This summer the French frigate Hermione—a reconstruction of the vessel which, in 1780, brought the Marquis de Lafayette back to the United States with welcome news of French aid, and which then helped to secure final victory at Yorktown in 1781—made a triumphal voyage to the United States. Built in France between 1997 and 2012 at a cost of over $20 million, the Hermione—measuring 213 x 37 feet, its center mast reaching 177 feet—takes pride of place as France’s grandest “tall ship.” After arriving at Yorktown, Va., to a gala reception on June 5, the Hermione stopped at a dozen ports of call along the eastern seaboard before departing for France on July 18.

As a memento of the Hermione’s visit, the U.Va. Library’s devoted friend and generous supporter Albert H. Small has presented us with a photograph of the reconstructed ship at anchor in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. Mr. Small’s gift prompted us to search Under Grounds for rare books, manuscripts, and other artifacts relating to Lafayette, and we located much of interest! Following is a brief sampling of what Lafayette enthusiasts will find in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

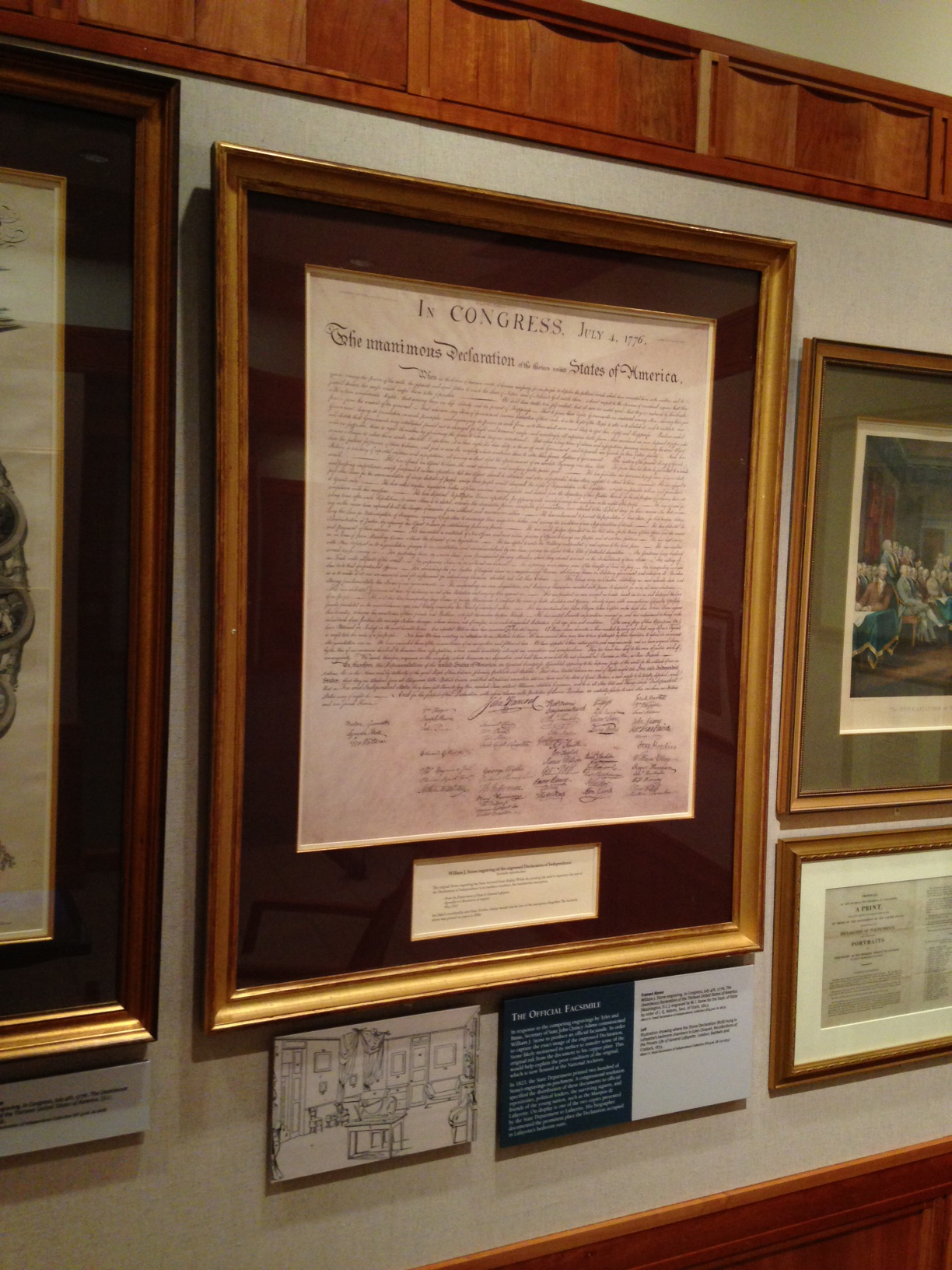

The Marquis de Lafayette – Albert H. Small copy of the 1823 “Stone” facsimile of the Declaration of Independence, on display in the Small Special Collections Library’s Declaration Exhibition Gallery. (KF4506 .A1 1823; Gift of Albert H. Small)

Perhaps pride of place should go to Lafayette’s own copy of the Declaration of Independence—the document he devoted his life to defending and disseminating. During Lafayette’s triumphal tour of the United States in 1824-1825, he was presented with an official full-size engraved facsimile, printed on vellum, of the original Declaration now on display in the National Archives. Lafayette treasured this copy of the “Stone printing,” hanging it in his bedchamber after returning to France. Eventually acquired by Albert H. Small, Lafayette’s copy now resides at U.Va., where it forms part of Mr. Small’s superlative Declaration of Independence collection. Visitors may view it (or rather, for conservation reasons, an exact facsimile of the original) in the Small Special Collections Library’s permanent exhibition of highlights from Mr. Small’s collection.

