In 1918, a new strain of influenza swept around the world. Before it was done, it had killed approximately 30 million people. In the United States at least 750,000 died in only a few months—the equivalent today of almost 2.5 million. When the epidemic arrived in Virginia, 25% to 30% of the population caught the virus and thousands died, including six U.Va. students and a nationally known faculty member.

Addeane Caelleigh is researching the epidemic in Virginia. When she retired recently from the School of Medicine, she immediately began work in archives and libraries, including the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library and the Historical Collections archive in the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library. “I’ve long been interested in how communities respond in extreme situations, such as natural disasters and epidemics,” she explained.

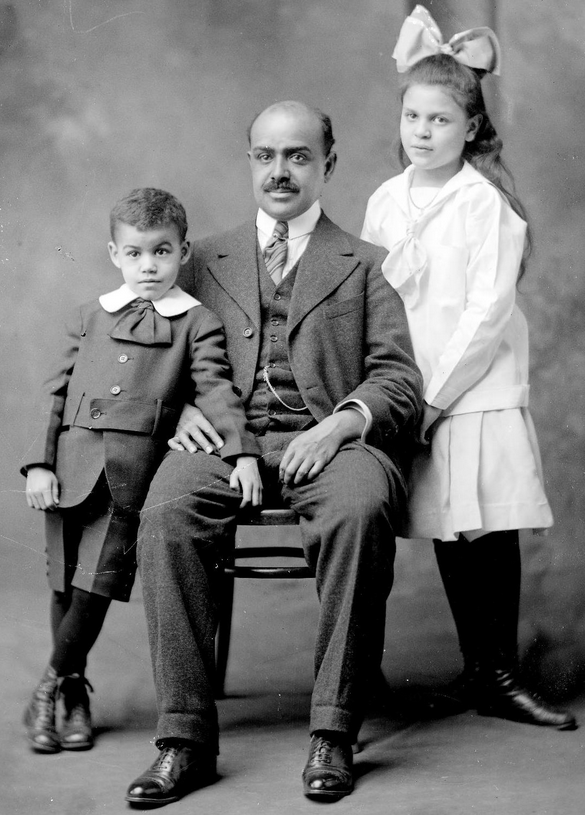

Addeane uncovered emotionally powerful manuscripts here in Special Collections, including handwritten letters about family experiences with the disease and official documents about U.Va.’s response to the crisis. She also found a photograph of George F. Ferguson, M.D., an African-American physician in Charlottesville who cared for many during the epidemic.

Dr. George F. Ferguson poses with his children in this family portrait by Charlottesville photographer Rufus Holsinger taken a few years after the flu crisis, in 1922. (MSS 9862, available online).

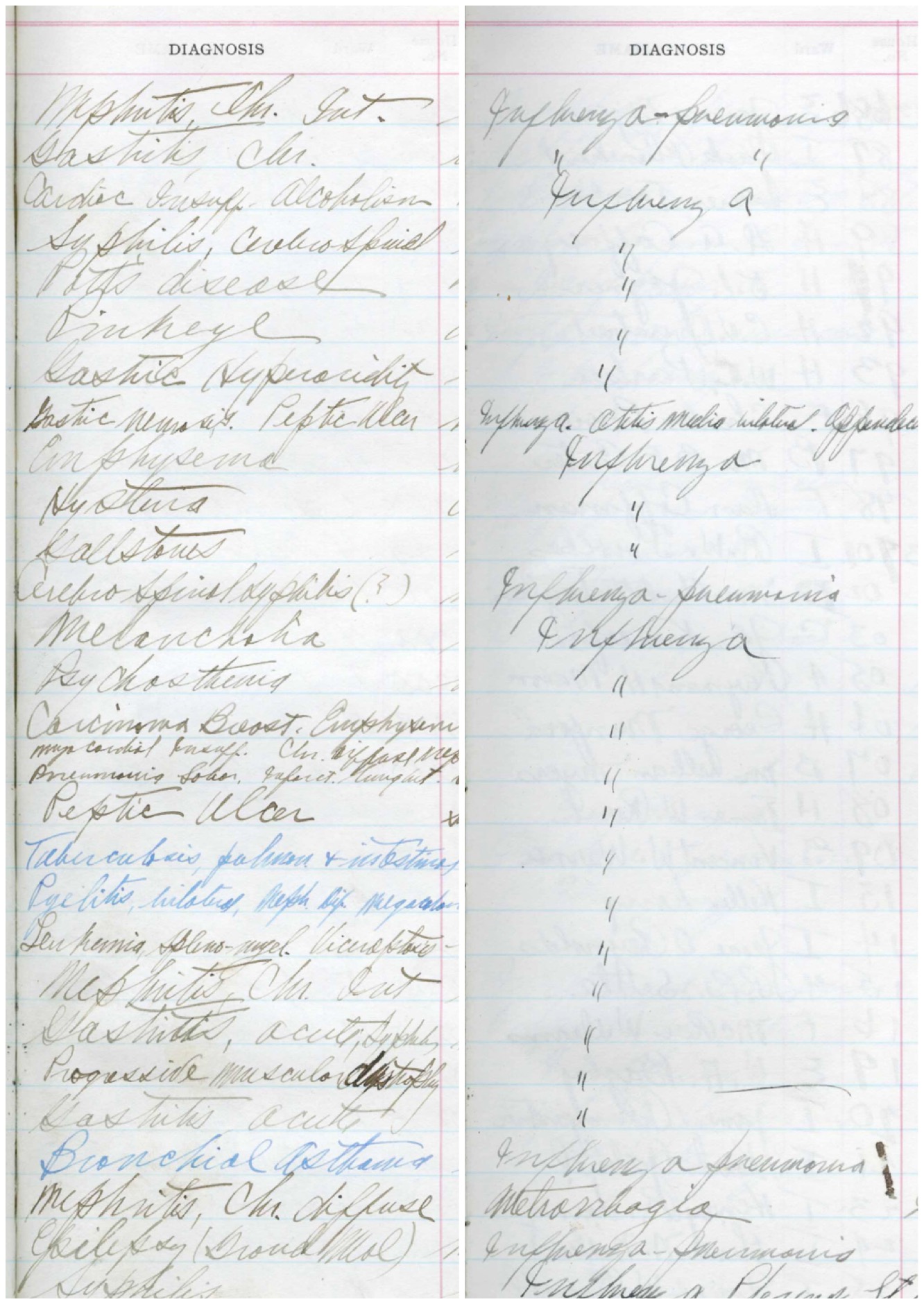

Notably, Addeane is among the first researchers to have the opportunity to view a UVA Hospital admissions ledger for 1915-1919, where she can track the diagnoses—and deaths—of patients from around the region.

On the left are diagnosis entries in the hospital ledger from 1917, before the influenza outbreak. On the right, an entry from 1918, showing starkly the epidemic’s impact on the community.

Until recently researchers could not use the ledger because of restrictions imposed by the Health Insurance and Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA), which protects the confidentiality of patient information. In 2014, Congress allowed an exception for historical research, and Ms. Caelleigh has collected invaluable data about hospital patients with influenza, helping to expand understanding the epidemic in Virginia. Studying issues of the Daily Progress, which is available digitally through UVA Libraries, enables her to reveal details of the community’s responses.

Overall, her research is building a picture of both the epidemic and the community’s responses. “Interestingly, as deadly as the epidemic was locally and nationally, it seems to have dropped out of sight in local memory,” she noted. Her research adds an important understanding of how a major event can unite a community.