This is the second in a series of three posts, spotlighting the mini-exhibitions of students from USEM 1580: Researching History, Fall 2015.

***

Carolyn Ours, Second-Year Student

“He has made everything beautiful in its time”: Biblical Art and Typography Through the Ages”

This collection of Bibles and Bible fragments spans the time frame from the 12th century to the 21st in an attempt to examine the evolution in graphical and typographical interpretations of the world’s bestselling book. While ample commercial copies are available for sale, this fact has not led to the complete disappearance of rare and artistic interpretations that are consistent with the painstaking early editions of the text. Certain elements persist throughout time, specifically colored rubric text and initial letters. Additionally, most Bibles remain printed in two columns to conserve space and make the layout more conducive to the printing of poetry.

Images can have a profound effect on one’s understanding of the Bible by enabling the reader to create concrete mental images and aiding in the conceptualization of abstract concepts. On the other hand, the absence of images allows the reader to formulate their own understanding in accordance with their worldview. Evolving technology has allowed artists to promote understanding of the text in an ever-changing media landscape.

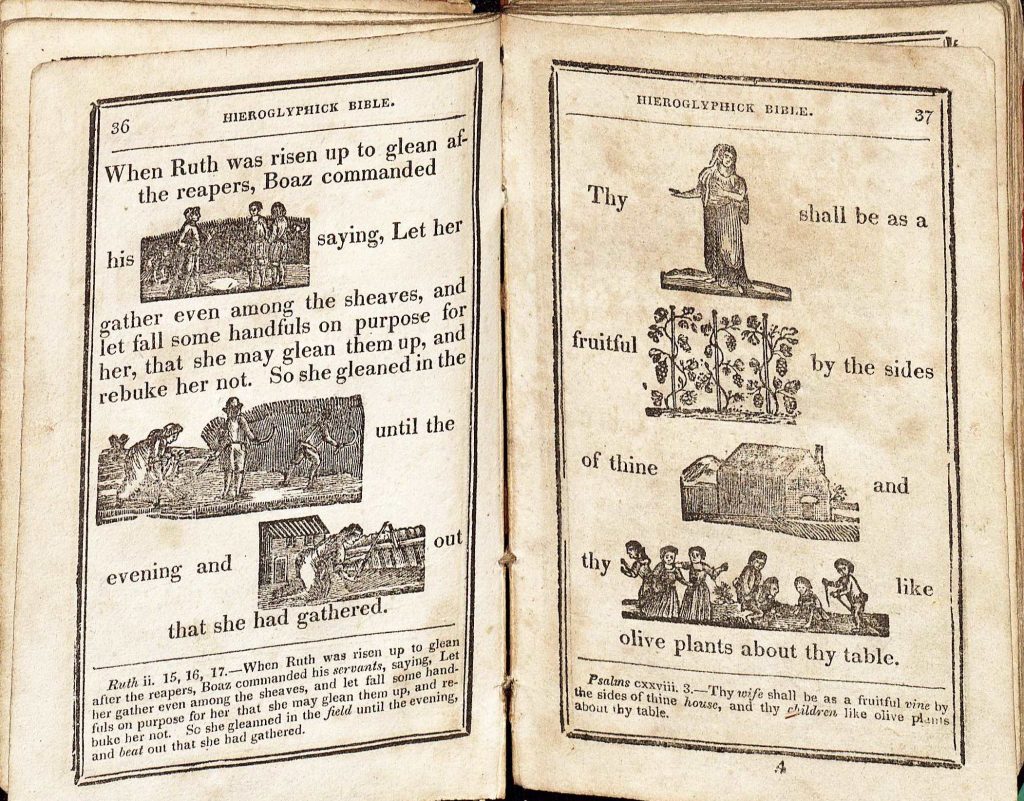

“The Hieroglyphick Bible: or Select passages in the Old and New Testaments, represented with emblematical figures, for the amusement of youth: designed chiefly to familiarize tender age, in a pleasing and diverting manner with early ideas of the Holy Scriptures. To which are subjoined, a short account of the lives of the evangelists, and other pieces.” 4th Ed. Hartford: Silas Andrus, 1825. (BS560 .A3 1825). Gift of Mrs. René Müller

In his “Hieroglyphick Bible,” published in 1825, Silas Andrus introduces the nation’s youth to both reading and Scripture by replacing words with detailed images—a technique called rebus. The almost five hundred representations were carved by hand, and display a range of topics ranging from the abstract (God, prosperity, and death) to the concrete (men, children, and the Crucifix). Earlier copies originated in England before the popular style made its way to the United States. Andrus’ work contains selections from both Testaments, with decorative border work and footnote-style text indicating the meaning of each image in context. (Image by Penny White)

