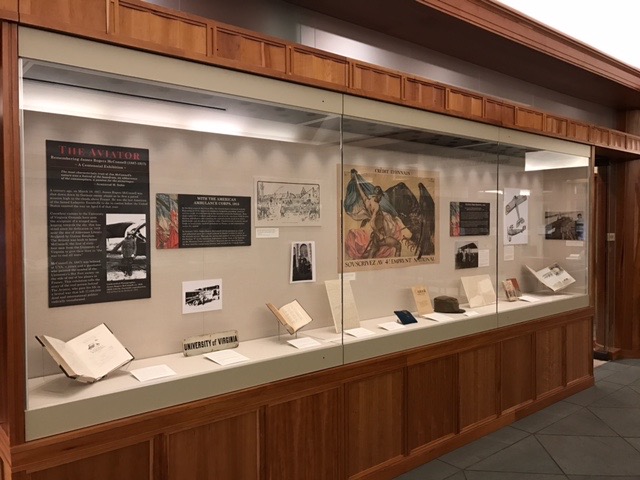

When students arrive at UVA, they learn about Thomas Jefferson, the Rotunda, and the academical village through the art and architecture on grounds. In between Alderman, Clemons, and the Special Collections libraries, there is a sculpture of a winged man, leaping into the sky, called “The Aviator.” In their rush to classes, students often pass by the statute without noticing. However, “The Aviator” is an important part of UVA’s history. It is a memorial to alumnus James Roger McConnell, who served in the American Ambulance Corps and the Lafayette Escadrille in France during the World War I. A new exhibition at Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library commemorates McConnell’s legacy and serves as tribute to his brief life. The exhibition tells the story of the real person behind “The Aviator”: the man who gave his life in a brutal war that left 17,000,000 dead and that radically transformed international politics.

A 1937 image of The Aviator, with the UVA Chapel in the distance on the right. The sculpture has been somewhere near its present site since it was first placed in 1919 (University of Virginia Visual History Collection).

McConnell matriculated at UVA in 1907. He spent two years in the College and one in the Law School, withdrawing at his father’s request in the spring of 1910 to enter business. While at Virginia, he led what appears to have been a dazzling social life. He was a member of Beta Theta Pi, Theta Nu Epsilon, O.W.L., T.I.L.K.A., the New York Club, and the German Club. He was King of the Hot Foot Society (precursor to the Imps); Editor-in-Chief of the yearbook, Corks and Curls; Assistant Cheer Leader; and founder of the Aero Club.

