Welcome to our most recent installment of the ABCs of Special Collections, where the featured letter is

I is for Italian Palatino (1566). Lewis F. Day. Alphabets Old and New: Containing Over One Hundred and Fifty Complete Alphabets….London: B. T. Batsford, 94 High Holborn, 1898. (Typ 1898. D39. Stone Typography Collection. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

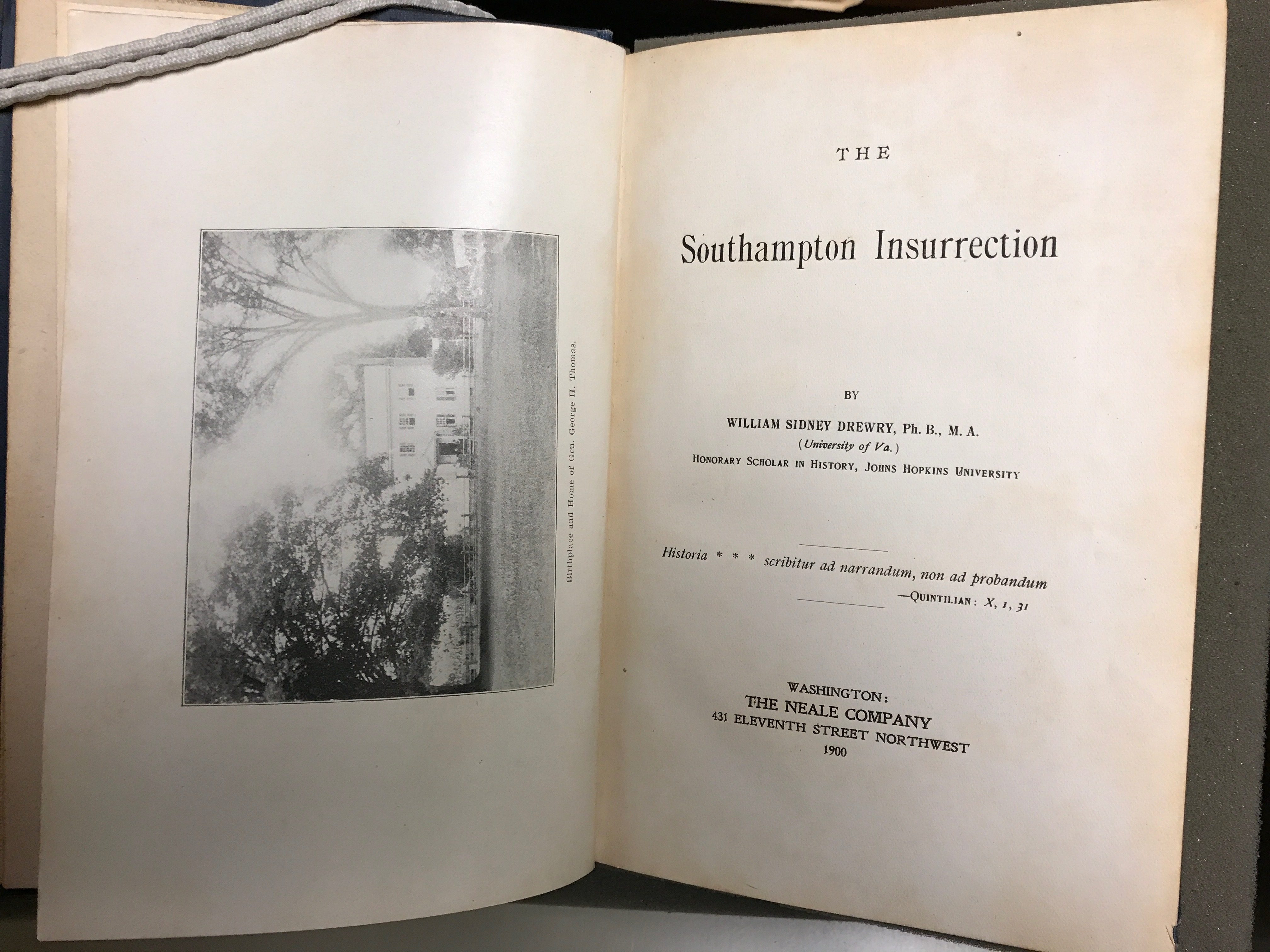

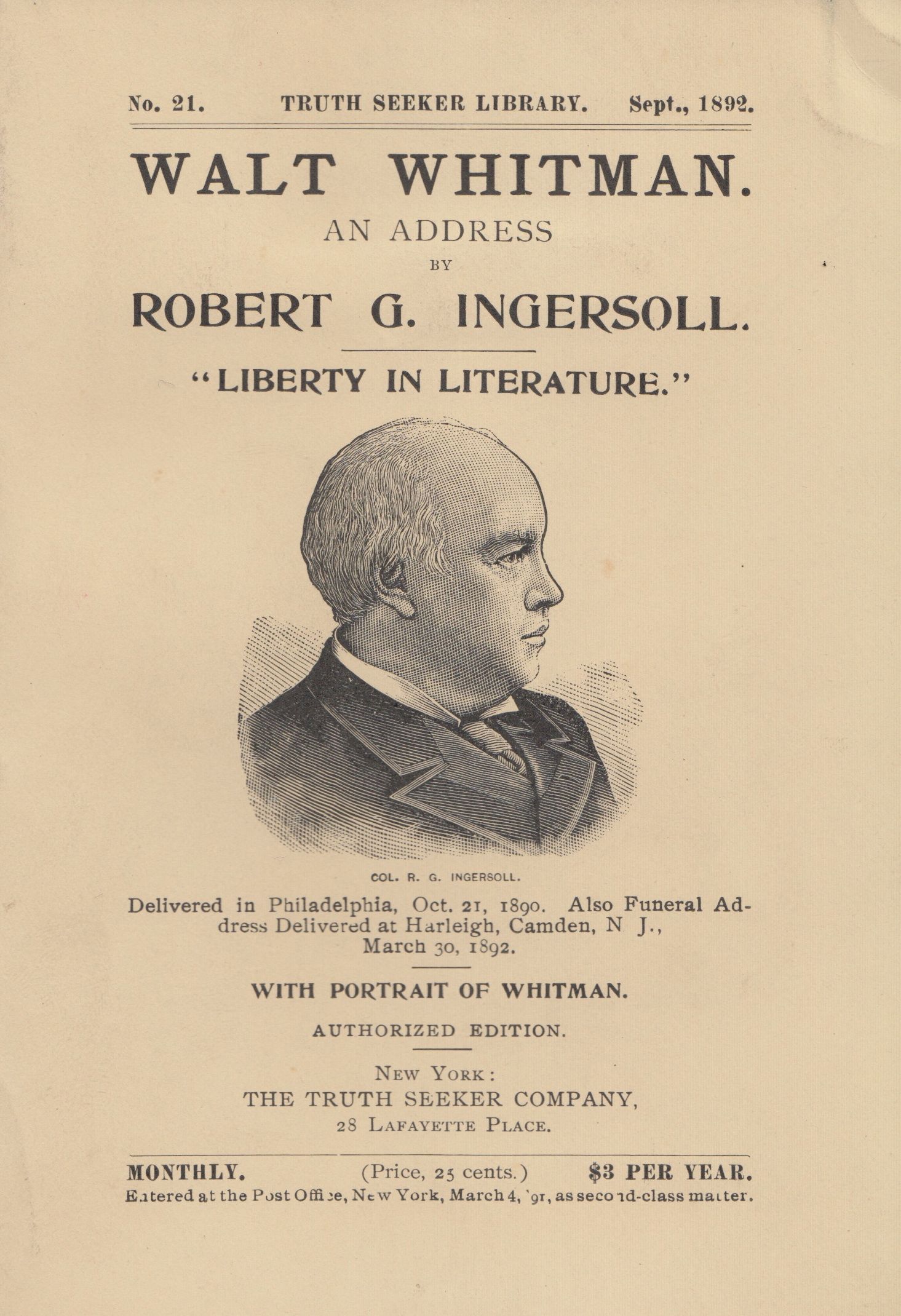

I is for Robert Ingersoll

Robert Ingersoll, the great American 19th-Century orator, was popularly known as “The Great Agnostic.” An attorney by trade, Ingersoll, by virtue of his oratory skills, kept paying audiences enthralled for hours as he weighed in on controversial subjects, political, social, and moral. Walt Whitman considered Ingersoll the greatest orator of his time. Whitman wrote, “It should not be surprising that I am drawn to Ingersoll, for he is Leaves of Grass. He lives, embodies, the individuality, I preach.” Ingersoll delivered the eulogy at Whitman’s funeral in 1892.

