This week, we are pleased to feature a guest post by Gayle Jessup White, who is a Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies Fellow for 2014. Ms. White researched the collections of Thomas Jefferson, the Edgehill Randolph family, and the Nicholas family while at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

It was jarring to read. “Dear Sir:” began the 1814 letter from P. Randolph (possibly Peyton Randolph, son of U.S. Attorney General Edmund Randolph, acting Virginia governor from 1811–1812, and cousin of Thomas Jefferson) written to Wilson Cary Nicholas, 19th governor of Virginia and Jefferson in-law:

“I beg leave to enquire of you what disposition you intend to make of William? If you do not wish to keep him, I am anxious to have him sold, in order to meet the note … which will shortly become due…I would thank you to employ some one to sell him immediately… Be so good as to let me hear from you on that subject.”

The polite exchange between the two white southern patricians left me feeling sick as I read about William, the enslaved man whose life meant little more to them than settling a financial obligation. I bristled while contemplating that both white men, public servants of a fledgling democracy, founded on the proclamation that “all men are created equal,” held in the balance a black man’s future, a man who would probably die a slave, as would his children, and grandchildren. My twenty-first-century mind couldn’t wrap itself around his nineteenth-century condition. Yet, I held in my hand this letter, a letter that’s part of the University of Virginia Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library’s rich archive about Jeffersonian history.

I spent long happy days at the Small Special Collections, poring over letters, official documents, old photos, even examining locks of Thomas Jefferson’s hair, in search of my own family’s ties to Jefferson and his extended family. Oral history, fragmented documentation, and DNA testing indicate that my African American family is directly descended from Thomas Jefferson and his wife Martha. Research points to my great-grandmother Rachael Robinson having several children with Jefferson’s great-great-grandson Moncure Robinson Taylor shortly after the Civil War. It’s a relationship that seems to have begun when the couple was young and appears to have lasted decades. Perhaps they bonded during and after the harrowing years of the war. Whatever the case, I have come to believe theirs was a love relationship, one that brought me to U.Va. to learn more about them and the times in which they lived.