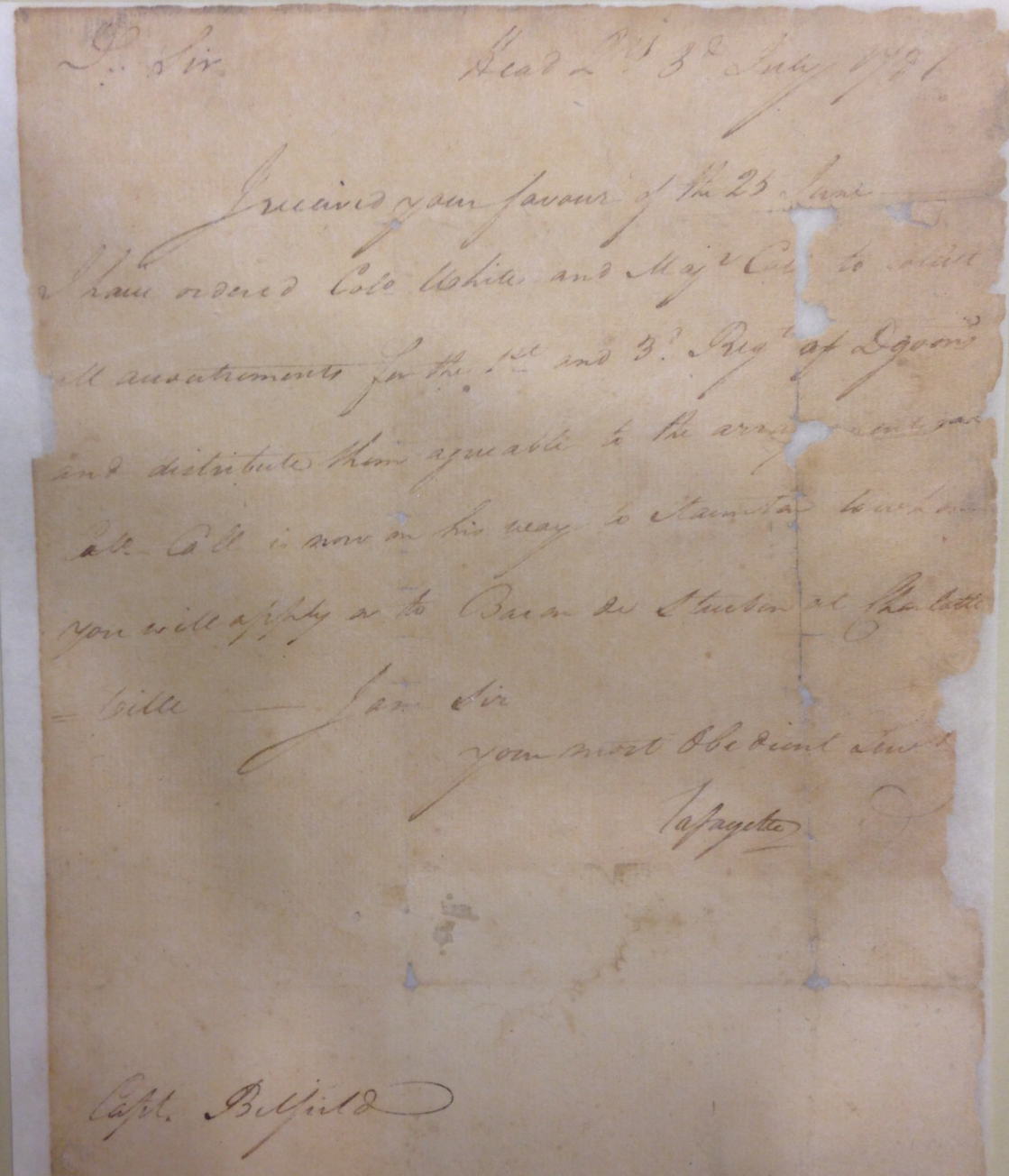

Arriving in the U.S. in 1777 as a newly commissioned officer, the 19-year-old Lafayette soon won the respect and friendship of George Washington while contributing significantly to the American cause. In the early summer of 1781, Lafayette played a critical role in skirmishing with British forces in Virginia until Washington had time to spring his trap at Yorktown. On July 3, 1781, Lafayette sent the orders shown above to a Capt. Belfield at Staunton, Va., also noting the presence of Baron von Steuben in Charlottesville.

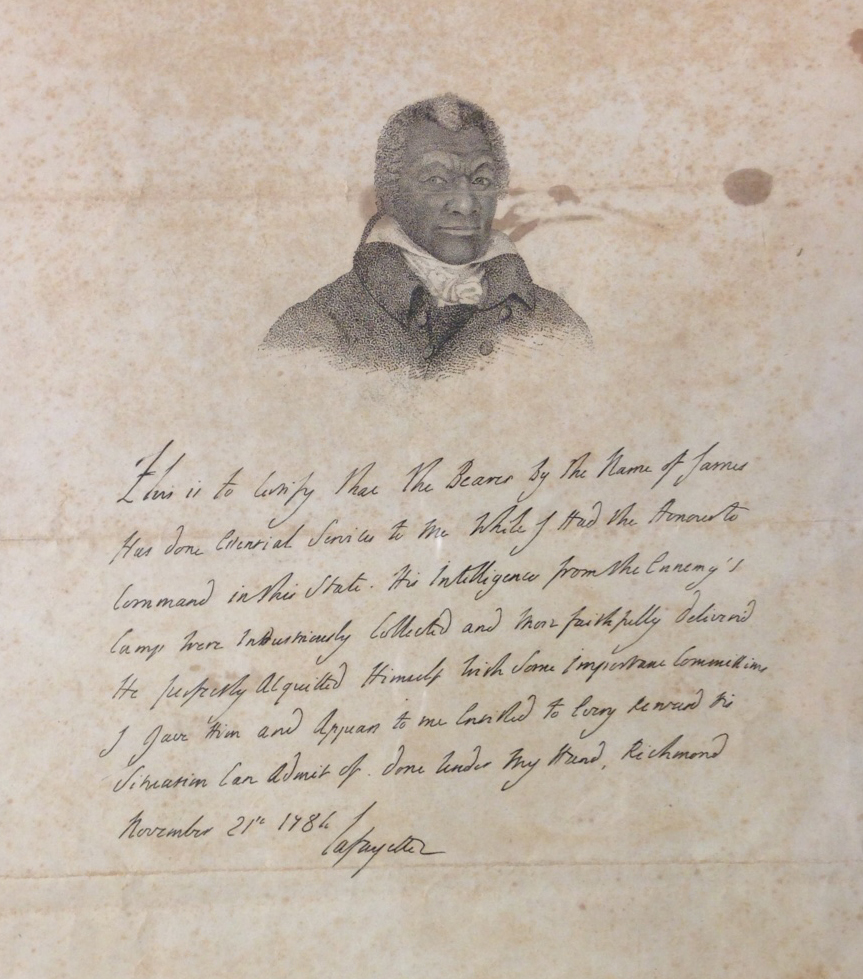

An engraved facsimile, ca. 1824, of Lafayette’s 1784 testimonial letter on behalf of James Armistead Lafayette, with added portrait. (Broadside 1824 .L25)

Another Virginian in Lafayette’s service was James, a slave permitted by his master to serve as an American spy behind British lines by posing as a fugitive. In 1787, with his owner’s support and a testimonial letter from Lafayette, James was freed by the Virginia Assembly and took the name James Armistead Lafayette. When Lafayette returned to the U.S. in 1824, his kindness to James—and his ardent support for the as-yet-unrealized ideal that “all men are created equal”—were commemorated in an engraved print bearing James’s likeness above a facsimile of Lafayette’s testimonial letter.