Contributed by George Riser, Collections and Instruction Assistant

Shown is the cover of an 1892 edition of Walt Whitman. An Address by Robert G. Ingersoll. “Liberty in Literature.” (PS 3232 .I5 1892. Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature. Image by Petrina Jackson)

I is for Ingles

Mary Draper Ingles was an early frontier settler in southwest Virginia. In 1755 during the French and Indian War, the settlement of Draper’s Meadow was raided by a group of Shawnee warriors. Several settlers were killed and five hostages were taken, including Mary and her two young sons, Thomas and George. The Indians forcefully led the hostages through the wilderness to an area near Big Stone Lick, Kentucky. Mary was separated from her sons and became enslaved to the Shawnee, but later escaped. She made her way on foot over hundreds of miles back to Virginia. One of her sons died in captivity and the other remained with the Shawnee for many years. Ingles relayed her ordeal to another son, John Ingles, whose hand-written manuscript of her narrative is held in Special Collections. Over the years the story of Mary Draper Ingles has been adapted to theatre, film, and historical fiction.

Contributed by Margaret Hrabe, Reference Coordinator

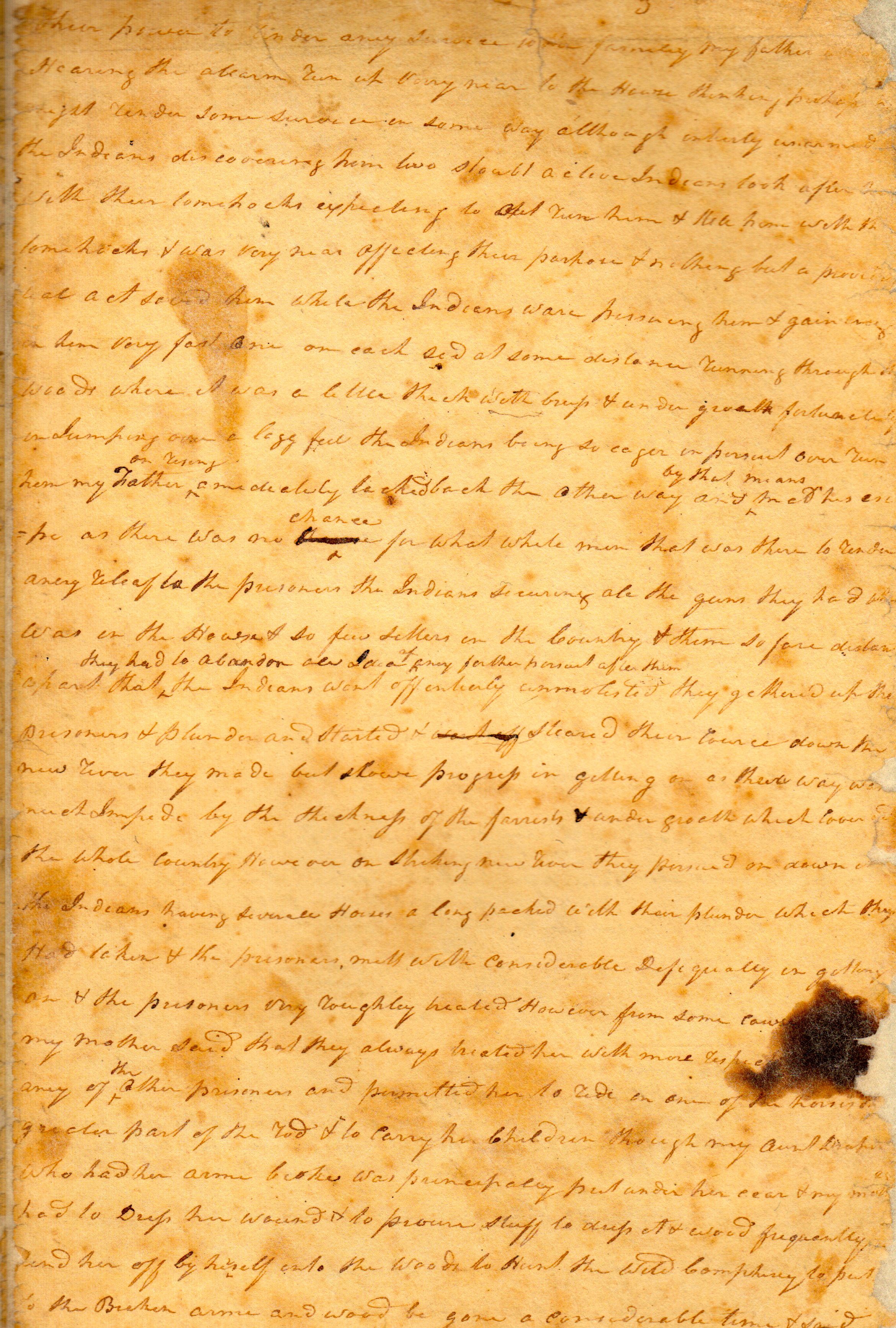

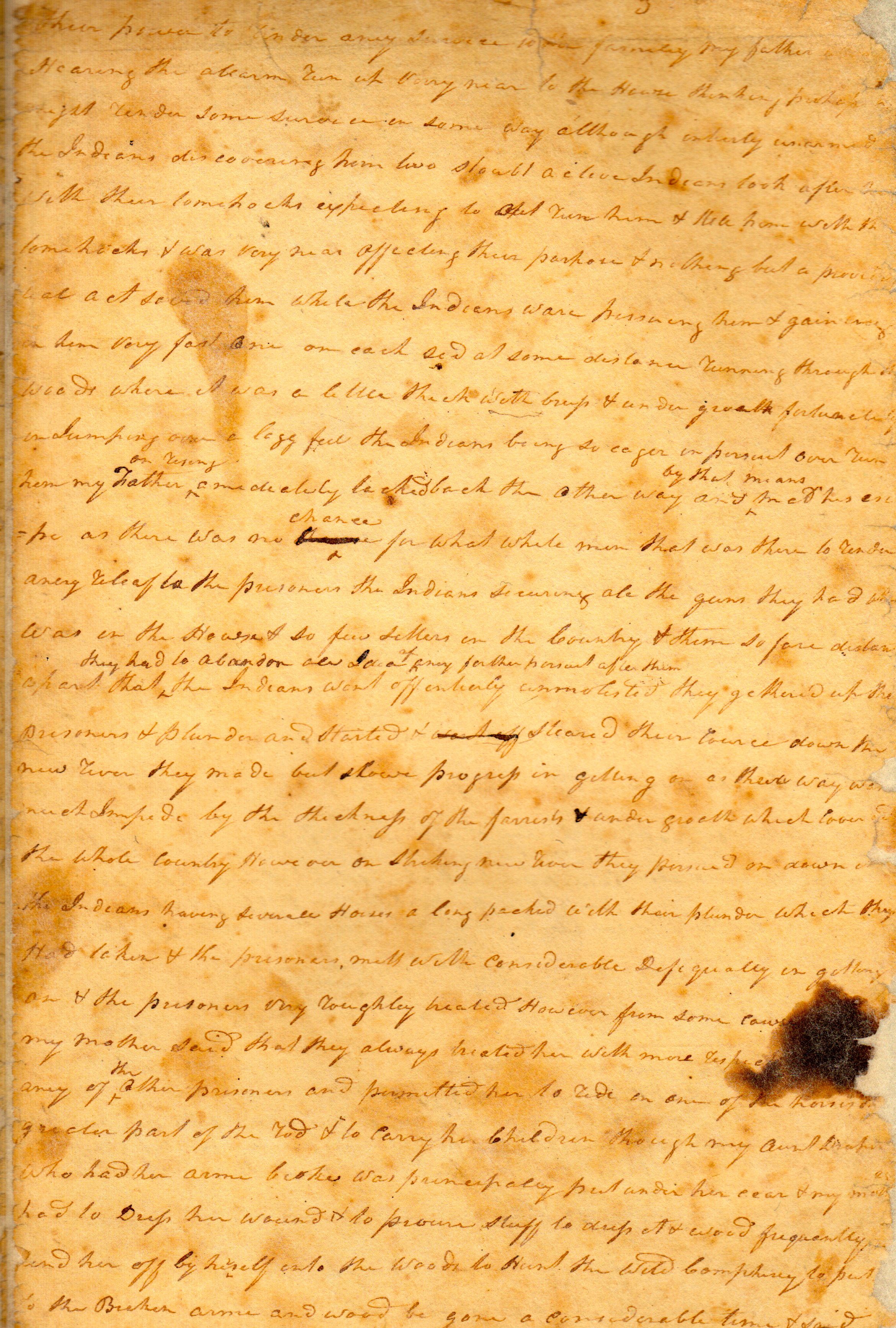

Page 3 of John Ingles’ handwritten manuscript, which was later published as a Escape From Indian Captivity: The Story of Mary Draper Ingles and son Thomas Ingles, ca. 1825. (MSS 38-246. Image by Petrina Jackson)

