This is the first in a series of four posts, spotlighting the mini-exhibitions of students from USEM 1570: Researching History.

Last fall semester, I had the pleasure of teaching USEM 1570: Researching History, a course I designed with the purpose of introducing undergraduates to the wonderful, yet painstaking world of primary source research. Sixteen undergraduates took on the challenge of the class and for a semester were immersed in searching for, finding, and evaluating the wealth of materials in Special Collections. Their final assignment was to create a mini-exhibition, telling a particular story with only five items of varying formats. After creating the exhibitions, they presented them at their outreach program, Tales from Under Grounds. The program was a success! I wish everyone could have been there to see their great work.

USEM student Adam Hawes does a practice presentation of his mini-exhibition as his classmates look on.

For those who could not make it, I present to you the second best thing: Tales from Under Grounds in its abridged version as captured in each student’s own words.

Note: only two selections per student are shown.

***

Jenna Parker, First-Year Student

Photograph of Jenna Parker by Sanjay Suchak, 19 November 2013.

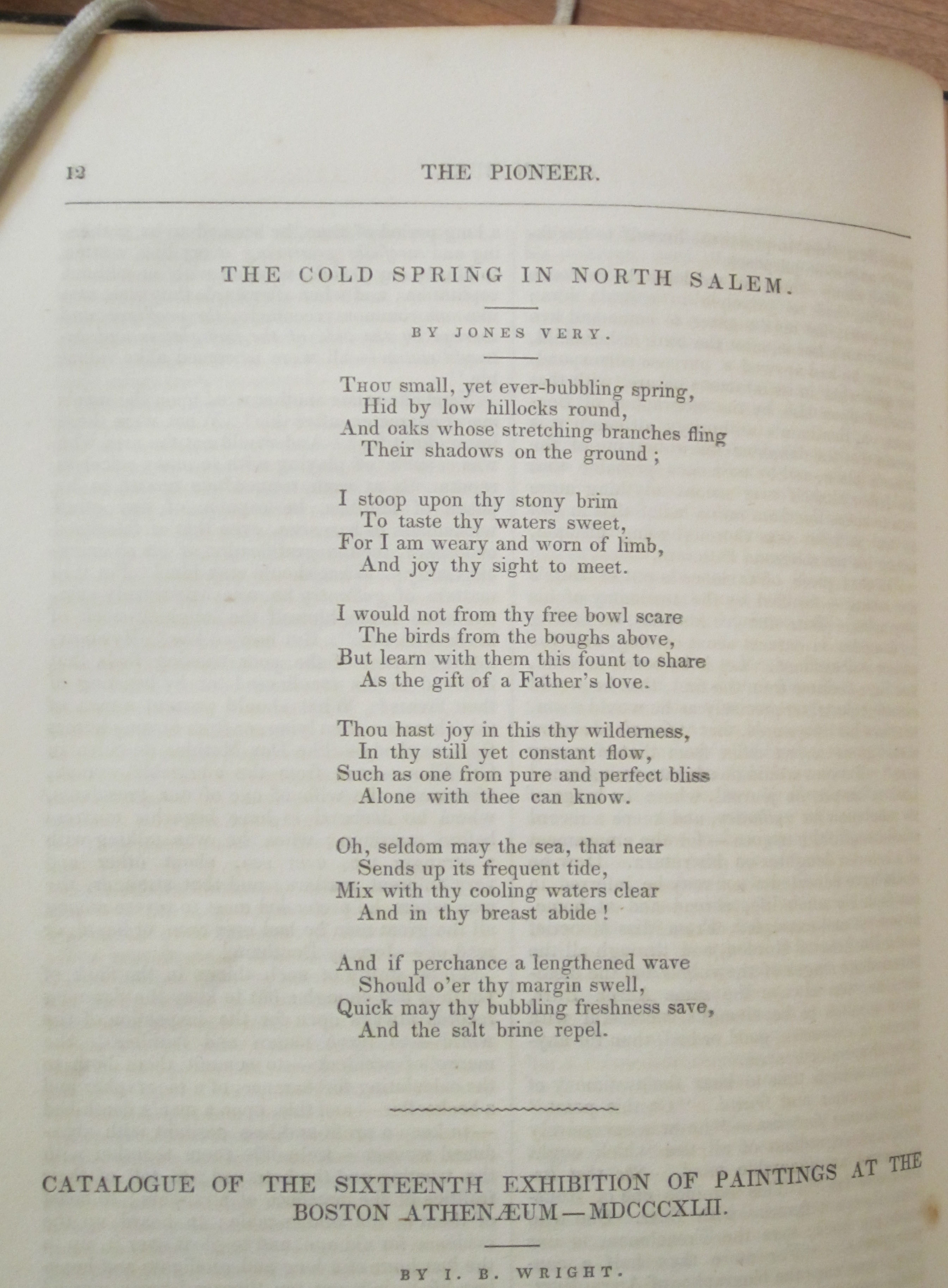

Bottoms Up: Drinking in America in the 19th and Early 20th Centuries

Despite the various Temperance Movements in the United States in the 19th century, drinking was always a very popular part of American society, and attempts to curb the American cultural trait of drinking just popularized the habit even more. It was not an uncommon practice for drinking to start at breakfast and for children to drink as well.