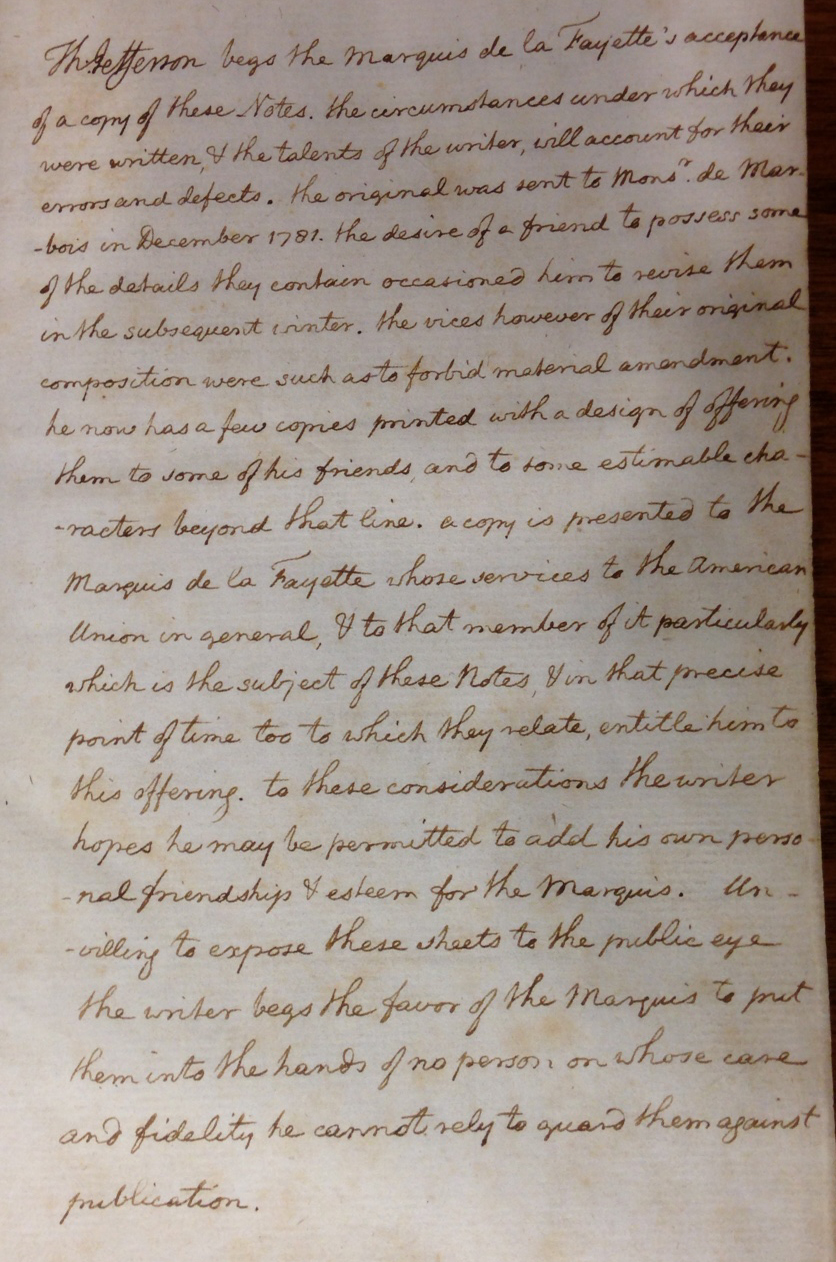

Jefferson’s presentation inscription to Lafayette in a gift copy of Notes on the State of Virginia (Paris, 1784-1785). (F230 .J4 1785; Gift of William Andrews Clark, Jr.)