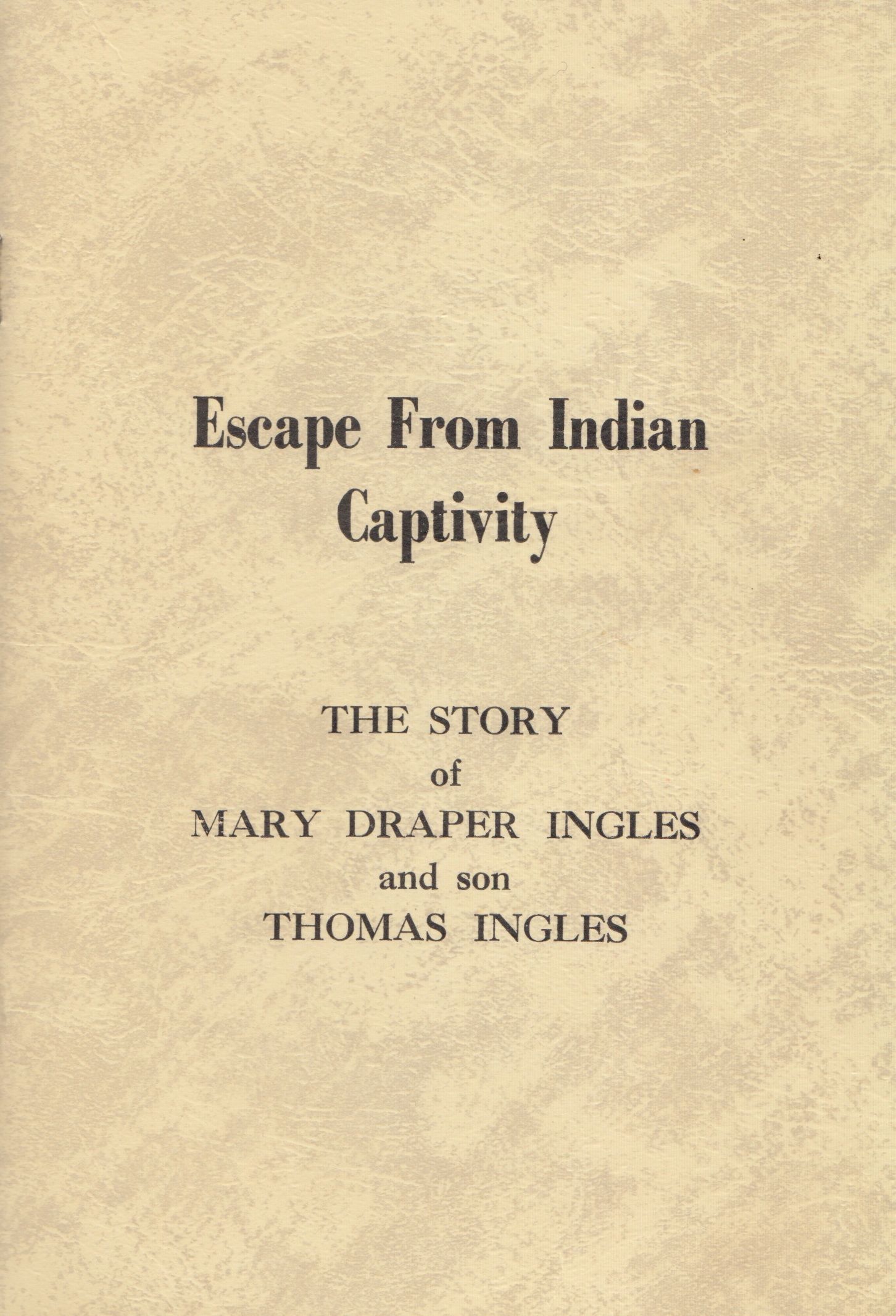

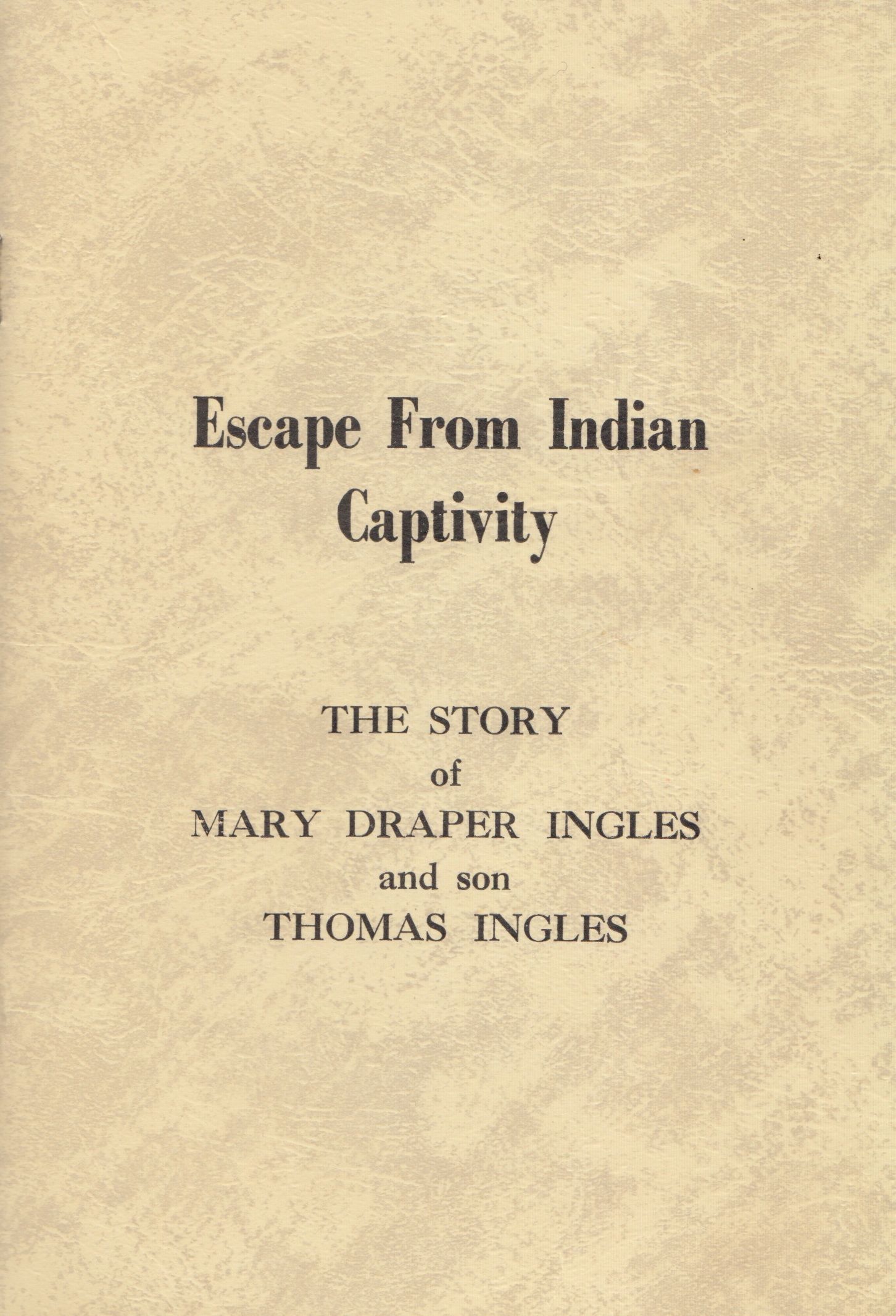

Cover of the first edition of Escape from Indian Captivity: The Story of Mary Draper Ingles and son Thomas Ingles, 1969. (E87 .I53 1969. Gift of Mrs. R. I. Steele. Image by Petrina Jackson)

