This week we are pleased to feature a guest post from Nicholas Shangler, Lecturer of French at Longwood University in Farmville, Virginia.

Dr. Shangler graduated with a Ph.D. in French from the University of Virginia this past May 2013. While in graduate school, he worked with rare books as a student employee in Digital Curation Services at the University of Virginia Library, and while doing so, found a series of books by Henri Estienne that would become central to his dissertation work.

***

During my first semester of graduate school, I quickly realized that I needed a part-time job. Serendipitously, Digital Curation Services was seeking someone to assist with the digitization of the Gordon Collection, an impressive holding of primarily sixteenth century French books, at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. I didn’t know it then, but that job would influence the course of my graduate career and beyond, leading me to specialize in Renaissance literature. The digitization process involved perusing the books in the Gordon Collection, selecting one, and scanning it page by page. Although admittedly tedious at times, the process allowed me to spend hours each day becoming acquainted with fascinating materials more profoundly than I ever would have otherwise. Many of the works are not exactly canonical, affording me a richer experience of Renaissance French culture and literature than I’d previously been exposed to in classes.

A section of the Douglas H. Gordon Collection of French Books stacks. (Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

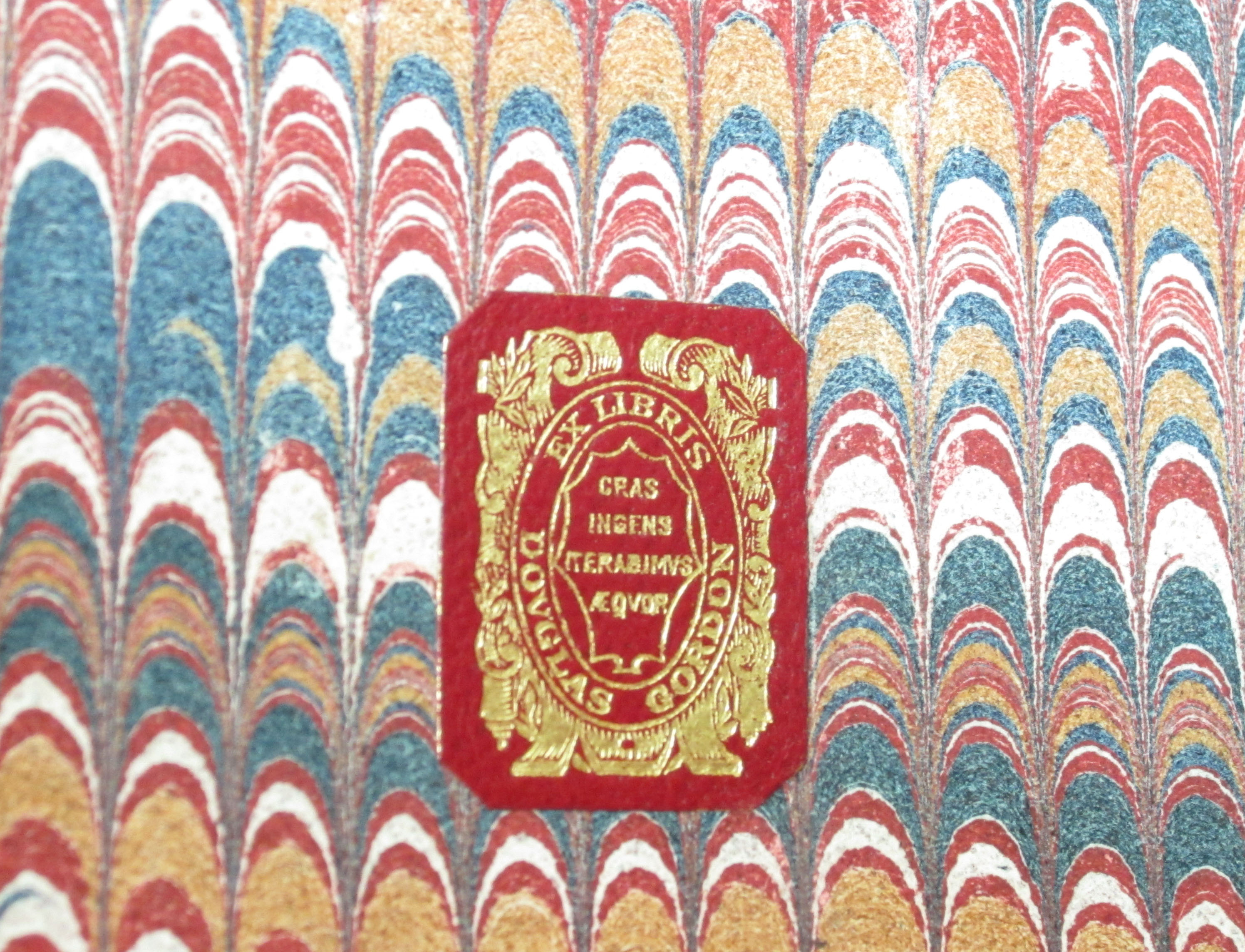

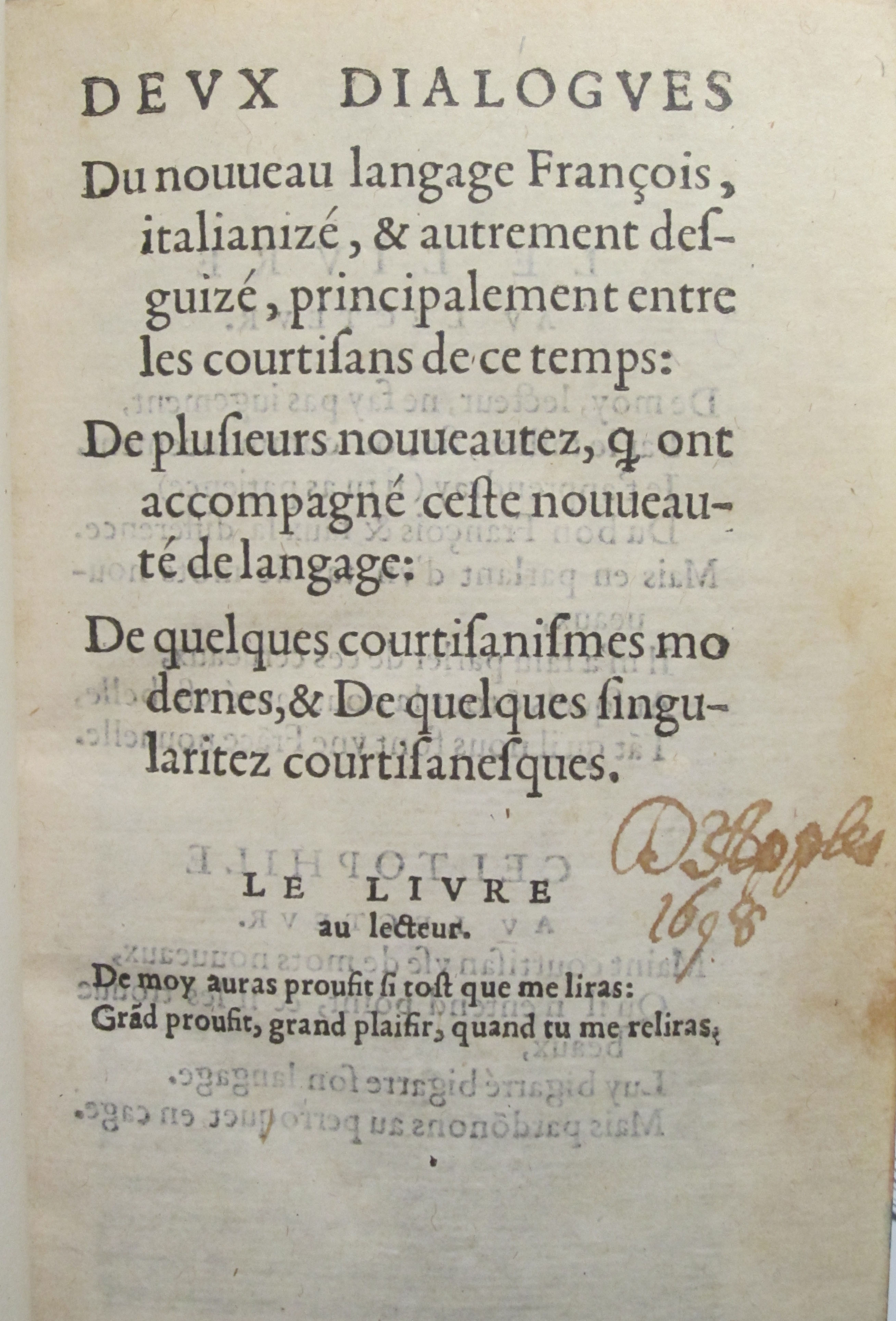