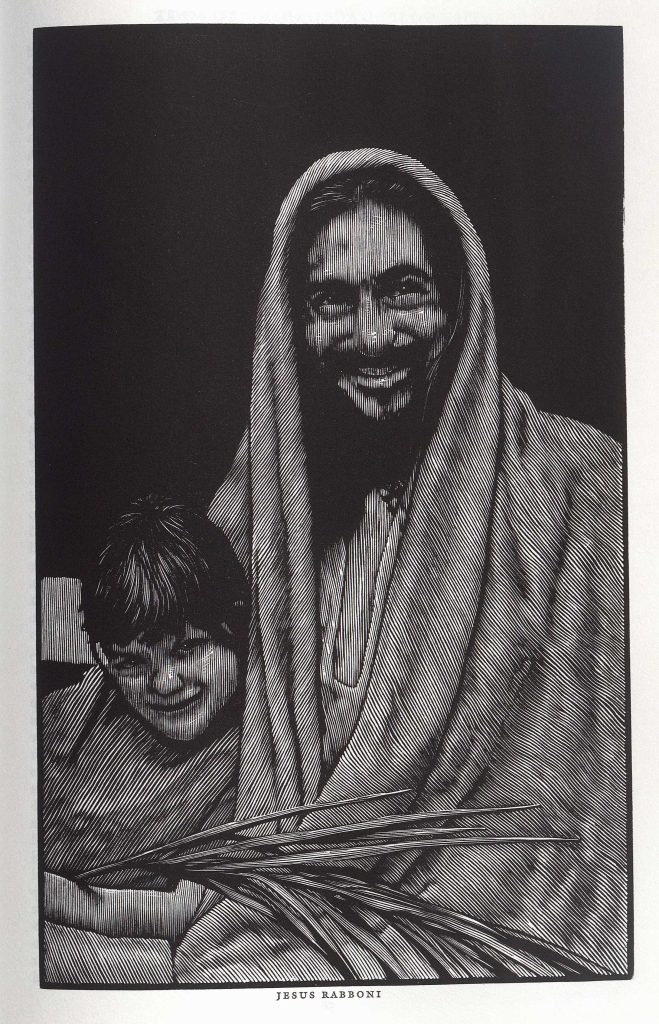

“Jesus Rabboni” from “The Holy Bible: containing all the books of the Old and New Testaments.” North Hatfield, Mass: Pennyroyal Caxton Press, 1999. (BS185 1999 .N67)

The Pennyroyal Caxton Bible, published in 1999, is the first fully illustrated Bible in almost a century. Artist Barry Moser worked full time over the course of three-and-a-half years to hand carve the 233 incredibly lifelike and distinct images, working mostly from live models and creating an everyman visualization of the text, particularly unnerving in its realistic depiction of malicious figures, including Satan. His inspiration for Jesus, a chef at a local restaurant, is a significant variation from previous hyper-Anglicized depictions of Christ. The book maintains long-standing traditions in printing red rubrics of the words “God”, “Christ”, and “Amen” at the beginning and end of each Testament. The Bible maintains the two column tradition, fitting images and text into a consistent space throughout both volumes. (Image by Penny White)

