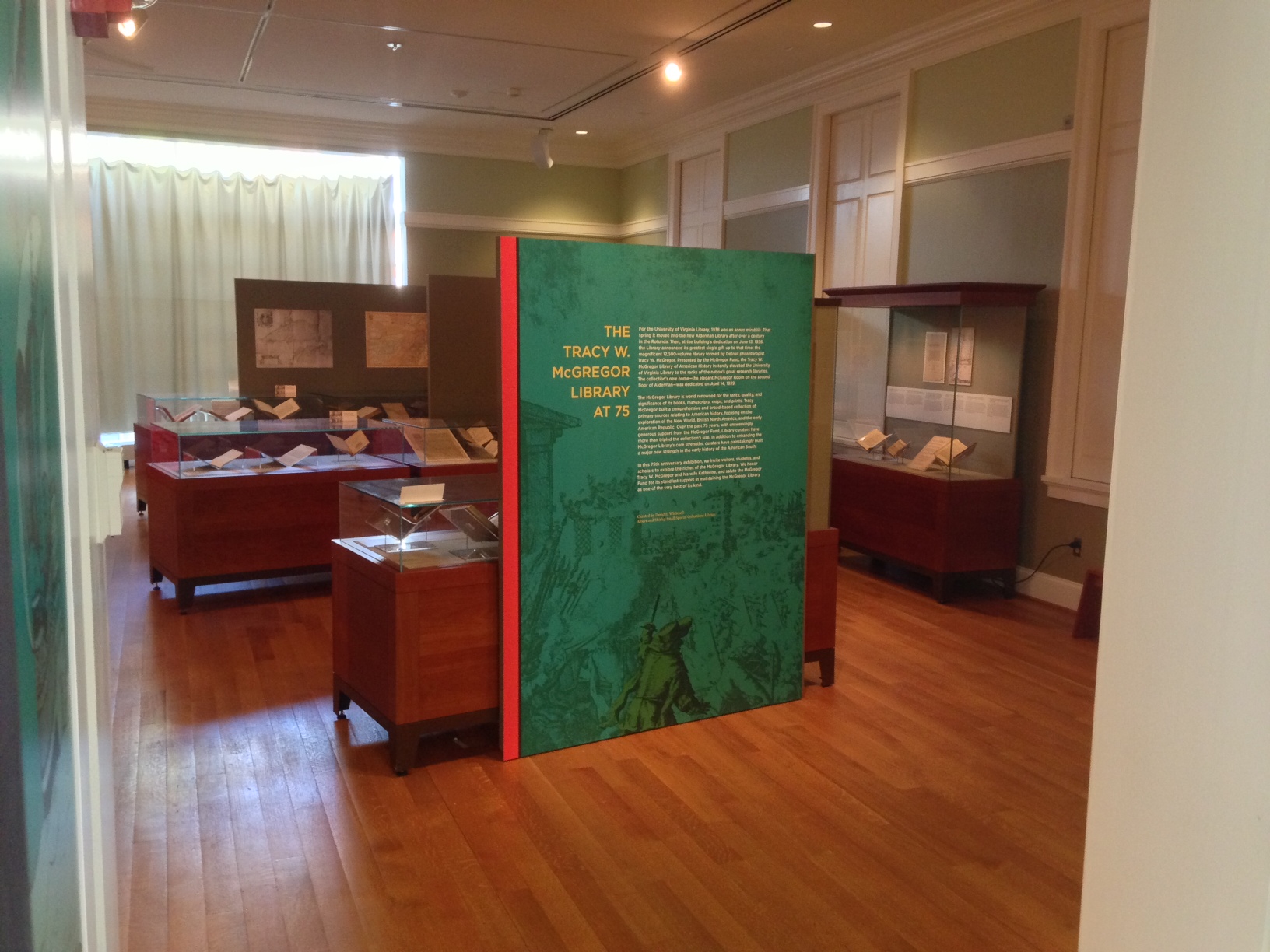

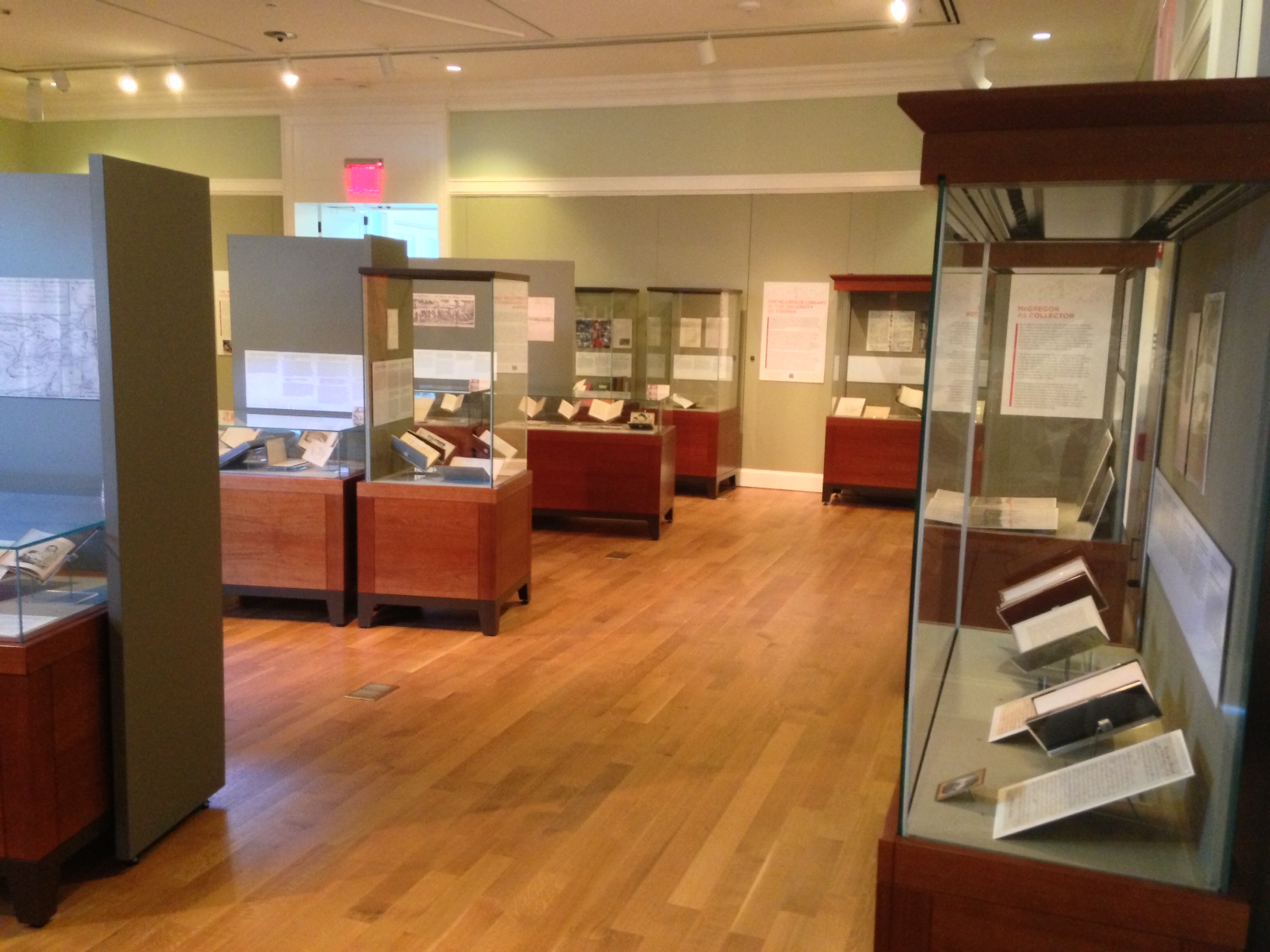

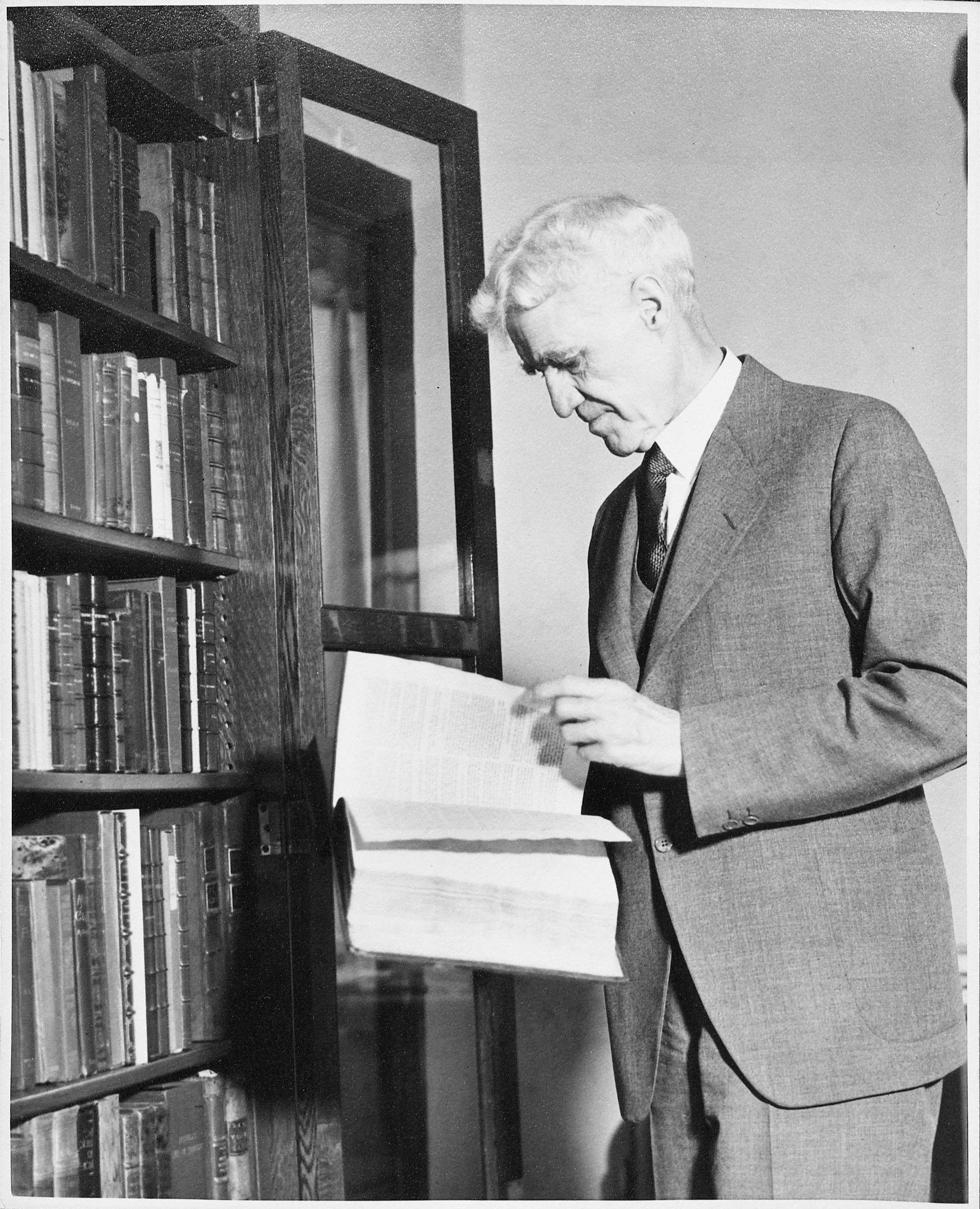

