We are proud to announce the opening of our new First Floor exhibit, Troubadour, Vagabond, Visionary: The Journeys of Vachel Lindsay, curated by English graduate Student and Special Collections curatorial assistant Elizabeth Ott. Today on the blog, Elizabeth offers some reflections on the curatorial process in the following guest post. Thanks, Liz, and congratulations on your beautiful exhibition!

If there were a single collection in the Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections library that could represent all of the reasons special collections libraries exist, I think it would have to be the Vachel Lindsay Collection. Lindsay was an American poet of the early 20th century known for his tramping excursions of hundreds of miles across many states, when he traded poetry pamphlets and performances for food and lodging. He spent much of his life walking the lines between poet, painter, preacher, and philosopher. He’s exactly the kind of writer whose value to the history of literature is most easily lost in the ascetic pages of a Norton Anthology, where his booming vaudevillian voice, syncopated jazz rhythms, and elaborate tongue-in-cheek illustrations are reduced down to plain black ink on a white page.

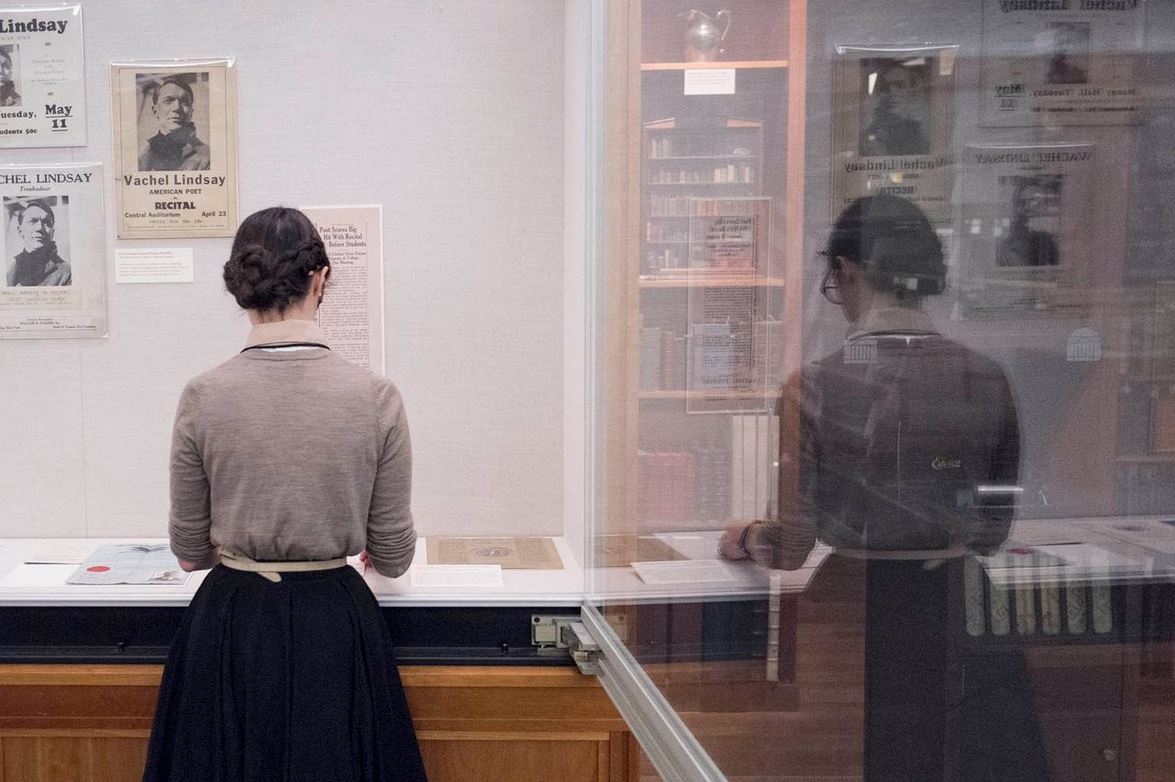

Exhibition curator Elizabeth Ott and her supervisor, curator Molly Schwartzburg, installing Lindsay’s Bibles in the exhibition. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak)