Cover of The Long Way Home by Earl Hobson Smith (1976). The Long Way Home was an outdoor historical drama adaptation of the story of Mary Draper Ingles’ capture by and escape from the Shawnee Indians. (PS 3537 .M346 L56 1976. Robert and Virginia Tunstall Trust Fund 2006/2007. Image by Petrina Jackson)

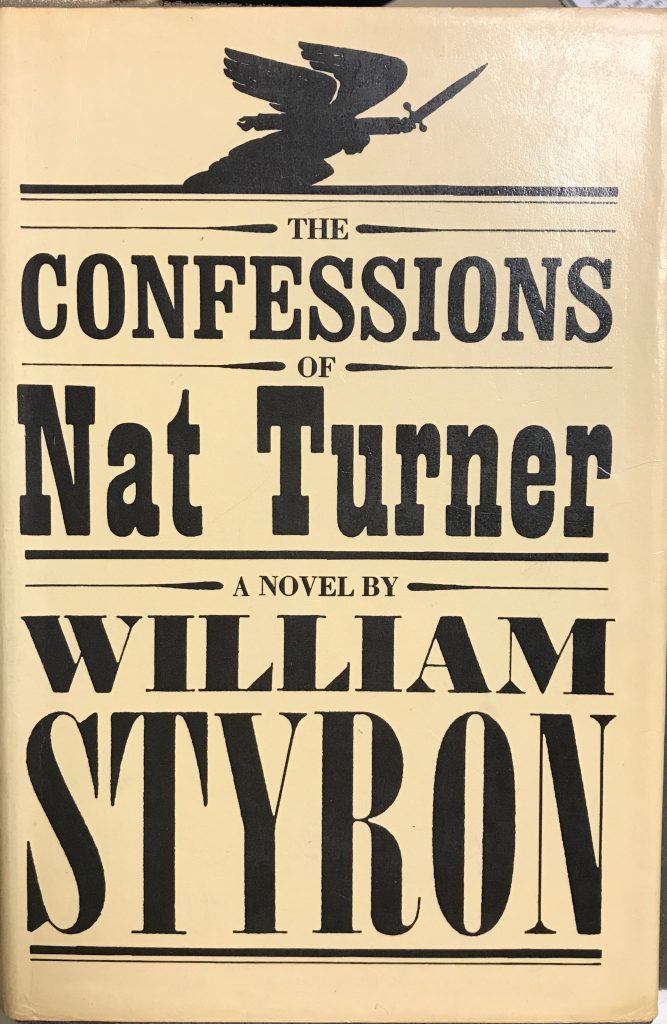

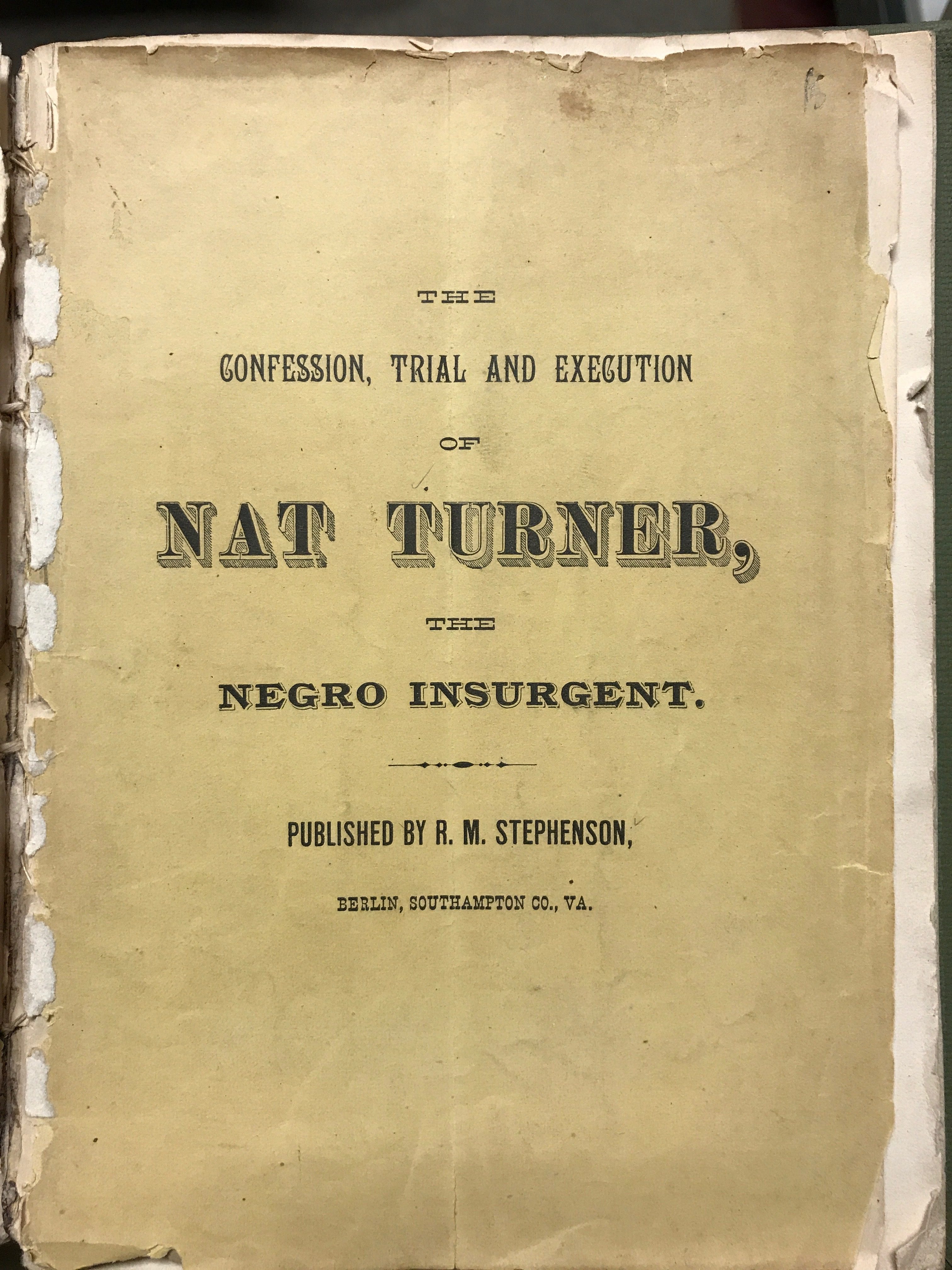

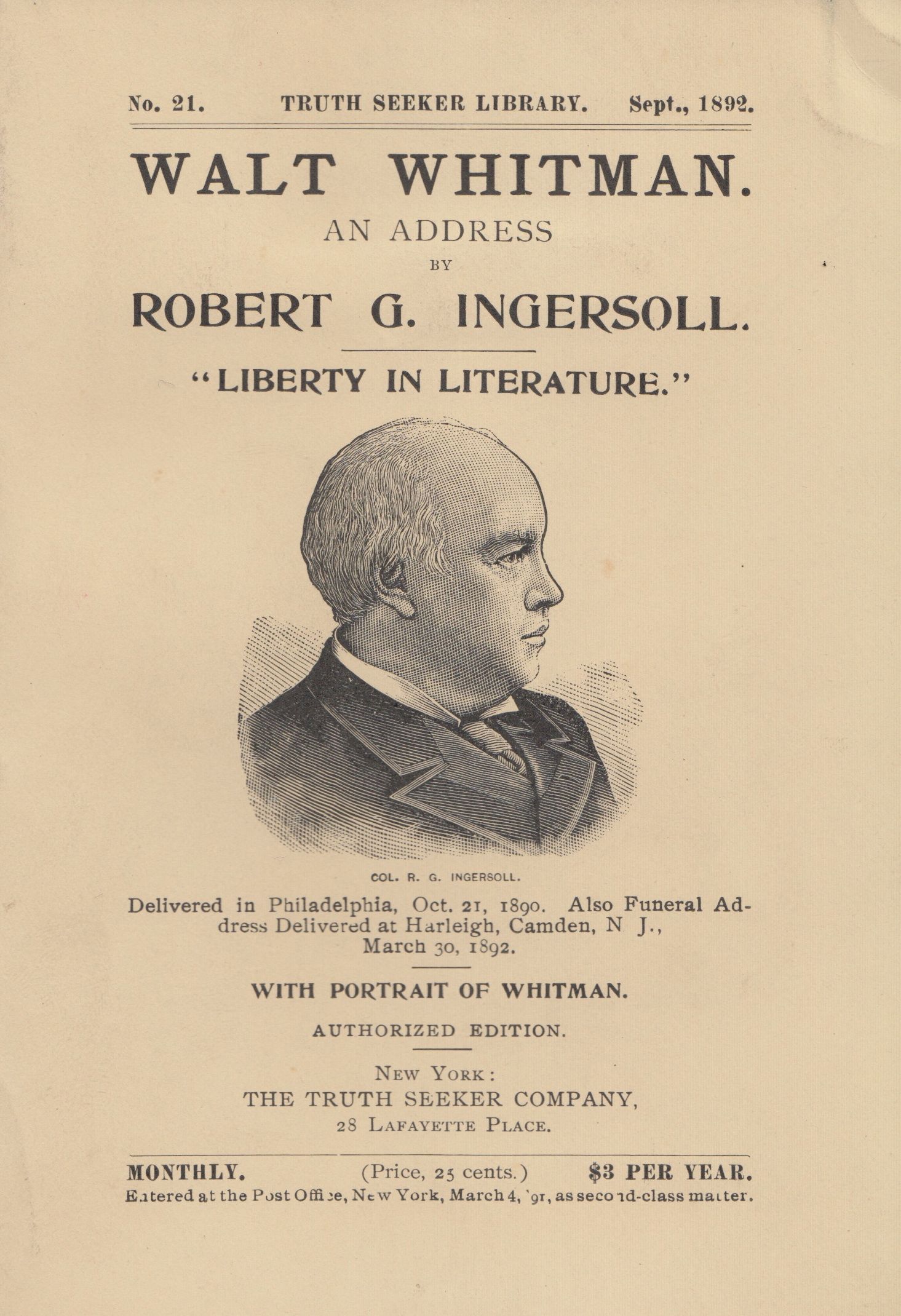

I is for Insurrection

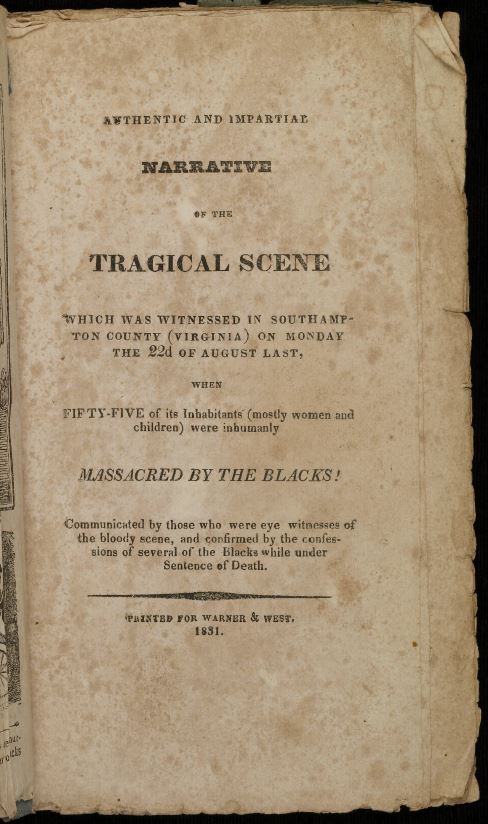

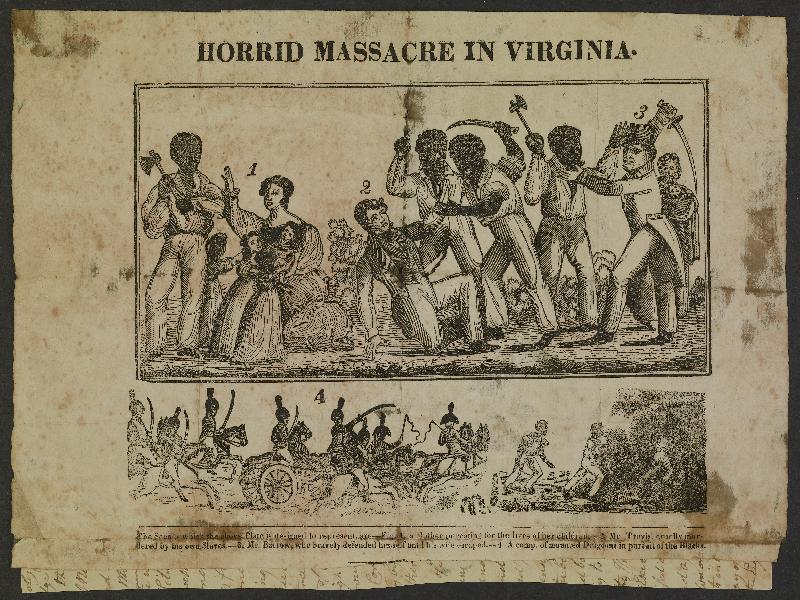

On August 21, 1831, Nat Turner raised the largest slave rebellion in U.S. history in Virginia’s Southampton County. The slave force massacred over 60 white men, women, and children. The rebellion was brutally suppressed and an orgy of violence followed, in which over 200 African Americans were executed by the state and murdered by vigilante groups. The Southampton Insurrection