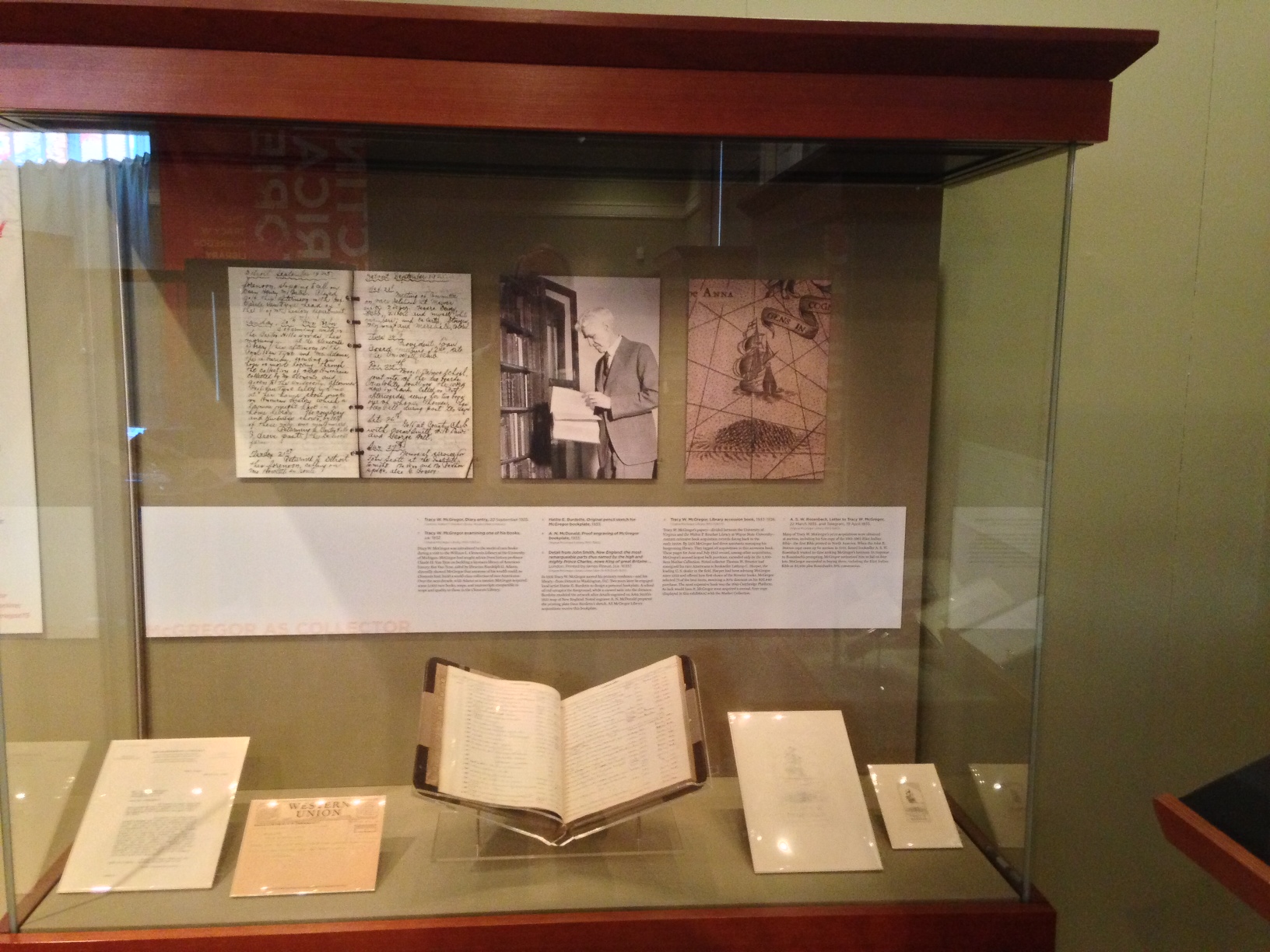

The opening last week of Collecting American Histories: the Tracy W. McGregor Library at 75—the major new exhibition of highlights from our world renowned McGregor Library of American History—prompts us to describe a few of the many acquisitions made for the McGregor Library in recent months.