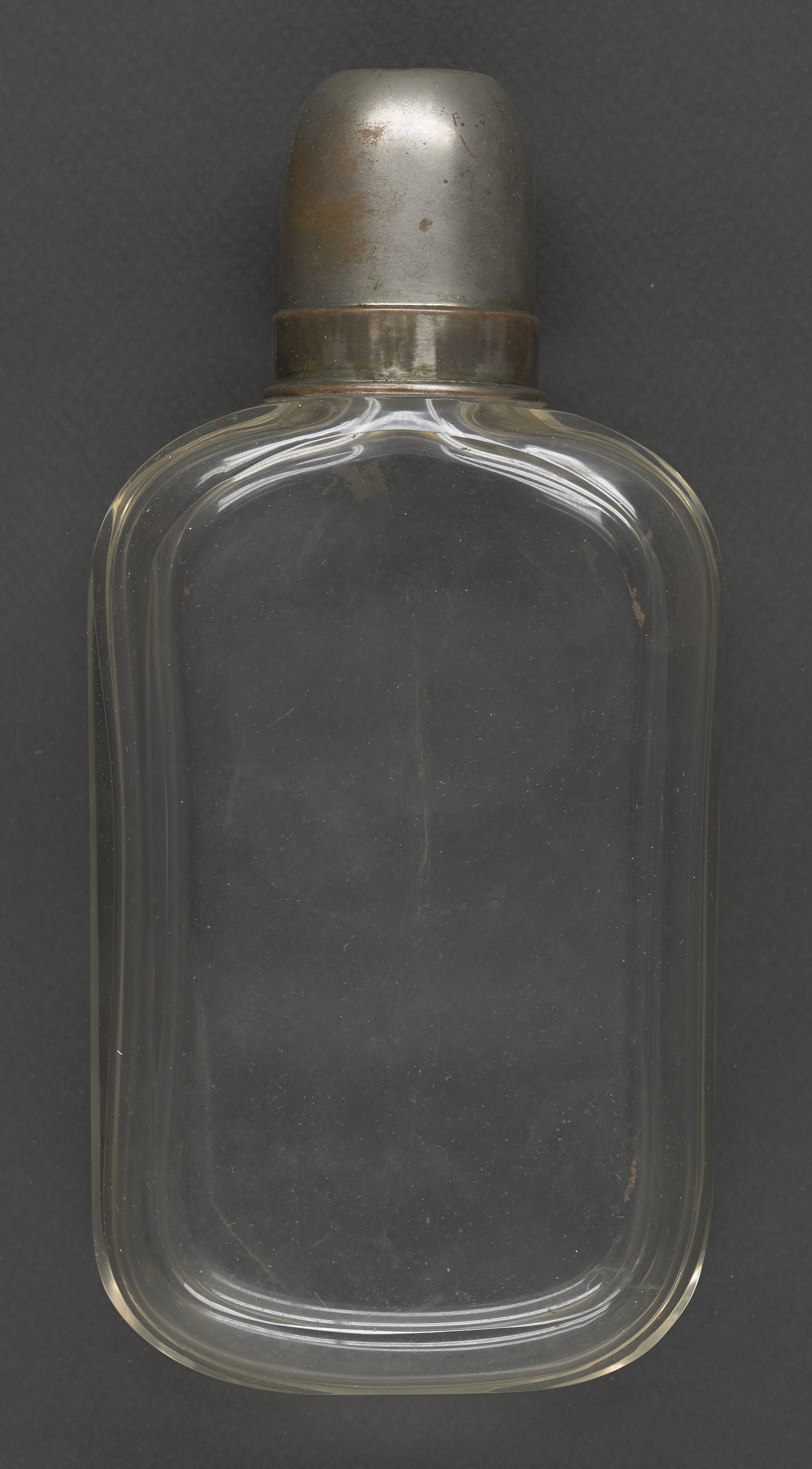

This display showcases a unique recipe for beer from Thomas Jefferson, a cookbook with numerous recipes for alcoholic beverages, a musical score from a popular drinking song, Charles Dickens’ liquor flask, and alcohol trade catalogs. These items serve to demonstrate how commonplace drinking was in American culture and society at a time when drinking was both expected and discouraged.