spread fear and hysteria across the South and as a result, Virginia and other Southern states passed harsh new laws that further restricted the activities of both slaves and free blacks.

Contributed by Edward Gaynor, Head of Description and Specialist for Virginiana and University Archives

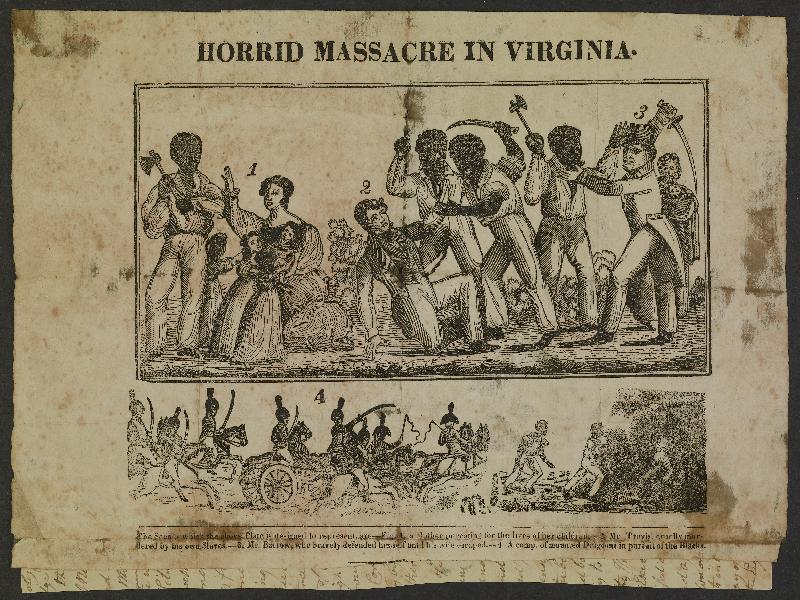

Horrid Massacre of Virginia: Just Published, an Authentic and Interesting Narrative of the Tragical Scene which was Witnessed in Southampton County (Virginia), on Mondy the 22d of August Last, when Fifty Five of its Inhabitants (Mostly Women and Children) were Inhumanly Massacred by the Blacks! (Broadside 1831. W377. Tracy W. McGregor Library of American History. Image by Digitization Services)

Photographs of Nat Turner’s Bible and Cross Keys (showing old store house in which some of the insurgents were imprisoned), ca. 1900. (MSS 10673. Image by Petrina Jackson)