To understand Vachel Lindsay, you need to see all his stuff. To understand Vachel Lindsay, you need to visit Special Collections. This is because the manuscripts, printed books, and other materials in the stacks of the Small Library tell a vibrant story, one that casts Lindsay in a kaleidoscopic light of colors and shades, speaking of a rich artistic career. Enterprising, energetic, and prolific, Lindsay traveled America as a self-styled troubadour, distributed art and ideas with an earnest faith in the twin powers of Beauty and Art, and made a name for himself reclaiming poetry as the province of performance. The Vachel Lindsay Collection is wildly eclectic, encompassing everything from oil paintings and cherished slippers to folksy illustrated pamphlets and the blocks used to print them.

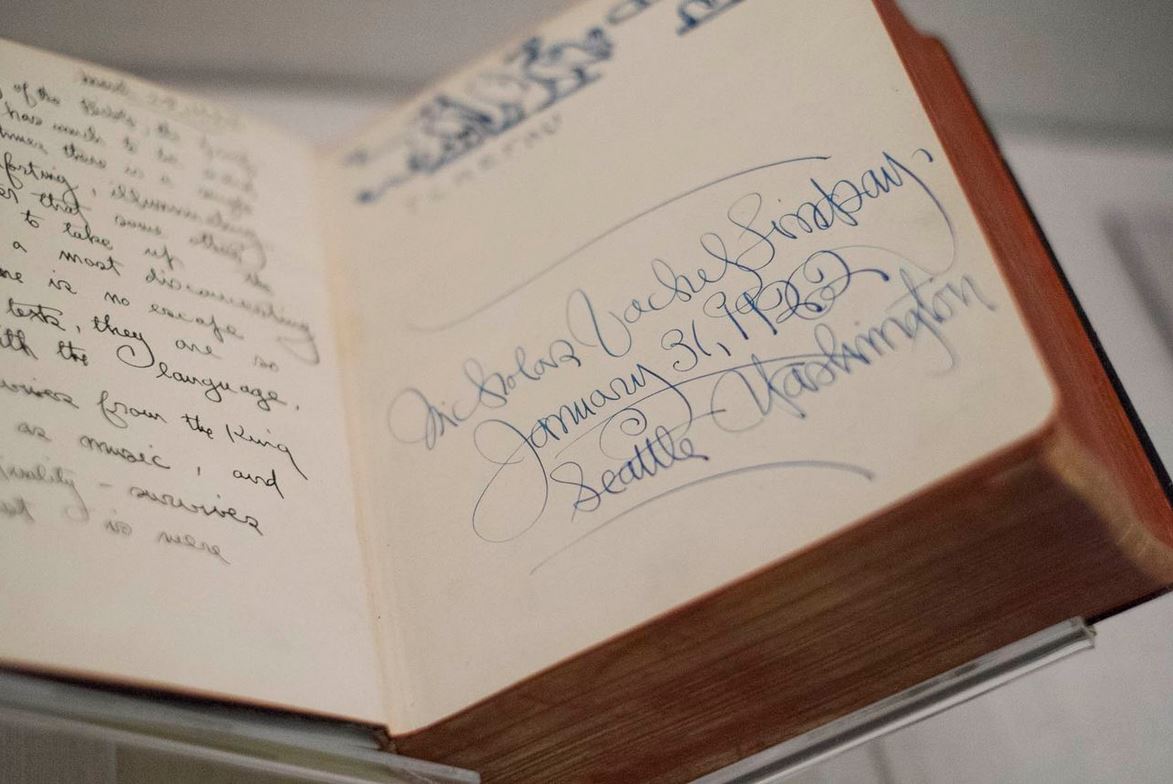

One of Vachel Lindsay’s Bibles, inscribed with his elegant script, ready to be installed in the exhibition. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak)