One curious work that I spent some time considering was Deux dialogues du nouueau langage françois (1578) by Henri Estienne. It intrigued me with its descriptions of French words being chopped in half and “stuffed” with Italian words (inserted between the two ends of the original French words). What?! Then the author claimed that the French language descended from Greek, not Latin. Clearly this guy was crazy. I put it down and chose other works to digitize. But apparently it stuck with me. Five years later, while drafting my dissertation prospectus on French language innovation in the Renaissance, I recalled these strange dialogues. I returned to Special Collections and paid Monsieur Estienne a visit.

Henri Estienne’s Deux Dialogues du Nouveau Langage Francois, 1578 (Gordon 1578 .E78. Douglas H. Gordon Collection of French Books. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

France and Italy experienced a mutual cultural and linguistic intertwining beginning in at least the early medieval period. The influence of the Italians intensified with the marriage of the French prince, Henri II – son of François I – to Catherine de Medici, in 1533. The ascension of Henri II to the throne in 1547 brought increasing numbers of Italians not only into France, but into the folds of the French Court. Many courtiers embraced the growing Italianism and affected a language heavily characterized both by Italian words and by French words recomposed so as to incorporate fragments of Italian. However, a number of prominent voices discouraged their French countrymen from having anything to do with the Italians, urging instead greater respect for French national culture. Among those who began to protest against the intrusion of Italianism in France, and particularly with regard to language, a certain Parisian printer distinguished himself by his fervor and for his compelling articulation of the argument in support of the purity of French.