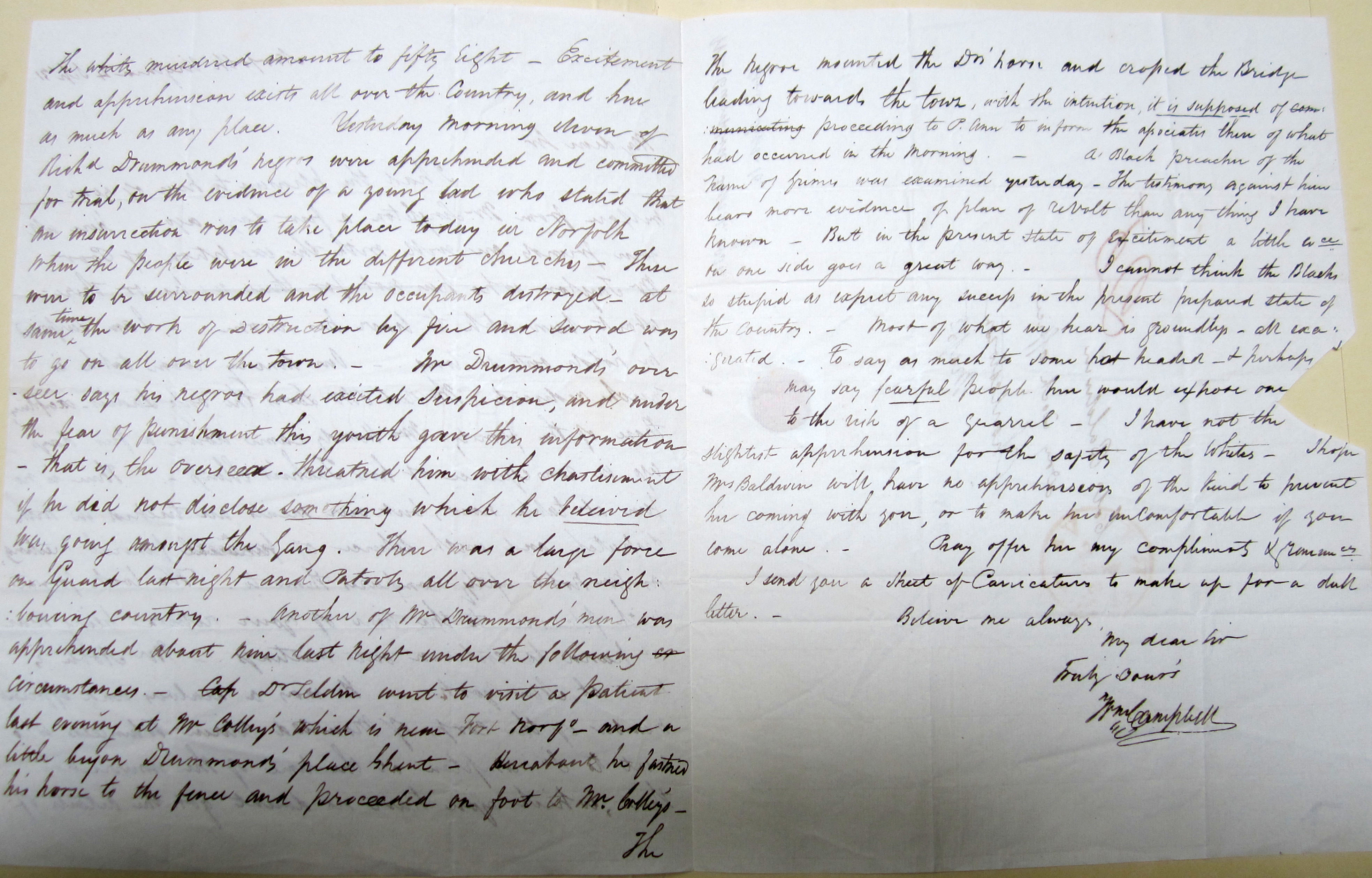

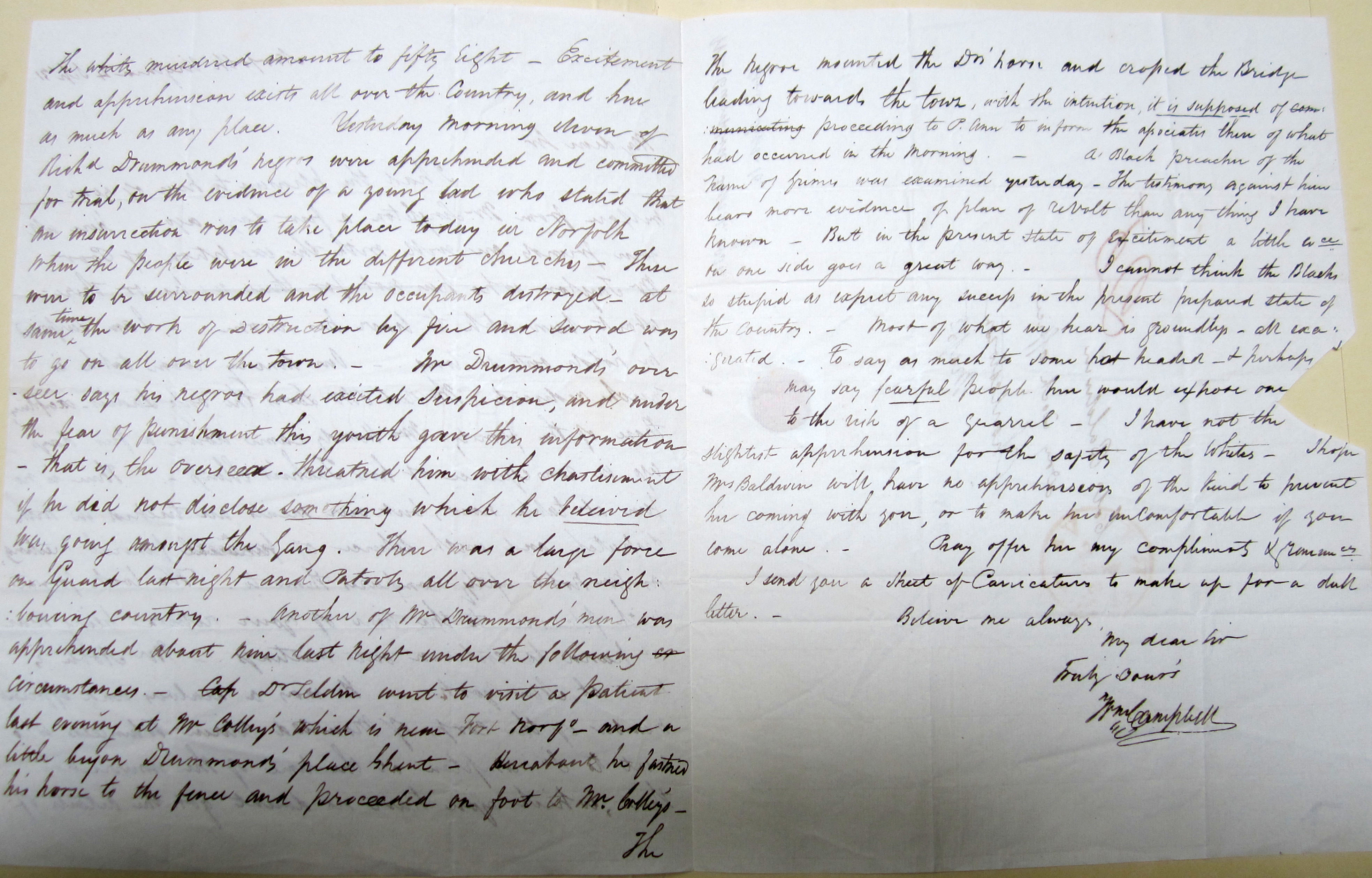

Letter from William Campbell to Col. Baldwin detailing the effects of the Southampton insurrection. The letter mentions Richard Drummond’s eleven arrested slaves and the Corps of Mounted Citizen Volunteers, 4 September 1831. (MSS 1441. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