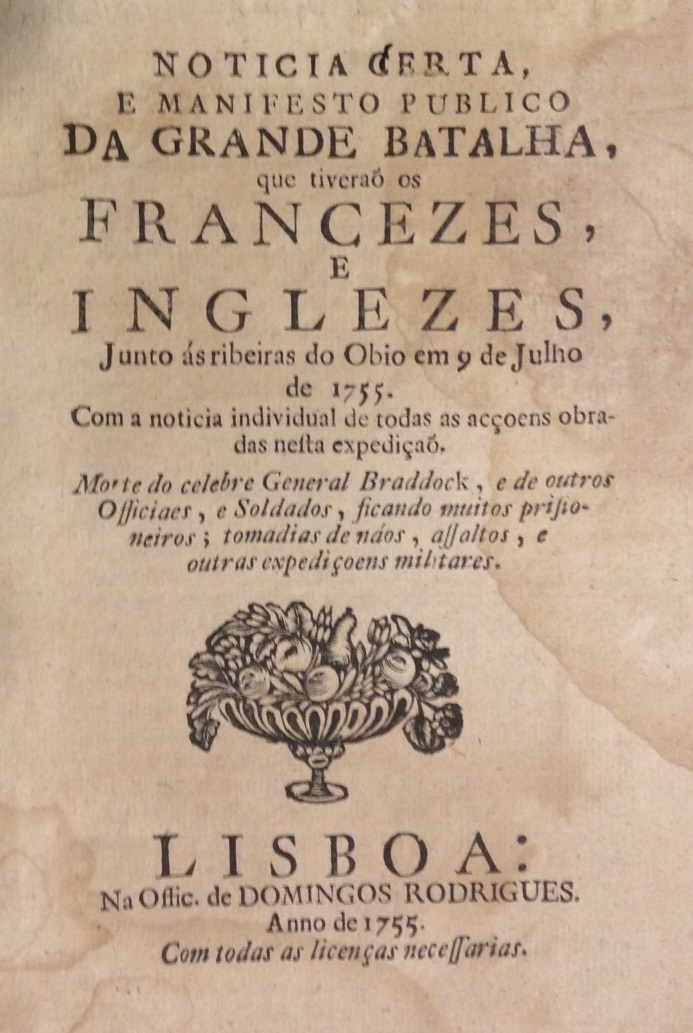

Noticia certa, e manifesto publico da grande batalha, que tiveraõ os francezes, e inglezes, junto ás ribeiras do Obio em 9 de julho de 1755. Com a noticia individual de todas as acçoens obradas nesta expediçaõ. Morte do celebre General Braddock, e de outros officiaes, e soldados, ficando muitos prisioneiros … Lisbon: Domingos Rodrigues, 1755. (A 1755 .N67)

The French and Indian War began badly for Britain. Sent to rout the French from western Pennsylvania, General Edward Braddock’s forces suffered a disastrous defeat on July 9, 1755, at the Battle of Monongahela near present-day Pittsburgh. Braddock was among the hundreds of British casualties before a young junior officer—George Washington—was able to lead an orderly retreat. The McGregor Library contains some important primary sources concerning the battle—two are included in the 75th anniversary exhibition now on view—and this very rare, ephemeral pamphlet is the latest addition. News of Braddock’s defeat spread quickly by letter, word of mouth, newspapers and other printed accounts. This newsletter conveyed the news to a Portuguese audience. Following a brief description of the battle (no mention is made of Washington, however) and the diplomatic aftermath, it lists the names of British officers who were killed or wounded.

[Thomas Cooper, 1759-1839?] Extract of a letter from a gentleman in America to a friend in England, on the subject of emigration. [London?, 1794?] (A 1792 .G45)

[Thomas Cooper, 1759-1839?] Extract of a letter from a gentleman in America to a friend in England, on the subject of emigration. [London?, 1794?] (A 1792 .G45)

Likely the first edition (of two published in England ca. 1794) of this concise description of the United States. Written from the perspective of an Englishman contemplating emigration, it offers carefully reasoned arguments for and against settling in specific states. Particular consideration is given to the frontier regions of New York and Kentucky, though the anonymous author concludes that Pennsylvania is the better option. Indeed, that is precisely where the probable author, Thomas Cooper, settled later in 1794 after touring the United States; the letter was likely addressed to, and published at the behest of, Joseph Priestley, who also emigrated to Pennsylvania in 1794. An economist and liberal political thinker, Cooper soon developed a thriving Philadelphia law practice which helped to earn him the esteem of Thomas Jefferson. In 1819 Cooper was the first professor appointed to the faculty of the as-yet-unopened University of Virginia, but he resigned in 1820 following controversy over his religious views. Later he served as president of the University of South Carolina.

Christian Gottlieb Glauber, 1755-1804. Peter Hasenclever. Landeshut, 1794. (A 1794 .G53)

Christian Gottlieb Glauber, 1755-1804. Peter Hasenclever. Landeshut, 1794. (A 1794 .G53)

Privately printed in a small number of copies, this is a biography of Peter Hasenclever, a German entrepreneur who, by establishing several business enterprises in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and New York between 1764 and 1769, became Colonial America’s leading industrialist. With the coming of peace following the Seven Years’ War, Hasenclever raised over £50,000 from English backers to open a network of iron mines and ironworks and a potash manufactory, and to raise hemp and harvest timber. His enterprises were staffed by the over 500 German workers who heeded his invitation to emigrate. Hasenclever spent lavishly on his businesses, only to be plunged into bankruptcy in 1769 when his English partners withdrew financial support. After returning to Germany, Hasenclever was able to rebuild his fortune in the textile trade. The biography concludes with a lengthy appendix of letters written by Hasenclever during his American sojourn.

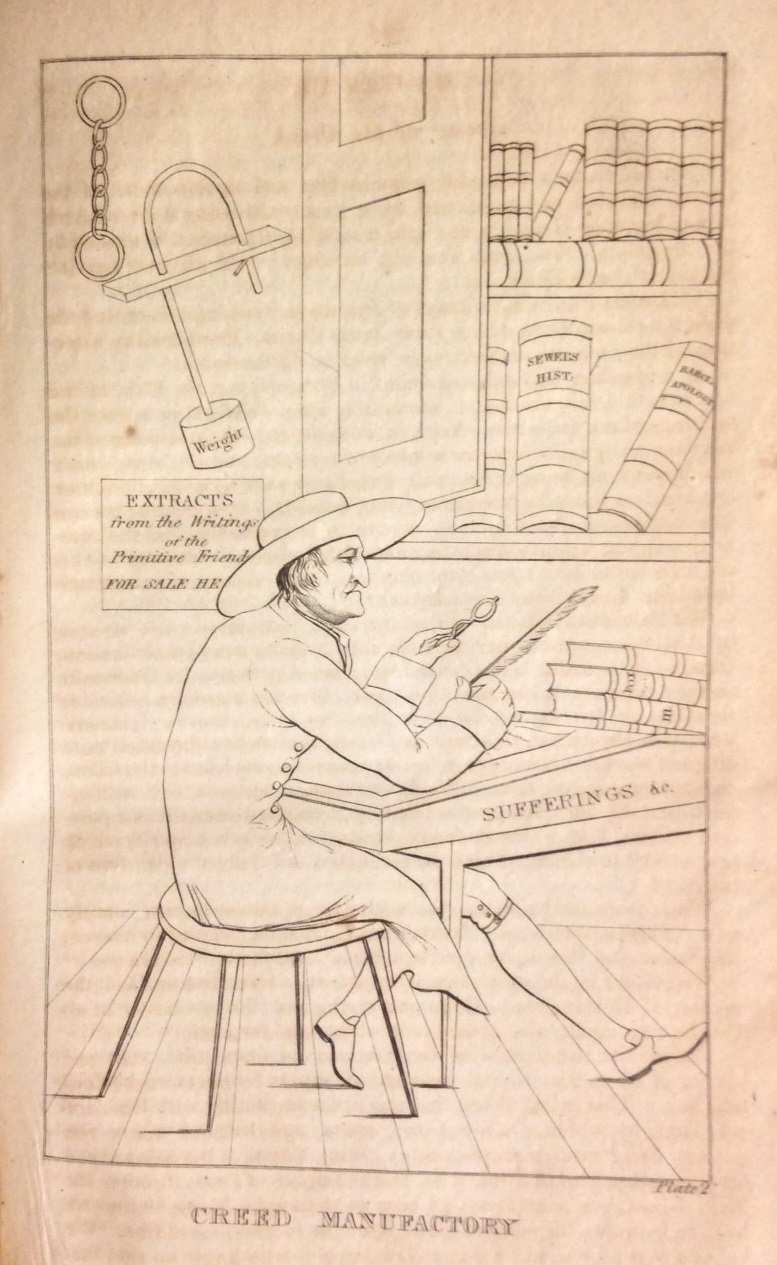

Hole in the wall; or A peep at the creed-worshippers. [Philadelphia], 1828. (A 1828 .H65)

Hole in the wall; or A peep at the creed-worshippers. [Philadelphia], 1828. (A 1828 .H65)

This rare and unusual tract was an important salvo in the bitter schism, or “Great Separation,” between orthodox Quakers and their Hicksite adversaries. By the 1820s significant tensions had arisen between Philadelphia’s wealthy Quaker merchants and the Quaker farmers of southeastern Pennsylvania, who were attracted to the teachings of Elias Hicks—tensions comparable to those between New England Congregationalists and Unitarians. Unable to settle their differences at the 1827 Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, the two camps set up competing Meetings, with the orthodox Quakers adopting and enforcing a doctrinal creed. This pamphlet, which vigorously promotes the Hicksite view, is “embellished” with three accomplished satirical engravings by the anonymous author.