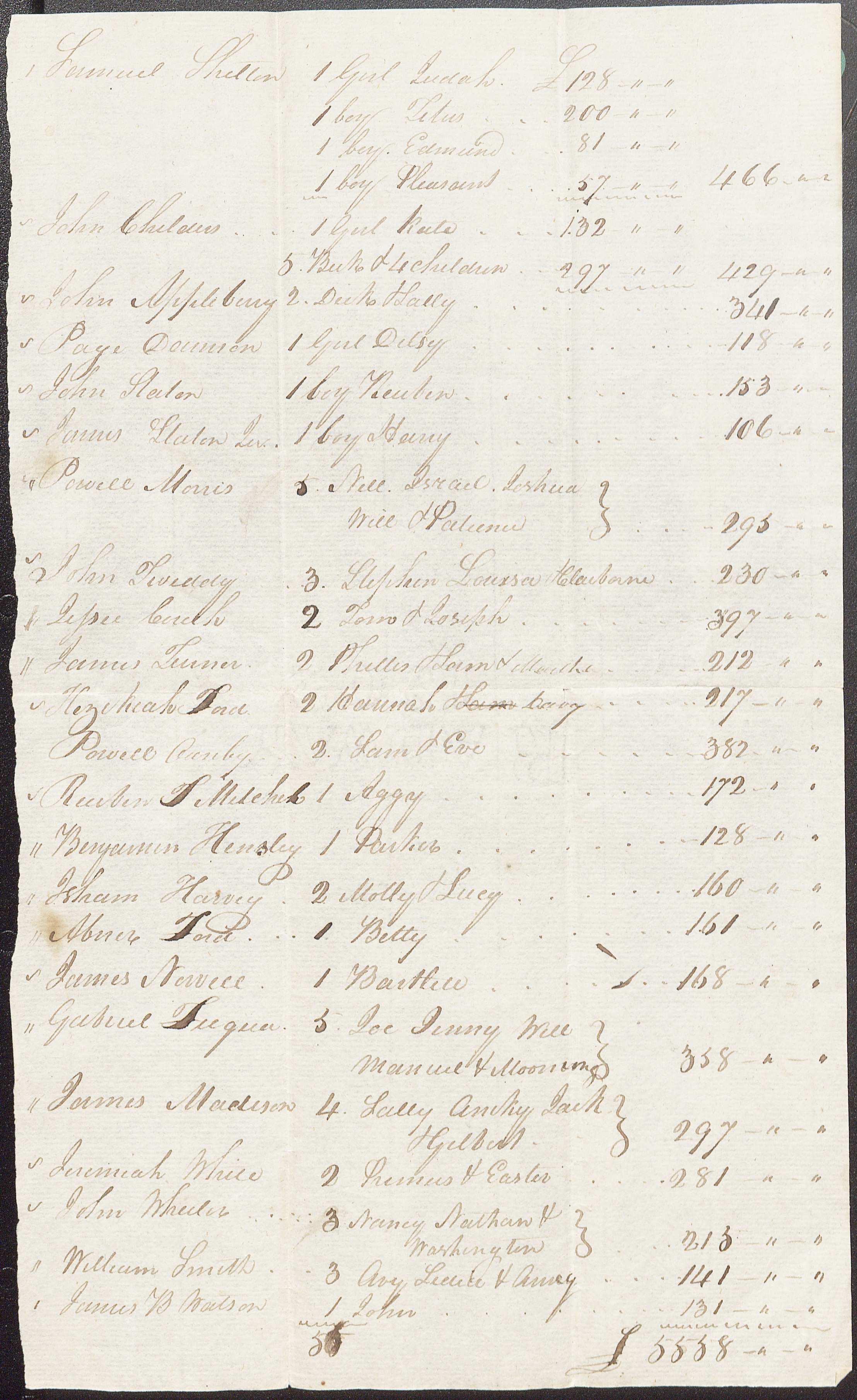

An Account of Slaves, n.d. (MSS 5533. Papers of the Randolph Family of Edgehill and Wilson Cary Nicholas. Gift of Misses Margaret and Olivia Taylor and Mrs. Mary Mann Moyer. Image by Petrina Jackson)

What I found was a record of lives interrupted and altered by disease, early deaths, war, and chattel slavery. And while I felt resentment and bitterness toward the people who owned William and others who wrote dismissively of their enslaved people, I also found myself captivated by and at times sympathetic to the tragedy of their lives. For example, Jane Hollins Nicholas Randolph, wife of Thomas Jefferson’s grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph and my great-great-great-grandmother, lost five of her 13 children.

Portrait of Jane Hollins Nicholas Randolph, n.d. (MSS 5533-c. Additional Papers of the Randolph Family of Edgehill on deposit from Steven M. Moyer. Image by Petrina Jackson)