While James sought his freedom another Virginian, Thomas Jefferson, was in Paris, where he arranged to print 200 copies of his book, Notes on the State of Virginia, during 1784-1785. These he privately distributed as he saw fit on both sides of the Atlantic. To a small number of specially bound presentation copies, including one sent to Lafayette, Jefferson added long, personal inscriptions. Lafayette’s copy now resides at U.Va., the gift of William Andrews Clark, Jr.

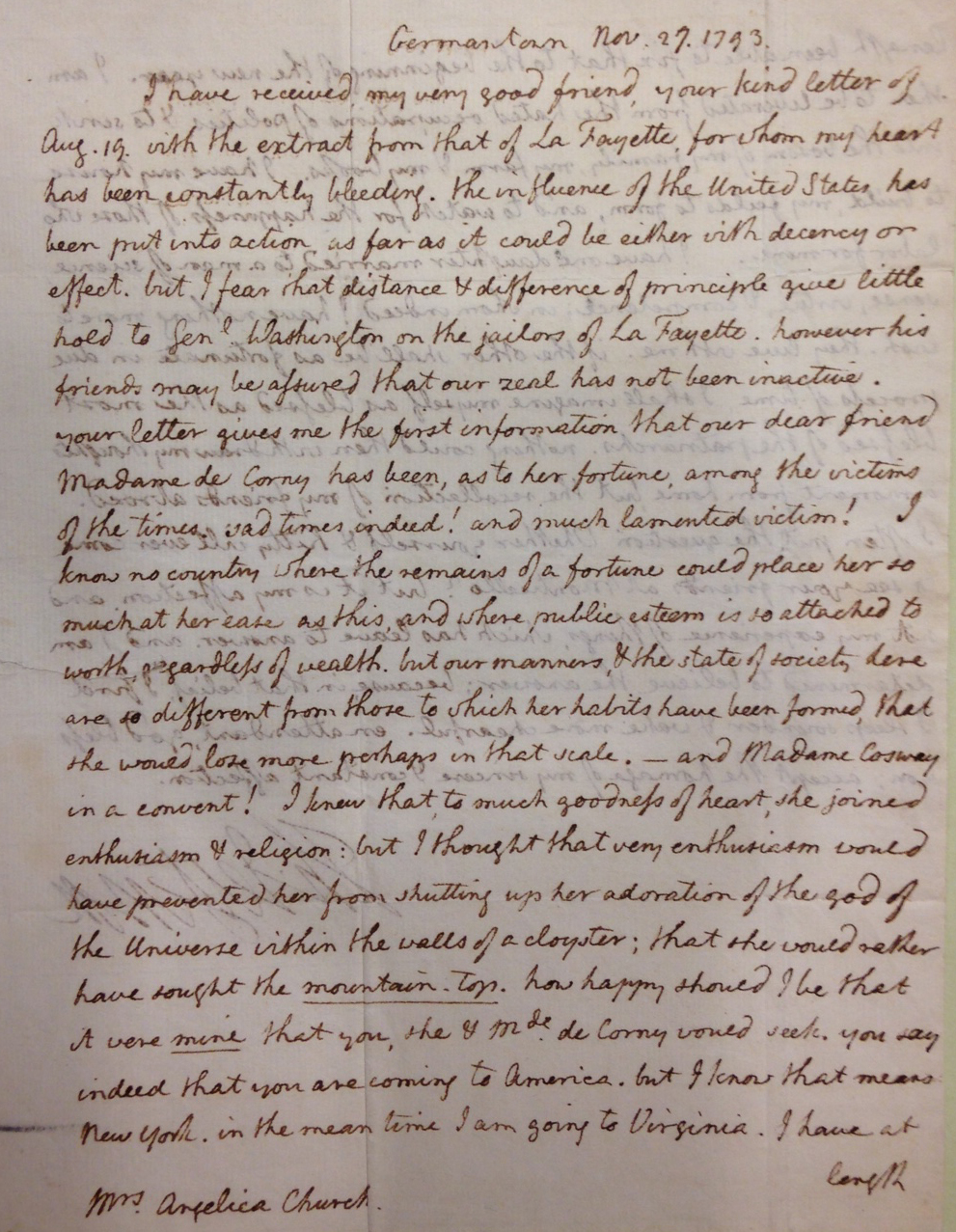

Thomas Jefferson’s letter of November 27, 1793 to Angelica Schuyler Church, in which he discusses American efforts to free Lafayette from a French prison. (MSS 11245-b)

Among the many friendships Jefferson cultivated in Paris was that of American expatriate Angelica Schuyler Church, wife of an American diplomat and Alexander Hamilton’s sister-in-law. Church later moved to London, where she monitored with increasing dismay the unfolding French Revolution and its tragic consequences for her friends. In her unceasing efforts to aid one imprisoned friend—the Marquis de Lafayette—Church was ultimately successful, as documented in an extraordinary cache of correspondence obtained by U.Va. a few years ago. Included is a 1793 letter from Jefferson, then Secretary of State, who thanks Church for forwarding a letter from “my very good friend” Lafayette, and informs her that “the influence of the United States has been put into action as far as it could be either with decency or effect.” (Sharp-eyed readers will also note a fascinating reference to Maria Cosway.)

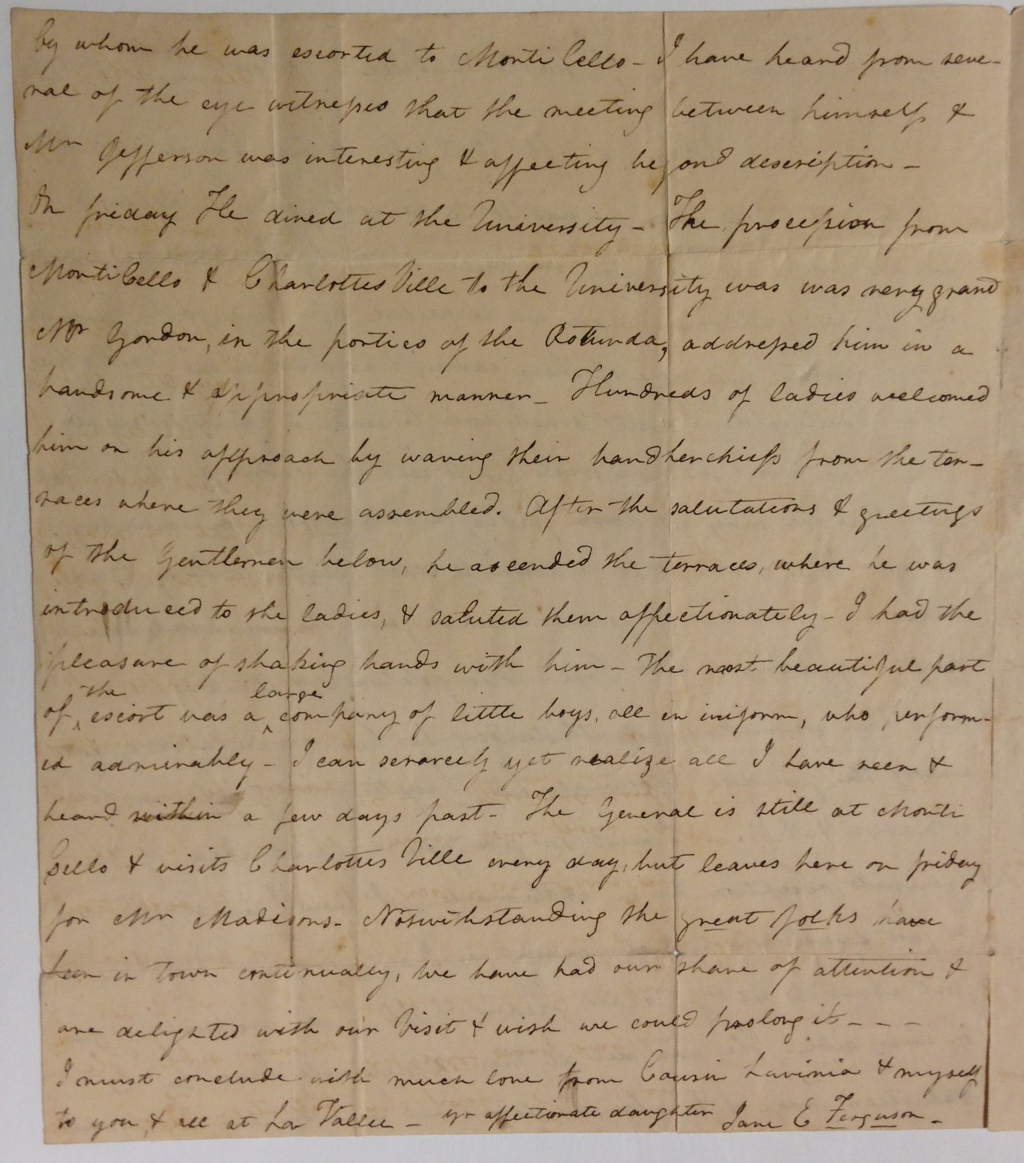

Most of our Lafayette holdings, however, relate to his extended American tour, from July 1824 to September 1825, during which he received the proverbial hero’s welcome from Americans in 24 states. In Special Collections one will find a diverse assortment of primary sources documenting Lafayette’s American travels, ranging from commemorative silk ribbons worn in his honor to eyewitness accounts of local festivities in letters sent to friends and family. From November 4-8, 1824, Lafayette was in Charlottesville where, after an emotional reunion with Jefferson at Monticello, Lafayette was fêted at a banquet held in the still-unfinished U.Va. Rotunda. Many interesting details of the event were conveyed in this letter from local resident Jane E. Ferguson to her father.

Jane E. Ferguson’s account of Lafayette’s reception at the U.Va. Rotunda on November 8, 1824. (MSS 38-122-a)