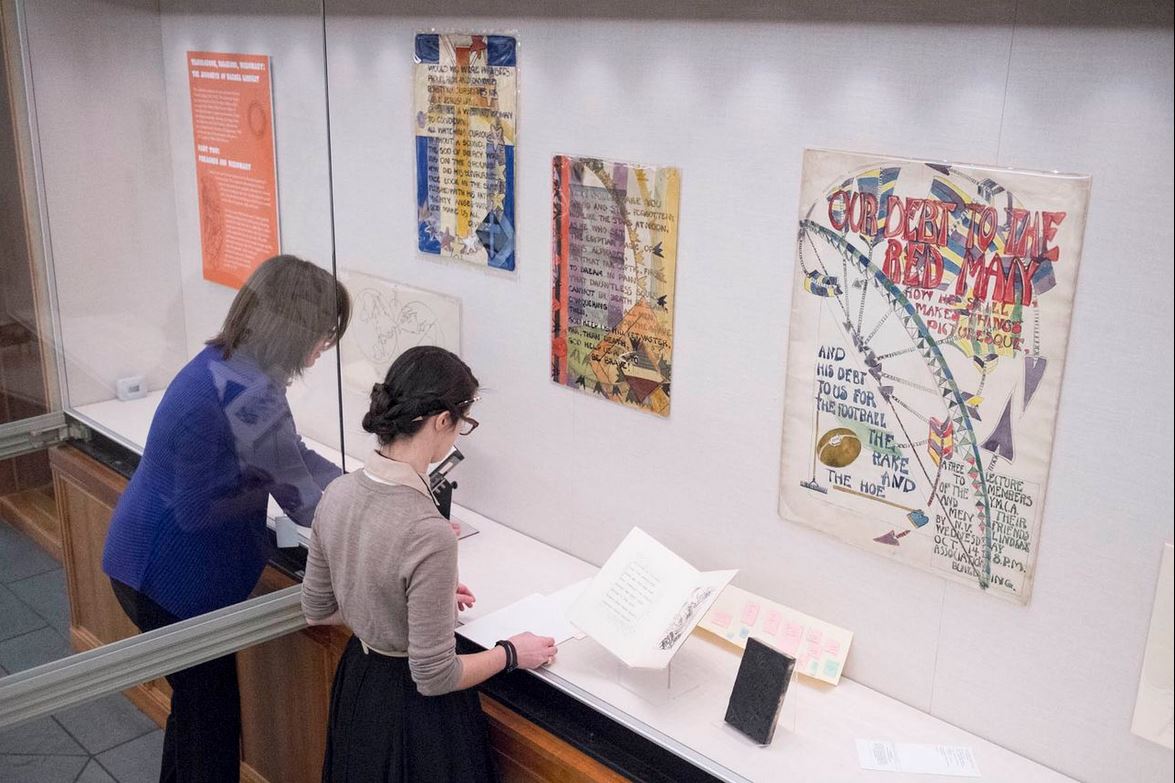

Because of Lindsay’s broad interests and the great scope of the collection, deciding what aspect of Lindsay’s career to exhibit was no small task. I wanted to showcase the range of his work while at the same time giving a sense of just how much he dovetailed with the intellectual and artistic concerns of his day. To me, Lindsay seemed so much a part of the American landscape—an America still in the process of building an identity. Lindsay, like many American poets, looked back to create something unique and new, breaking from tradition by invoking an almost transcendental link to a mythic and stylized past.

The decision to focus the exhibition on Lindsay’s journeys, both literal and figurative, grew out of two maps that now hang in the first case of the exhibition. Both maps are fairly ordinary, save that Lindsay has embellished both, labeling them with paint and pen. The first records his tramping journeys between 1904 and 1916. The second divides the country into regions of Lindsay’s devising, with his characteristic penchant for the symbolic over the literal. I wanted to tell the story of these two maps, of Lindsay’s actual treks across the United States, but also of his visions of the journey America, as a country, was to undertake.

The resulting exhibition thus tells two stories. The first is the story of what Vachel Lindsay means to America—how his tramping journeys presaged the hobo culture of the 1920s and 30s and influenced generations of poets who drew inspiration from folk culture. The second is the story of what America meant to Vachel Lindsay, his mythopoeic universe with Springfield, Illinois (his hometown) at the center. Though this exhibition barely scratches the surface of his fascinating life and work, it samples a great range of the materials that survive in the Vachel Lindsay Collection, testifying to the life and works of this now obscure but enduringly influential American poet.