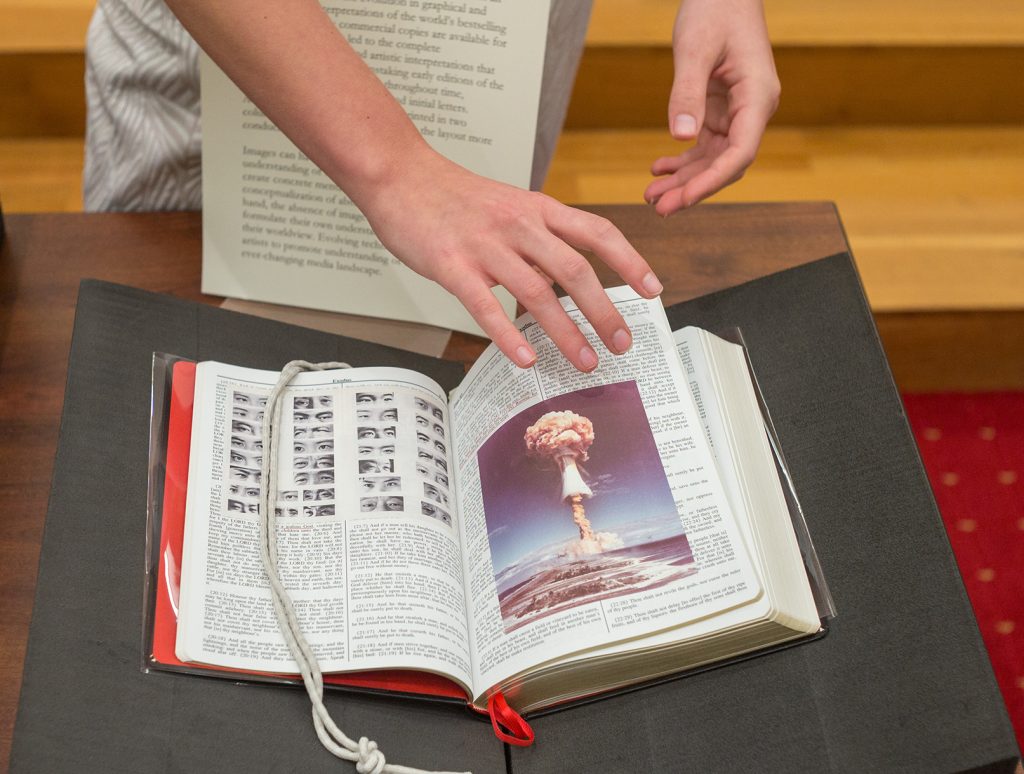

“Holy Bible.” London: MACK: AMC, 2013. (N7433.4 .B77 H65 2013)

Purchased from the Agelasto Family Library Fund, 2013/2014

While its outer appearance is no more remarkable than a Bible from a hotel nightstand, Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin’s Holy Bible pushes the envelope in graphical interpretations of the sacred text. Influenced by the Philosophy conveyed in Israeli scholar Adi Ophir’s “Divine Violence”, the pair selected images from the London Archive of Modern Conflict to impose over the standard printed text. They use red underlining to highlight specific phrases that correlate to the images, forgoing captions and instead permitting the reader to draw their own conclusions. Images of war, destruction, hatred, sexuality, nature, and death juxtapose the sanctity of the book with its frequently violent and destructive themes, emphasizing Ophir’s argument that God is manifested in the modern world through government and catastrophe. (Photograph by Sanjay Suchak)

***

Tallulah Tepper, First-Year Student

The Architecture of Monticello

Thomas Jefferson’s estate, Monticello, is a historical site with much architectural significance. Known widely as one of Jefferson’s greatest accomplishments, Monticello, completed in the early 1800s takes inspiration from European buildings. Additionally, Jefferson’s architecture inspired other buildings across the nation, and similar architecture can be found at the University of Virginia.

Monticello and Jefferson go hand in hand. As Thomas Jefferson once said, “architecture is my delight!” The estate allows one to truly understand Jefferson, his attention to excellence and detail, and his love of culture and worldliness.

Overall, this exhibit allows insight into how Jefferson thought, planned, and designed, and proves where ideas from Monticello came from and how and why Monticello is still so significant today.