Charles Dickens’s Glass Liquor Flask. This glass spirit flask is the one that the famous British author Charles Dickens carried with him while he was traveling in the United States. (MSS 10562. Image by Digitization Services)

A note from Charles Dickens to his sister-in-law and housekeeper Georgina Hogarth with household instructions, which was included with the flask. (MSS 10562. Image by Digitization Services)

A note from Georgina Hogarth certifying the authenticity of the flask.(MSS 10562. Image by Digitization Services)

These trade catalogs are from around 1887-1914, and advertise liquor from Heller Bros., the “Oldest, Largest, Leading, and most Prompt Mail Order Liquor Merchants and Wholesale Beer Agents in the South”. The company was based in the city of Bristol, VA-TN. (TS199 .A5 A6 no. 01. Albert H. Small American Trade Catalogs Collection. Image by Petrina Jackson)

***

Aaron Clyman, First-Year Student

Photograph of Aaron Clyman by Sanjay Suchak, 19 November 2013.

Cannabis Calumny in Capitalist America

This exhibit focuses on the relationship between the United States and the plant cannabis. This includes, the more commonly known form, marijuana, and industrial hemp, which are quite different despite being legally lumped together. The majority of the items in the exhibit regard misinformation that the public has been given regarding this political issue.

The main focus of these items should be the various scientific aspects because, as this is a highly factual issue, they must be held in the highest regard. Inside many items there are scientific studies, complete or partial, which have unanimous conclusions contrary to general notions on the matter. In this lies the true issue, people making decisions on misinformation, which inevitably leads to the misinformed policy seen today.

Pot Art by stone mountain, published by Apocrypha Books, 1970. This book is a collection of newspaper clippings, magazine articles, photos, comics, surveys, and more all regarding Cannabis and it’s accompanying culture. The majority of these serve to be informational or entertaining, all in all creating a complete collection. (HV5822 .M3 S86 1970. Marvin Tatum Collection of Contemporary Literature. Image by Petrina Jackson)

Cover of The Marijuana Convictionby Richard Bonnie and Charles Whitebread II, published by the University Press of Virginia, 1974. This book discusses the relationship that Cannabis and the United States have had throughout the country’s history. Inside is a report from NIMH (National Institute of Mental Health) which gives a full synopsis Cannabis and its use, including user stereotypes, side effects, genetic damage, addiction, the gateway theory, and criminal implications. (HV5822 .M3 B66. Image by Petrina Jackson)

***

Megan Strait, First-Year Student

Photograph of Megan Strait by Sanjay Suchak, 19 November 2013.

“Who’s Loony Now?”

The scandalous story of John (a.k.a Archie) Armstrong Chaloner’s false commitment to Bloomingdale, an insane asylum in New York, is a tumultuous tale. In 1893, Archie envisioned a textile mill town in North Carolina that he christened Roanoke Rapids. He drafted his siblings, especially his younger brother, Winty, to invest in the town. Winty, who was originally excited about the idea, felt that Archie’s spending was out of control. So, when Archie came forward with his self-proclaimed ability to tap into his unconscious (the “X-Faculty”), Winty took the opportunity to lure him to New York where he was unfairly tried, declared insane, and institutionalized.

After four years, Archie escaped from the asylum and returned to New York to press charges. Archie petitioned the Supreme Court, won the case and was awarded $30,000, however “the judge immediately halved the award.” The win was what was important to him—his family surrendered the property they’d taken from him, and he was more or less able to rebuild his life.

Portrait of J. A. Chaloner by Rufus Holsinger, 1918. Chaloner’s hair and position’s semblance to Napoleon is no coincidence—Chaloner believed that he bore a great likeness to Napoleon. He was a huge fan of the infamous ruler—paintings and busts of Napoleon were spread throughout his estate, and it was his image that Chaloner assumed when under the influence of the X-Faculty. (MSS 9862. Holsinger Studio Collection. Image by Digitization Services)

Letter from Mary Elizabeth Breen to Archie, 1901. Breen congratulates Archie on his escape from Bloomingdale. She says that she had a friend who was falsely committed to Bloomingdale as well. She also sends a four-leaf clover to wish his new book, The X-Faculty, which explained his self-proclaimed mental abilities, success. (MSS 38-394-e. Gift of George Worthington. Image by Petrina Jackson)