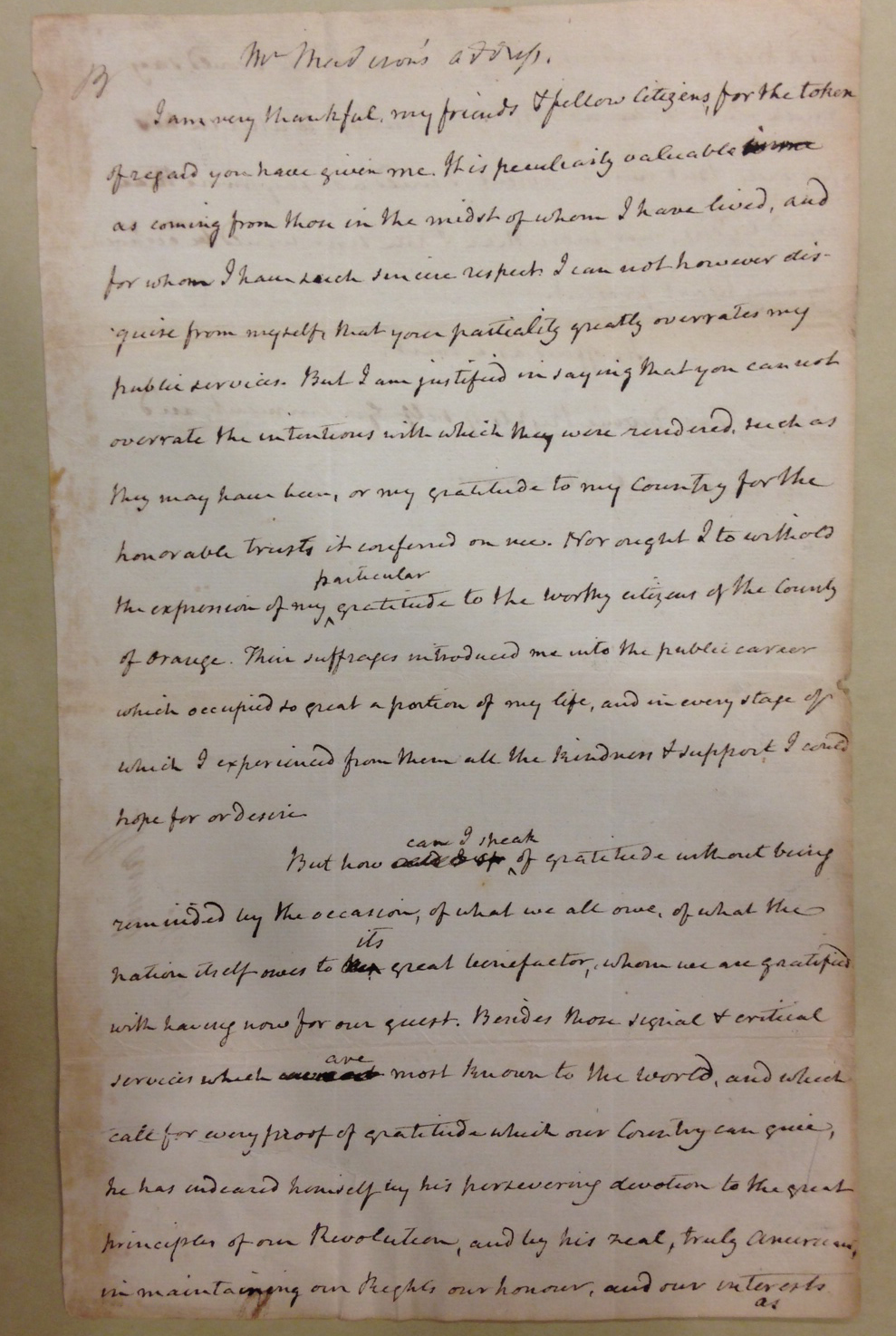

From Charlottesville Lafayette journeyed overland to Orange, Va., where on November 25, 1824, he was received with great ceremony. Making the public introduction was former president (and local resident) James Madison, whose remarks are preserved in the holograph draft to be found in the Small Special Collections Library.

James Madison’s remarks introducing Lafayette to the citizens of Orange, Va., November 25, 1824. (MSS 4677)