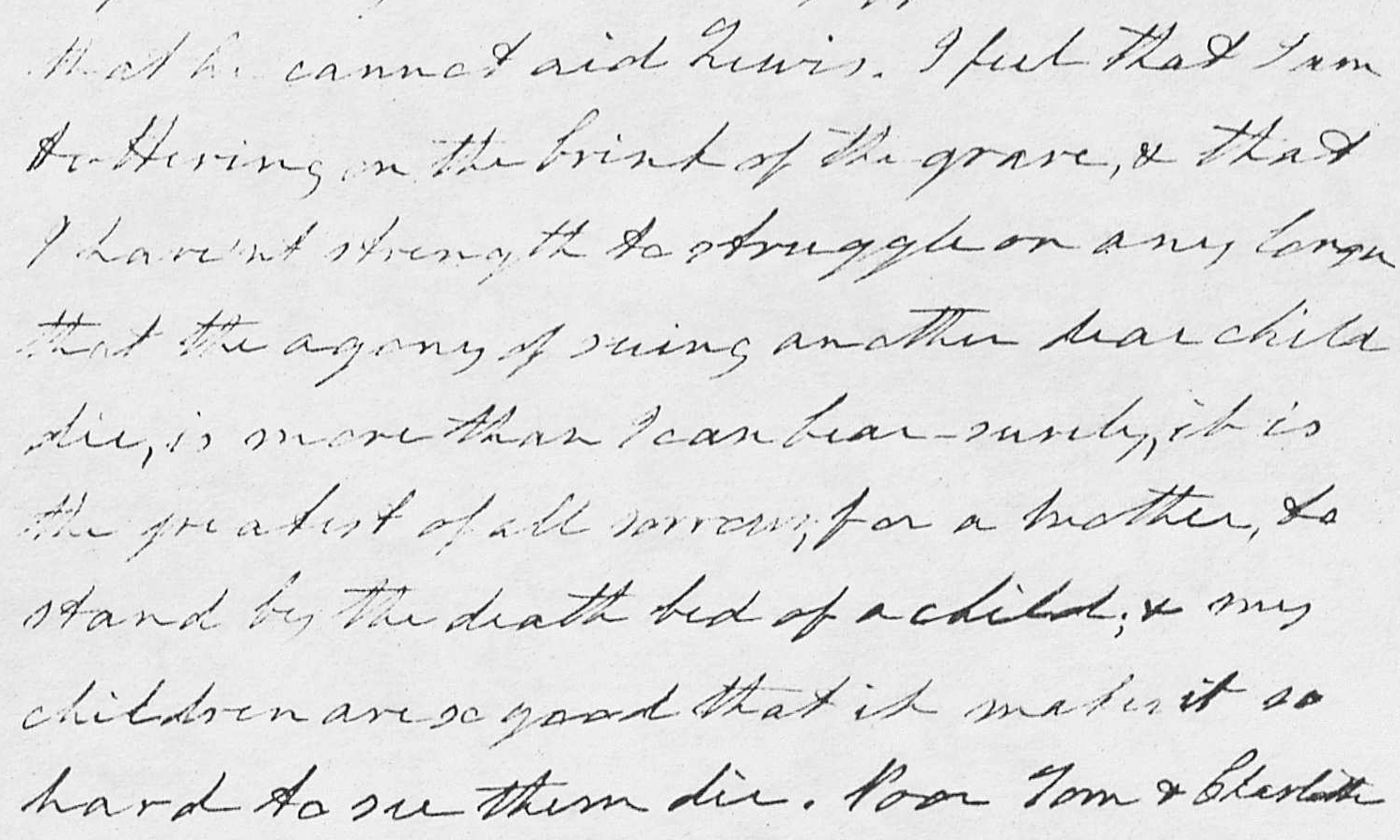

The Civil War shattered her life–she and her family were, after all, on the wrong side of history. Still, I couldn’t help but feel sympathy for her as I read the words of this November 15, 1870 letter from her to her cousin Mary:

“You have probably heard from others, dearest Mary of Lewis, I fear almost desperate state of health, caused by taking cold last December which he never got rid of which has brought him to a most alarming state…

I feel that I am teetering on the brink of the grave, & that I haven’t strength to struggle on any longer that the agony of seeing another dear child die is more than I can bear – it is the greatest of all sorrows for a mother… to stand by the death bed of a child & my children are so good that it makes it so hard to see them die.”

Detail of copy of letter from Jane Hollins Nicholas Randolph to her cousin Mary, 15 November 1870. (MSS 9828-a. Additional Papers of the Randolph-Nicholas Family. Image by Petrina Jackson)

Jane Randolph died two months later, struck down by the news that her youngest child Lewis, the one whose life-threatening illness had her “teetering” at the grave, would soon succumb to “consumption.” How could I not feel for her–I, too, am a mother.

Yet this woman, my ancestor, owned slaves, some of whom may have been my ancestors as well. Jane’s former enslaved people were said to have wept at her gravesite. I too wept as I read her plaintive letter, one of many she had written and that are housed at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. For me, Jane’s letters gave her a humanity that history had stolen. Poor William and other enslaved people will never have theirs restored.