Henri Estienne (1528-1598) was destined to participate in the battle over language. The son of Robert (1503-1559), a renowned printer and scholar, Estienne developed from a young age a curiosity and love for languages and books. He mastered Latin, Greek and Italian, and devoted a significant amount of work to translating, editing, publishing and/or collating essential classical texts. During the final two decades of his life, from the mid-1570s until his death, Estienne undertook two original editions of the Greek New Testament accompanied by his own critical commentary.

Henri Estienne’s polemic against the Italianized French employed by French courtiers appears in three separate but related works. Together they form a sort of trilogy, each attacking various aspects of the central problem. The first, Traicté de la conformité du language françois avec le grec (1565), denies the superiority of Italian by belittling its roots. Estienne claims in his preface that the Italian language owes a far greater debt to French than does French to any Italian heritage. He supports his argument by advancing the idea that French descends directly from Greek and has more in common with Greek than any other language. Since everyone universally recognizes Greek as the greatest language in history, French must therefore be the second greatest. Italian, on the other hand, is but the paltry progeny of Latin. Estienne decries the recent linguistic inventions of the Italianizing courtiers and instead longingly praises the true French language “pure and simple, showing nothing of artifice, nor of affectation: that which Sir Courtier has not yet changed according to his tastes, and which has nothing borrowed from modern languages” [“pur et simple, n’ayant rien de fard, ni d’affectation: lequel monsieur le courtisan n’a point encore changé à sa guise, & qui ne tient rien d’emprunt des langues modernes.”] (Estienne, Conformité, preface, Vvo)