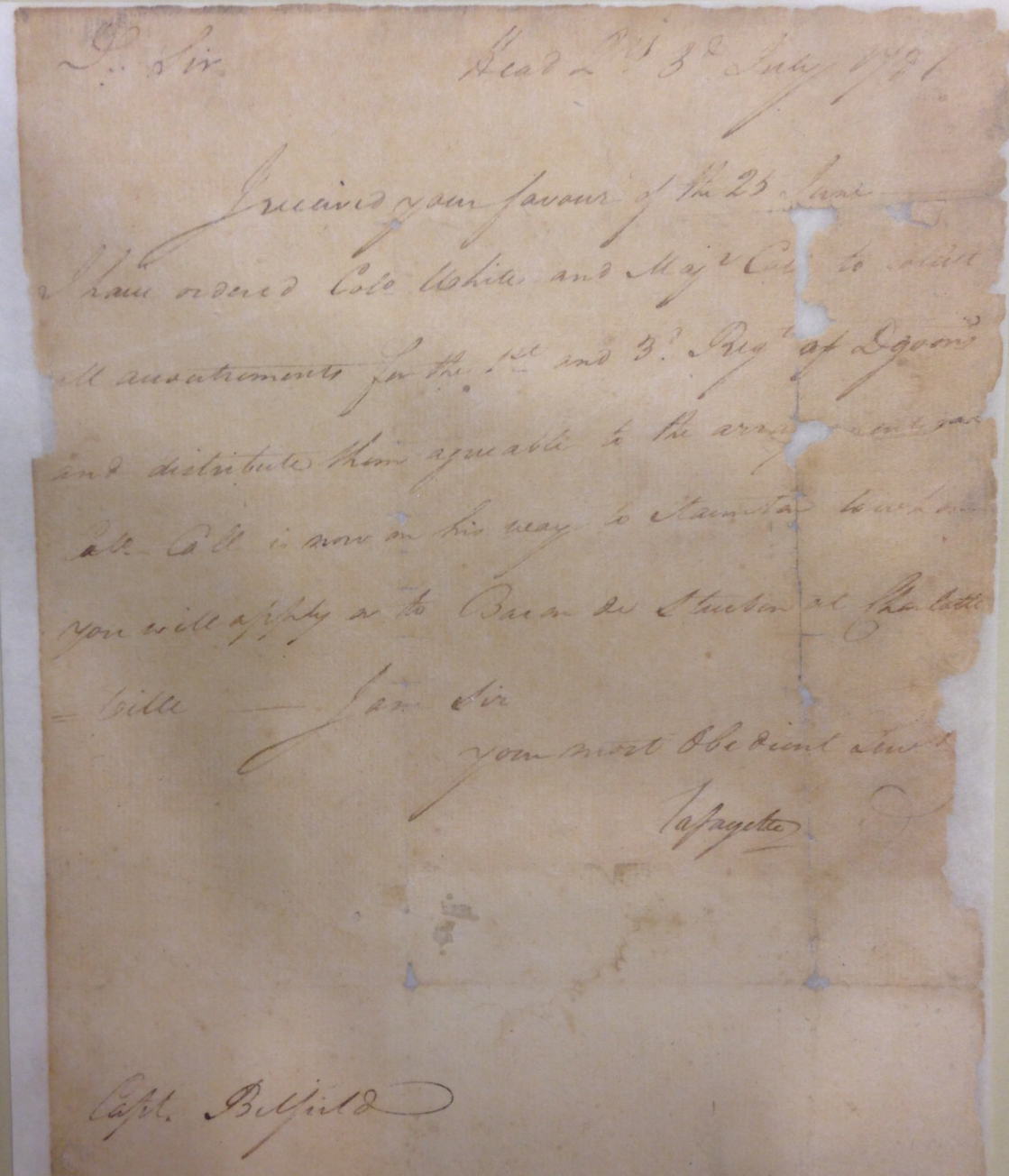

In 1915, McConnell left his position as a land and industrial agent for a small railroad in North Carolina to enlist in the French service. Through the spring and summer of that year he drove for Section “Y” of the American Ambulance, in the thick of the fighting on the Western Front around Pont-à-Mousson and the Bois-le-Prêtre. He was cited for conspicuous bravery and awarded the Croix de Guerre. He was one of many young men from UVA who served the French in the early years of the war.

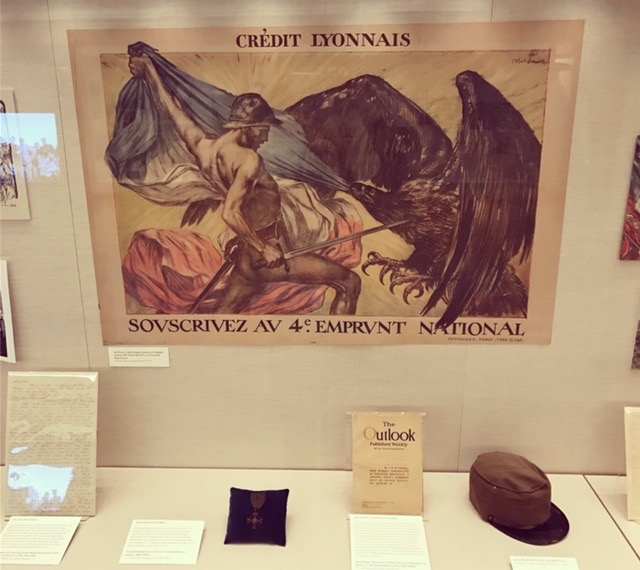

McConnell was given a Croix de Guerre for his bravery while driving ambulances on the Western Front. This particular Croix de Guerre was awarded to UVA alumnus George Brasfield, who also served in the Ambulance Corps (Section 516).

In 1916, McConnell left the Ambulance Corps to join the Lafayette Escadrille, a newly formed flying corps of Americans serving under French military command. He completed his flight training in February of that year and participated in the squadron’s first patrol in May. Later, he would take part in aerial actions during the great German offensive at Verdun in June and the Allied counteroffensives in July and August, with the symbol of UVA’s Hot Foot secret society on the side of one of his planes.