Frances Wright (1795-1852). Course of popular lectures, historical and political, Vol. II. As delivered by Frances Wright Darusmont, in various cities, towns and counties of the United States. Philadelphia: Published by the author, 1836. (A 1836 .W75)

Frances Wright (1795-1852). Course of popular lectures, historical and political, Vol. II. As delivered by Frances Wright Darusmont, in various cities, towns and counties of the United States. Philadelphia: Published by the author, 1836. (A 1836 .W75)

During the 1820s and 1830s, Fanny Wright was perhaps the most notorious woman in the United States. Born in Scotland, Wright visited the United States from 1818-1820, recording her observations in the bestselling Views of society and manners in America (1821). Having befriended Lafayette, Wright accompanied him on much of his 1824-1825 tour of America. She then launched a career as a radical political and social reformer. An ardent feminist, freethinker, and friend of labor, Wright visited Robert Owen’s utopian community at New Harmony, Ind., before setting up her own settlement, Nashoba, near Memphis. The objective of this multi-racial community was to promote the abolition of slavery by preparing slaves for freedom. By 1830 it had failed, and Wright henceforth promoted her views through journalism and a career as America’s first prominent female public speaker. This very rare pamphlet in its original wrappers prints the text of three lectures from Wright’s 1836 lecture tour: two praise Jefferson’s vision of an agrarian republic and condemn the contrasting Hamiltonian vision, and a third outlines her abolitionist views.

Robert Hubbard (1782-1840). Historical sketches of Roswell Franklin and family: drawn up at the request of Stephen Franklin. Dansville, N.Y.: A. Stevens for Stephen Franklin, 1839. (A 1839 .H85)

Robert Hubbard (1782-1840). Historical sketches of Roswell Franklin and family: drawn up at the request of Stephen Franklin. Dansville, N.Y.: A. Stevens for Stephen Franklin, 1839. (A 1839 .H85)

A rare and very early work of American local history, published in a small town some 40 miles south of Rochester, N.Y. Written by the local minister at the behest of the Franklin family, most of the book is a biography of the family patriarch, Roswell Franklin (d. 1791 or 1792), drawn primarily from family oral tradition. Born in Woodbury, Conn., Franklin fought for the British in the West Indies and Cuba before moving his family to northeastern Pennsylvania’s Wyoming Valley in 1770. With the outbreak of revolution, Franklin and his fellow patriots found themselves in a frontier war zone, besieged by British forces and their Iroquois allies. Included here is a vivid account of the 1778 Battle of Wyoming, in which Franklin was one of few patriots to survive. Subsequent chapters describe the family’s role as pioneers, following the expanding frontier northwestward into west central New York, and the tremendous contrasts between Roswell Franklin’s time and America in 1839.

![Clockwise from top left, these Reds Riding Hoods appear in the following books, which are not yet cataloged: "Little Red Riding Hood, (London: Tuck, [1890]); "Les Contes de Perrault" (Paris: Librairie de Theodore Lefevre, n.d.); "Walter Crane's Toy Books: Little Red Riding Hood" ([London]: George Routledge, n.d.); "Rotkappchen" (n.p: n.p., n.d.). [xx(6134166.1). Photograph collage by Molly Schwartzburg]](https://smallnotes.library.virginia.edu/files/2013/09/LRRH.jpg)

![Clockwise from top left, these wolves appear in the following books, which are not yet cataloged: "Rotkappchen" (n.p: n.p., n.d.); "Tales of Passed Times Written for Children by Mr. Perrault and Newly Decorated by John Austen" (London: Selwyn and Bount, 1922); "Little Red Riding Hood, (London: Tuck, [1890]); "Walter Crane's Toy Books: Little Red Riding Hood" ([London]: George Routledge, n.d.).](https://smallnotes.library.virginia.edu/files/2013/09/Wolf.jpg)