have learned so much from Indigenous people. Their languages are sophisticated, and they have deeply spiritual cultures. They have influenced many aspects of American life through agriculture, a federal system of government, over 2,000 words of their language, women’s rights and matriarchal power structures, bravery, and heroic prowess, to name a few. The framework of government in the Iroquois Confederacy is said to have inspired Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and other founders as they wrote the United States Constitution (6).

Moving forward to present day influences, Joe Bendickson, named Šišókadúta (meaning robin red), is a linguistics director (and “keeper of language”) at the University of Minnesota and is teaching Dakota to the students. He agrees that English is unable to fully express meanings of certain Dakota words, especially words describing the spiritual plane. For example, “Wakháŋ Tháŋka’ means something inexplicable and mysterious, and it refers to spiritual concepts such as God.” (7) Šišókadúta grew up without the Dakota language and culture because in the 1950’s, Christian Indigenous residential schools punished and shamed people for speaking it. Three of his grandparents spoke the language fluently. Šišókadúta has been heartened to see more Dakota students interested in learning the language.

Joe Bendickson, named Šišókadúta, is a linguistics director (and “keeper of language”) at the University of Minnesota.

In 2017, Šišókadúta—with help from the nonprofit Dakhóta Iápi Okhódakičhiye (Dakota language for the home, community, and classroom), the Minnesota Indian Affairs Council, and The Language Conservancy—has created the first comprehensive Dakota-language dictionary app. The free app, Dakhód Iápi Wičhóie Wówapi, is meant to bridge the gap between the handful of Dakota speakers left (80- and 90-year-olds) and the younger generation. Wil Meya, of The Language Conservancy said, “We sometimes hear young people say the apps are like having grandma or grandpa in their pocket. And often it is their grandma or grandpa on the app, providing the voice.”

Šišókadúta adds, “The dictionary app itself is just a tool for learning the language, but it’s part of a larger effort to revitalize the language and even create future generations of first language speakers.” (8)

Ava Hartwell, named Oglala Lakota, is one of Šišókadúta’s students. The sixteen-year-old says, “Learning the Dakota language comes with learning the Dakota mindset and ways of our people.” It’s much easier than using the outdated dictionaries that already exist. The last substantive dictionary was published by missionaries in 1852. For Šišókadúta, “it was to learn this language and help bring it back. Revitalize it, grow it. It’s a way to reverse history.” The Dakota language and culture is expressed beautifully. For example, the word trust is wowinape, which means “put one’s hand in another.” The worldview of the Dakota language can be expressed in “mitákuye owás’iŋ,” which means “all are related.” (7) Dakota means “ally” or “friend.” Today, Dakota, which started out as an oral language, goes digital for future generations.

For the atrocities committed by the United States Government against Indigenous people and inspired by the government’s decision to build a pipeline through their land in 2016, veterans came together at Standing Rock Reservation, to ask forgiveness from the Sioux. In gratitude for their language and the positive influences on American culture, organizer Wesley Clark Jr. and other veterans apologized to Leonard Crow Dog and other Sioux leaders:

“We came. We fought you. We took your land. We signed treaties that we broke. We stole minerals from your sacred hills. We blasted the faces of our presidents on your sacred mountain. And then we took still more land. And then we took your children. And then we tried to take your language. We tried to eliminate your language that God gave you and the Creator gave you. We didn’t respect you. We polluted your earth. We’ve hurt you in so many ways. And we have come to say that we are sorry. We are at your service, and we beg for your forgiveness.” (9)

As Amy Gantt, Assistant Professor of Art and Native Studies, at Southeastern Oklahoma State University writes, “Revitalizing the languages is a step toward healing the historical trauma and ensuring survival as a people.” (10) James Mackenzie, University of Arizona Department of Teaching, Learning & Sociocultural Studies, adds, “By having connection to their Indigenous languages, people better understand who they are, which can promote better health. This only affirms an understanding long shared by our elders and ceremonial practitioners: language is medicine. In this sense our languages can literally heal us.” (11)

Sources:

1. Missionaries and linguists mentioned are Gideon Pond (1810-1878) (Matohota-grizzly bear), his brother, Samuel Pond (1808-1891), (Wanmdiduta-the red eagle), Dr. Thomas S. Williamson (1800-1879), Stephen Return Riggs (1812-1883), Joseph Renville (1779-1846-a son of a Dakota woman), and Samuel Dutton Himnan (1839-1890). The Manga Writer. Dakota Love. “The History of the Dakota Bible (Dakota Wowapi Wakan).” The ForwardsBackwards Blog. June 26, 2019.

2. Riggs, Stephen. “The Minnesota Constitution in the Language of the Dakota.” Translated by Steven Riggs. (1858)

3. Kliger, Gili. “Translating God on the Borders of Sovereignty.” American Historical Review. Volume 127. Issue 3. September 2022.

4. Riggs, Steven, R. “Mary and I: Forty Years with the Sioux.” Chicago. W. G. Holmes. March 1889.

5. Forbes, Jack, D. “Indigenous Americans: Spirituality and Ecos.” Daedulus. Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Fall 2001.

6. Cavallari, Dan. “How Has American Culture Been Influenced by Native American Culture?” United States Now. April 23, 2023.

7. Forgrave, Reid. “Joe Bendickson Šišókadúta.” Star Tribune February 25, 2023.

8. “New Dakota Language App Helps Bridge Gap” Minnesota Reformer. March 12, 2023.

9. Veterans Ask for Forgiveness at Standing Rock

10. Gantt, Amy M. “Native Language Revitalization: Keeping the

Languages Alive and Thriving” Southeastern Oklahoma State University

11. Mackenzie, James. “Addressing Historical Trauma and Healing in Indigenous Language Cultivation and Revitalization.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 1–7. doi:10.1017/S0267190521000167 Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 February 2022.

This was just so informative and enlightening. Thank you!!!