McConnell used his UVA education to urge the United States government to join the war. He published articles and letters about the Ambulance Corps, the Lafayette Escadrille, and the sacrifices of allied forces in The Outlook and The World’s Work. Later, his articles and letters were gathered into Flying for France, a book that joined the stream of popular war volumes appearing in American bookstores for readers of all ages. McConnell’s articles in The Outlook and Flying for France are some of the many treasures in the exhibition.

Shown here is a copy of The Outlook containing McConnell’s articles on the Ambulance Crops and the Lafayette Escadrille.

March 19, 2017 marked the one hundredth anniversary of McConnell’s death. On that day in 1917, McConnell was shot down by German enemy planes as he flew a patrol mission high in the clouds above France. He was last seen by a fellow pilot as they split up to battle German planes they encountered on patrol. When his plane was discovered, it had crashed at full throttle. Several bullets were found in his body, and it was likely he died before the plane hit the ground. His body had been stripped of identification and valuables by the time it was discovered by the French, but a piece of his airplane’s fabric fusilage was recovered, and appears in the exhibition. McConnell was the last American of the famed Lafayette Escadrille to die in combat before the United States entered the war on April 6 of that year.He was the first of sixty-four men from the University of Virginia to give their lives in World War I.

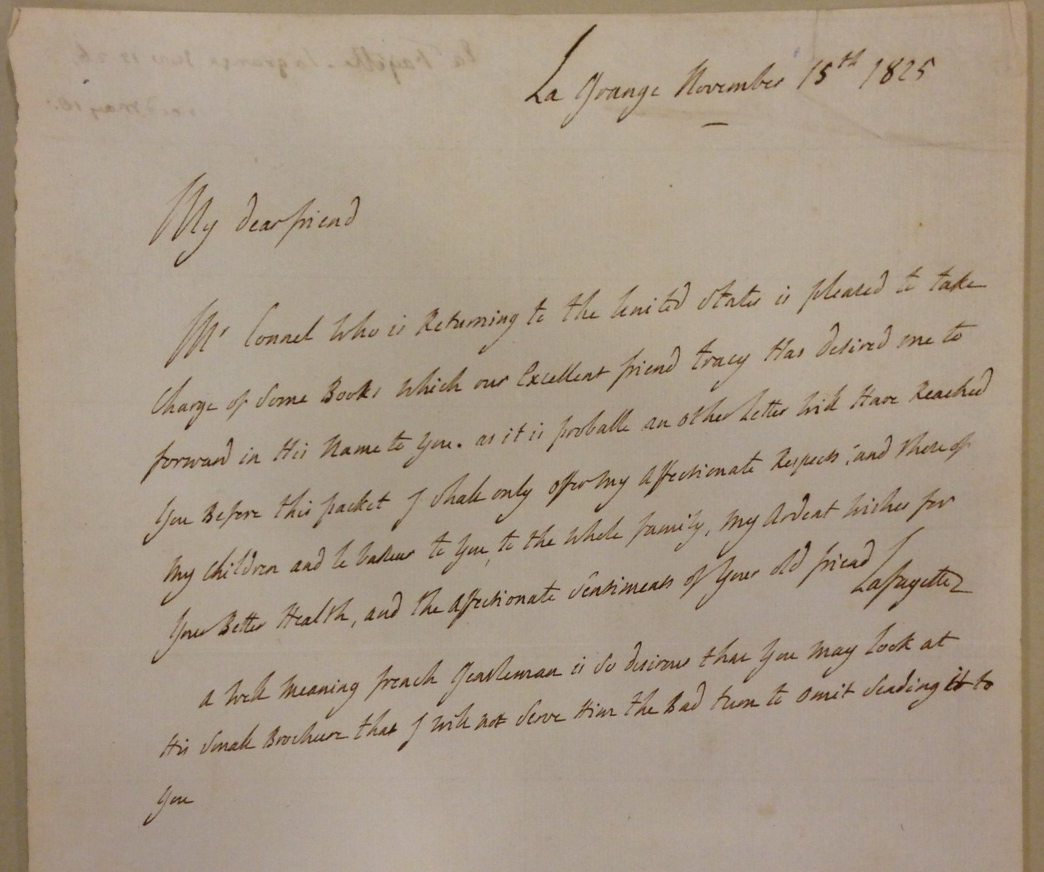

The exhibition features artifacts from McConnell’s time in the ambulance corps and the flying corps, as well as a section on monuments and memorials to his and UVA’s service to the French cause. The exhibition will be on view from until May 30th.