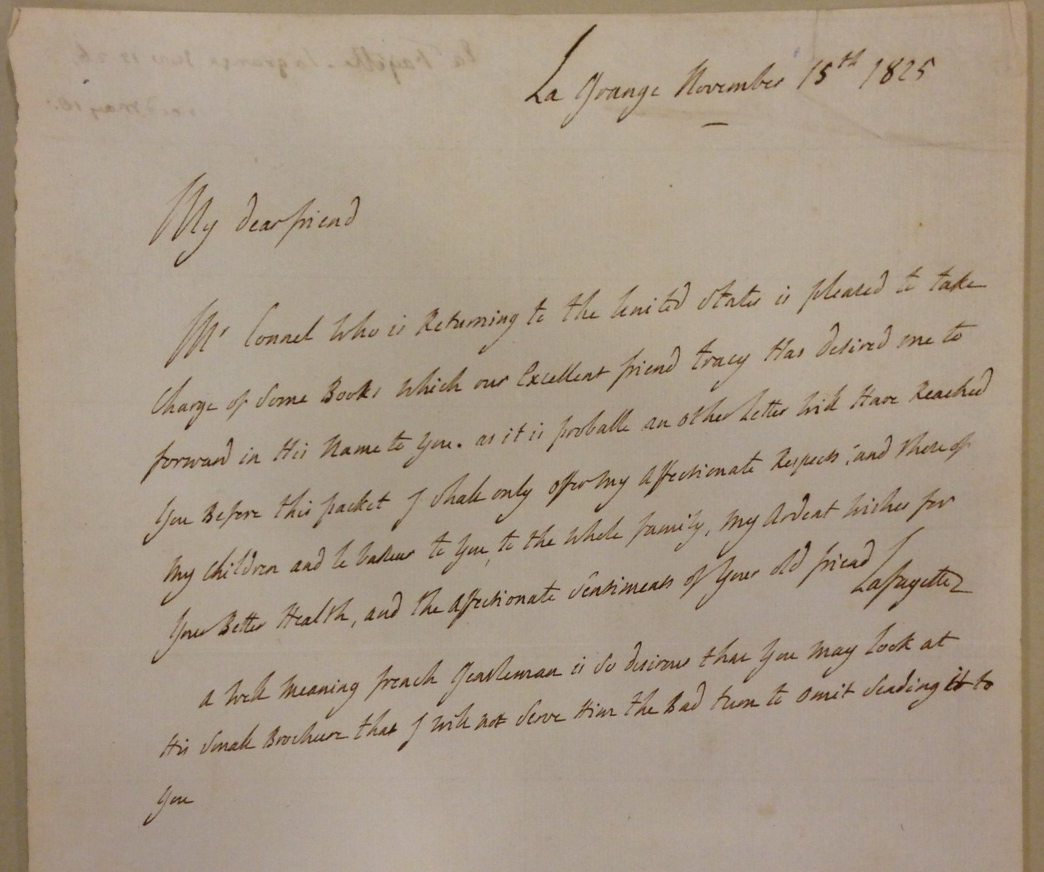

Nearly a year later Lafayette was back in France. On November 5, 1825, Lafayette wrote to Jefferson from his home in La Grange, advising him of a shipment of, what else but books, and sending “my ardent wishes for your better health, and the affectionate sentiments of your old friend.” On the reverse Jefferson noted the letter’s receipt at Monticello on May 18, 1826—perhaps the final communication he would receive from Lafayette.