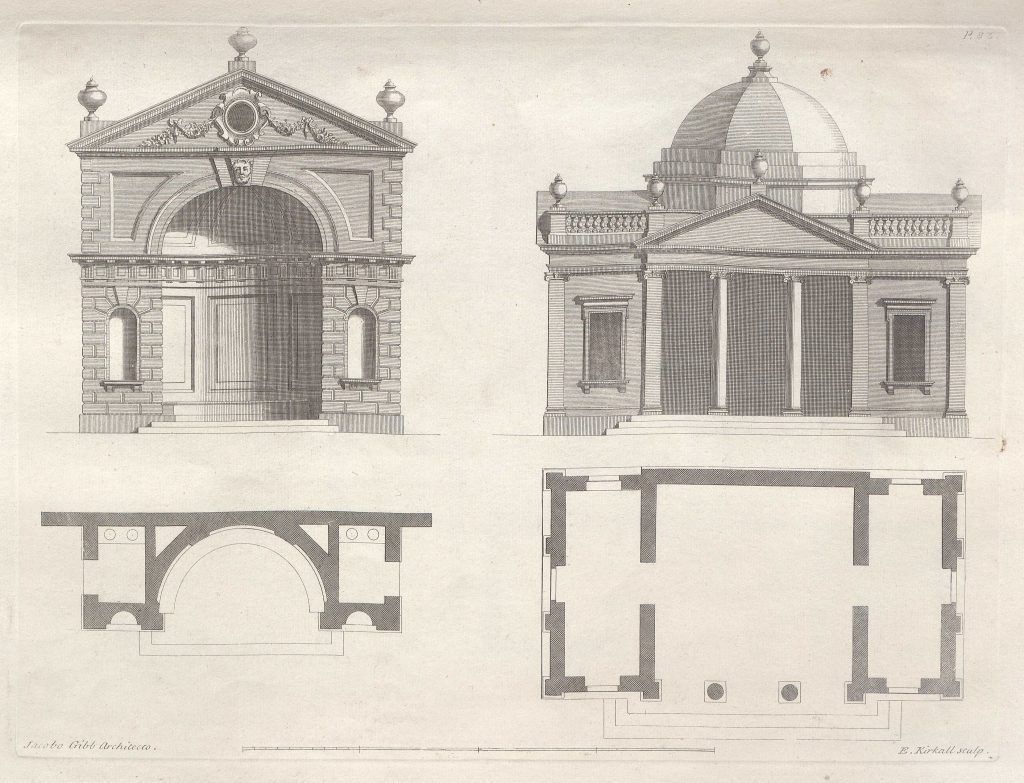

Gibbs, James. “A Book of Architecture: Containing Designs of Buildings and Ornaments.” London: S.n., 1728. (NA2620.G5 1728). Acquired from Architecture laboratory fee fund.

Thomas Jefferson had inspiration from multiple European influences, James Gibbs being one of them. In this house-plan, one can draw clear correlations between the architecture of Monticello and Gibbs’ drawing. Perhaps the lesser known inspiration of Jefferson, Gibbs drew plans for houses and churches alike. Pictured here is a house upon an estate. Jefferson was a great fan of European architecture, traveling throughout Europe, especially France and London, finding ideas for his Monticello. (Image by Penny White)

Jefferson, Thomas. Early Sketch Of Monticello. 1769. MSS 5385-ae). Thomas Jefferson Foundation

This sketch of Monticello was drawn by Thomas Jefferson himself circa 1769, before the actual creation of the Estate. This was Jefferson’s first sketch, and while it does clearly resemble Monticello today, the building was designed and redesigned multiple times before its completion in the early 1800s. Mr. Jefferson’s attention to detail even in an early sketch and clear vision with European influences provides insight into what Jefferson was aspiring toward as Monticello was constructed. (Photograph by Sanjay Suchak)

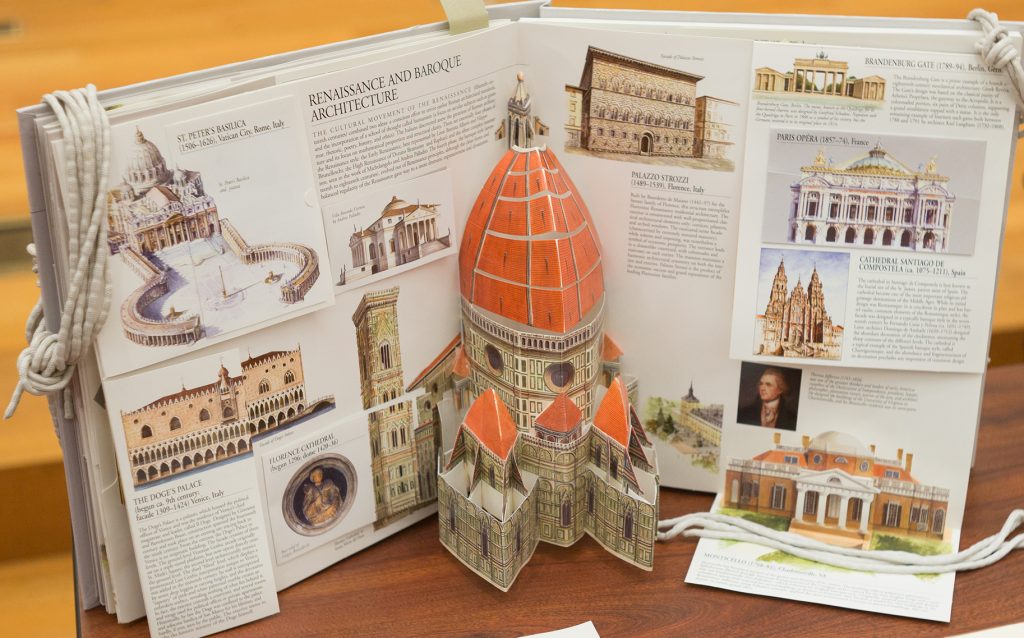

Radevsky, Anton, and Pavel Popov. “Architecture Pop-up Book.” New York, NY: Universe, 2004. (NA202 .R24 2004). Minor Fund, 2004/2005.

This pop up book contains many three dimensional replicas of famous architectural sites. On the page shown, a pop up Palladio and a pop up Monticello are included. Setting the three dimensional models next to each other, although small in scale, one can see the similarities between the two. It is clear that Jefferson’s Monticello took inspiration from Palladio, and the model also provides insight into the differences between the two. Overall, this small but accurate 3-D model allows one to experience Monticello as more than just a picture. That which does not appear simply on the page quite literally jumps off of it to show a more detailed artistic description of the building, dimensions, and shape of Monticello. (Photograph by Sanjay Suchak)