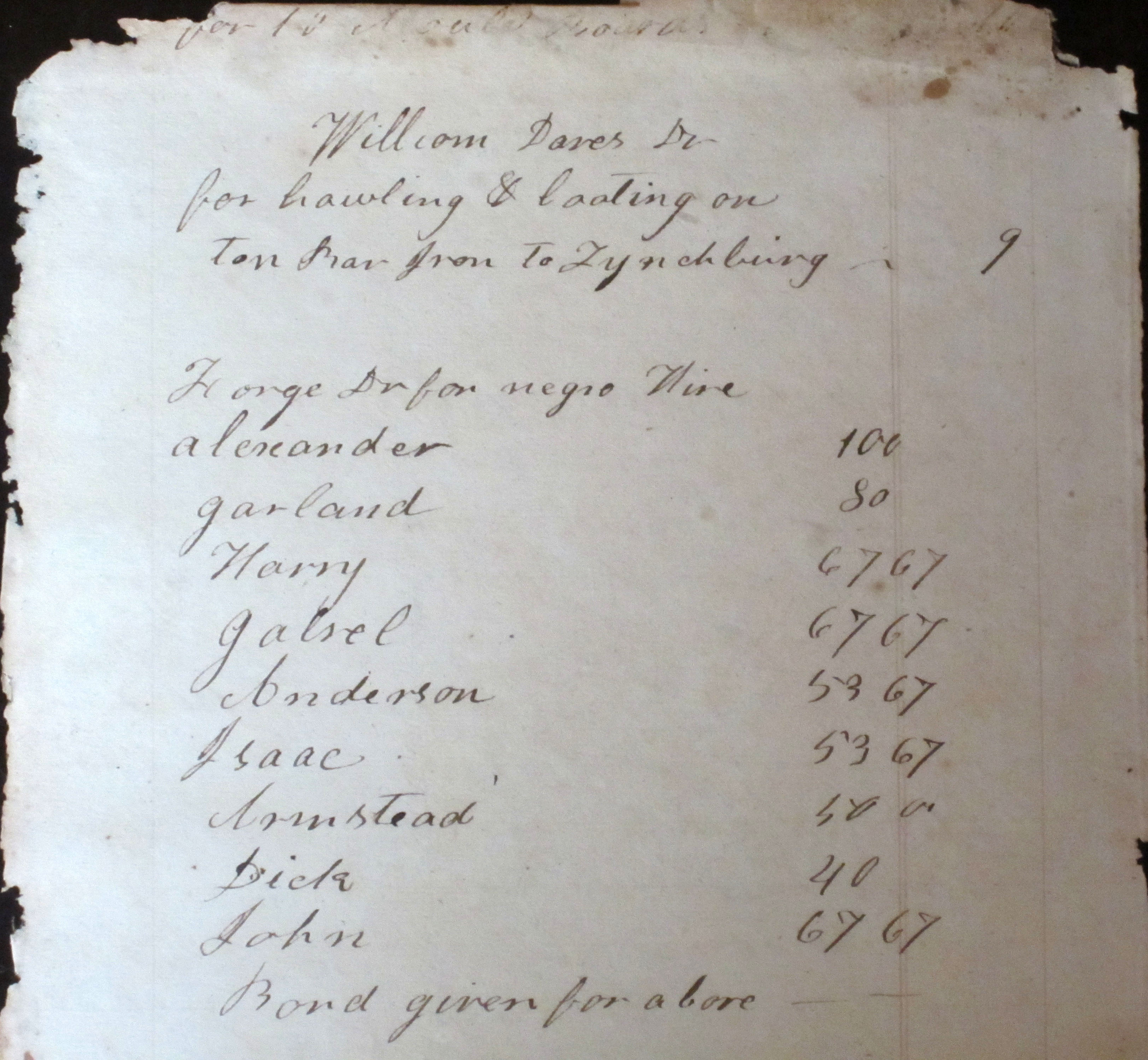

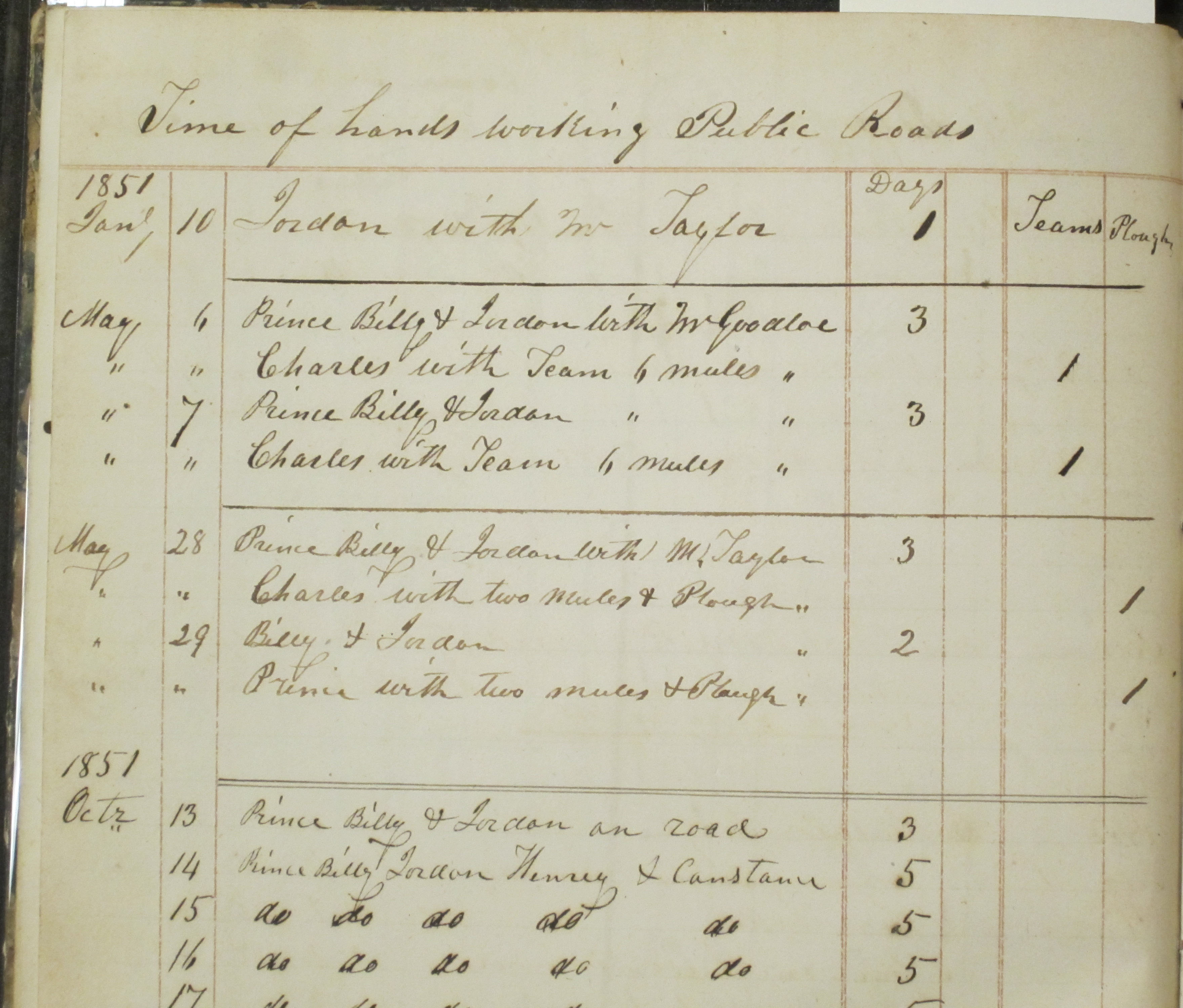

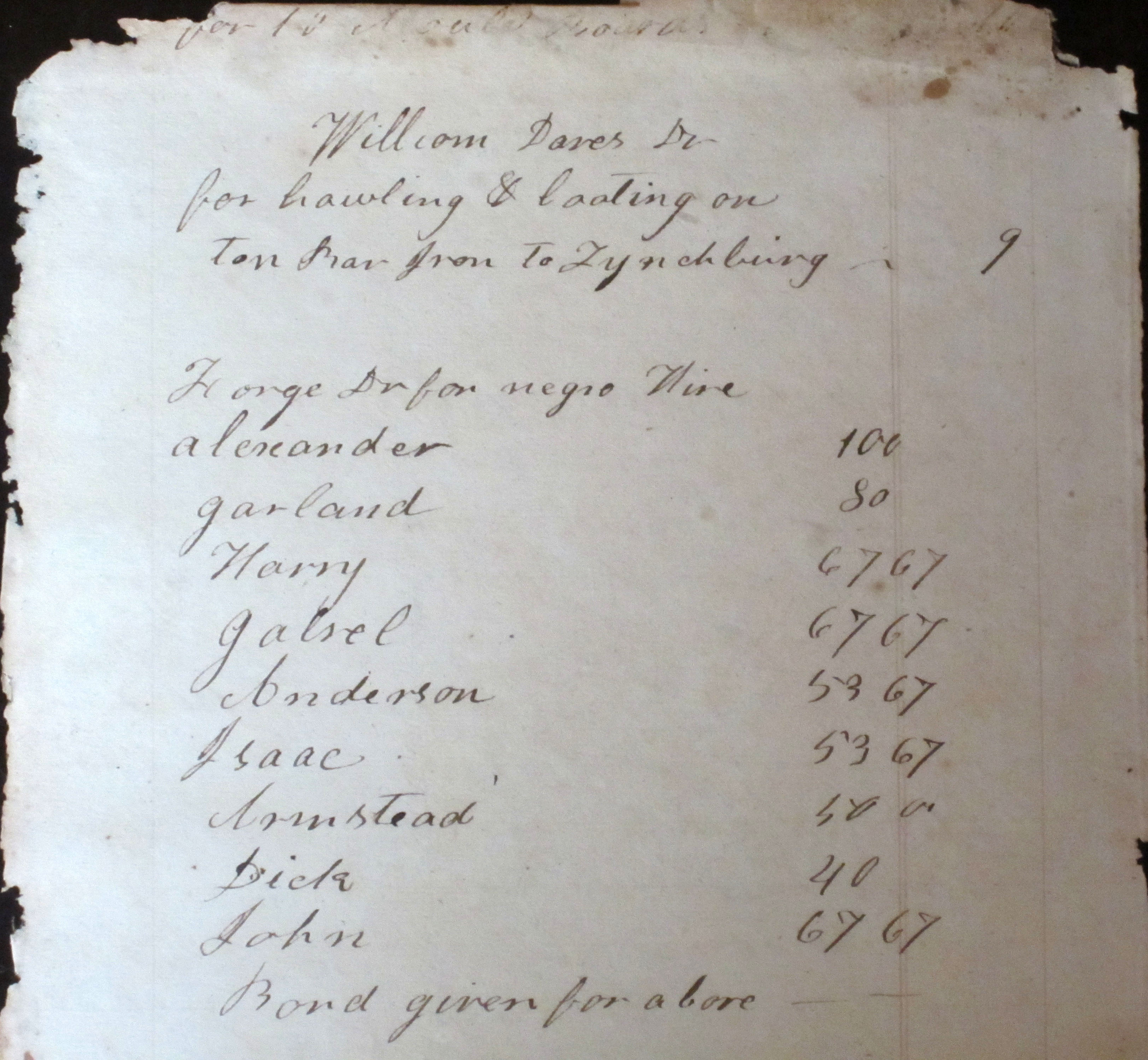

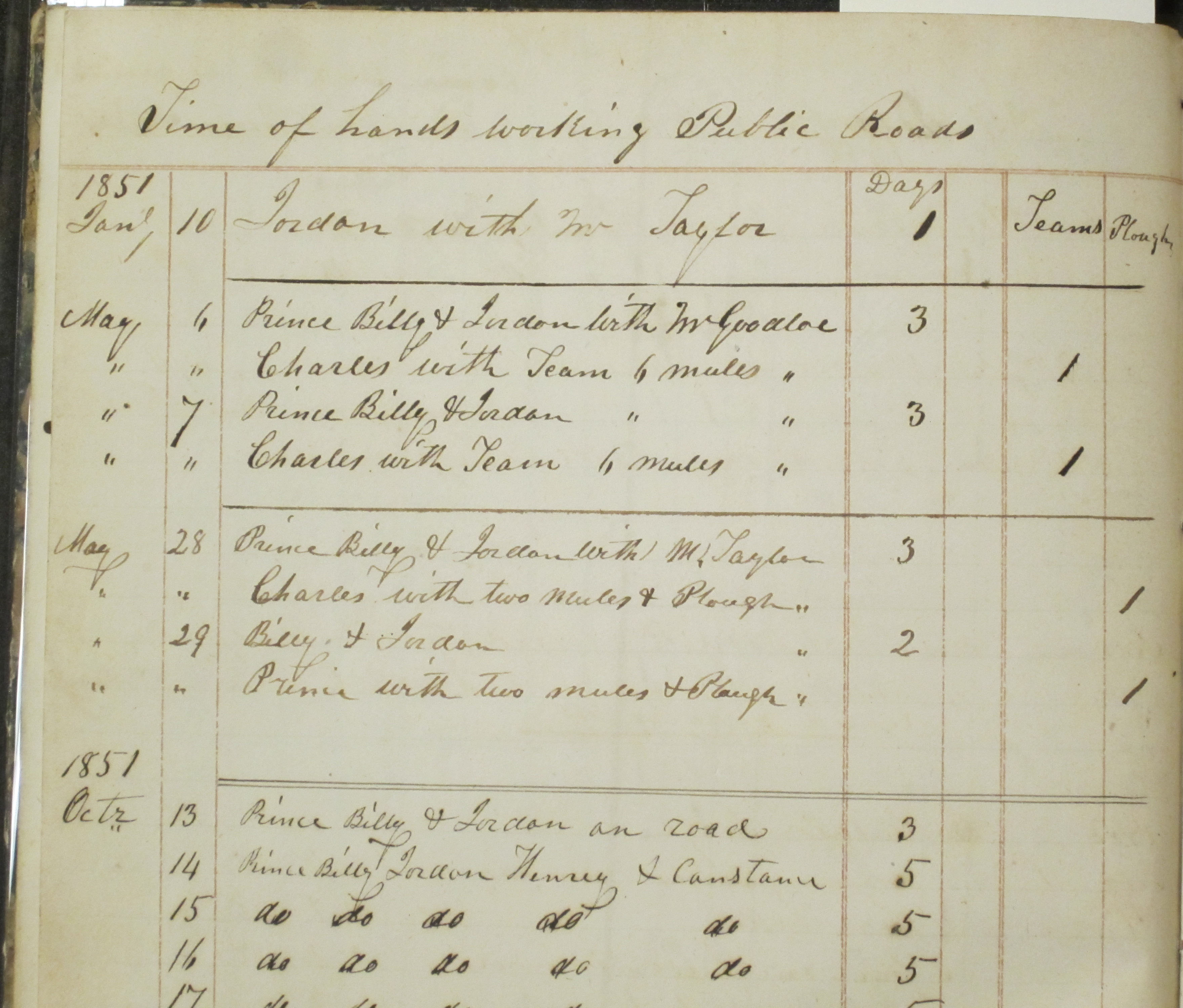

I is for Iron

The Weaver-Brady family papers document what is to many, one of the more surprising aspects of slavery in Virginia: the use of slaves in heavy industry. William Weaver built a network of iron producing operations in the Shenandoah Valley that included two forges, two blast furnaces and nearly 20,000 acres of land from which his 170 slaves harvested iron ore and timber. Nearly every job at the forges–from the most skilled to the least–was held by slaves. Operations such as Weaver’s led the way in establishing industrial slavery as a viable future direction as agricultural needs declined.

Contributed by Edward Gaynor, Head of Description and Specialist for Virginiana and University Archives

A page, featuring debits for “Negro hires” from volume 2 of Buffalo and Bath Forge and Furnace account books. (MSS 38-98-d. Coles Special Collections Fund. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

A page, featuring the time records for “hands” from volume 3 of the Buffalo and Bath Forge and Furnace account books. (MSS 38-98-d. Coles Special Collections Fund. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Cover of Bond of Iron: Master and Slave at Buffalo Forge by Charles B. Dew, 1994. (F234 .B89 D48 1994. Coles Fund 1998/1999. Image by Petrina Jackson)

That is all for “I.” Come back in a couple weeks for the letter “J.” I bet you have a “J” in mind already!