Henri Estienne’s Traicte de la Conformite du language francois auec le Grec, 1565. (Typ.E77 1565E. Stone Typography Collection. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Estienne continues the attack where he left off with the 1578 publication of the Deux dialogues du nouueau langage françois. The book opens with a series of poems that set the stage for the debate to follow. In the first of the two dialogues, Estienne posits an exchange between a character named Celtophile (“lover of France”), whose role is to prosecute the case against the Italianized French, and Philausone (“lover of Italy”), who frequents the Court and is charged with defending the practice. Naturally the jury is rigged in favor of Celtophile, with the accused found guilty even before the opening gavel. The two interlocutors find themselves at an impasse at the close of the first dialogue. They agree to reconvene the next morning to continue their discussion, and to go together to consult a third party, Philalethe (“lover of Truth”). Over the course of the second dialogue the topic of their argument gradually progresses to whether French or Italian, considered separately rather than in their blended form, is the greater language. Once Philalethe joins the conversation he promptly dismantles all of Philausone’s reasoning, according an unconditional victory to the French language. Still, Philausone refuses to concede. The book ends with Philalethe promising to demonstrate further the dominance of the French language at a later time.

Keeping Philalethe’s promise, the following year – 1579 – Henri Estienne published De la précellence du langage françois, which he dedicated in the preface to King Henri III. Though this work stands as a sequel to the Dialogues, Philalethe disappears and Estienne offers the book in his own voice using his real name, opening with a poem entitled “H. Estiene aux François.” Here he broadens the scope of his attacks, no longer limiting himself to rebutting the use of Italianisms at Court. Alluding to his own Conformité, he reiterates his claims of the self-sufficiency of French with regard to other languages, particularly Italian. Most of Estienne’s logic is unsound. He persists in relying upon his fallacious etymologies relating French to Greek, that he first sketched out in the Conformité, and then states that any words that seem equivalent between French and Italian are the result of Italian borrowing, rather than a common Latin heritage.

Henri Estienne’s Project du Livre Intitulé De la Precellence du Language Francois, 1579. (Gordon 1579. E78. Douglas H. Gordon Collection of French Books. Image by Digitization Services )

Estienne ridicules the changing pronunciation of certain words, and presents his vision of the resulting confusion of words and objects in ways that give his reader to understand the gravity of the situation. For instance, in the Dialogues, he condemns the changed pronunciation of oi into e. The examples that he chooses – including “françois” (Frenchman) to “français” and “roine” (queen) to “reine” – underscore the danger of allowing the courtiers’ language to insinuate itself into the formerly pure French. Not only does the new form of the word for “queen” risk signifying a frog instead, but the pronunciation of the very word indicating national belonging is changing.

Such a world is unstable and proved frightening to Estienne. Estienne suggests even from the outset that the new words and those who are using them in new ways are already changing France itself. The Dialogues opens with the poem, “The Book to the Readers” [“Le Livre aux Lecteurs”], which offers the warning that there are those for whom “in everything novelty is beautiful, / So much so that they are making us a new France” [“en tout la nouveauté est belle, / Tant qu’il [sic] nous font une France nouvelle”] (Estienne, Dialogues). These worries transcend a mere discussion of language, and extend into the realms of politics and society. Estienne’s works suggest that changes in language will precipitate changes in reality. Although his focus is ostensibly linguistic, his motivations spring from deep political concerns about the future of his native France.

I suppose Henri Estienne would be relieved to know that the French language I was studying when I discovered his works in 2004 ultimately survived the encroachment of Italian. His works and the many others of that era housed in the U.Va. Special Collections are all perfectly comprehensible to French speakers of today, despite the occasional variation in spelling and usage. However, browsing current French-language social media posts online, I suspect that there would still be fodder aplenty for a reincarnated Estienne to pen yet another series of polemical treatises, though the target would no longer be Italian. As it happens, in 1964, René Étiemble published Parlez-vous franglais?, a work linking patriotism and linguistic purism in which he approvingly references Estienne and cites passages from the Précellence du langage françois. Indeed, these old rare books continually prove to be far more relevant to modern ideas than one might first imagine.