***

Amelia Garcia, First-Year Student

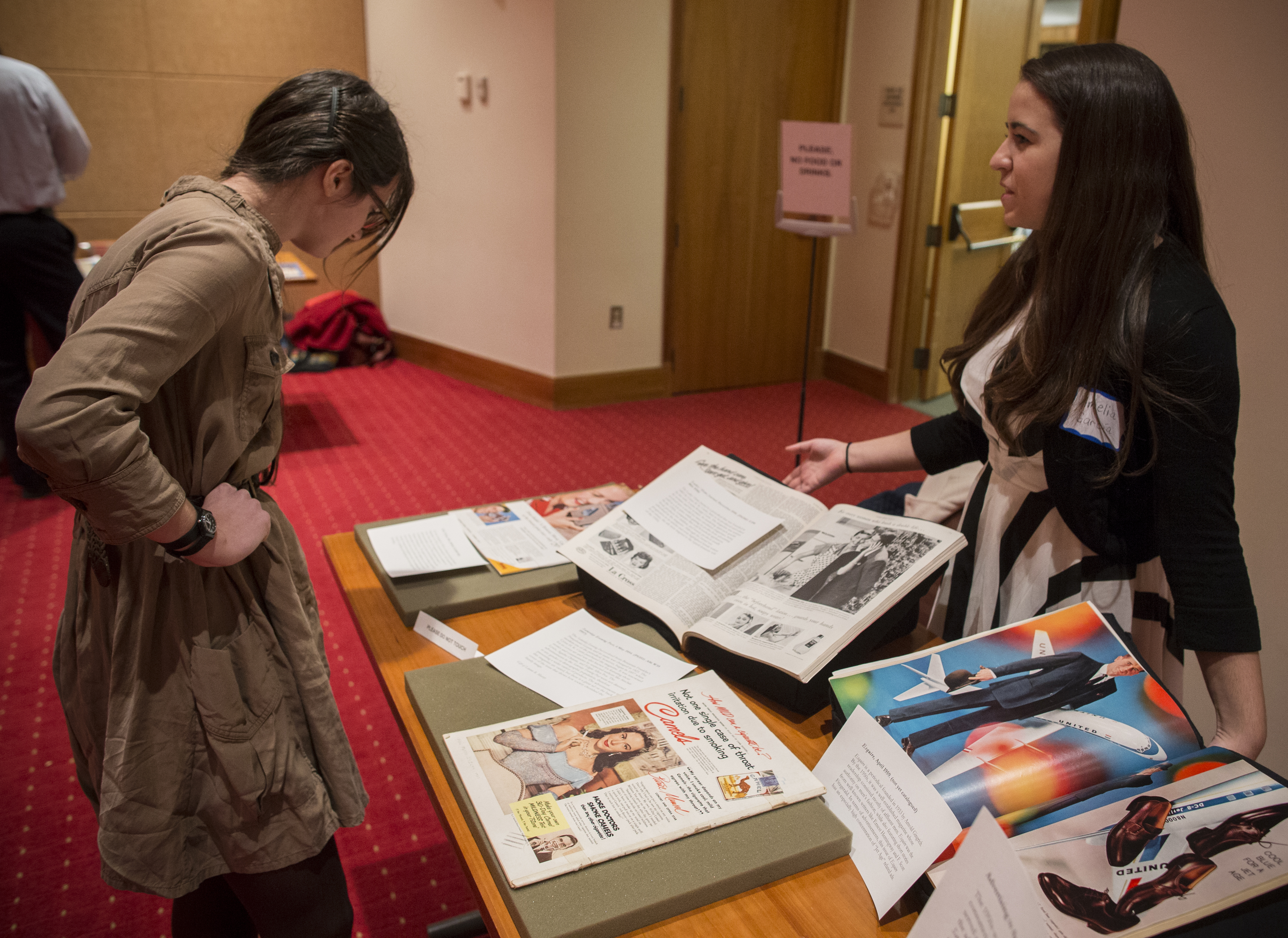

Amelia Garcia (right) talks to English graduate student and Special Collections employee about an advertisement from the 1950s, 19 November 2013. (Photograph by Sanjay Suchak)

Advertising to Americans: The 1950s

The 1950s was characterized as the decade of consumerism as the prosperous postwar economy served as a hotbed for advertisers. Upon analyzing the advertisements showcased in Esquire, The Saturday Evening Post, Life, and Ladies’ Home Journal, one can get a sense for how idealized life was like in the 50s. Overlapping themes in these periodicals’ ads include: wholesome family values, established women’s roles, smoking popularity, and a fascination with air travel.

Advertising during this period reflected a conscious return to traditional family values. The idea of a domesticated woman was also prevalent in 1950s advertising as most female-directed ads were for food, household appliances, beauty, or children’s products. During this time period, tobacco companies fought to yield the highest profit since smoking was cool, cheap, and socially acceptable. Americans were also mesmerized by commercial flying. Marketers capitalized on this to sell anything from shoes to club memberships, using the catchy term, the “Jet Age.”

Note: Students had the option of creating a digital story for Tales from Under Grounds, and Amelia, alone, chose it. Check out her amazing digital story on Advertising to Americans: The 1950s: