This week we are pleased to feature the second guest blog post from graduate curatorial assistant Kelly Fleming, who will be sharing selected treats from our upcoming exhibition, “Shakespeare by the Book,” over the coming months. The exhibition opens February 22, 2016.

My first two weeks at Special Collections were spent hoisting hulking ledgers from the stacks and placing them gently onto cradles to investigate whether two early booksellers in Virginia sold Shakespeare. After the first day, I found my legs covered in wisps of binding and my hands stained with “red rot” from the ledgers’ leather bindings. Thank goodness for gloves.

Here’s what my gloves looked like after several ledgers. Imagine what my bare hands looked like before I put them on.

I combed through the account books of Bell & Co., a printer in Alexandria, Virginia active in the nineteenth century and the Virginia Gazette, a newspaper and printer active in Williamsburg, Virginia in the eighteenth century. My eyes sought any spelling variation of the name “Shakespeare” amidst endless purchases of envelopes and paper. Despite our modern perception that Shakespeare’s works are “classics” and that he is a father of the English language, his place in the literary canon was yet to be defined in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. As my findings attest, Virginians chose to read a myriad of other things more frequently than Shakespeare.

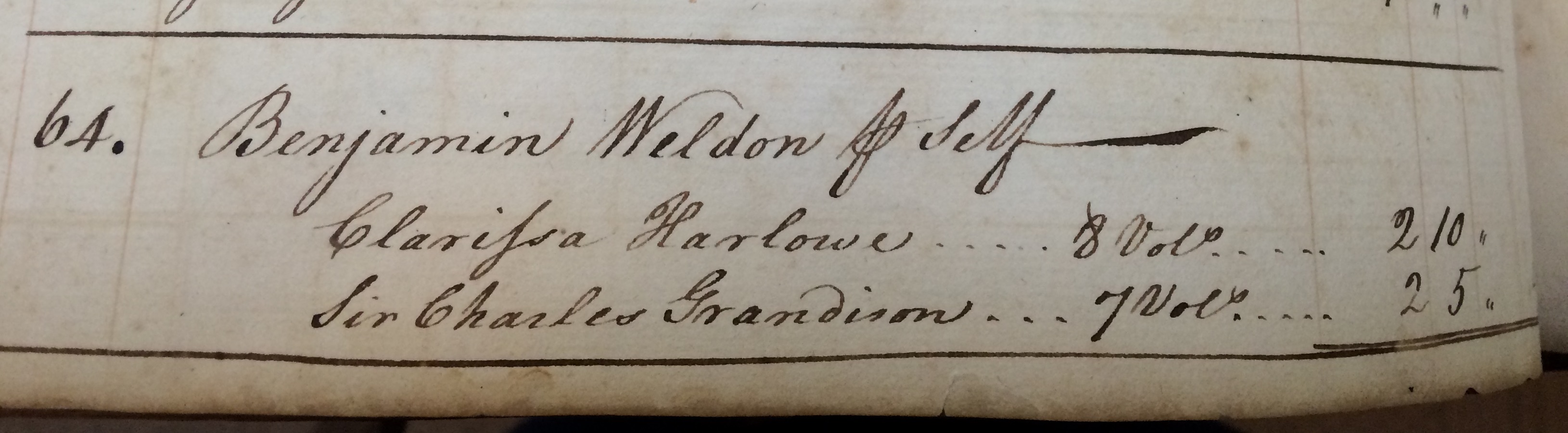

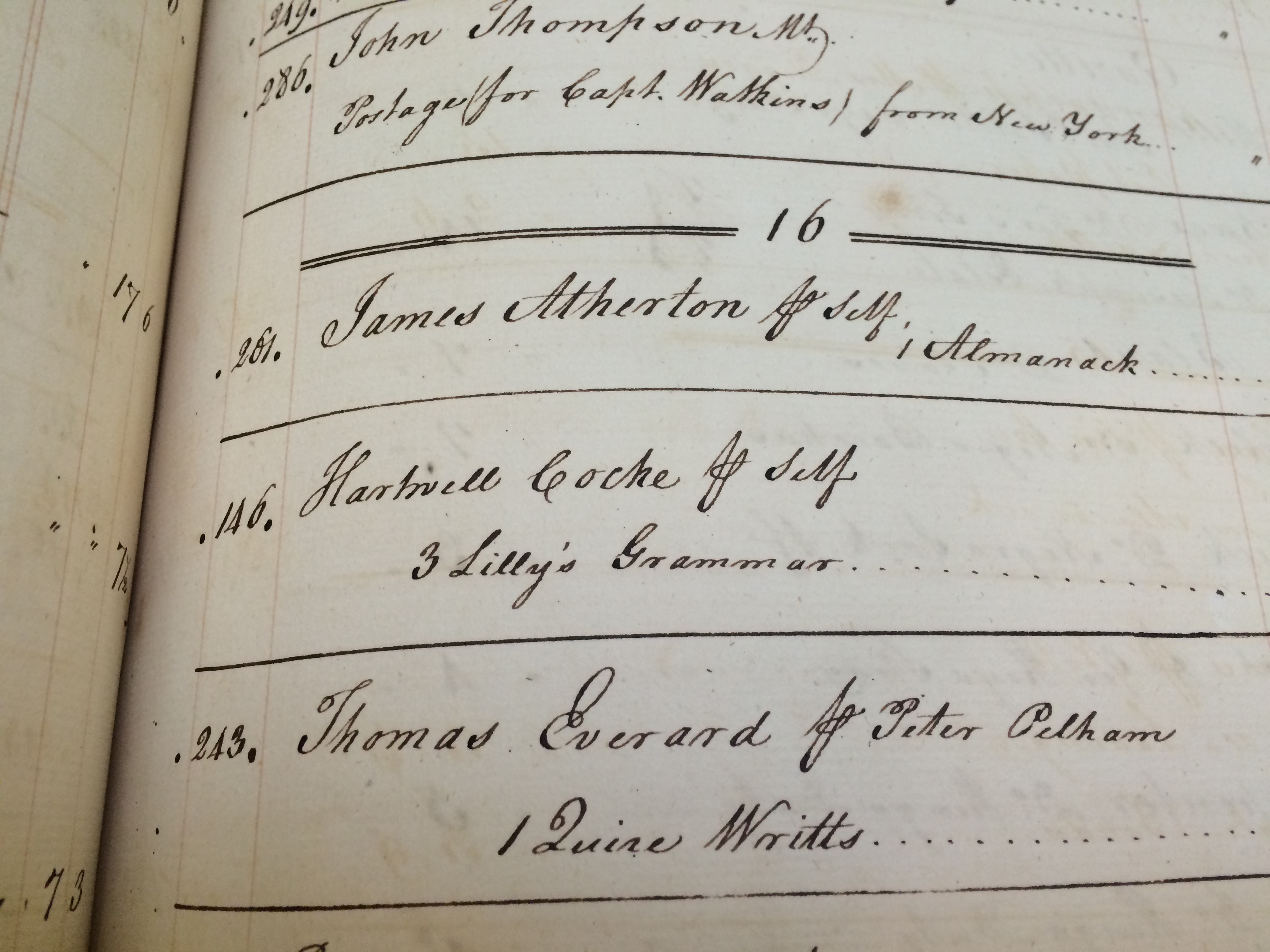

Only one copy of Shakespeare was sold by the Virginia Gazette in the years 1750–1752 and 1764–1766. Even though David Garrick was busily working to increase the popularity of Shakespeare in London at this time, the colonies seem to have been a step behind. Since Williamsburg was home to the Virginia legislature and the College of William & Mary, it is not surprising that the books sold by the Virginia Gazette were largely educational: Latin grammar textbooks, dictionaries, and religious texts like the Book of Common Prayer. Despite the fact that Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (a book the Virginia Gazette also sold) marks Shakespeare’s works as the first usage of many English words, students were not studying Shakespeare. The education system in the eighteenth century trained students (that is to say, young men) in what they considered the “classics”: philosophical and literary texts from ancient Greece and Rome. When students did read literary texts in English, it seems that they read English epics, which use classical elements to describe contemporary England. The epic works of Milton, Dryden, and Pope, for example, appear numerous times in the accounts of the Virginia Gazette. In addition to English epics, we find our copy of Shakespeare alongside another genre excluded from the education system: the novel. In the ledger in our exhibition, we find popular English novels such as Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa and Tobias Smollett’s Roderick Random.

![Joseph Hutchings purchased 8 volumes of of Shakespeare "for [his] self" (MSS 467).](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/theobalds_shakespeare.jpg)

The Virginia Gazette records show Joseph Hutchings purchasing 8 volumes of Shakespeare “for [him] self” (MSS 467).

Alongside Shakespeare in the Virginia Gazette records are two of Samuel Richardson’s novels, “Clarissa: Or, the History of a Young Lady” (1747-8) and “The History of Sir Charles Grandison” (1753). (MSS 467)

Alongside Shakespeare in the Virginia Gazette records are many educational texts such as Lilly’s Latin Grammar. (MSS 467)

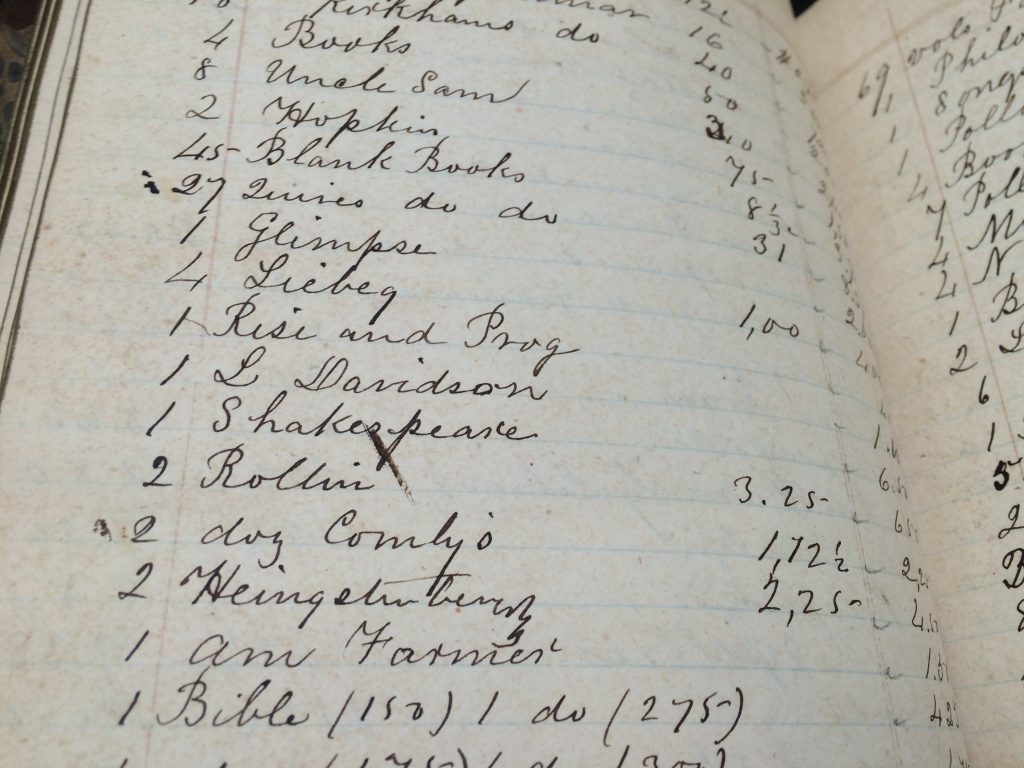

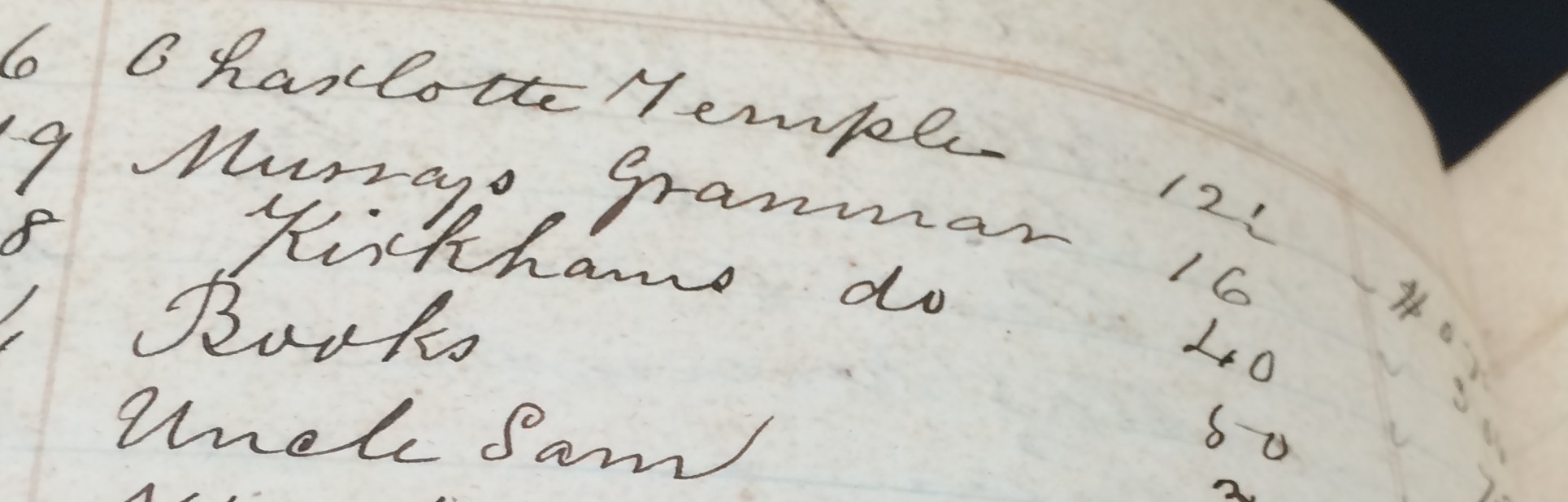

Thanks largely to new performances of Shakespeare plays, Garrick’s Shakespeare Jubilee, and new editions of Shakespeare works in the eighteenth century, Shakespeare’s words come alive by the nineteenth century. The accounts of Bell & Co. reflect this increasing popularity. I found seven copies of Shakespeare sold at Bell & Co. over the course of the nineteenth century (1809–1899). The specific ledger we are using in the exhibition shows Shakespeare alongside Susanna Rowson’s novel Charlotte Temple, Wordsworth, Cooper’s Virgil, and the Bible.

Bell & Co. sold Shakespeare for “6.50.” Different types of currency were in use in the colonies at this time. Without further research, all we can tell from this record is that it is expensive and suggests that the reader bought a multi-volume set (MSS 2989).

On the same page as Shakespeare, Bell & Co. recorded the purchase of Susanna Rowson’s novel “Charlotte Temple” and two grammar books. (MSS 2989)

Finally, in the twentieth century, Shakespeare begins to be studied and to be studied as a father of the English language. Today, Shakespeare is probably the most often memorized, most often recited English author in schools. I still can recite the famous speech of Titania’s from A Midsummer’s Night Dream that I memorized in the tenth grade and that begins “Set your heart at rest.” But as the exhibition at the Special Collections Library will show us in February, our hearts do anything but rest when we hear the heartbeat of Shakespeare’s iambs, even four hundred years after his death.